|

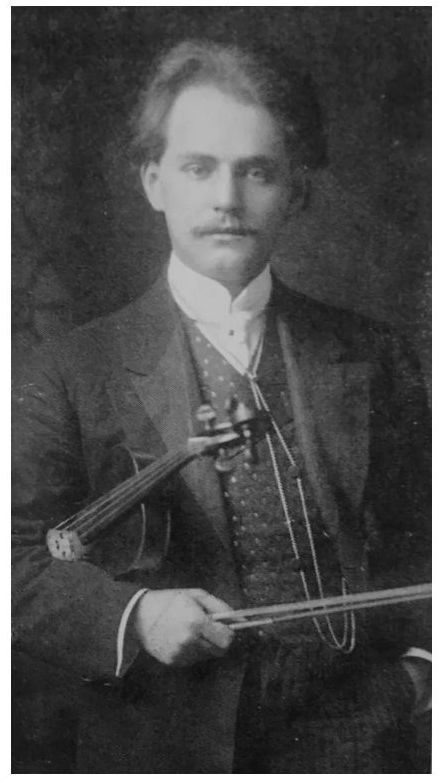

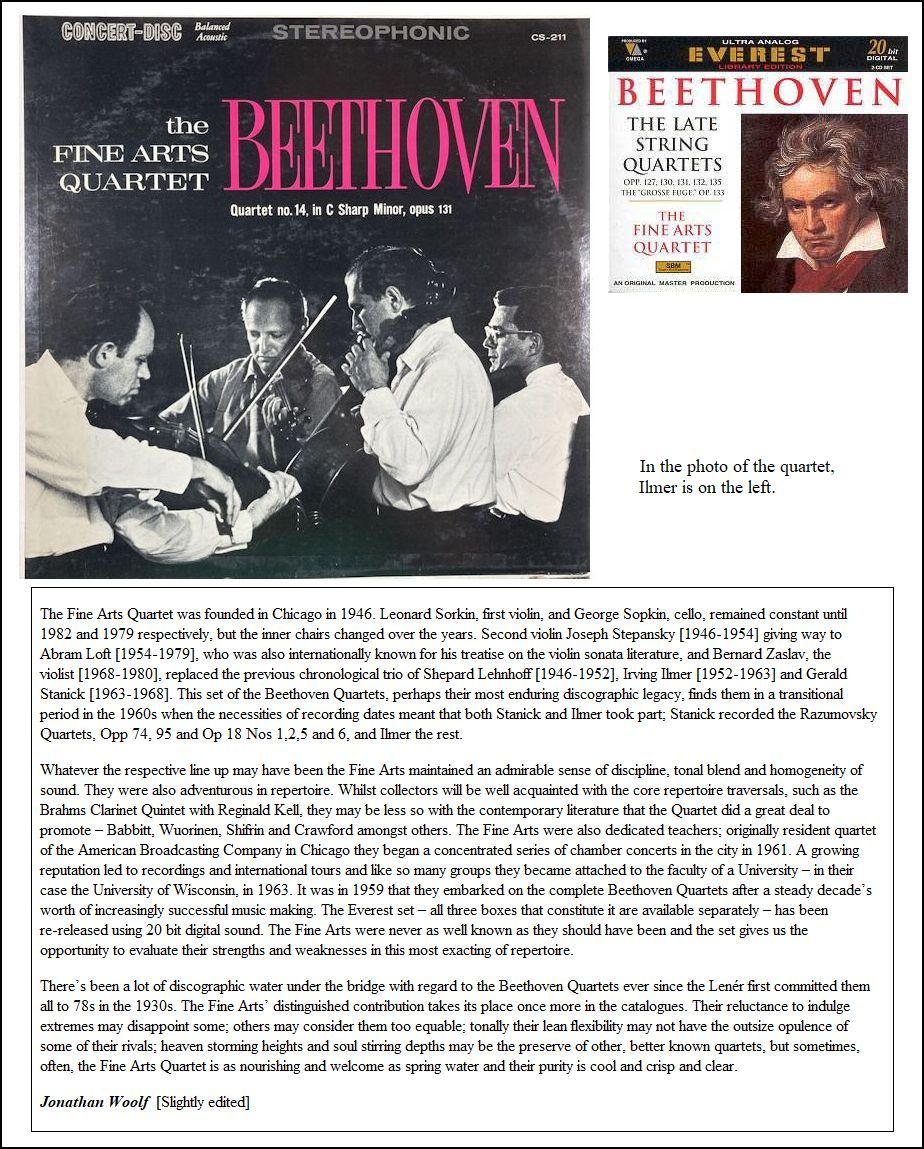

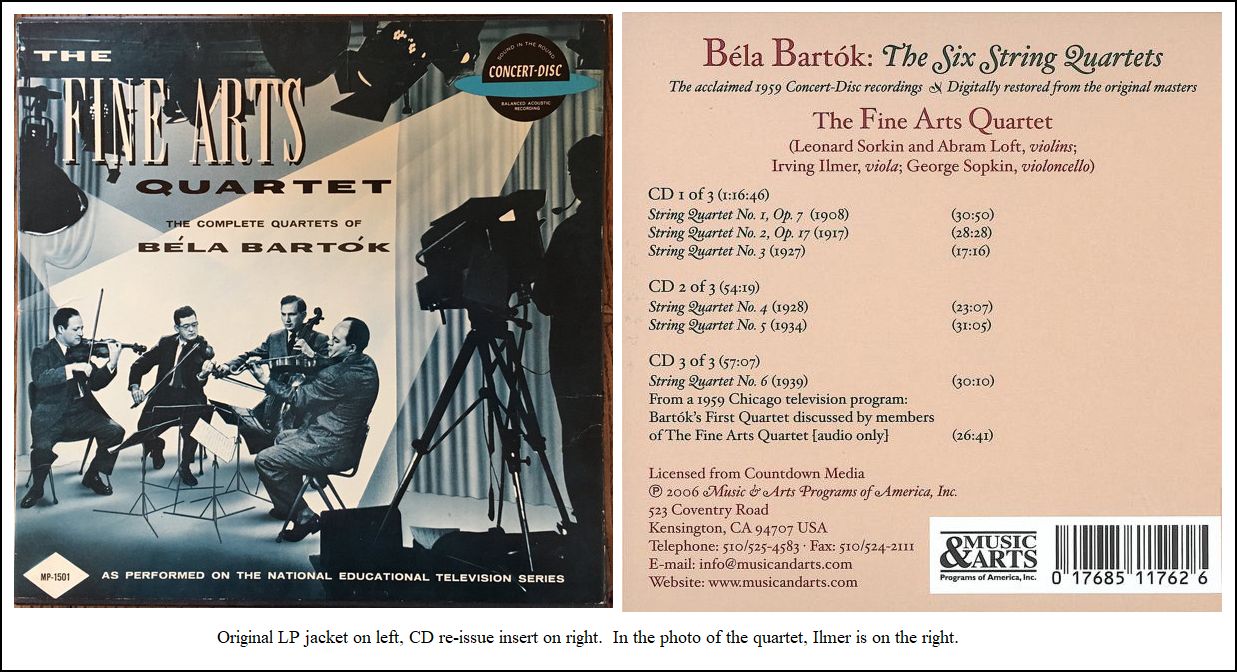

Born

September 13, 1919 in Vienna, Mr. Ilmer moved to Chicago's South Side

when he was in his teens. He made an early debut at the Civic Opera House

as an assistant artist with Metropolitan Opera star, Grace Moore. He was

a trombonist in the Army Air Corps band during World War II. Upon returning

to Chicago, Mr. Ilmer played violin with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

for six years. He subsequently performed with many ensembles, including

the Fine Arts Quartet, the Contemporary Chamber Players at the University

of Chicago, and the resident quartet of the Aspen Music Festival in Colorado.

