Violinist Shmuel Ashkenasi

and

Violist Richard Young

of the

Vermeer Quartet

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

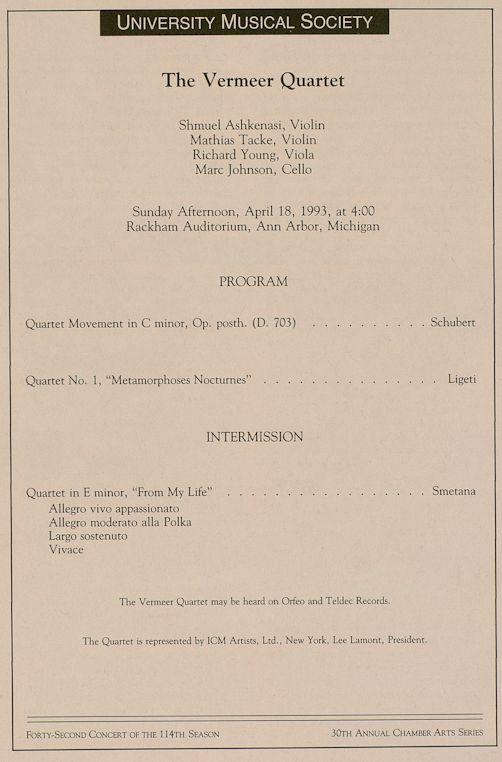

This is one of the few conversations I have had with more than one

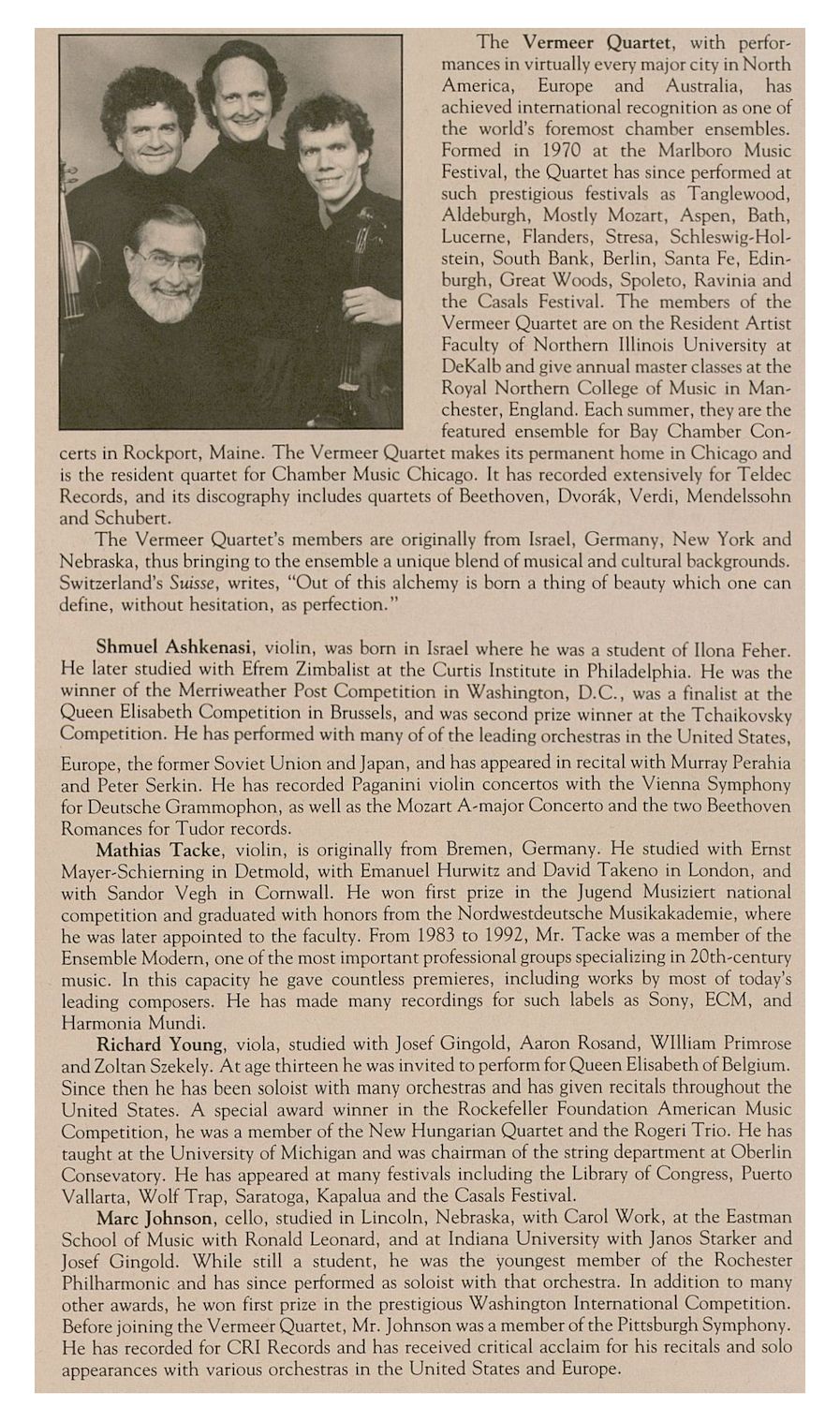

guest. Two members of the Vermeer Quartet, founder and first violinist

Shmuel Ashkenasi, and violist Richard Young, came to my home-studio in

June of 1989. Happily, it was a true conversation, with the ideas

flowing back and forth among all three of us. So rather than just

going back-and-forth, watch the indications of who is speaking.

