BD: When they offer you

one of those parts, are they aware that it might mean the end of your

career?

BD: When they offer you

one of those parts, are they aware that it might mean the end of your

career? WW: Yes and no. She

adores the children and feels they are an extension of her. She

takes great pride in the fact that she’s been the

mother-figure for them. She has a great love for them and takes

pride in their growth.

WW: Yes and no. She

adores the children and feels they are an extension of her. She

takes great pride in the fact that she’s been the

mother-figure for them. She has a great love for them and takes

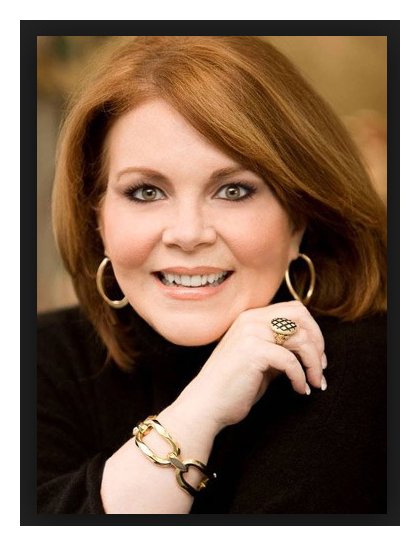

pride in their growth.| Born in Chicago in 1953, Wendy

White is a graduate of Wheaton College (1975, Bachelor of Music) and

the Jacobs School of Music of Indiana University (1978, Master of

Music). She won the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions in

1978. In 1979 she made her debut at the Lyric Opera of Chicago as

Smeraldina in Sergei Prokofiev's The

Love for Three Oranges. She appeared in two more roles with the

company that year: the Countess di Coigny in Umberto Giordano's Andrea Chénier and Giovanna

in Giuseppe Verdi's Rigoletto.

She later returned to the Lyric Opera as the 3rd Lady in Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart's The Magic Flute

