Wagner in Chicago Before Lyric

The Resident Companies

at Home and on Tour

1910 - 1946

An Exploration and Compilation

by Bruce Duffie

Much of what is contained on this webpage appeared in Wagner News,

Volume XII, #2, March, 1985. I had been contributing interviews

to their magazine for five years, and also to a similar publication of

the Massenet Society. In 1984, I had written a long article, Massenet, Mary Garden,

and the Chicago Opera 1910-1932. By clicking the link,

you may see the updated version of that material. It also gives

the very solid reasons for restricting the dates of exploration.

The Wagner article followed a similar pattern, with text and charts.

There also was no need to stop at 1932, so I continued a few more

years, citing (as noted) an end point just before the formation of the

current company. The original has been slightly edited for this

webpage, and follows this brief introduction. I have also added

photos, and links which refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website.

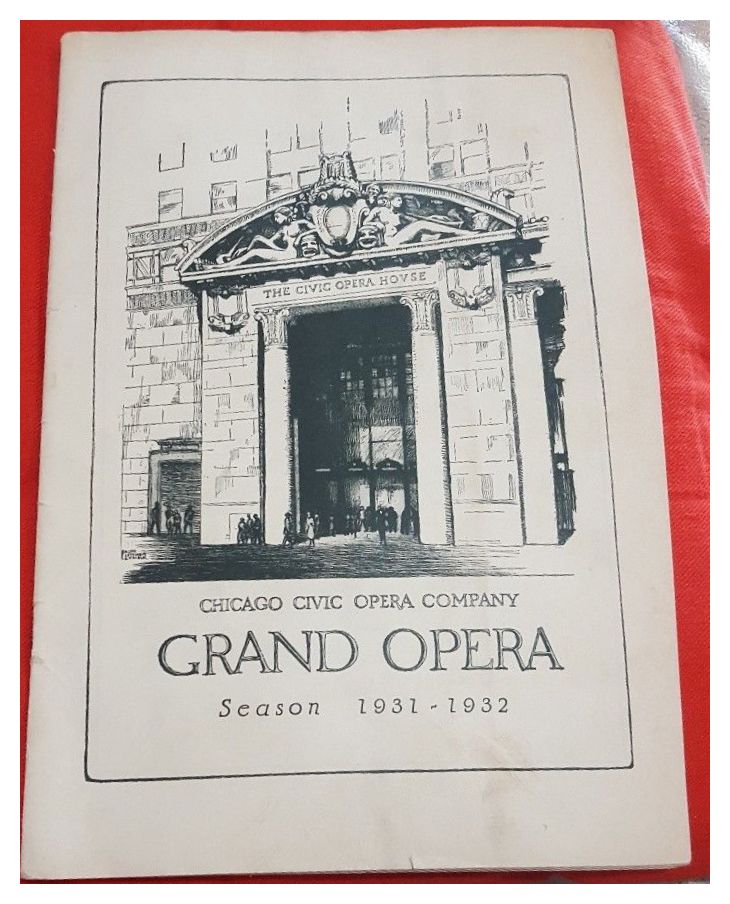

The title of this article indicates the history of ‘resident

companies’, and I have mostly limited myself to this area. However,

I have also included a few items where the Chicago Symphony provided accompaniment