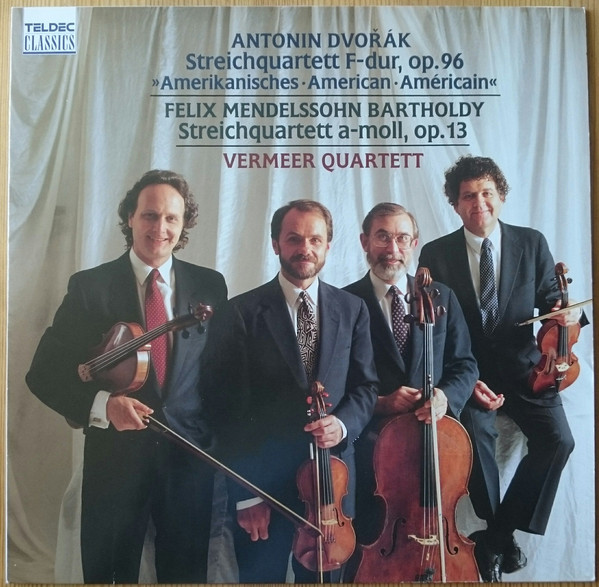

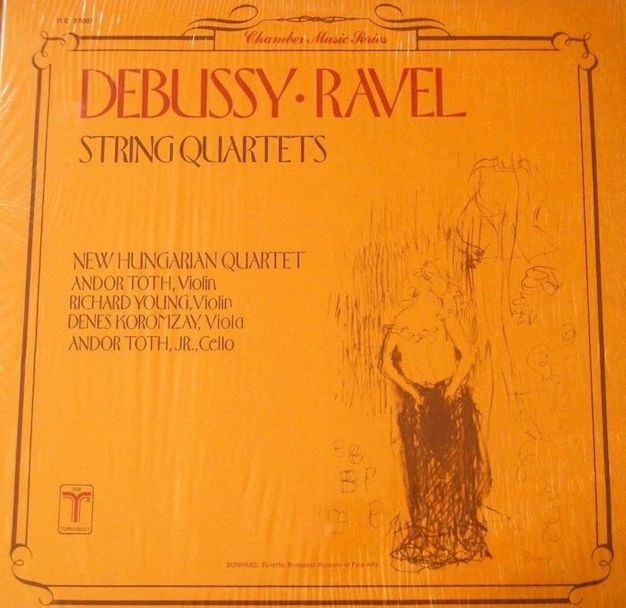

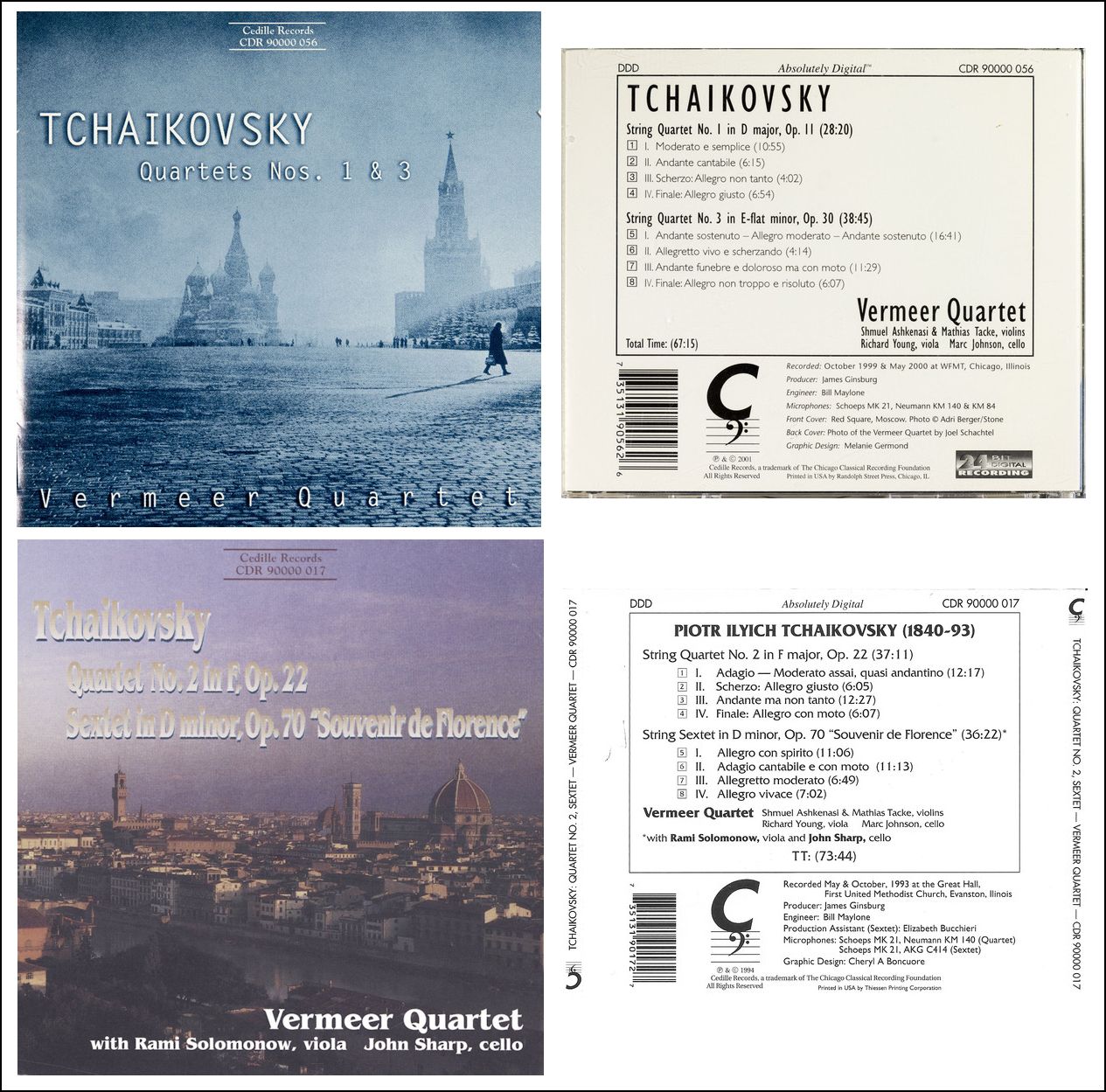

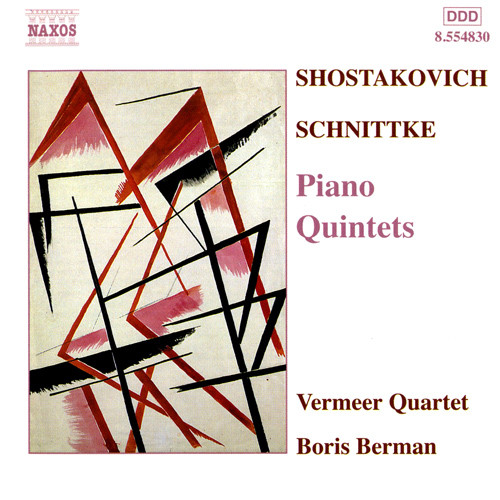

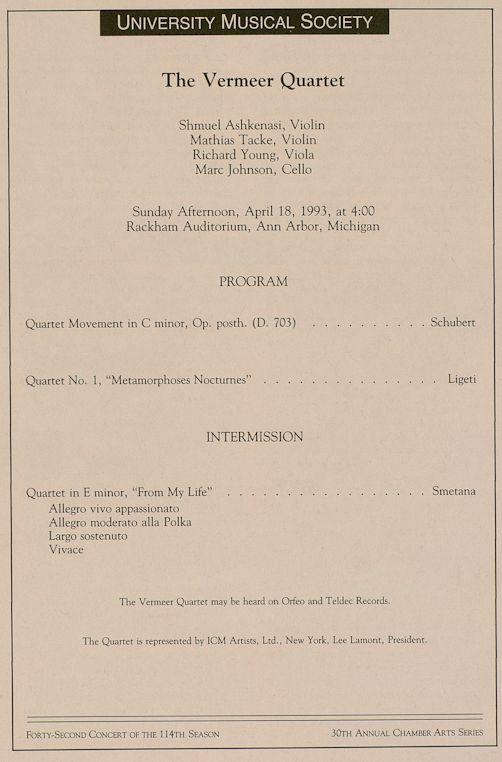

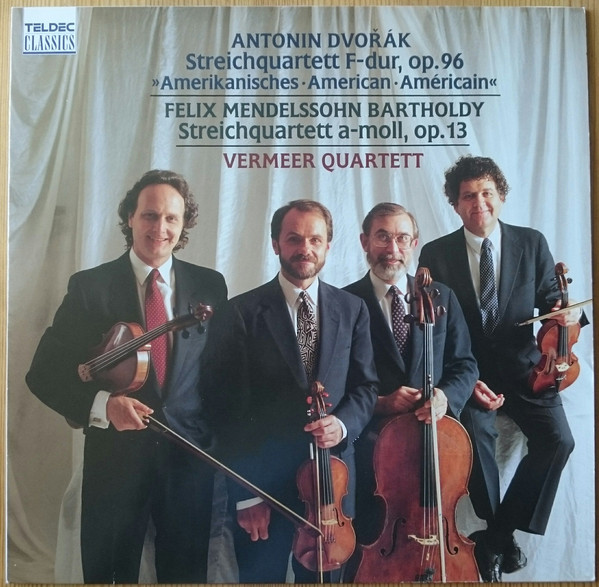

Note that the second violinist shown above, Mathias Tacke, joined

the ensemble in 1992, so the discussion on this webpage makes references

to Pierre Menard, who can be seen on the left in the LP cover-photo below.

Continuing toward the right in the photo are Shmuel, Richard, and Marc.

While setting up for the interview, the talk was about

the instruments, and specifically the technical needs of the bows . .

. . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: How often do bows have to

be re-haired?

Bruce Duffie: How often do bows have to

be re-haired?

Shmuel Ashkenasi: It depends on the

hair, and it depends on the player. If you use the same bow

all the time, probably just once a month, or once in six weeks. I

use more than one at a time, so I do it about every three months. I

have a whole bunch of bows.

Richard Young: We would change bows

between movements if it were possible.

BD: Why? What is it about the

hair that makes the sound different from one bow to another, or one

re-hairing to another?

Shmuel: Basically, the hair produces

the sound. It’s the fact that it is not slick. It is

coarse. If it is too coarse, the rosin will cake, and then it

will be too crunchy. If it’s too slick, then it doesn’t speak.

Then there is the strength of the hair.

BD: Do you specify a certain brand

of hair, or a certain thickness of hair, or hair from a certain animal?

Shmuel: No, it’s always horsetail,

and the best hair comes from Siberia and China. They all say

they have the best hair, and then you try it and it’s not good. Either

it breaks, or it doesn’t grip.

BD: Who does have the best hair?

Shmuel: I’ve had the best luck in Europe,

and Germany, and England. Occasionally, I have gotten some

pretty good hair here as well.

Richard: [Joking] I think the

real reason you got all those bows is because you have those instead

of mistresses.

BD: [With a wink] Is your violin

like your mistress?

Shmuel: [Smiles] No, it’s like

my wife. I’ve been faithful to that violin for close to twenty-five

years. Occasionally, I feel like having an affair, but I keep

coming back to the same violin.

BD: What is it about a particular violin,

or a particular viola, that makes it special in your hands, that

wouldn’t be as special in someone else’s hands and fingers?

Shmuel: It’s a combination of things.

A great violin could be special in many different hands, but

there are those violins that are not so great, that are special only

in certain hands. It depends how you treat it, how you play it,

the thickness of your fingers, the amount of pressure versus speed of

the bow, how close you are to the bridge, how much rosin you use... There

are so many factors.

BD: Then how much of that is the player,

and how much is the instrument?

Shmuel: It’s hard to say. I prefer

a great hall with a poor violin, to a terrible hall with a great violin.

BD: Do you feel the same thing on the

viola?

Richard: I think so, yes. The

important thing about the instrument is that whether it’s a famous

maker or not, the player just has to feel comfortable playing it. To

many people, just the response, the way the instrument responds to what

you try to do with it is almost more important than how it sounds, because

if you feel comfortable, if you feel the instruments responding, then you

play better, and sometimes you can overcome the limitations of an instrument

that may not be sounding so good.

BD: I assume, though, that to play

on an instrument day after day, you’ll get one that feels good and

sounds good as much as you can.

Richard: That’s the ideal.

BD: Are the old instruments

— Stradivarius, Amati, and all the other

famous names — usually better, or generally

better, or sometimes better?

Richard: Usually they are better.

Certainly, there are exceptions. We’ve all played Strads,

or Amatis, or Guarneri, the designer labels, some of which don’t sound

so good, but that’s really the exception rather than the rule. A

lot of times when I’ve played a big name instrument that I didn’t

care for so much, I would bet that in most cases I would like it better

if it were setup and adjusted more to my taste.

Richard: Usually they are better.

Certainly, there are exceptions. We’ve all played Strads,

or Amatis, or Guarneri, the designer labels, some of which don’t sound

so good, but that’s really the exception rather than the rule. A

lot of times when I’ve played a big name instrument that I didn’t

care for so much, I would bet that in most cases I would like it better

if it were setup and adjusted more to my taste.