While

still living in the Chicago area, he taught at the University of Wisconsin

at Milwaukee, Northwestern University, and the Cleveland Institute of

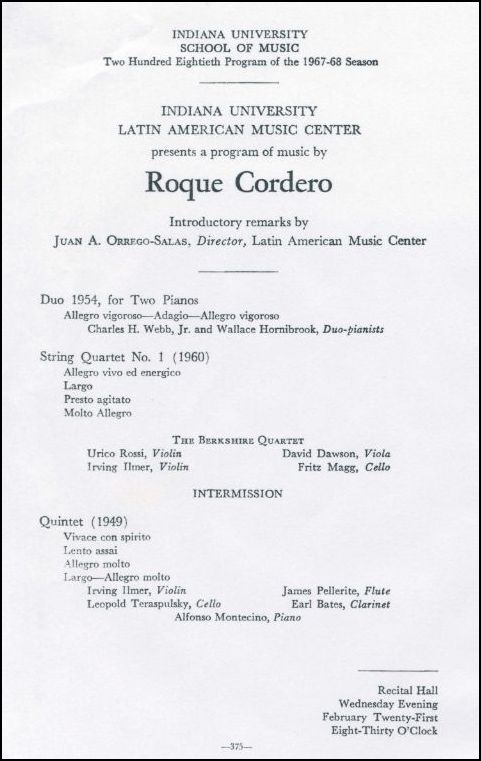

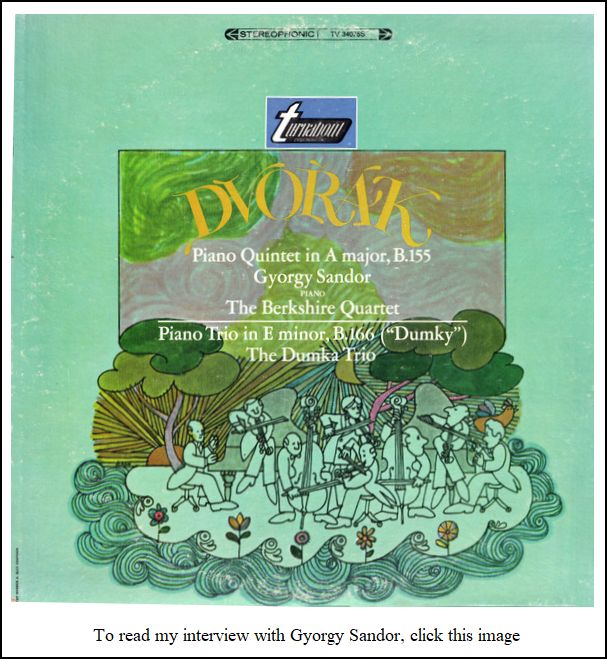

Music. Between 1964 and 1976, Mr. Ilmer was a faculty member at Indiana

University School of Music and the University of Kentucky. He then spent

11 years as concertmaster of the Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony Orchestra in

Ontario. Mr.

Ilmer moved back to Evanston in 1987 and performed with the Governors State

University string quartet and the Chicago String Ensemble. Survivors

include his wife, Janet K. Schenk; two sons, Steven and Paul; and three

grandchildren. A memorial service will be held at 2 p.m. Jan. 17 in the

Second Unitarian Church, 656 W. Barry Ave., Chicago.

|

Richard Rudolph Czerwonky (1886-1949) was a distinguished violinist,

composer and conductor of Polish-American ancestry. The majority of his

career was spent in Chicago where he became an influential figure in

the city’s classical music education and orchestra scene during the first

half of the twentieth century, especially during the 1930s and 1940s.

Richard Rudolph Czerwonky (1886-1949) was a distinguished violinist,

composer and conductor of Polish-American ancestry. The majority of his

career was spent in Chicago where he became an influential figure in

the city’s classical music education and orchestra scene during the first

half of the twentieth century, especially during the 1930s and 1940s.