for a visiting troupe (the Lohengrin of the Metroplitan Opera in

1891, which pre-dates the formation of a resident company), and the few

individual performances where singers were simply assembled in 1935 and

1946-53. There are also two news items from when the Chicago Opera

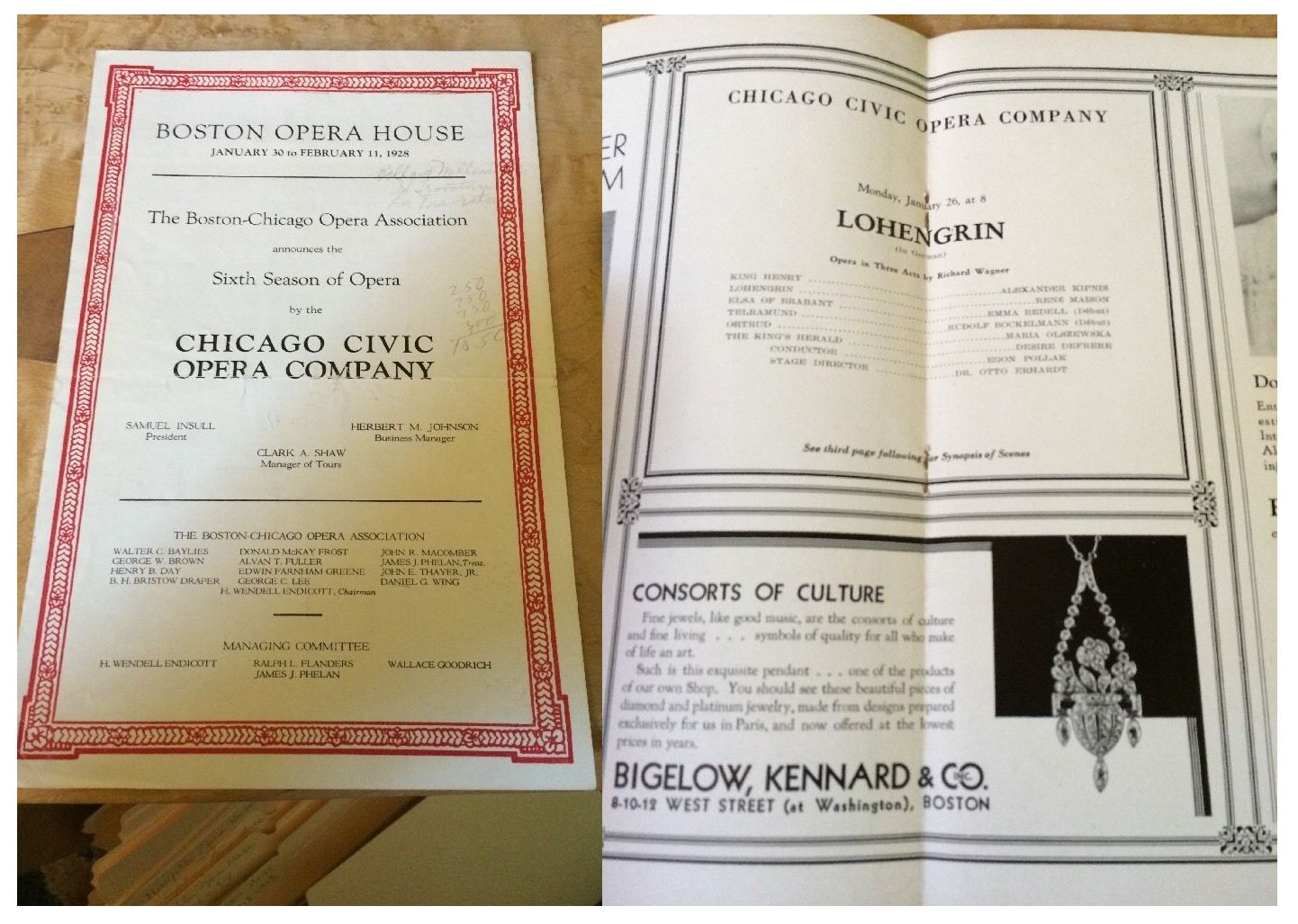

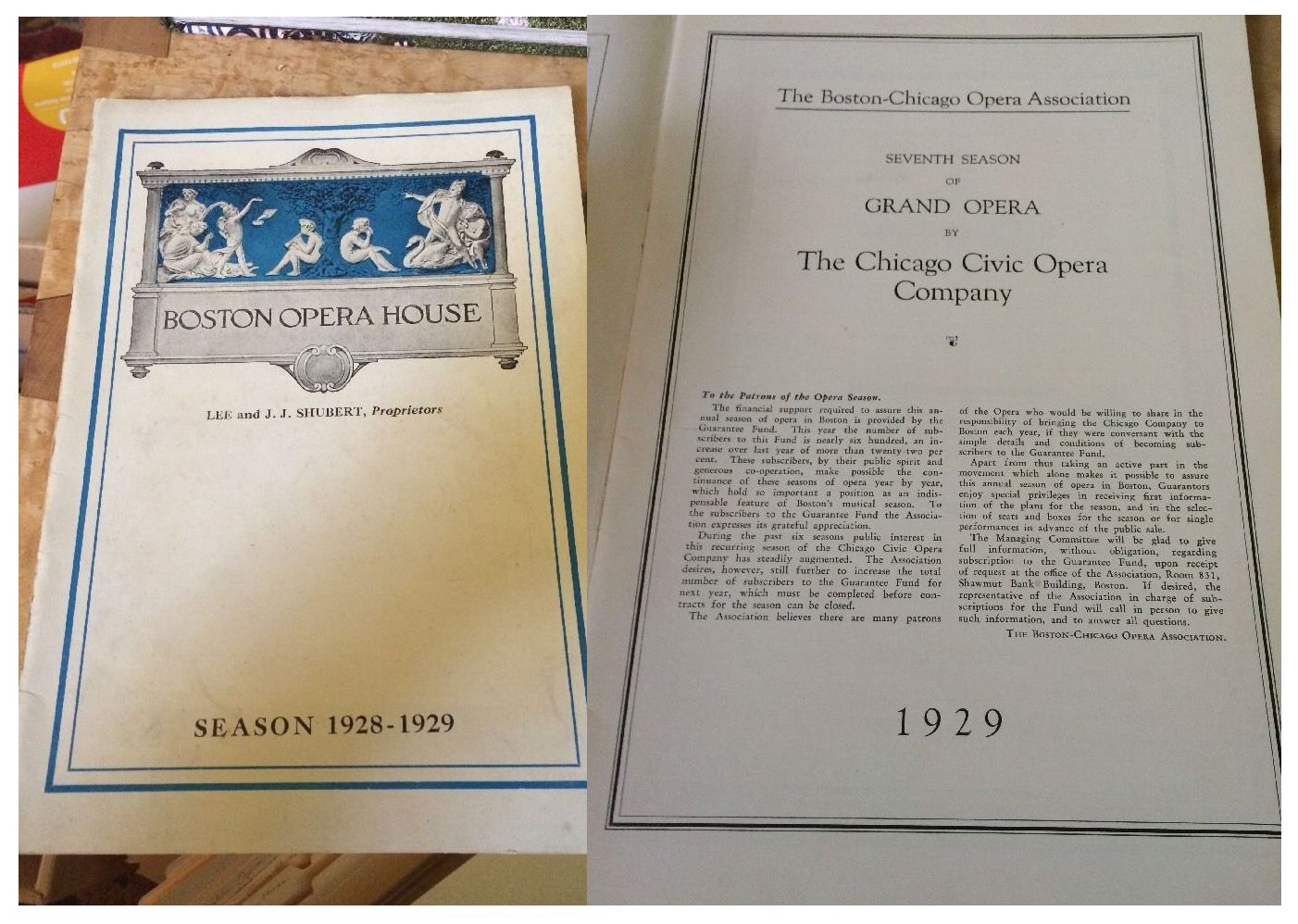

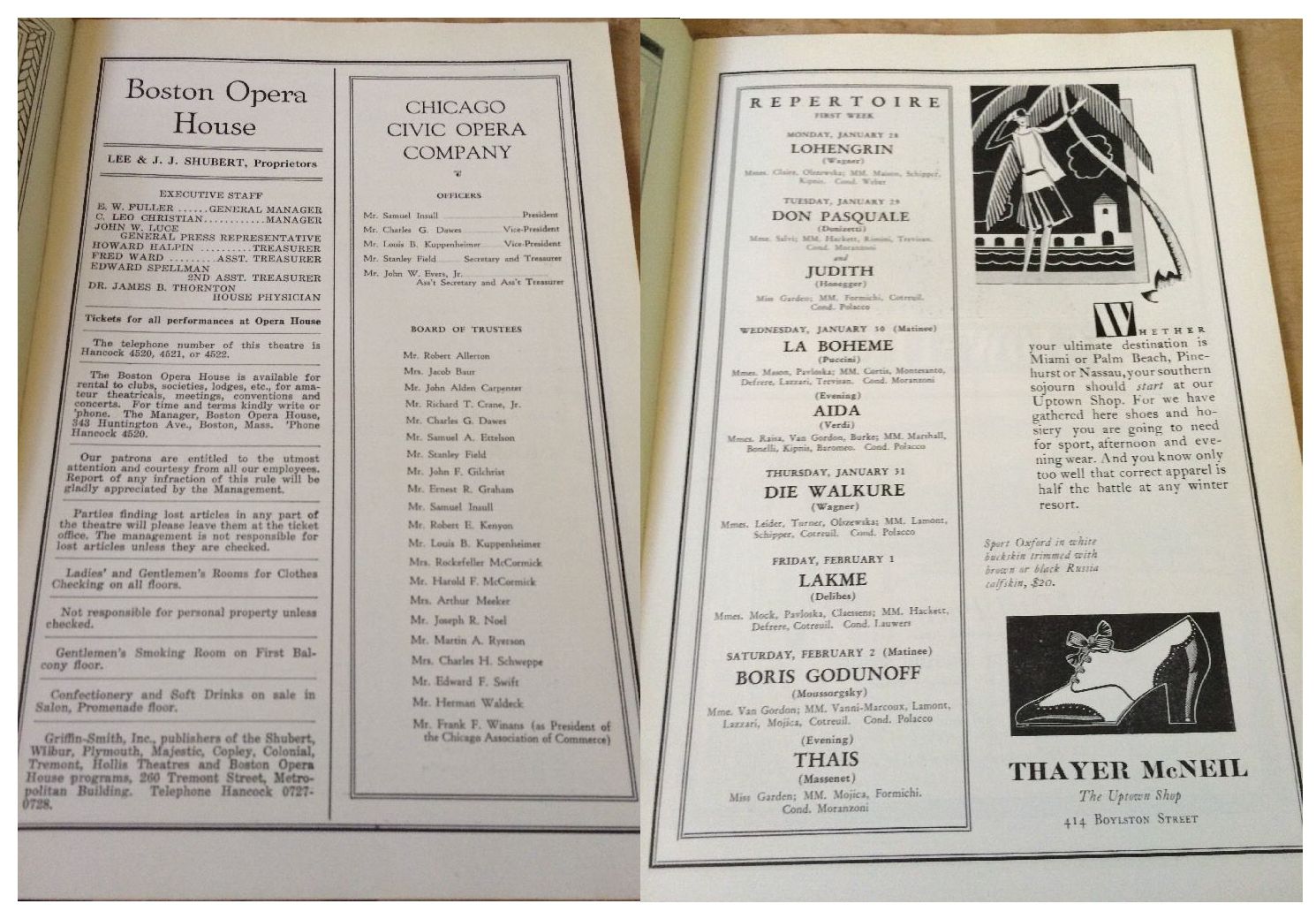

was on tour to Los Angeles, and three photos of programs from when they

were in Boston.

For the Massenet piece on this website, I added many brief biographies

and photos of the singers and conductors. Since a lot of the Wagner

performers also participated in other repertoire, quite a few of those

who are mentioned below can be found on the second and third pages of

the Massenet presentation. Those are indicated by an asterisk (*).

Other biographies and photos are included in the interview with Chicago

mezzo-soprano Sonia

Sharnova, and have a double asterisk (**). At some point I might

add the remaining ones, but for now, what is already posted will have

to suffice.

Now, to the Wagner . . . . . . . . .

===== =====

=====

--- --- --- ---

===== =====

=====

This survey of Wagner in Chicago before Lyric originally grew out of

a lecture which I gave dealing with Don Quichotte by Massenet.

Don’t worry, it all becomes clear, and even quite logical, very soon.

In the Fall of 1981, Lyric Opera of Chicago was presenting a revival

(!) of Massenet’s opera Don Quichotte as part of their season.