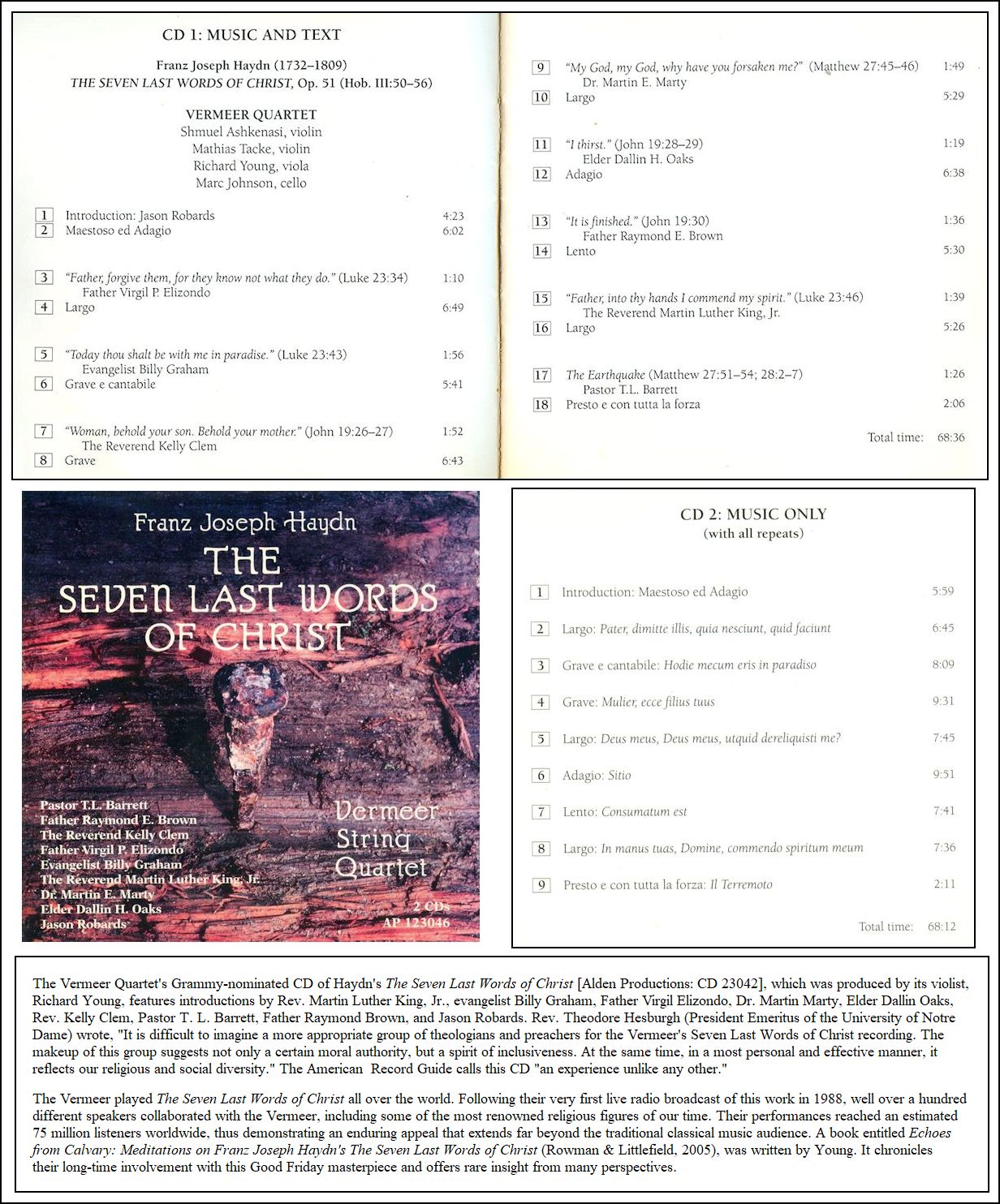

BD: Like moving the sound post around,

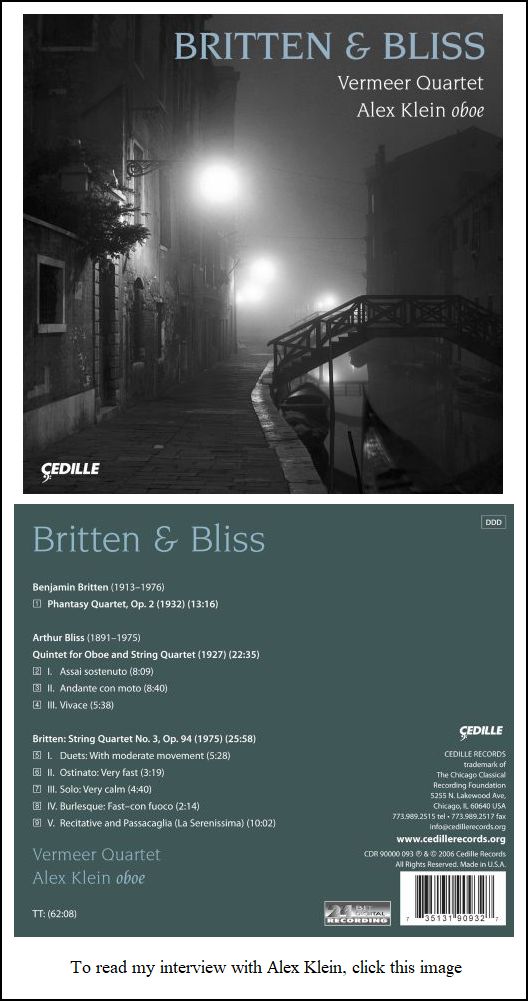

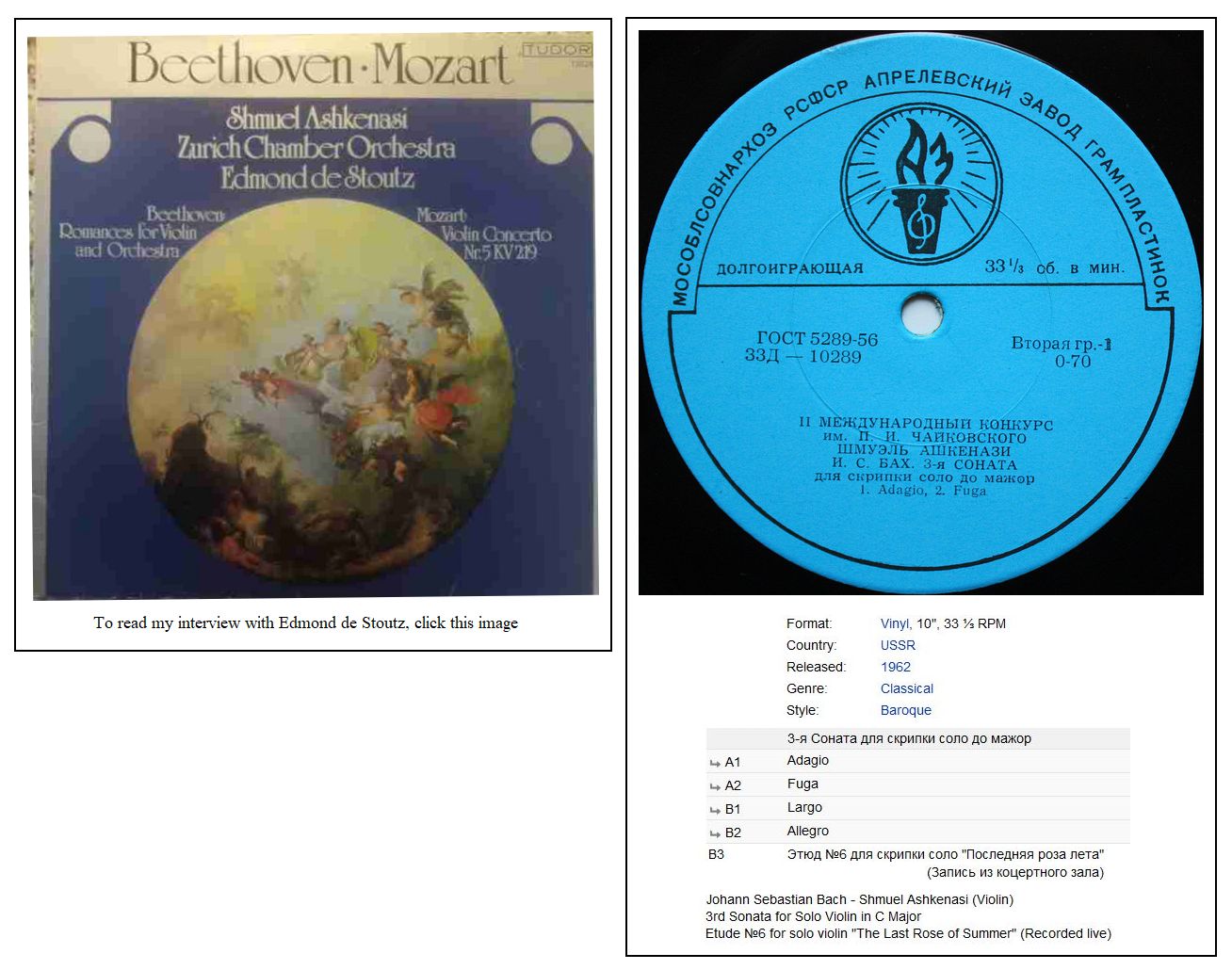

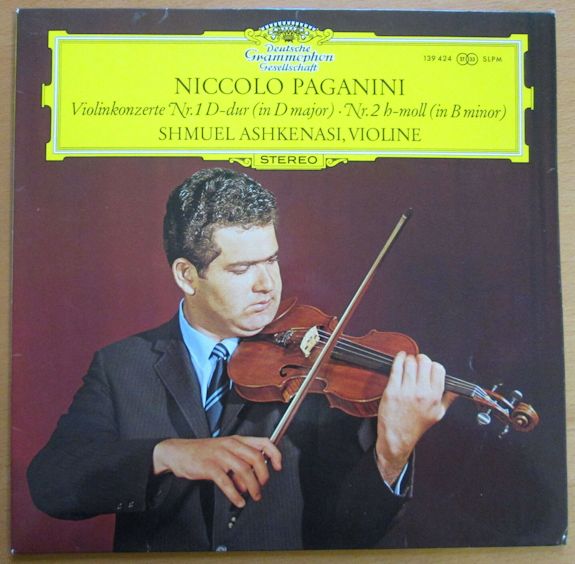

or something like that? [Note that the recording shown at

left has the Vienna Symphony Orchestra conducted by Heribert Esser.]

Richard: Move the sound post, make

the bridge higher or lower, use different strings, and so forth.

For example, the Zino Francescatti Strad. I saw it once

in a shop in New York, and it had an impossibly high bridge. I

don’t know very many people that could play an instrument with such

a high bridge. It means the strings are so much higher off the fingerboard,

so you have to press more.

BD: Then when you get way

up into the high positions, you’re having to press down very hard.

Richard: Yes, exactly. But he

was so used to it. It was his fiddle, and he just didn’t want

to change because, when you lower the bridge, it does change the response,

and also the quality of the sound. He just liked how it felt and

how it sounded, but it wouldn’t suit too many people.

BD: You two are members

of a quartet. Do you try to get instruments that will sound

best together as a quartet, or do you still try to have four individual

sounds?

Shmuel: We try for both. It depends

on the score. We each try to have an instrument that will blend

well, and have an individual characteristic at the same time. I

want to go back to the question you asked about the old instruments.