Born in Birnbaum, Germany (present-day Międzychód, Poland) he was an accomplished violinist from an early age, having studied with the great Austro-Hungarian violinist, conductor and composer Joseph Joachim in his youth. After winning the Mendelssohn prize at age 18 and completing an extensive European tour, he was debuted with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in 1906. He moved to the United States to become assistant concertmaster of the Boston Symphony Orchestra later that year– a remarkable accomplishment at not yet 20 years of age. In 1909, Czerwonky left Boston to become concertmaster, assistant conductor and soloist with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra– a position he held for nine years when he moved to Chicago in 1918 to head the violin department and conduct the orchestra of the new Bush Conservatory of Music. He remained based in the Chicago area for the rest of his career, eventually joining the faculty of DePaul University’s School of Music and became head of the violin program in and conductor of the DePaul Symphony Orchestra. In 1927 he reorganized the Chicago Philharmonic Orchestra and conducted the ensemble for over twenty years– shepherding the organization through the Great Depression. While heading the Chicago Philharmonic, he developed their live WGN Chicago radio broadcasts and led a series of popular concerts in Grant Park. The Chicago Philharmonic was also featured in broadcasts airing on WMAQ and NBC, CBS, MBS and ABC stations during his tenure. He also conducted the Kenosha (Wisconsin) Symphony. Czerwonky was a promoter of women in classical music evidenced by several actions during his time in Chicago. He assisted in the founding of the Women’s Symphony Orchestra of Chicago in 1925 and served as conductor for their first season (1925-1926) before resigning once the orchestra was able to name Ethel Leginska (1886-1970) as the organization’s first female conductor. During Czerwonky’s tenure with the Chicago Philharmonic Orchestra, the organization claimed to be the first professional orchestra in Chicago to include both men and women in its ranks. Czerwonky was also known to feature the works of women in his concert programming as well as the works of local Chicago composers. In addition to his teaching and conducting, he continued to perform as a soloist and composed extensively for violin, piano and orchestra. He performed as a soloist on his own works or other compositions with many of the major orchestras in the United States and Germany in addition to his own Chicago Philharmonic and the Richard Czerwonky String Quartet. He was also frequently featured in performances broadcast on American and German radio. He was a member of ASCAP and had numerous works published by Carl Fischer and Oliver Ditson. Most of these published works are unfortunately now out-of-print and many are rare. |