I had been asked to give a lecture about the opera before one of the

performances, and so some research was called for. I remembered

that the various resident Chicago opera companies before Lyric had done

quite a bit of Massenet, and had shown to great advantage their star,

Mary Garden*. So, I went through the annals for the resident companies

and found a great proliferation of both Massenet and Mary Garden in the

years 1910-1932. (There were various reasons for stopping in that

particular year which I need not go into in Wagner News, but they

are included in the introduction to that presentation, and can be read via

the link above.) Anyway, after gathering lots of wonderful information

about all of this, a lengthy article with a detailed chart was published

by The Massenet Society in January, 1984. But even before it was

finished, I began to wonder if the same kind of thing might be possible

for Wagner and his operas, and it is the result of that research which

are now reading.

* * *

* *

Lyric Opera of Chicago gave its first performances in February of

1954, so all anniversaries and notices of the company premieres date

from that time. Chicago, however, has enjoyed opera by resident

companies since 1910, and before that there were many visits by touring

companies both big and small. Opera was first heard in Chicago in

July 1850. A group of singers came by boat from Milwaukee to perform

La Sonnambula. The theater burned down the next night

— with no loss of life — but opera had

been heard and seen, and was now demanded by the public. By the 1890s,

Chicago was the railway transfer point for just about everyone, and, as

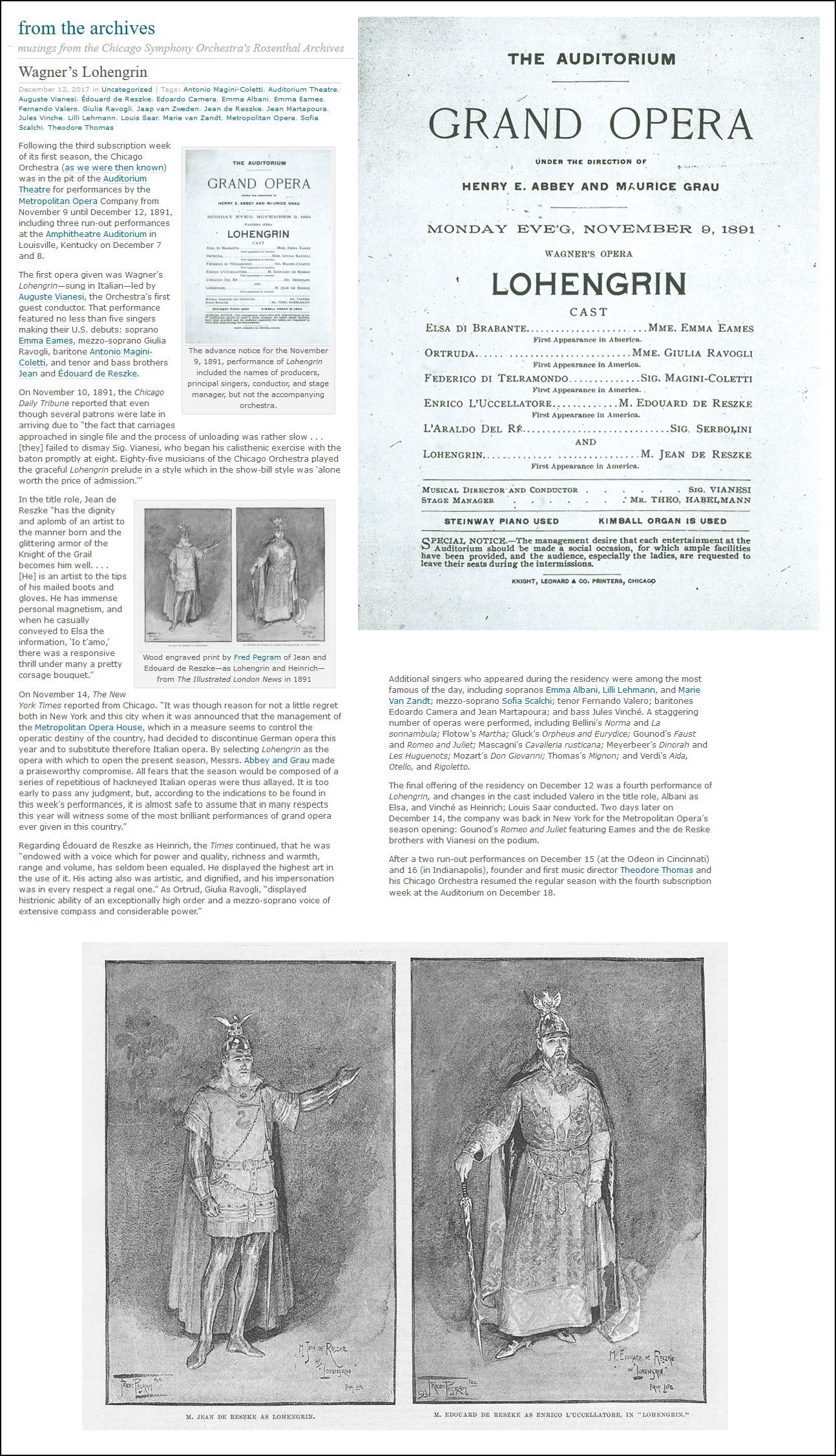

the hub of the nation, it heard opera in the newly-built Auditorium Theater

on Congress. This historic landmark was considered by Jean de Reszke**

to be the finest theater in the world for acoustics, and historians regard

the opening of the Auditorium as the real beginning of opera in Chicago.

[There are several color photos of both the exterior and interior

of the Auditorium Theater on the webpage of the Massenet Article which is

linked above.]

Until 1910, opera in Chicago was given by touring companies.

Several companies came with varied repertoire, and the Metropolitan showed

up from their first season, (1883-1884), until Chicago had its own company,

and soon they dropped the ‘Windy City’ from their tour list. Since

the Met did so much Wagner in their early days, a lot of it was taken

on their tours. A few highlights include a complete Ring

in 1888-89, as well as appearances by Lili Lehmann, Jean and Eduard de

Reszke, David Bispham and Walter Damrosch. All ten of the standard

Wagner operas were given, and there was even a performance of Rienzi.

Damrosch bought his own company to Chicago in April of 1895, and among

the cast was Johanna Gadski** who performed a real marathon

— Sieglinde on Monday, Elsa on Tuesday, Elisabeth on Friday,

and Eva on Saturday! Despite the absence of many well-known stars,

according to contemporary accounts, the company, under the leadership of

Damrosch, caught the spirit of Wagner. There were no star excesses

or pandemonium. Audiences seemed interested in the music no matter

which of the operas was being given, or who was in the cast. But not

every visit was successful. Apparently the 1899 tour of the company

under Abbey and Grau was a disaster, both artistically and at the box office,

and ten years later the operas again were poorly attended. However,

in the first decade of the new century, something was happening in New

York that would change the course of opera in Chicago forever.

* * *

* *

The story of the Hammerstein Opera Company in New York is well known,

and its five seasons he presented productions which were so spectacular

that the Met finally paid him to cease competing with their company.