One point that deserves to be made, and what I find the most fascinating

and extremely interesting is the fact that those instruments which were

made 250 to 300 years ago were made for literature and halls that did

not demand a big sound. Nevertheless, they are chosen today even

for those characteristics. So, when you ask about all the Stradivariuses

and all the Amatis, I haven’t seen them all, but all that I’ve seen certainly

are superior instruments for the qualifications of the time. They

didn’t have big halls. They didn’t have the big romantic concertos.

They didn’t have the big orchestras, so they didn’t need really

a very big sound. They needed to find quality and evenness in their

sound, and they all have that. If they don’t, very often it is

because next to none of these instruments have been not tempered with.

A lot of wood has been taken off, and the neck has been modernized,

and they’ve been souped up to sound louder.

BD: And they have been put together

with new glue. I was led to believe at one time that they thought

it was the glue that Stradivarius used that made them special.

Shmuel: I don’t think that makes any

difference. If it makes a difference, it is such a small difference

that it couldn’t be audible.

BD: It’s not going to change the resonance?

Shmuel: I don’t believe so. I

may be wrong, but experiments have been done. If you press on

the ribs of the instrument, I don’t think it makes much difference.

BD: We’re talking about old instruments

playing old music, yet we’re still playing old music today in concert

halls large and small. Has the way that you produce music, basically

the same notes, changed for Twentieth century audiences, now as we head

into the Twenty-first century? You don’t

play Vivaldi for Vivaldi’s audience. Now, you’re playing Vivaldi

for a post-World War II audience, so it’s going to be a completely different

kind of thing. Do you play it differently because our ears are

different?

Richard: At the risk of sounding like

we don’t care about the audience — because

we do care a great deal — I don’t

think we play one bit differently for one audience or another because

it’s a modern audience as opposed to a different taste of back then.

We try to play what’s in the score, period. We try to bring

as much of ourselves as we can to bear on the music, whatever music it

is that we play. But the overwhelming governing factor that imbues

all of our work is what’s in the score. The same stuff is in the

score now as it was in Beethoven’s time, notwithstanding all the new

editions that we have.

Shmuel: I will say that there is an influence on the

audience that is sort of back-door, and that is, unfortunately, the

influence of the recording industry. The recording industry caters

to the audience, and that process changes tastes

— sometimes to the good, often to the bad.

Shmuel: I will say that there is an influence on the

audience that is sort of back-door, and that is, unfortunately, the

influence of the recording industry. The recording industry caters

to the audience, and that process changes tastes

— sometimes to the good, often to the bad.

BD: Does the audience influence the

choice of repertoire?

Shmuel: Yes, also.

BD: As the Vermeer Quartet, which of

you decides, or is it the four of you collectively that decides what

will go on each concert, or on each recording?

Shmuel: We do it always together. In

fact, we may be unique in that we have an unwritten rule in this group

that we will not play a work that all four of us don’t love.

BD: Each man has a veto?

Shmuel: Yes.

Richard: No majority rules in our quartet.

BD: It’s all or nothing.

Richard: That’s right.

Shmuel: Unfortunately, for other groups

such as string trios, they cannot have this because they don’t have

any repertoire because it’s so limited. Fortunately for us,

there are so many great masterpieces that we all love, that we never

run out of works that we all will agree to play.

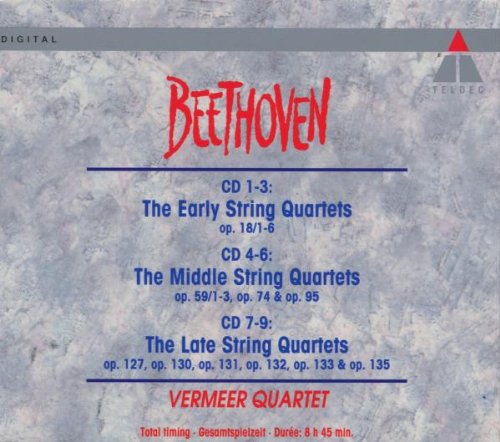

Richard: We are influenced by the audience,

but certainly by the auspices that we play for. We have to play

a large portion of the repertoire that’s the meat-and-potatoes of

the repertoire, only because the presenting societies demand it. That’s

how they sell their series, and they expect it. Most of our work

that we offer on tour centers around the masterpieces of Beethoven,

Mozart, Schubert, Schumann, and so forth. But we try always to

sneak some other things in there, and always something from the 20th century.

It is not necessarily brand-new — although

we have played some brand-new things — but

we try to stretch the ears a little bit here and there. It’s

good for us, too.

BD: Do you feel that each concert should

be an enjoying experience as well as a learning experience?

Shmuel: Absolutely.

BD: Then where should be the balance,

in either a piece of music or in the whole concert, between the artistic

achievement and entertainment value?

Shmuel: I don’t know that I would call

it an ‘entertainment value’

necessarily. One can enjoy it without it being entertaining.

One can be very moved and enjoy it that way. If it is a

very sad piece, you can enjoy it, and it’s not entertaining as such.

BD: Enjoy the sadness?

Shmuel: Enjoy the sadness, but ‘entertainment’

suggests that it must be always fun, or joyous, or even comic.

BD: Or frivolous?

Shmuel: Or frivolous, yes. Of

course, there is that element in music as well, but I don’t think

we would play a work that is offbeat or unknown just for its own sake.

Usually, we try to resurrect neglected works, or discover works

that are just not known, and are too good to be neglected.

Shmuel: Or frivolous, yes. Of

course, there is that element in music as well, but I don’t think

we would play a work that is offbeat or unknown just for its own sake.

Usually, we try to resurrect neglected works, or discover works

that are just not known, and are too good to be neglected.

Richard: Very often, we get advice from

loyal sponsors. There’s one man in particular that has been

very loyal to the quartet in Germany, who suggested we learn the first

Ligeti quartet. I’m quite sure we would not have learned it otherwise.

We trusted him, and trusted his judgment, and it turned out to

be just a dynamite piece. We carried it all year long, and it was

a real good experience. It was very successful as far as the

audiences were concerned.

BD: Since you carried it for a season,

is it likely to come back in another season?

Richard: Yes.

Shmuel: Yes.

BD: Does your experience with the first

quartet make you curious to want to learn the second quartet?

Shmuel: Very much so, but we will listen

to it. As a group, we are a distance away from learning it.

We may, and we may not. We have to convince each other that

it’s worthwhile.

Richard: Right now, we’re deciding

on the programs for the season after next. There’s a Max Bruch

quartet... he did write something other than the G Minor Concerto

and the Scottish Fantasy! There are actually three quartets.

BD: When someone says to take a look at

this or take a listen to that, what is it that you’re listening for?

What is it that’s going to decide “yes, we’ll do it,” or “no,

we won’t do it”?

Shmuel: There must be an immediate

appeal, especially if it’s a work that is more than forty or fifty

years old. It must have some originality. It must say something

new, or it must be an old thing in a new way, or in a marvelous way, or

in a moving way. It has to have value. You have to be seduced

by the music.

Richard: Next season, we’re playing a

quartet of Jacques Ibert. I don’t know of another quartet that’s

playing it. Pierre, our second violinist, heard the recording

on some offbeat label, and took a liking to it.

Shmuel: We all listened to it, not

from the beginning to the end, but to a bit of each movement just

to see that there’s no boring slow movement, or a trivial section. Then

we decided to chance it.

BD: Is the Vermeer quartet in a position

that it can play such a French piece in a French way, or do you just

play it in a musical way?

Shmuel: I don’t know what ‘French

way’ means.

Richard: [With a smile] We do

have a French Canadian in our group. Does that count? [Laughter

all around] It’s close.

Shmuel: We try to interpret the music

to its originality, and since it is French, it becomes part of the

French culture. Hopefully, it will sound to French people like

we play it in a French way, but I don’t know exactly what that means.

The music says it’s better.

BD: [Gently protesting] But you

wouldn’t play it and approach it the same way as some of the Beethoven

quartets.

Shmuel: We would approach it the same

way, but something else will come out. We also approach the

Beethoven quartets different one from the other, but I understand what

you’re saying. There is a Germanic approach, and certainly Italian

music should be played differently. But the music says that, and

hopefully we pick it out. We don’t play different works the same

way.

BD: Is that the individual genius of

Ibert and Beethoven?

Shmuel: I would imagine so, but the

individual genius was also influenced by the culture and heritage.

It comes back to nationality, and geography, and climate, and

culture.

Richard: There is such a thing as a stereotypical

French string sound. I guess that stereotype would suggest that

you play over the fingerboard, or you use wispy pastel colors, but

that, too, can become its own stereotype. It can become a cliché

if you just superimpose it over every bit of French music that you

approach. You really have to take each movement, each phrase,

each bar on its own merits and find the right sound, whether it’s a piece

of French music, or German music, or whatever.

BD: [With a wink] You don’t picture

a Parisian cafe, as opposed to a German beer hall?

Richard: [Smiles] Sometimes it

does help. There’s a use for literal images. If I’m having

trouble finding out what the music means, not often, but sometimes

it does help to try to put yourself in another frame of reference.

* * *

* *

BD: Have you, as a quartet, commissioned

new works?

Shmuel: We were involved in the commission of a

quartet of Ezra Laderman,

but we were not the only quartet involved. It was his Fifth

Quartet, and a few quartets were involved in the commission and

performing. The idea was that it shouldn’t be performed just once

or twice, but it should be performed all over the country simultaneously.

Shmuel: We were involved in the commission of a

quartet of Ezra Laderman,

but we were not the only quartet involved. It was his Fifth

Quartet, and a few quartets were involved in the commission and

performing. The idea was that it shouldn’t be performed just once

or twice, but it should be performed all over the country simultaneously.

Richard: We’ve also been involved in

performances that of works which were commissioned for us by other

presenting organizations. For example, Chamber Music Chicago

commissioned the Sextet [for Clarinet, Piano, and String Quartet]

of Dick Hyman (in 1988), and next season, there’s going to be a work

by Steven Mackey [On All Fours, premiered May 16, 1990] that’s

being commissioned for us to play.