(1986), Siébel in Charles Gounod's Faust (1987), Charmian in Samuel

Barber's Antony and Cleopatra

(1991), Susanna in John

Corigliano's The Ghosts of

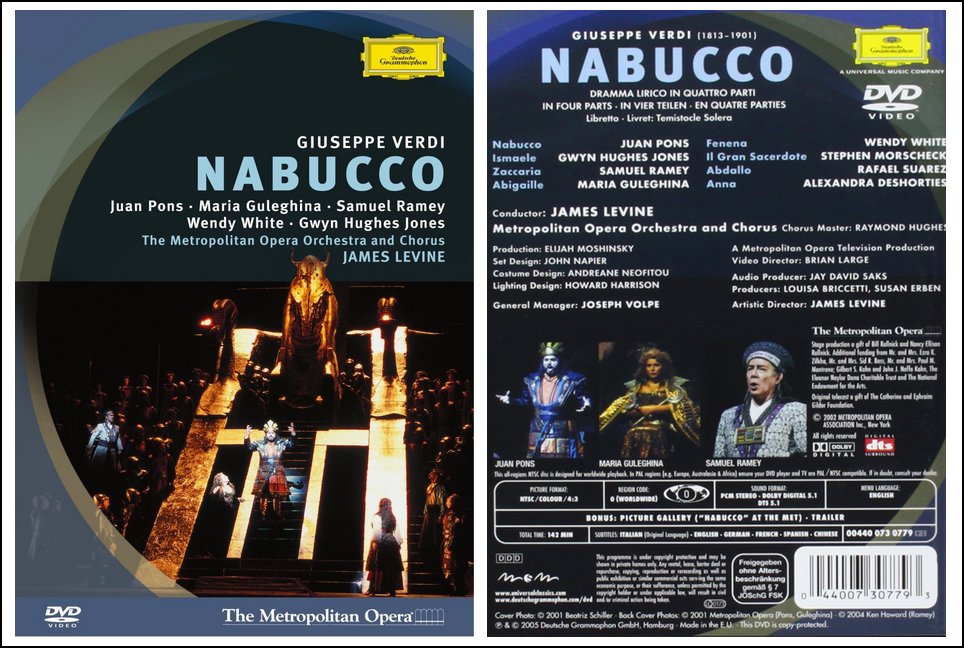

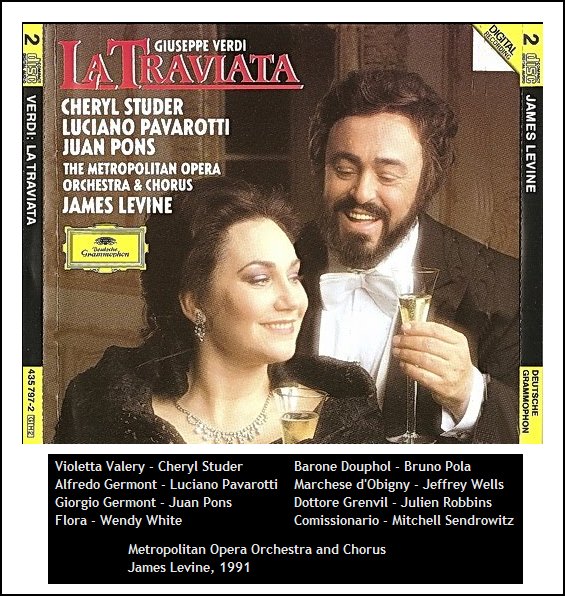

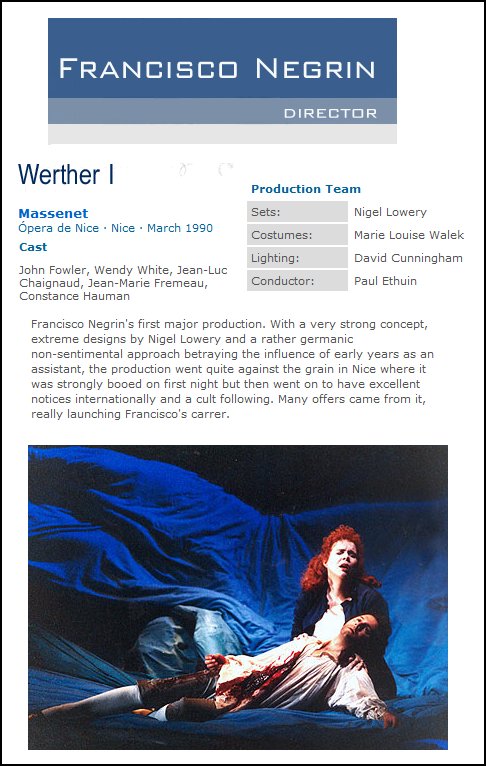

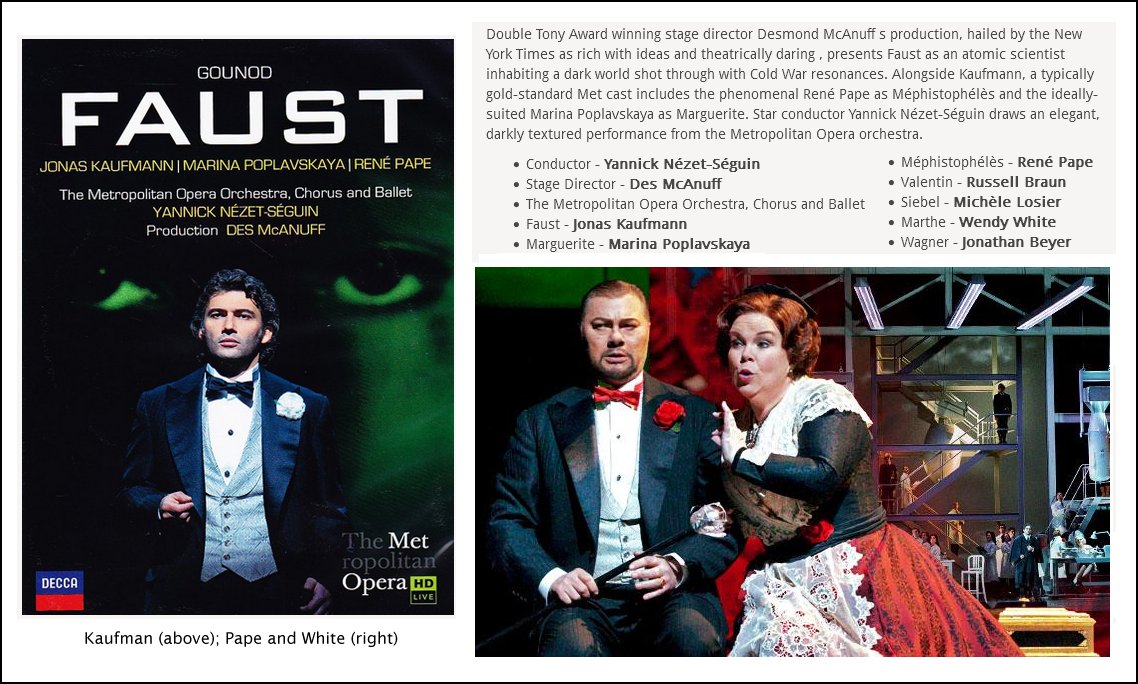

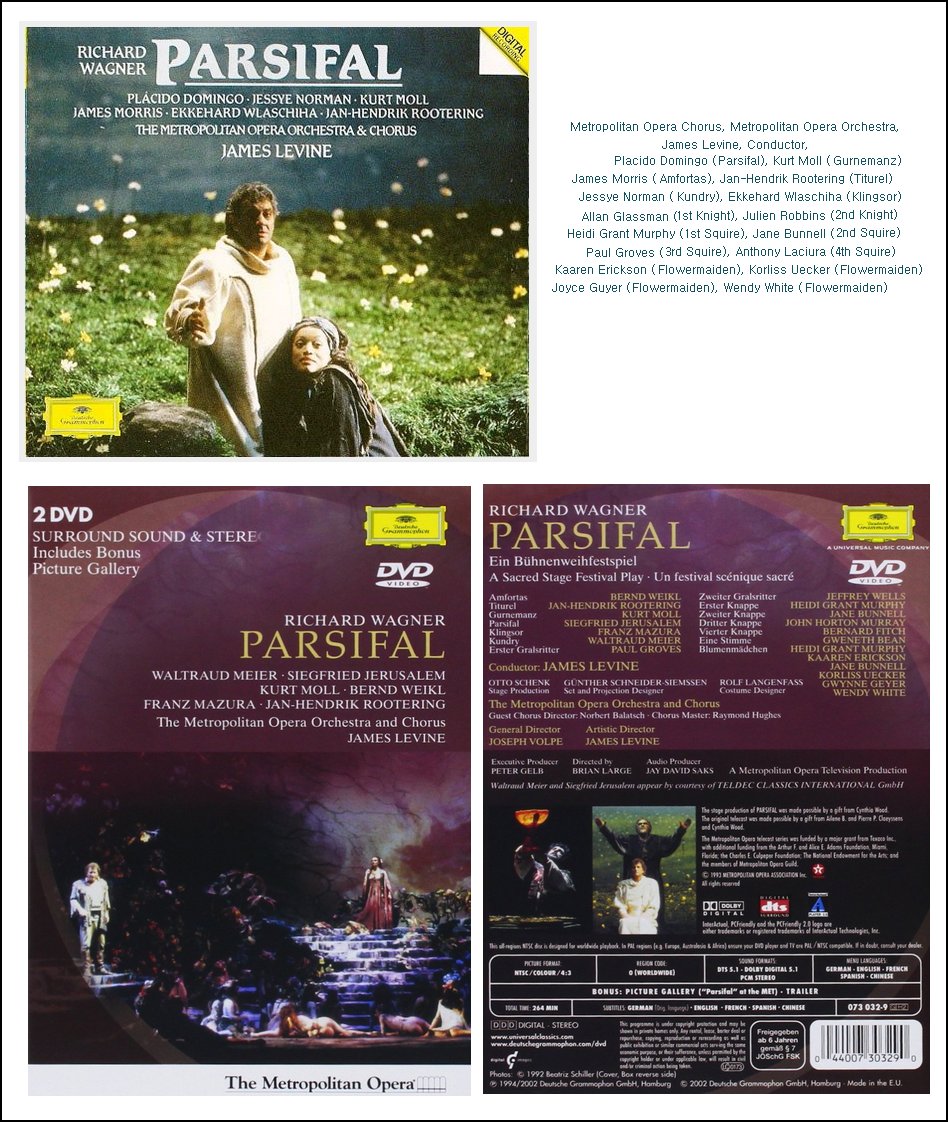

Versailles (1995), and Suzuki in Giacomo Puccini's Madama Butterfly (1997/1998). In 1982 White portrayed the role of Colombina in Ferruccio Busoni's Harlequin at the Houston Grand Opera. In 1984 she performed the role of Valencienne in The Merry Widow with the Washington National Opera. In 1986 she made her debut at the New York City Opera as Charlotte in Jules Massenet's Werther with Jerry Hadley in the title role. That same year she performed the role of Cherubino in Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro with the Fort Worth Opera. In 1987 she sang the title role in Georges Bizet's Carmen in Orange County, California under conductor Victor Borge. In 1990 she performed the role of Rosina in Gioachino Rossini's The Barber of Seville at the Cincinnati Opera. In 1999 she made her debut at the San Francisco Opera as Suzuki in Madama Butterfly. On October 16, 1989, White made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera as Flora in a new staging of Verdi's La traviata with Carlos Kleiber conducting. She has continued to perform annually with the company since, portraying more than 40 roles for the Met. She has appeared on numerous Live from the Metropolitan Opera broadcasts on PBS, including portraying the roles of Bersi in Andrea Chénier, Fenena in Nabucco, Marcellina in The Marriage of Figaro, Margret