In the settlement, the Metropolitan Opera Company acquired the assets

of the Hammerstein company, which included scores, sets, and the costumes

for the predominantly French repertoire. At this time, the financiers

and backers thought that an opera company in Chicago would not be directly

competing with the Met, so the newly acquired assets were sent west to

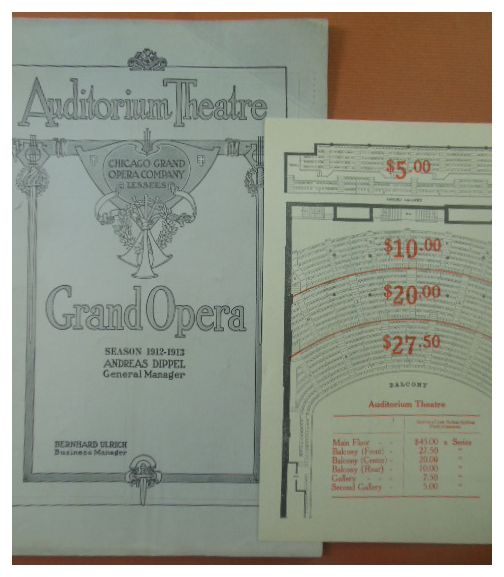

help start the Chicago Grand Opera Company. Harold McCormick* was

the president of the company, Charles Dawes* (later vice-president under

Coolidge) was the First Vice-President, Otto Kahn (then president of the

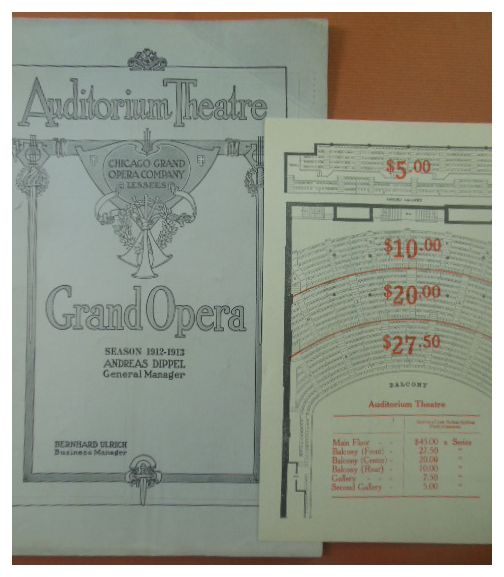

Met) was Second Vice-President. Tenor Andreas Dippel*, who by that

time was assistant to Giulio Gatti-Casazza at the Met, was named General

Manager, and the leading star of the company was Mary Garden. The

principal conductor was Cleofonte Campanini*, and in 1913 he became General

Director — a post he held until his death in December

of 1919. Aside from being a first-rate musician, he sought better

and more colorful stage pictures.

In a statement reminiscent of Wieland Wagner, Campanini said, “We

have the greatest singers, the greatest dancers, drama, and literature,

but we have forgotten that the big gift of nature is color, and we have

either filled our stages with neutral tones, or we have left them bare.

We have either killed the imagination of our audience, or we have over-worked

it, and we have not realized that emotions can be stimulated almost as

powerfully through color as through music and drama.”

He was concerned with all the aspects of production, and become a kind

of father-figure to the company. When he passed away, his casket

was taken to the Auditorium and placed center-stage amidst flowers and

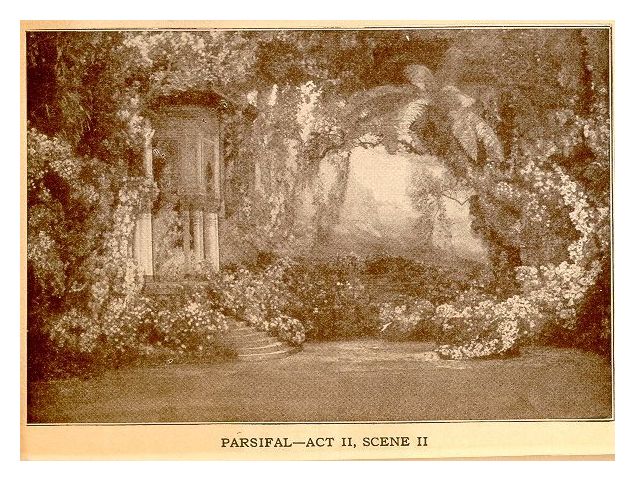

the sets of Parsifal.

The first season of resident opera in Chicago — 1910-1911

— heard no Wagner operas, but several of the Wagner singers

appeared in non-German roles. Charles Dalmorès*, was a French

tenor, but he sang several Wagner roles later in Chicago, including Lohengrin,

Siegmund, Tristan, and Parsifal. He also sang Lohengrin in 1908 at

Bayreuth. That first season in Chicago, he sang in Faust, The

Tales of Hoffman, Carmen and Louise. Johanna Gadski

appeared in Les Huguenots, and the season also had Caruso in Pagliacci

and La Fanciulla del West. [An extensive article about

Dalmorès can be found at the bottom of the first page of my Massenet

presentation.] Farrar and Scotti appeared in Tosca and

Madama Butterfly, John McCormack sang the Duke in Rigoletto,

as well as appearing in Cavalleria Rusticana and La Traviata.

To make things interesting, Dame Nellie Melba graced the stage in La

Bohème and La Traviata. The next season saw the

production of three of Wagner’s works — Lohengrin

and Die Walküre (each given four times), and Tristan und

Isolde twice. It should be remembered that in those days, operas

were not given many performances per season. That is to say, while

a great number of works were heard, each opera was only done a couple

of times, so the four performances of Lohengrin and Die Walküre

were a goodly representation. Today it is both a blessing and curse

that operas run six to nine times each season. It’s great that the

public has the opportunity to see them often and when it’s convenient,

but the management must be able to sell out those numerous performances.