BD: For these works, you’re presented

with a piece that you have to play?

Shmuel: Yes, and often it’s a problem.

This would be very much the exception to our rule, but if too

many arms are twisted, we will yield occasionally. It has to

be for a good cause, so even if we grow to hate the work, at least

we know that it’s in a good cause, like encouraging young composers. The

benefits often will justify us having to do the work.

BD: What advice would you have for

a composer who was writing a quartet or a chamber work for you?

Shmuel: For me, the first thing I would

say is that it should be written for what I was trained to do.

BD: That is to play beautiful sounds?

Shmuel: Not necessarily beautiful.

There is beauty in ugliness too, but literal demands and instrumental

demands that I was not trained to do make me feel incompetent....

like speaking, or singing, or shouting...

Richard: ...or hitting the back of

the instrument with your bow.

Shmuel: Yes. There are so many

effects. I’m not against finding new sounds, and I don’t think

that what we have is necessarily the ultimate, but I don’t feel qualified

to perform it unless I study it. The other thing is that it must

be alive. I don’t think that it should be difficult for its own

sake. Practically every new work that we’ve done was very difficult.

If it’s a great work, you justify the difficulty, but if it isn’t,

you feel that it’s difficult for its own sake, and that gets really cumbersome.

Richard: You don’t find how good the piece

is until you’ve invested so much time and effort. You’re delighted

when you find out that it’s worth all of that trouble, but more often

than not, for one reason or another, it’s not. I don’t want to

give the impression that I, or we, are not always looking for something

that’s original, something new, because the group wants to do new works.

But if you ask for advice, what we could tell other people who are

interested in writing new quartets is that not all composers, or not many

composers, really know all of the possibilities that even Beethoven explored.

They are writing without a full working knowledge of what’s possible

for a quartet, and instead they come up with new things or new techniques

that are sometimes valuable, sometimes not, but they don’t know the existing

vocabulary.

BD: Even in old masters, do you sometimes

feel that some of the composers are writing little symphonies rather

than great chamber works?

Shmuel: I personally don’t feel that there

is much difference. It’s only a difference of orchestration, but

it’s all chamber music — not in the

sense that amateurs get together and sight read, but in the sense that

there is an interplay between voices, and counterpoint. When I

play solo pieces of Bach, I find that is also chamber music, even though

I’m doing it alone. When I hear symphonies of Bruckner or Mahler,

these, too, are chamber music, in the sense of the interplay of voices.

It’s orchestrated differently, but I don’t find that Beethoven

piano sonatas and symphonies are all that much different.

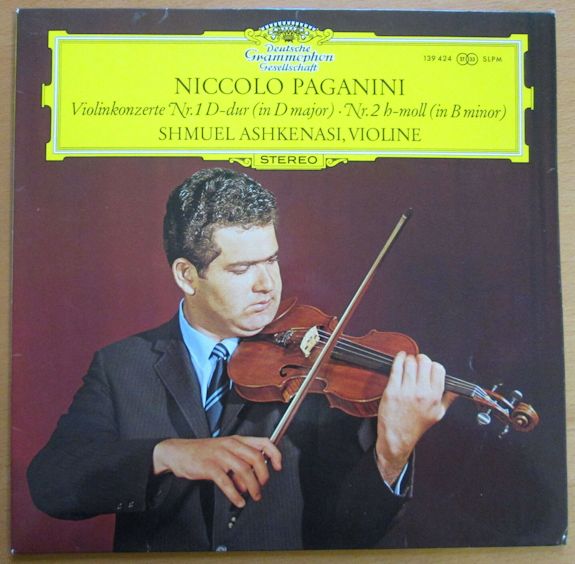

BD: Do you find a difference when you’re

playing a solo concerto in front of an orchestra, as opposed to four

men playing in the chamber group?

Shmuel: There is a difference, but it’s

in the form. It’s a Concerto Form, with the exposition repeated,

and that sort of thing. The quality of the music may be more showy,

such as an elaborate cadenza before the recapitulation at the end of the

movement. Many quartets do not have that, and many symphonies

also do not. Some do, but I don’t find that the content and the structure

of the music is all that much different. Indeed, Beethoven rewrote

works in certain combinations for other combinations presumably because

they would sell. He was considering that, as well.

BD: Are you conscious of the fact that

you want the Vermeer quartet to sell?

Shmuel: Yes.

Richard: We’re certainly made conscious

of that concept.

BD: Does that enter into the artistic

decisions?

Richard: Not at all.

Shmuel: Never.

Richard: We all know a lot of musicians

who were trained to do things that would project in such a way as

to make a popular impression, and we resist that.

* * *

* *

BD: Earlier we mentioned recordings. Do

you play differently in the recording studio than you do in the concert

hall?

Shmuel: Unfortunately, yes.

Shmuel: Unfortunately, yes.

Richard: Yes.

BD: How so?

Richard: [Quietly laughs] God,

there’s nothing harder to do than make a recording. We’ve all

been trained since we were very young to play for an audience, and

the reward, after all of the work, is to play it all the way through

in public. It’s a very festive occasion, and something that we

all are geared to do. But the recording situation is different,

and maybe it’s just because we haven’t all done it since we were ten

years old. It’s relatively new for us, but it’s a very unnatural

situation. I’m sure any artist would tell you this.

BD: There’s no truth to the idea that

you can just sit there and do it again, and again, and again until

you get it just the way you want you it?

Richard: When you play a passage and you

screw it up, you know that you have unlimited chances to go back and

do it again. But the more you go back and do little pieces of

things, subconsciously you become more safe in the way that you play,

and you become more self-conscious. As a result, you don’t play

as well... at least I don’t, and I think our quartet does not. Going

back, and back, and back, and nitpicking does not really help. Certainly

musically, but also technically, we probably play as well or better on the

stage than we do in the studio, even though we should know that in the

studio we can always go back and pick up the mistakes.

BD: In the studio, don’t you just simply

play it through?

Shmuel: We do.

Richard: We do. We try to, and

the producers know us by now. This is a common tendency, and

they force us to play things through, or play large portions of things,

even when one or more of us may say, “But what about three measures after

letter C? I missed something there.” But still, there’s just

that human element involved, and you know that the microphone is there

staring you in the face. You think that this is the one time you’ve

got to get it right. All your friends are going to hear this, and

regardless of who’s going to hear it, this is the one version that you’re

going to hear again.

BD: That’s different than knowing all

your friends are in the audience?

Richard: That’s right.

Shmuel: It’s actually a serious state of

affairs, which was caused, perhaps, by the recording industry. Because

the emphasis on technical competence — indeed

perfection — is so overwhelming,

that almost all the shadings, and more-important elements of a performance

are erased.

BD: Despite it all, have you basically

been pleased with the flat pieces of vinyl that have been issued?

Shmuel: Sometimes yes and sometimes no.

To begin with, there’s a compromise in the sound. There is only

so much that you can do in that particular studio, with that particular

microphone, with that particular set of equipment, and those particular

speakers. I’ve had the phenomenal experience of loving a recording

on a set of speakers and equipment, and hating the same recording on another

set. In fact, I found that it influenced the tempo, which obviously

remained the same.

BD: On one set it was too fast,

and on another one it was just right?

BD: On one set it was too fast,

and on another one it was just right?

Shmuel: That’s right. On one

it was very dry, and everything seemed slow.

BD: Is it not some comfort to know

that each individual, on his or her home stereo, is going to adjust

it to their liking?

Shmuel: Yes, it is of some comfort, but for

this whole generation there is an over-emphasis on technical perfection.

Mind you, I’m very much for playing perfectly, but not to the expense

of structurally being sound, and emotionally being one with the music.

That is not possible. You asked about doing it over, and over,

and over until you’re pleased. What you cannot do is do it the first

time. That is something that you cannot do the first or second time,

and by that later time, you’re spent. Moreover, you cannot record

the whole movement over and over. Logistically, it’s not possible.

So, you don’t have the structure in front of you. You have

to do little bits.

BD: You get good takes of the whole thing,

and then insert little patches?

Shmuel: That’s exactly what we do.

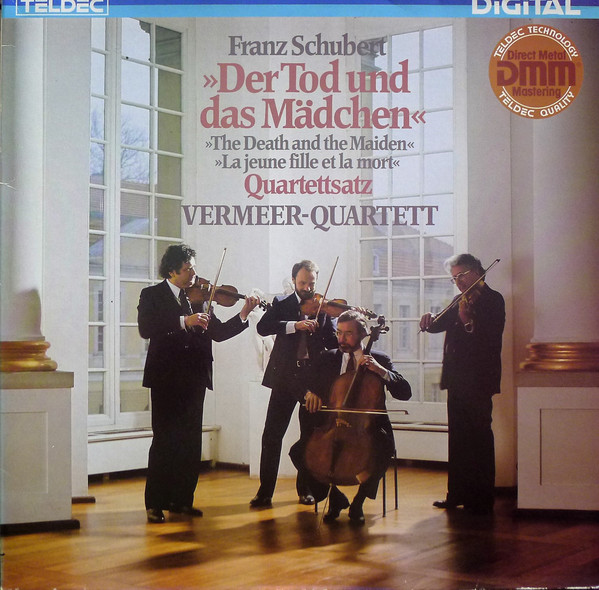

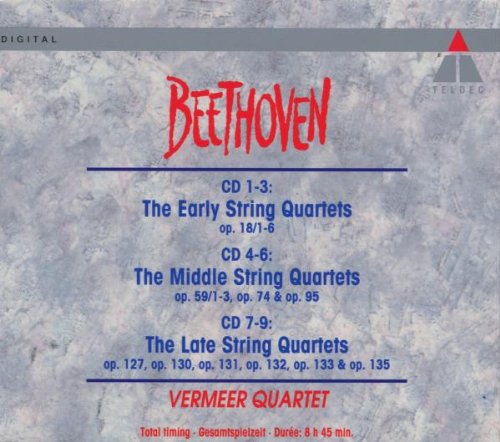

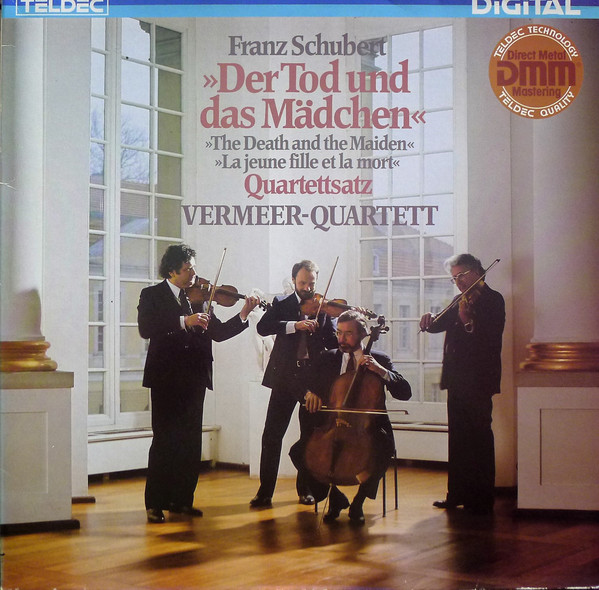

Richard: When we recorded the A

minor Quartet Op. 13 of Mendelssohn, we spent two or three days

in the Teldec studio in Berlin. It was just a coincidence, but

right after we finished that recording, we had been hired to play a radio

taping of the same piece across town in for German Radio. Of course,

the last thing we wanted to do after going through bloody hell with this

damn recording for Teldec, was to do the same piece the very next day.