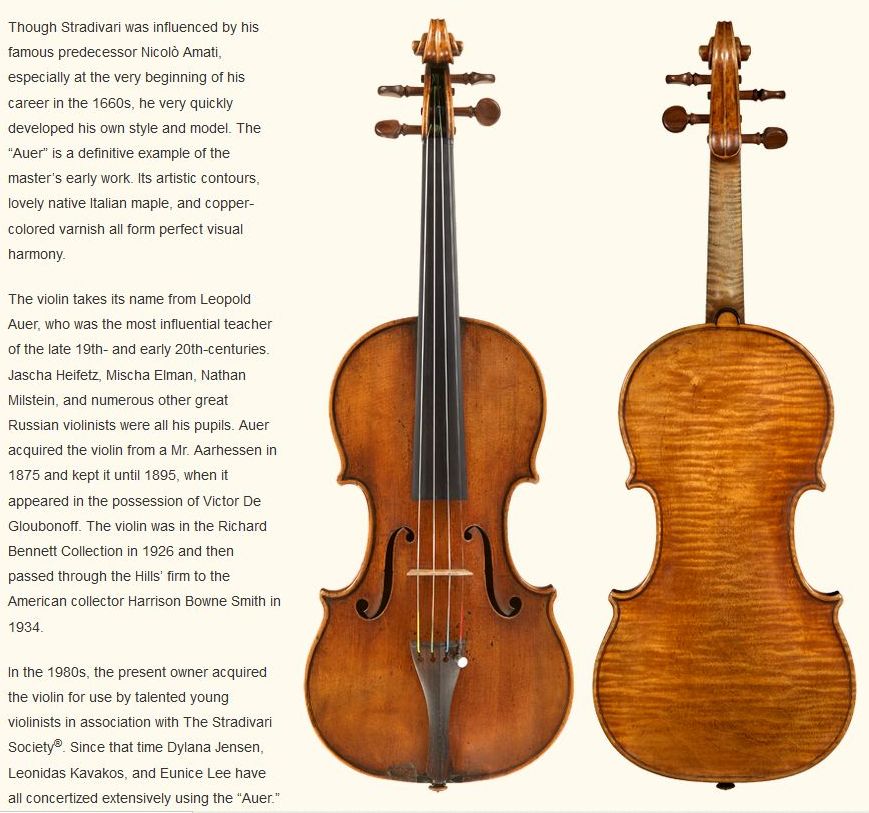

‘ex-Leopold Auer’ Stradivari, Cremona, 1690The stunning ‘flame’ patterns that we see on the back of fine instruments are an optical effect produced when the grain of maple grows in undulating patterns. When planed, scraped or burnished and particularly under certain types of varnish, the flame reflects light and appears to have an almost holographic effect. When one holds a heavily-flamed violin in strong sunlight, the figure can seem as if it’s alive and moving. The way in which maple is cut and prepared determines the flame’s appearance. The typical ‘tiger stripe’ flame pattern results when the tree is cut “on the quarter” which means a triangular wedge is cut with its apex at the center of the tree and its two long sides equal radii of the trunk. Alternatively, wood for a violin can be cut “on the slab” which means a section of the trunk is cut that is not a radius of the circle and doesn’t pass through the centre of the tree. The 1690 ‘ex-Leopold Auer’ Stradivari shows an excellent example of maple cut on the slab. The figure is iridescent and lively but slightly less pronounced and more mottled and irregular. Stradivari used slab-cut maple extensively in the 1680s and 90s as had the Amatis, Guarneris and Rugeris before him, but his instruments from the 18th century more typically use maple cut on the quarter. Commentary by Jason Price

|

|

Beautifully gowned, Grace Moore looked a picture as she appeared upon the Civic Opera House stage in her lone recital under the management of Harry Zelzer and charmed the vast auditory with her graciousness and vivacity, which, added to her lovely voice, made her song doubly enjoyable. Irving Ilmer performed several violin soli with authority and a luscious and crystalline tone. An artist student of Richard Czerwonky, Ilmer is forging ahead both technically and interpretatively. |

| Fritz Siegal was born in Vienna in 1917 to parents

of Russian and Czechoslovakian background. They immigrated to the United

States in 1922 and settled in Chicago. He attended Lane Technical High

School. Later, he served as concertmaster of Lyric Opera of Chicago

from the mid-1950s until 1966, Grant Park from 1945-1969, the Boston Pops,

and retired from the Pittsburgh Symphony at age seventy to teach violin,

having been concertmaster for 22 years beginning in 1967. Besides leading

the first violin section, he often served as assistant to the conductor. Partly his ability to serve in more than one orchestra was because Grant Park played only in the summer, and the Lyric and Pittsburgh seasons were at other times of the year. His first professional job was with the Illinois Symphony, and the Stevens College Symphony. He played with the Chicago Symphony on the Carnation Milk Radio Program, Percy Faith conducting, and became concertmaster for the Seattle Symphony in 1939. After the birth of two children he returned to Chicago to play for NBC Television Orchestra, and later with the Indianapolis Symphony, CBS Orchestra and Baltimore Symphony from 1943 to 1954. He died in February of 1989 of liver cancer. |

© 1989 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at Ilmers home in Evanston, Illinois, on April 4, 1989. Portions were broadcast on WNIB two weeks later, and again in September of that year, as well as 1994 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.