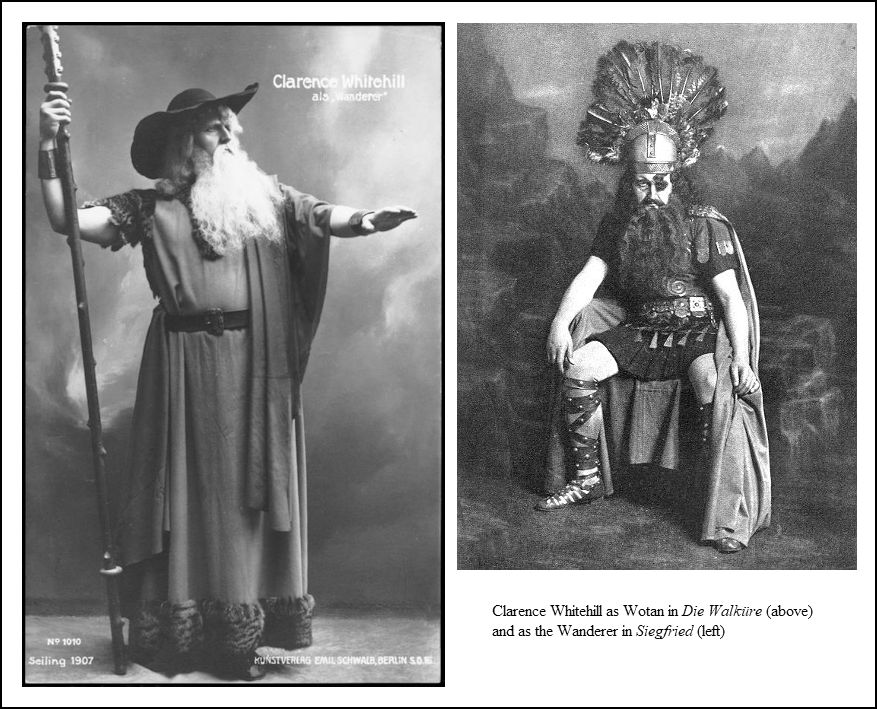

But to get back to that second season of 1911-1912, Dalmorès

and Clarence Whitehill were in all three Wagner operas, Ernestine Schumann-Heink

was both Ortrud and Fricka, Jeanne Gerville-Réache* was both Fricka

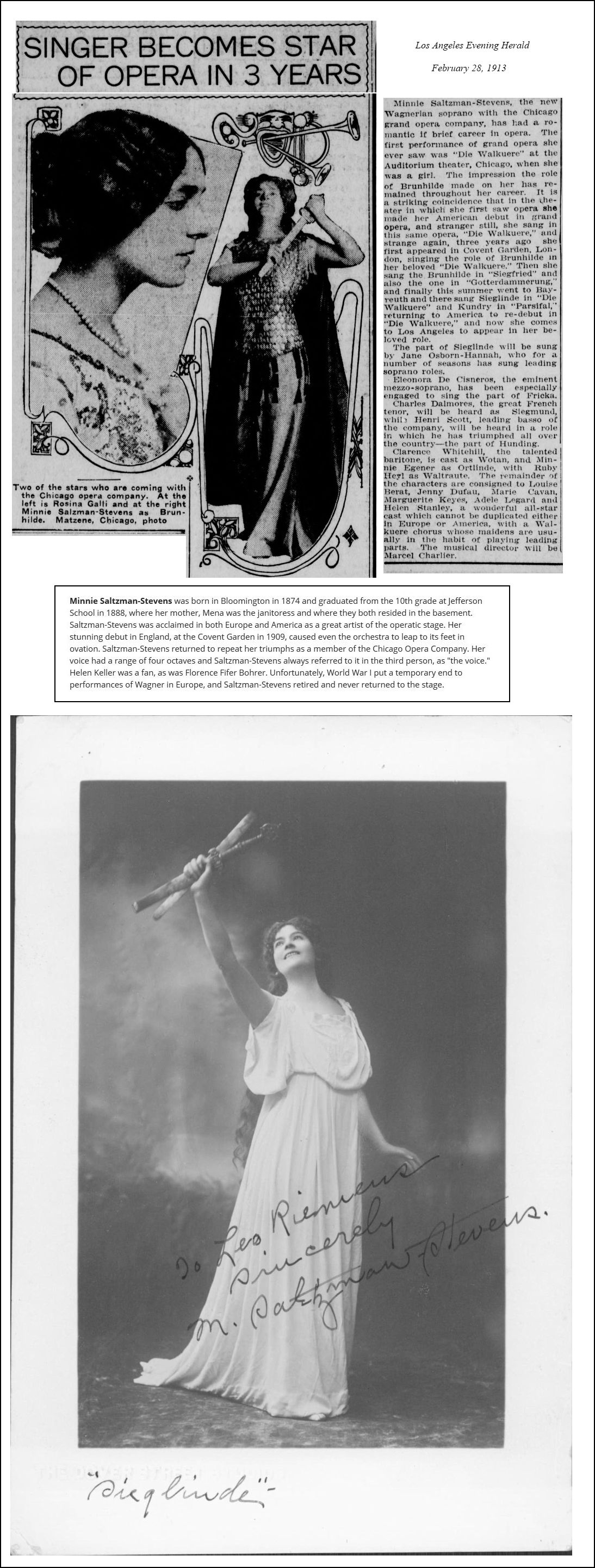

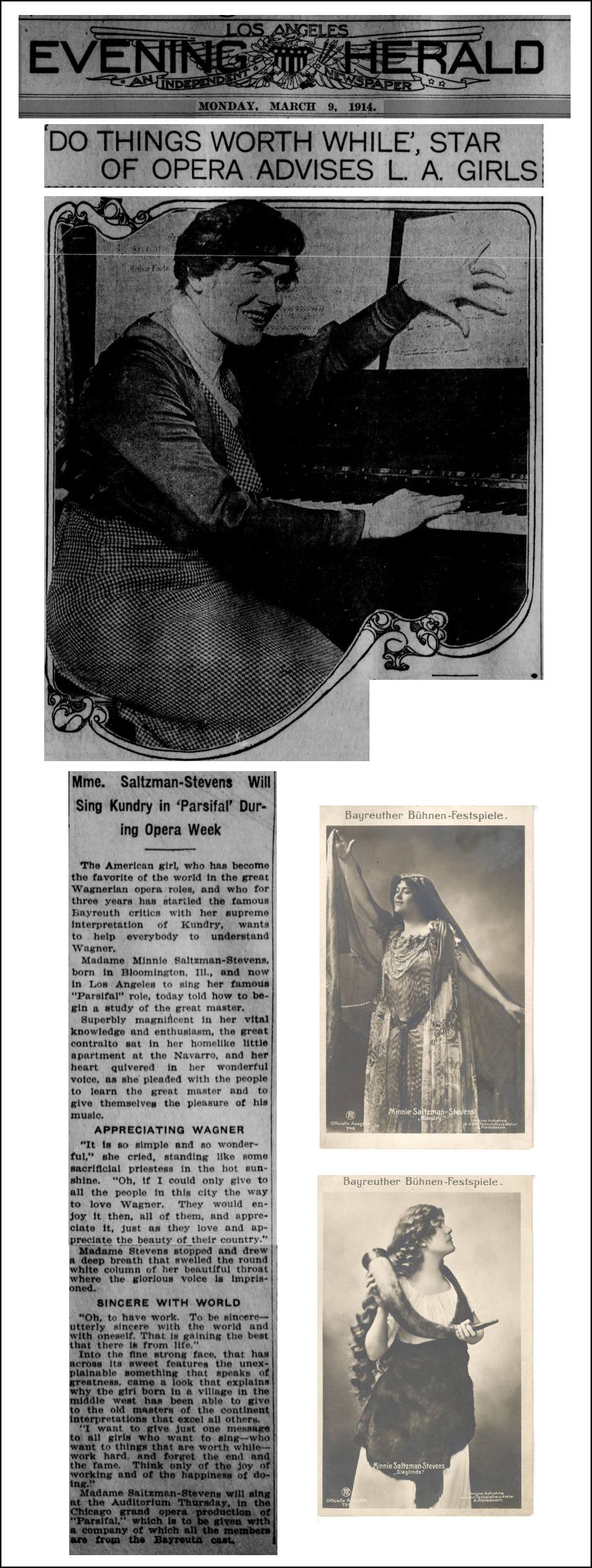

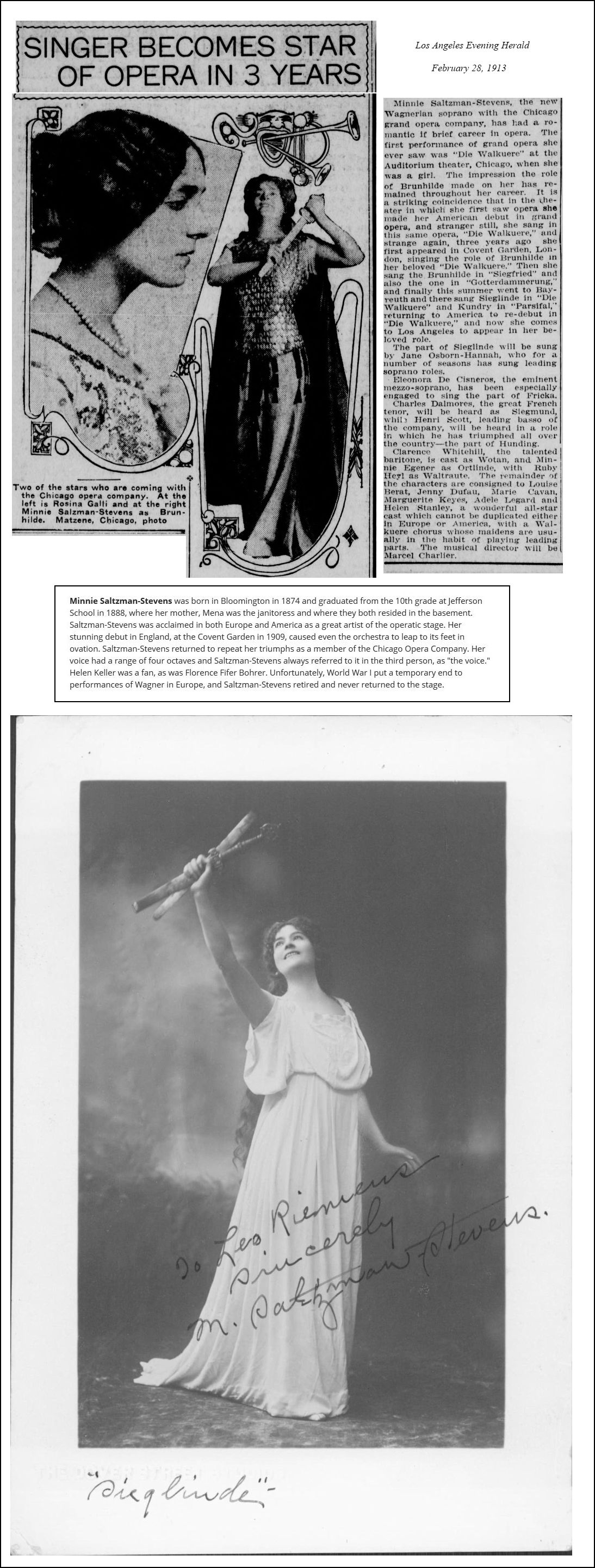

and Brangäne, and both Olive Fremstad and Minnie Saltzman-Stevens

were both Brünnhilde and Isolde. [Minnie Saltzman-Stevens

is shown above, and also at the bottom of this webpage, in articles from

Los Angeles when the opera company was on tour.] Aladar Szendrei

conducted Lohengrin and Die Walküre, and Campanini was

in the pit for Tristan. The next year these same three operas

were heard again with similar casts, and right up until 1917 the Wagner

wing of the opera companies in Chicago expanded, and even included a complete

Ring in two consecutive seasons. Lest one think that Wagner

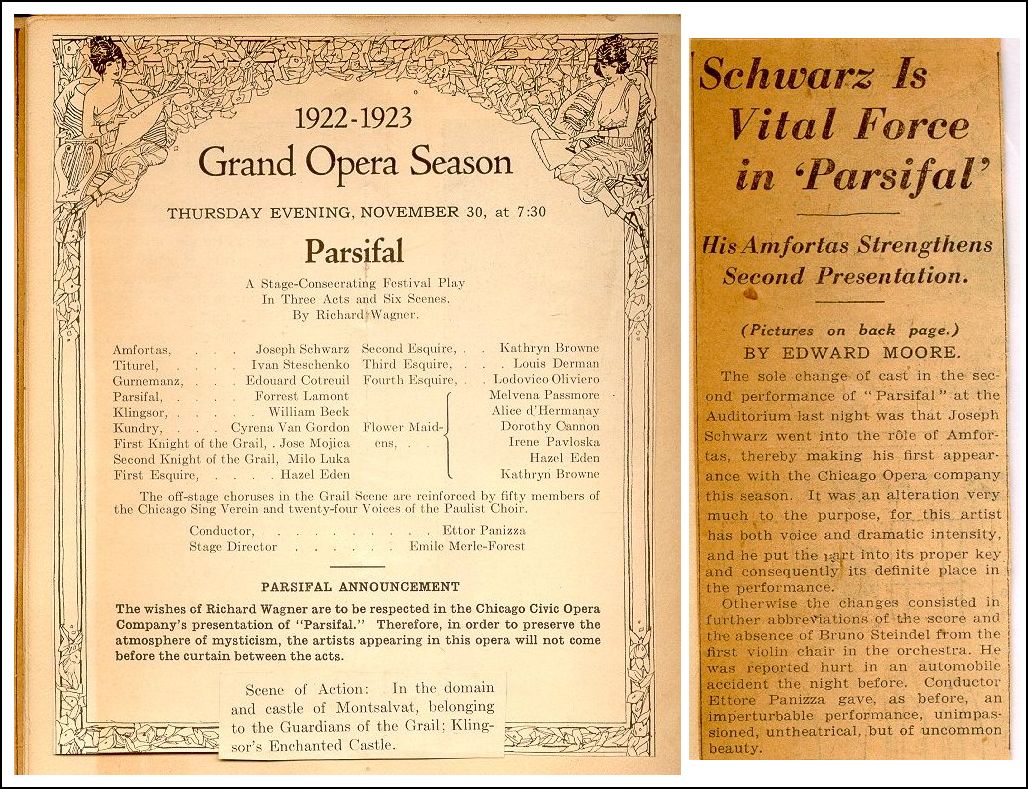

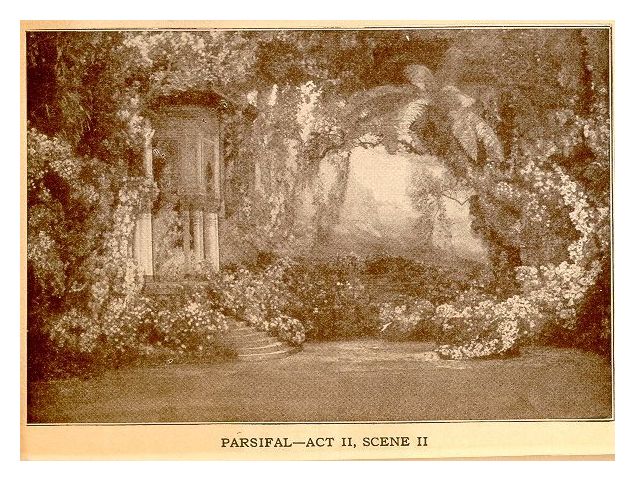

was simply tossed up on the stage to fend for itself, the company’s first

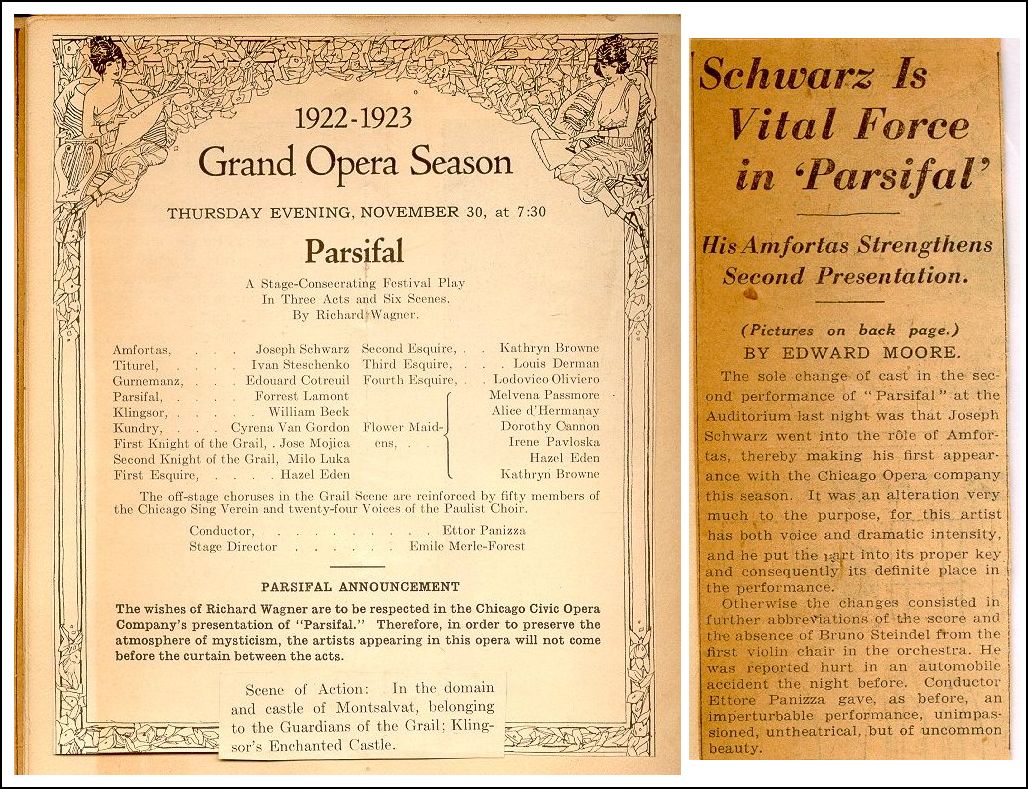

Parsifal in 1913 received fifteen full orchestral rehearsals

— an amount unheard of in that era, or even this one!

Not only did Campanini prepare the work carefully, but curtain calls were

forbidden between the acts, so the audience was given the best possible

presentation outside of Bayreuth. The two performances that season

were on Sundays, and the next year there was no season. When the

company was reformed in 1915, and renamed the Chicago Opera Association,

Tristan was given on the third evening. Then there were three

scattered performances of Tannhäuser in which the program

proclaimed that Act One took place in the Interior of Venus! The

four Ring operas were done on consecutive Sundays, and the following

week was Parsifal. The next Sunday was Aïda, then the

second Parsifal, and finally an extra Die Walküre

with the same cast to complete the Sundays in that season. Quite

a busy time for Whitehill, Francis Maclennan and Egon Pollak, but it must

have been a good idea because the following year, the Sundays were the domain

of Wagner once again, with the Ring, then Parsifal, Tannhäuser,

a New Year’s Eve matinee of Tristan, and finally a matinee of Lohengrin.