When you record for the radio, they do some editing, but it’s minimal.

BD: Basically, they let it go unless

it falls apart?

Richard: Yes. It was an extraordinary

experience for me and for us. We went there after finishing the

recording, and I don’t think we ever played it better. They did

one minor insert, and that was it. We were just so relaxed. There

was something about having been told that previous day by that voice

of doom over the speaker (the producer in the booth) saying, “It is still

not together. Still out of tune.” So, for the radio there just

wasn’t anything that we didn’t know about existing problems, or tendencies

that we had in that piece that we couldn’t somehow account for.

BD: Would it have been good, then,

to go back across town once more and do it that way for Teldec?

Shmuel: There are too many variables.

The studio where we record doesn’t sound all that good to begin

with.

BD: [Surprised] Why do they put

up with that???

Shmuel: [Laughs] They own it.

It saves them money. There are so many factors. It

has to be relatively quiet, and not have airplanes, and subways, and

traffic, and that sort of thing. Also, it has to be good for recording

more things than just us. In some halls, it sounds well but it

doesn’t do so well on the recording. That radio studio sounded much

more flattering than the other one. But then, we did have the experience

of having rehearsed, and done all of the things, and even though I agree

with Richard that it felt awfully good, and it may well be the best

we ever played it, it wasn’t good enough for the recording.

Richard: I’d like to hear the tape

and compare it with the record. Of course, they wouldn’t have

let us leave the country if it wasn’t right. Earlier, when

you were talking about instruments, Shmuel mentioned how important is

the quality of the sound of the room itself, and the ambiance of the

room. I was told that the studio where we did the radio taping,

was the oldest recording studio for classical music in the world.

There was something about the sound of that room that was just so inspiring.

It was not any bigger than the studio that we had for Teldec. It

was about the size of a small high school gymnasium. It had high

ceilings, and a lot of wood just like the Teldec studio, but there’s

something about the character of the sound there that was special. It

put greater responsibility on the players to play well.

* * *

* *

BD: I asked before about advice to composers.

In all of this thinking about performing, what advice do you

have for young quartets, or even young individual players?

Shmuel: I have usually two paired answers.

The first one is to study the score. There is no substitute

for that, and it cannot be done enough. The other bit of advice

that I have is for the individual members. If they want to contribute

to their group, they should practice their parts. Those two elements

are the most important gifts that an individual can give to the quartet.

BD: Then once they come to the quartet, and

they are together as four players, what kind of advice do you have

— assuming they have prepared themselves individually?

Shmuel: They should love each other.

It’s easy to say and very difficult to do. In quartet

playing, the whole is the sum of the parts. It used to be that you

could hide one or two weaker members in a quartet

— the inner voices — but

today’s standards just don’t allow that. On any level, whether

it’s amateur, or student, or professional, the quartet is going to

be only as good as every member can play individually. Then you

come to grips with a host of ensemble problems, in working things and

balancing intonation within the group and so forth. But you’re

never going to play one chord in tune as a quartet if you can’t play in

tune yourself on your own instrument.

Shmuel: They should love each other.

It’s easy to say and very difficult to do. In quartet

playing, the whole is the sum of the parts. It used to be that you

could hide one or two weaker members in a quartet

— the inner voices — but

today’s standards just don’t allow that. On any level, whether

it’s amateur, or student, or professional, the quartet is going to

be only as good as every member can play individually. Then you

come to grips with a host of ensemble problems, in working things and

balancing intonation within the group and so forth. But you’re

never going to play one chord in tune as a quartet if you can’t play in

tune yourself on your own instrument.

BD: But then you have to come

together and make sure that all four will blend.

Shmuel: Yes.

Richard: When we consider technical

things in our quartet, we work the most on intonation, and voicing,

and balancing of chords.

BD: Who listens for that

— the individual members, or is there a fifth

set of ears?

Richard: It’s just the four of us.

We’d all like to think that we are able to separate ourselves

from our menial parts, and listen objectively as if from the outside.

Very often, when we listen to tapes or recordings, we can be a little

more objective because we’re not also playing our instruments and parts.

We have to train ourselves to listen not only to our part, and to

how that part sounds within the group, but also how it would sound from

outside the group.

BD: Is there ever a case

where the two violinists switch first and second?

Shmuel: Not in our group.

BD: Some groups do that.

Shmuel: That’s right.

Richard: The switching that is involved

is just with the different repertoire. For example, piano quartets

require only one violin, and usually Pierre has first refusal on the

violin part.

BD: [To Shmuel] You don’t feel

like you’re being forced out of work?

Shmuel: No! On the contrary,

I welcome him playing because, first of all, it gives me a break. I

have so many more notes as first violist of the quartet than anyone

else, so I’m delighted not to have to practice more. It’s very

healthy for the second violinist to play as much as possible, because

it gives him leadership and assertiveness qualities to sharpen, which

are very, very important.

BD: But that still isn’t enough to

influence you to play half the concert as first, and half the concert

as second?

Shmuel: No. I am not opposed

to that. I just think that it is not ultimately for the good

of the quartet. You may have the best first violinist and the

best second violinist in the world in a group, but if you switch them,

they may not be the best any more. But it’s possible. There

are very successful quartets who are switching, and certainly psychologically

and logistically it may have a lot of benefits.

Richard: At least in the case of a

couple quarters I can think of, it really does help keep peace in

the family, and that’s important. There’s this standard Second-Violin

Complex, that a person feels he’s not given the opportunities to shine

or project enough.

BD: [To Richard] You were a violinist,

and you switched over to viola. Has playing the inner voice meant

a big change in your psychology?