in Wozzeck, Suzuki in Madama Butterfly, and Tisbe in La Cenerentola. Some of her other roles at the Met include Anna in Les Troyens, Annina in Der Rosenkavalier, Baba the Turk in The Rake's Progress, Berta in The Barber of Seville, Brangäne in Tristan und Isolde, Carmen, Cherubino in The Ghosts of Versailles, Death in The Nightingale, Emilia in Otello, Erda and Flosshilde in The Ring Cycle, Federica in Luisa Miller, Giovanna in Ernani, Giulietta in The Tales of Hoffmann, the Innkeeper in Boris Godunov, Isabella in L'italiana in Algeri, the Kitchen Boy in Rusalka, La Cieca in La Gioconda, Larina in Eugene Onegin, Lola in Cavalleria rusticana, Maddalena in Rigoletto, Magdalene in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Mary in The Flying Dutchman, the Monitor in Suor Angelica, the Mother in L'enfant et les sortilèges, and Mistress Quickly in Falstaff among others. On the international stage, White has appeared with several major opera houses in Europe. In 1986 she sang the role of Dinah in Leonard Bernstein's A Quiet Place at the Vienna State Opera; a performance which was recorded for CD release by Deutsche Grammophon. She has also performed roles with the Hamburg State Opera, Opéra de Nice, and the Théâtre du Capitole. White has also had an active career within the concert repertoire. In August 1987 she was the soloist in Bernstein's Jeremiah Symphony with the Boston Symphony Orchestra at the Tanglewood Music Festival under the baton of the composer. In November 1990 she was the mezzo-soprano soloist in the world premiere of Ned Rorem's oratorio Goodbye, My Fancy with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and conductor Margaret Hillis. She has also sung in concerts with the Cleveland Orchestra, the Munich Symphony Orchestra, the National Symphony Orchestra, the Netherlands Radio Symphony, the New York Philharmonic, the St. Louis Symphony, and the San Francisco Symphony among others. On December 17, 2011, during a performance of Gounod's Faust at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, a stage platform collapsed as White was walking onto it. (This occurred a week after an HD broadcast with White, starring Jonas Kaufmann, that has since been released as a Decca DVD which is shown below.) She fell about eight feet and was injured. Ten months later the New York Times reported that she had not recovered from her injuries and felt abandoned by a company she considered family after the company canceled her contract. In August 2013 she sued the company for damages as a result of the accident. According to her lawyer, "She has capitulated to the reality that she's permanently injured and won't get better." |

See my Interviews with Kurt Moll, and Paul Groves.

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 29, 1987.

The transcription was made and much was published in The Massenet Newsletter in January

of 1989. Early in 2017, it was slightly re-edited, photos and

links were added and it was posted on this

website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award

- winning

broadcaster

Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975

until

its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His

interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since

1980,

and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well

as

on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.