Eight Sundays in a row for Wagner — and Whitehill,

Maclennan and Pollak. Those three, along with Geraldine Farrar and

Cyrena Van Gordon* were also giving five performances of Königskinder

by Humperdinck during the same period. Incidentally, the Austrian conductor,

Egon Pollak, who was born in Prague and also died there of a heart attack

during a performance, was associated with the Bremen, Leipzig and Frankfurt

operas, and was for a decade the General Music Director of the Hamburg Opera.

He was generally regarded as the foremost interpreter of the works of Richard

Strauss, so presumably all the Wagner was in capable hands during this

era in Chicago.

Something strange did happen in the Götterdämmerung

in December, 1916. The forty-three men of the chorus went on strike,

and the choral lines were sung by Octave Dua* (the resident Mime), Désiré

Defrère* (the versatile baritone and stage director/manager),

Constantin Nicolay* (who had been the Second Knight in the 1913 Parsifal),

and a stage manager named Sam Katzman. But good, bad, or indifferent,

according to various accounts, all these performances of Wagner’s operas

were given uncut. That fact prompted one regular critic to lobby

loud and often in his column for the judicious use of the blue pencil.

He also referred to Wotan’s daughters as ‘Valkyrettes’. On the

other hand, another regular columnist, when noting that a German company

offered its tour cities a choice of abridged or unabridged performances,

stated, “Those who have experienced this gargantuan

system of operatic pleasure will understand it is the preferable way, despite

the apparent inconveniences.” Wagner, however,

was to suffer the same fate in Chicago that he suffered elsewhere in America.

The First World War brought about a huge amount of anti-German sentiment

all across the country, and Wagner was simply not given in most places

for a while. Indeed, the first Ring in 1916 was well-received,

but the second year Campanini steadfastly brought it back, but it played

to slight houses. After that matinee of Lohengrin in January

of 1917, Wagner disappeared from the boards until Christmas Eve of 1920.

Five performances of Lohengrin and Die Walküre

— both in English — were heard in the last

few days of that season. But by the following fall, Tannhäuser,

Lohengrin, and Tristan all returned in the original German

language. Regarding the controversy of language, Frederick Donaghey

wrote in the Chicago Tribune in December of 1918, “The thing

to be done in Wagner’s operas when put back on the American stage is to

use English text, to cut them into humane lengths, and to prevent German

singers from messing them up. The Germans among us, of course, will

not go to hear the operas after such revisions, but the Germans among

us never went to hear the operas when they were given in German, uncut,

by German singers. Wagner, rightly edited, could easily be made as

popular as Puccini, and such editing would put away all the traditions and

practices when his operas are re-staged. Also, a fair one-third of

the music could profitably be cut out and placed in a museum for preservation.

As to the performers, most of the good Wagner singers have not been German.

The four parts of the Ring, and two or three of the other operas

are good, in the best conditions, for one performance a season in Chicago.”

* * *

* *

The season of 1921-22 was to be the final one under the auspices

of Harold McCormick. He wanted to go out in style, so he had his

board of directors name Mary Garden as General Director. She produced

a stunning season, and ran up a deficit of just over a million dollars!

In her autobiography she said simply, “It was worth it,” and McCormick

paid the tab. In the fall of 1922, the company was restructured

and called the Chicago Civic Opera, and the man who ran the show was Samuel

Insull, the utilities magnate. He tried for several years to run

the company like another of his businesses — as a

profit-making venture. During its decade, the company gave a few performances

of one or two Wagner operas each season, and gradually the German wing

was rebuilt with often successful presentations and generally distinguished

casts. Henry Weber* made his debut conducting Tannhäuser

at the age of just twenty-three. Over the years, he proved himself

a valuable and distinguished asset to the company. A review a

few years later called him, “One of the brilliant,

learned, and alert conductors of this generation.”

He also became music director at WGN, the clear-channel Chicago radio

station, and he married his Elsa, Marion Claire*.