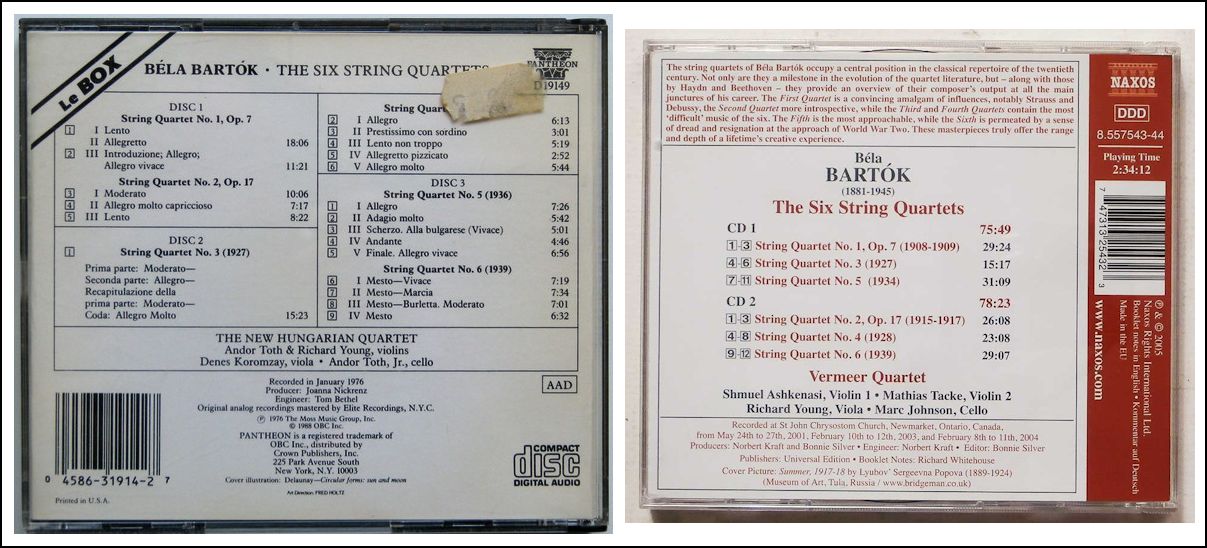

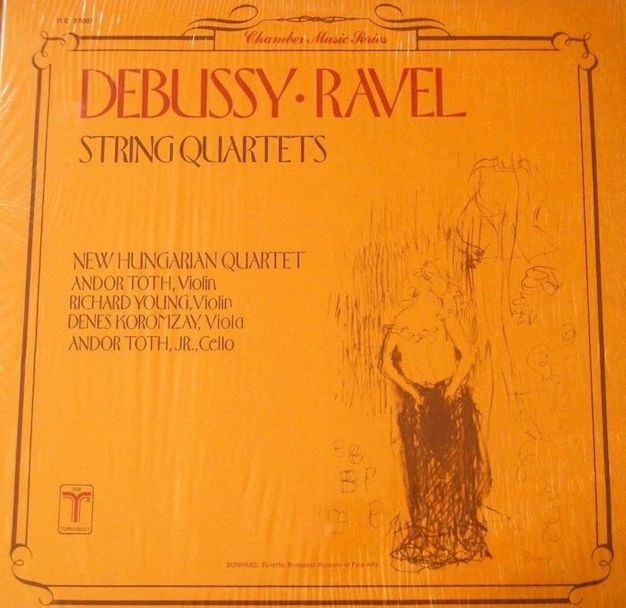

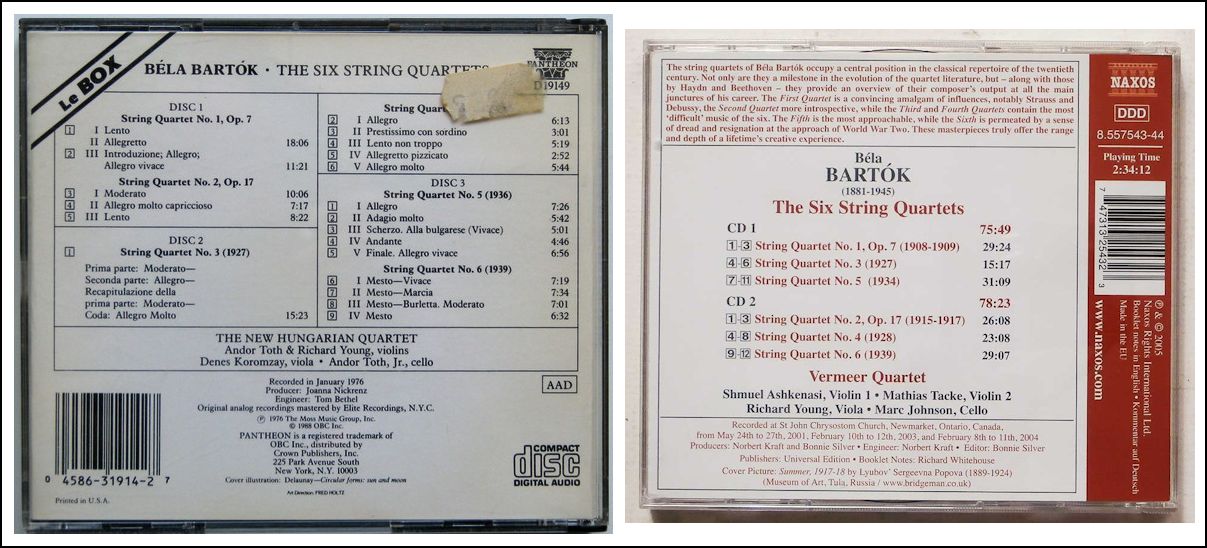

Richard: Actually, I played second

violin in the New Hungarian Quartet [LP shown above right, and CD shown

below], and I played violin in a piano trio. Now I’m playing

viola in this quartet, so I have had a taste of three of the roles in

a chamber group. [Laughing] Marc’s going to give me some

cello lessons... [More laughter]

BD: Is it really different playing

the inner voice as opposed to playing the first violin?

Richard: This is going to sound like

a flip answer, but it’s really the truth. One of the things that

was most disorienting for me when I first started playing viola in this

quartet, was simply walking to the other side of the stage to sit down,

and having the audience be on the wrong side of me. I’d

never played viola before. All my life, I had been used to walking

out and sitting or standing in a certain place in relation to the audience.

They were always off to my right, at about the 2 o’clock position.

There’s something just so confusing about walking out to the wrong

place, facing the wrong direction, and still having to feel comfortable

with it.

BD: Both of the violinists have their sound

going out toward the audience. For the violist, if anything,

the sound is going up into the rest of the quartet, or into the wings.

Can you change the position of the instrument at all?

Richard: To be honest with you, I’m

still not real comfortable. It seems that whatever I do, however

I sit, it’s either unnatural, or I’m just not sure how much it does

even matter. A lot of violists turn way out like that when they

duck. They dip the instrument so that the sound will come out through

the top towards the audience more. I’ve tried various things, and

it’s really difficult to know if anything is important.

Richard: To be honest with you, I’m

still not real comfortable. It seems that whatever I do, however

I sit, it’s either unnatural, or I’m just not sure how much it does

even matter. A lot of violists turn way out like that when they

duck. They dip the instrument so that the sound will come out through

the top towards the audience more. I’ve tried various things, and

it’s really difficult to know if anything is important.

BD: Do you then play very slightly

louder to compensate?

Richard: It depends who you ask. I

don’t do it intentionally, or at least not

for that reason.

BD: I assume this would all come

back to the question of balance. If your balance is not good,

then you’ve got to stress it just a little bit more to get out, to

be heard.

Richard: That’s right. The quartet that

had the ideal seating was the Kolisch Quartet. Usually, you

hold the violin with the left hand, and bow it with the right hand.

Because of an injury, he switched, and held it with the right

hand, and bowed with the left hand. What this meant was that

he was able to sit on the right, where the violist usually sits, and

the second violinist was where the first violinist usually is. So,

the two violinists were facing each other, and the violist was seated

where the second violinist usually is.

* * *

* *

BD: Let me get a little history of the Vermeer

Quartet. It was founded in Marlboro. Who were the original

members?

Shmuel: Before we were a quartet,

we looked for a second violinist for most of a whole year. We

played trios, and kept auditioning second violinists until we found Pierre.

In 1970, we became a quartet. I and Pierre were the

two violins, Scott Nikrenz was the violist, and Richard Sher was the

cellist. [Photo of this group is shown farther down on this webpage.]

Since then, we had one more cellist before Marc, who joined us about

five years into the life of the quartet, and he stayed. We have had

quite a few violists, who seem to be an endangered species. [Richard

Young joined the quartet in 1985, and remained through its final concerts

in 2007. LP cover at right shows violist Bernard Zaslav.]

BD: Why is it that violists are an

endangered species in a string quartet?

Shmuel: It’s

not only in string quartets. There just are not so many wonderful

violists around. There are some, but not as many as there are quartets.

Nobuko Imai, who used to be in the quartet, has had

quite a substantial solo career. There is also Kim Kashkashian.

She’s a terrific chamber music player, and she recorded all the Hindemith

solo sonatas recently.

Richard: The best violist these

days is Pinchas Zukerman. Most of the better violists are

chamber music players. It really goes back to the early

training. First of all, I should preface what I’m going to say

by saying that I don’t believe, as others believe, that the standards

are lower for viola than are for violin or cello. I just think that

there are fewer violists who are at that higher standard than there are

violinists and cellists. If you go to any of the public-school music

programs, more often than not, the kids that are encouraged to play viola

are the kids who are not good violinists, or who are somehow physically

awkward, or gangly, or big. They instinctively give them the big

instrument. So, already you have this ‘ugly

duckling syndrome’.

BD: So, really, it’s not the violists

that are shortchanging the music, but it’s the whole system that

is shortchanging the viola.

Shmuel: That’s right. Also, you

have a very big problem with the repertoire. To play in a quartet,

or to play in a great orchestra are the two things that a violist can

strive for. There are no solo careers out there for a violist...

at least none that is within one’s reasonable expectations.

BD: There is Harold in Italy

of Berlioz, and the Walton Concerto. Those are the only two

that I can think of off-hand.

Richard: [With a smile] There

are three and a half concertos for viola, so even if the public demanded

to hear more viola concertos, the repertoire isn’t there.

While preparing this conversation for

posting in August of 2020, I asked Richard to clarify his jest, and in

an e-mail message he replied that there was the Walton Concerto

(which was written in 1929 at the suggestion of Sir Thomas Beecham, and

when it was rejected by Lionel Tertis, it was premiered by Paul Hindemith),

and the Bartók Concerto (of which the unfinished sketches

were completed by Tibor Serly; it was commissioned and premiered by William

Primrose, conducted by Antal Dorati in 1949),

as well as Der Schwanendreher of Hindemith (premiered in 1935 by

the composer), plus the Mozart Sinfonia Concertante for Violin and Viola

(which dates from 1779. The solo viola part is written in D major instead

of E-Flat major, and the instrument is tuned a semitone

sharper (scordatura technique), to give a more brilliant tone. This technique

is uncommon when performed on the modern viola and is used mostly in

performance on original instruments.)

Richard also said there are works by Telemann, Stamitz, Hoffmeister,

and their contemporaries, which are mostly played by students, as well

as a few contemporary pieces. However, he said that Harold in

Italy doesn’t

really count, unless you also say that Don Quixote of Richard Strauss

is a cello concerto!

|

BD: Have you thought of encouraging some composers

that you admire to write a viola concerto?

Richard: Me, personally? No.

My life is with the quartet. I do a little bit of playing

outside the quartet, both violin and viola, but I have my hands full

as it is. I learned the standard viola repertoire in order to

teach my students, but I’m not a frustrated viola soloist.

BD: Are you a frustrated violinist?

Richard: No, I play enough violin,

so that it’s like getting out on the road and taking a spin. Then

I come back for the nitty-gritty in the quartet.

BD: When you play violin and viola,

how long does it take to adjust to the size, and the positions, and

everything else?

Richard: I’ve played violin and viola

on the same program, so I’m well-practiced on both. It’s not a

problem to switch.

BD: Irving Ilmer told me that

George Perle wrote a

piece which calls for both instruments. [Irving Ilmer was violist

with the Fine Arts Quartet from 1952-63, and was my next-door neighbor

during that period! Interestingly, two other violists in the Fine

Arts Quartet, which was founded in 1946, were also members of the Vermeer

Quartet before Richard Young.]

Richard: That’s right. I heard Irving

play it, and it’s a good piece. I like George Perle. I

like his music, and played one of his solo violin sonatas, which I liked

that very much. But no, I haven’t played this piece.

BD: [To Shmuel] Have you done

any playing on viola or has it been all violin?

Shmuel: I have not done any playing

on the viola professionally. When doctors and lawyers ask me

to play chamber music, I make sure to play the viola.

BD: Why?

Shmuel: Because I’ve done all of these

parts playing first violin with great players, my colleagues.

Now, to play those great works with people who are not as competent

doesn’t do much for me right at this point.

BD: Is the viola part a little more

of a challenge to you, and does it put you a little closer to their level?

Shmuel: Yes, it does. I’m not

very well-practiced on the viola, and I don’t read the clef that well,

so I feel there is a little bit more closeness.

BD: What else do you do besides quartet

playing? I understand you play a mean game of tennis...

Shmuel: I don’t know if it’s mean.

[Laughs] It’s getting gentler and gentler all the time.

I play a lot, and I watch a lot. I love the game. I love

the sport. I like to play, and I like to watch.

BD: Should we try to get the people

who play and watch tennis to come to Vermeer Quartet concerts?

Shmuel: We should try to get any people

to our concerts.

Richard: There’s a whole region of people that

Shmuel knows through his tennis connections, and I wouldn’t be surprised

if some of them don’t even know that you’re a violinist. [Laughs]

They probably think you’re an accountant.

Shmuel: Most of them do know that I’m

a violinist...

Richard: ...but when the phone rings in

your house and they ask Sam, not Shmuel, then we know it’s a tennis

date.

Shmuel: That’s right. [Laughs]

BD: Do they come and support the concerts

at all?

Shmuel: Some of them do. I let them know,

and if they can, more often than not, they do come.

BD: Are the people who play tennis

after working a long day, or on their day off, conscious of the fact

that a quartet will spend hours and hours rehearsing before they spend

two hours playing a concert?

Shmuel: I’m not sure that they’re really

conscious of the fact. I tell them, and then they believe me,

but I am not sure that they are aware of it. In fact, I’m not

sure that many musicians who don’t do this regularly are aware of the

hours that it takes to get proficient at playing quartets.

One of the first photos of the Vermeer Quartet

One of the first photos of the Vermeer Quartet

BD: How many concerts does the quartet

give each season?

Richard: This last year, it was around

eighty.

BD: And how many days did you rehearse?

Shmuel: Gosh, I would say we rehearse

more than 300 days.

Richard: We rehearse every day. One

day a week we teach, so we don’t rehearse in order to teach.

Shmuel: Occasionally, we take a day

off in the week, and occasionally we take vacations. But other

than that, we rehearse.

Richard: When we’re on tour, we go to Europe

two or three times a year for two to three weeks at a time, and we

even rehearse on the road sometimes when we’re playing at night.

BD: Do you get enough rehearsal?

Richard: It’s never enough. We carry

these pieces all season, and they still don’t behave. There’s

always something to criticize. One of my favorite quotations is

from Jascha Heifetz, who said, “There’s no such thing as perfection,

because once you attain a certain standard, only then do you find out

that it’s not good enough.” Every quartet player’s motto is that

you think you’re making some progress, and then you realize that compared

to what the score deserves, it’s still unworthy.

BD: And yet you go out there and present

it to the world.

Richard: We do our best, and we work

very hard in order to be as well-prepared as we can. Especially

with our group, our interpretations are always evolving. We’re

always trying to find better ways, better sounds, better techniques. Maybe

we find a new insight here or there, but we don’t let things stagnate.

BD: Even if you could rehearse for

days, and weeks, and months for each individual concert, it wouldn’t

help?

Shmuel: There is a time when you get negative

dividends, because rehearsing a lot does affect the social inter-relation,

and that then creeps back into the playing. When you don’t get

along as well, you don’t play together as well. A fine balance

has to be found between adequate rehearsal time and over-rehearsing. When

you just don’t want to be there anymore because you’ve hashed it to death,

then it’s time to stop. The reason we don’t rehearse too much

on tour is because we have learned that it does more harm than good very

often.

BD: Do you always rehearse in the same

place?

Shmuel: Most of the time we are in

my apartment, and sometimes in Pierre’s apartment when it’s convenient.

BD: Is playing string quartets fun?

Shmuel: It’s fun at the highest level. I

can’t imagine anything that is more fun than being with music, and

I can’t imagine anything being more fun in music than string quartets.

So, it is fun, but it’s very costly at the same time.

Richard: I would answer it in the same way.

Maybe ‘fun’ isn’t

the right word. ‘Rewarding’

is more the word I would use, but you have to put up with a great deal

of things that are emotionally very costly. Imagine going to

what we do every day at least six days a week. Each of us goes to

a rehearsal, which is a meeting with colleagues who know our strengths

and take them for granted, and who know our shortcomings, so they go

for the jugular as far as that’s concerned. I know that when I go

to rehearsal I’m going to be criticized by a panel of experts. How

many people, when they go to work every day, are subjected to that kind

of thing? All of us feel that, and all of us feel the social pressure.

That is very much a part of any string quartet. It almost makes

playing for an audience child’s play, compared to the pressures that

every string quartet has to deal with just within the group.

Shmuel: That in itself also has its good side.

I haven’t had a violin lesson in over twenty-five years, but I

am getting an awful lot of them every day. I’m grateful for

three sets of ears not letting me get away with it if I’m playing out

of tune, or if I’m scratching. Some of the criticism is justified,

and some of it may be less justified, but be that as it may, it is very,

very good to know that I have these ears to keep me honest, and to see

that I maintain a standard.

BD: That makes you a better player?

Shmuel: It certainly does.

Richard: All of us collectively makes

the quartet better.

Shmuel: I would imagine that it must. Sometimes

we play for audiences that are really not quite worthy of the great

literature that we present. It’s not very often, but it happens.

But nevertheless, at least I know that in that audience are three

people that are worthy, and I’m playing with and for them. That

in itself, the quality of that part of the audience, maintains the standard

of integrity, and that is very rewarding. I don’t know many professional

people who can say that.

BD: Thank you for all of the music, both live and on

recordings.

Shmuel: Thank you.

Richard: Yes, thank you.

© 1989 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on June 21, 1989.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB two months later. This transcription

was made in 2020, and posted on this website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted

on this website, click here. To

read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print,

as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975

until its final moment as a classical

station in February of 2001. His interviews

have also appeared in various magazines and journals

since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series

on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You

are invited to visit his website for more information

about his work, including selected

transcripts of other interviews, plus

a full list

of his guests. He would also like to call your

attention to the photos and information about

his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

Bruce Duffie: How often do bows have to

be re-haired?

Bruce Duffie: How often do bows have to

be re-haired?  Richard: Usually they are better.

Certainly, there are exceptions. We’ve all played Strads,

or Amatis, or Guarneri, the designer labels, some of which don’t sound

so good, but that’s really the exception rather than the rule. A

lot of times when I’ve played a big name instrument that I didn’t

care for so much, I would bet that in most cases I would like it better

if it were setup and adjusted more to my taste.

Richard: Usually they are better.

Certainly, there are exceptions. We’ve all played Strads,

or Amatis, or Guarneri, the designer labels, some of which don’t sound

so good, but that’s really the exception rather than the rule. A

lot of times when I’ve played a big name instrument that I didn’t

care for so much, I would bet that in most cases I would like it better

if it were setup and adjusted more to my taste. Shmuel: I will say that there is an influence on the

audience that is sort of back-door, and that is, unfortunately, the

influence of the recording industry. The recording industry caters

to the audience, and that process changes tastes

— sometimes to the good, often to the bad.

Shmuel: I will say that there is an influence on the

audience that is sort of back-door, and that is, unfortunately, the

influence of the recording industry. The recording industry caters

to the audience, and that process changes tastes

— sometimes to the good, often to the bad. Shmuel: Or frivolous, yes. Of

course, there is that element in music as well, but I don’t think

we would play a work that is offbeat or unknown just for its own sake.

Usually, we try to resurrect neglected works, or discover works

that are just not known, and are too good to be neglected.

Shmuel: Or frivolous, yes. Of

course, there is that element in music as well, but I don’t think

we would play a work that is offbeat or unknown just for its own sake.

Usually, we try to resurrect neglected works, or discover works

that are just not known, and are too good to be neglected. Shmuel: We were involved in the commission of a

quartet of Ezra Laderman,

but we were not the only quartet involved. It was his Fifth

Quartet, and a few quartets were involved in the commission and

performing. The idea was that it shouldn’t be performed just once

or twice, but it should be performed all over the country simultaneously.

Shmuel: We were involved in the commission of a

quartet of Ezra Laderman,

but we were not the only quartet involved. It was his Fifth

Quartet, and a few quartets were involved in the commission and

performing. The idea was that it shouldn’t be performed just once

or twice, but it should be performed all over the country simultaneously. Shmuel: Unfortunately, yes.

Shmuel: Unfortunately, yes. BD: On one set it was too fast,

and on another one it was just right?

BD: On one set it was too fast,

and on another one it was just right? Shmuel: They should love each other.

It’s easy to say and very difficult to do. In quartet

playing, the whole is the sum of the parts. It used to be that you

could hide one or two weaker members in a quartet

— the inner voices — but

today’s standards just don’t allow that. On any level, whether

it’s amateur, or student, or professional, the quartet is going to

be only as good as every member can play individually. Then you

come to grips with a host of ensemble problems, in working things and

balancing intonation within the group and so forth. But you’re

never going to play one chord in tune as a quartet if you can’t play in

tune yourself on your own instrument.

Shmuel: They should love each other.

It’s easy to say and very difficult to do. In quartet

playing, the whole is the sum of the parts. It used to be that you

could hide one or two weaker members in a quartet

— the inner voices — but

today’s standards just don’t allow that. On any level, whether

it’s amateur, or student, or professional, the quartet is going to

be only as good as every member can play individually. Then you

come to grips with a host of ensemble problems, in working things and

balancing intonation within the group and so forth. But you’re

never going to play one chord in tune as a quartet if you can’t play in

tune yourself on your own instrument.

Richard: To be honest with you, I’m

still not real comfortable. It seems that whatever I do, however

I sit, it’s either unnatural, or I’m just not sure how much it does

even matter. A lot of violists turn way out like that when they

duck. They dip the instrument so that the sound will come out through

the top towards the audience more. I’ve tried various things, and

it’s really difficult to know if anything is important.

Richard: To be honest with you, I’m

still not real comfortable. It seems that whatever I do, however

I sit, it’s either unnatural, or I’m just not sure how much it does

even matter. A lot of violists turn way out like that when they

duck. They dip the instrument so that the sound will come out through

the top towards the audience more. I’ve tried various things, and

it’s really difficult to know if anything is important.