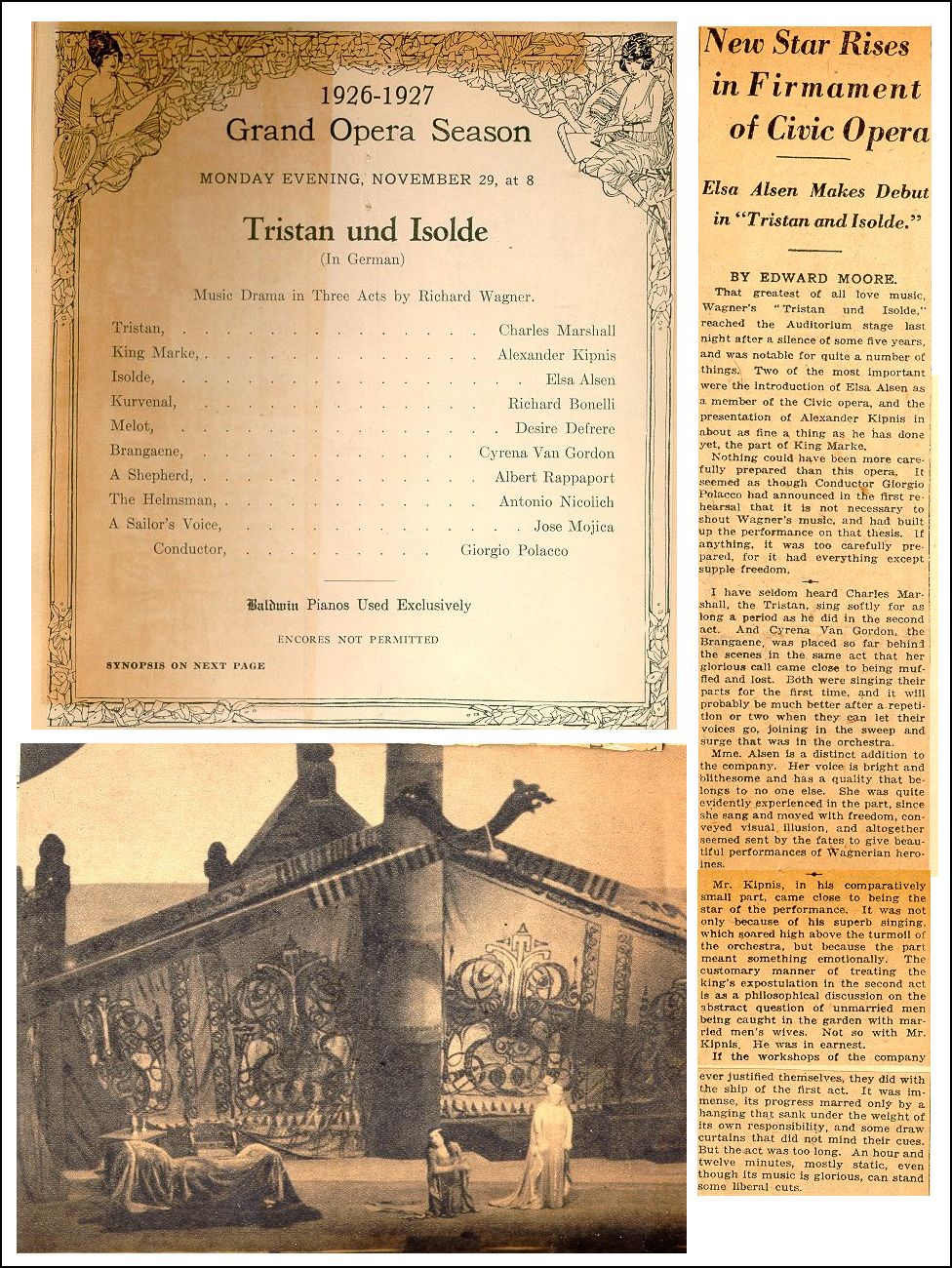

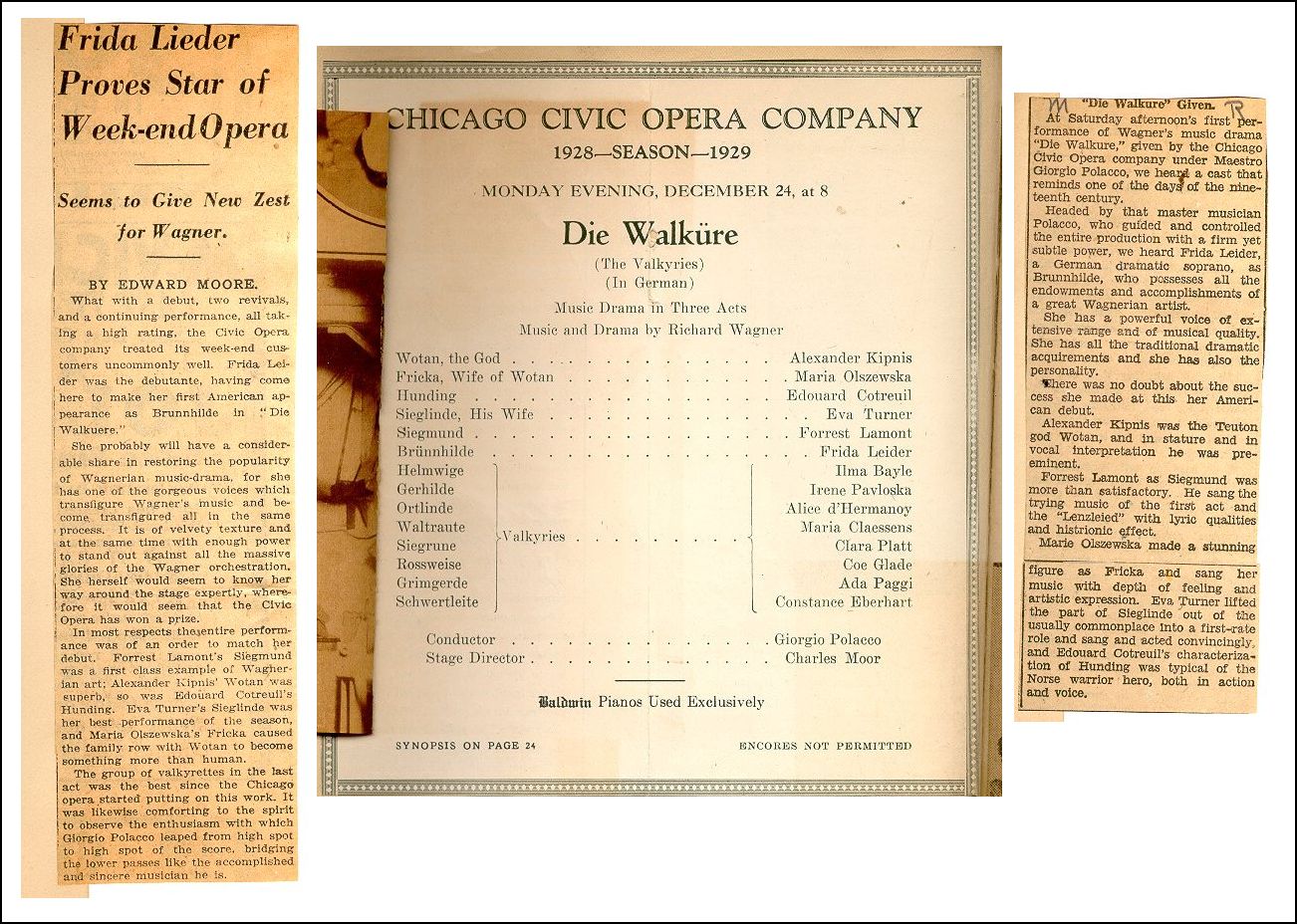

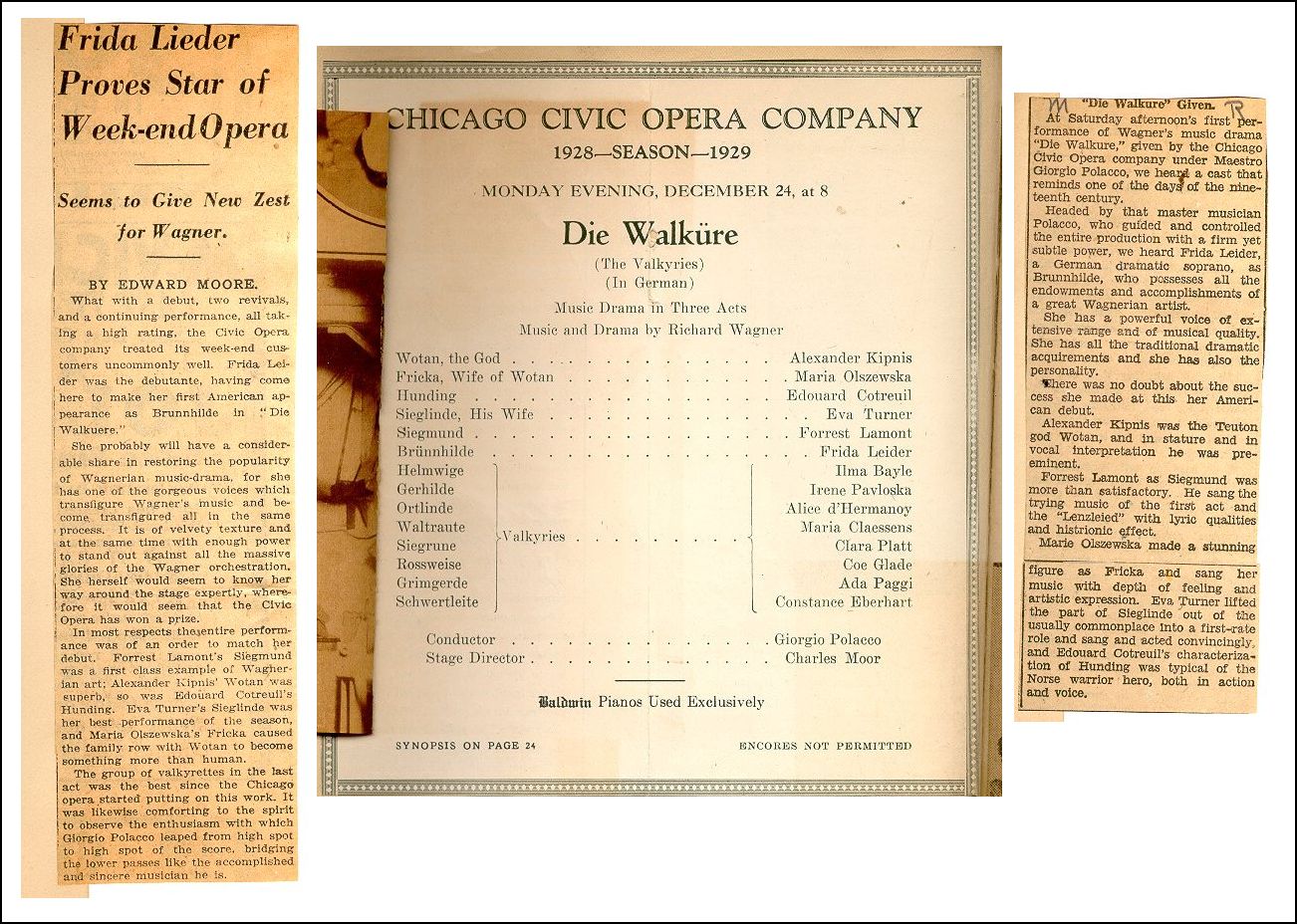

Giorgio Polacco* was responsible for most of the Italian operas done

during this period, but as you will see in the accompanying charts, he

led performances of Die Walküre and Tristan. One

patron remarked, “When Polacco conducted, it was

as if the music were coming out of the end of his baton.”

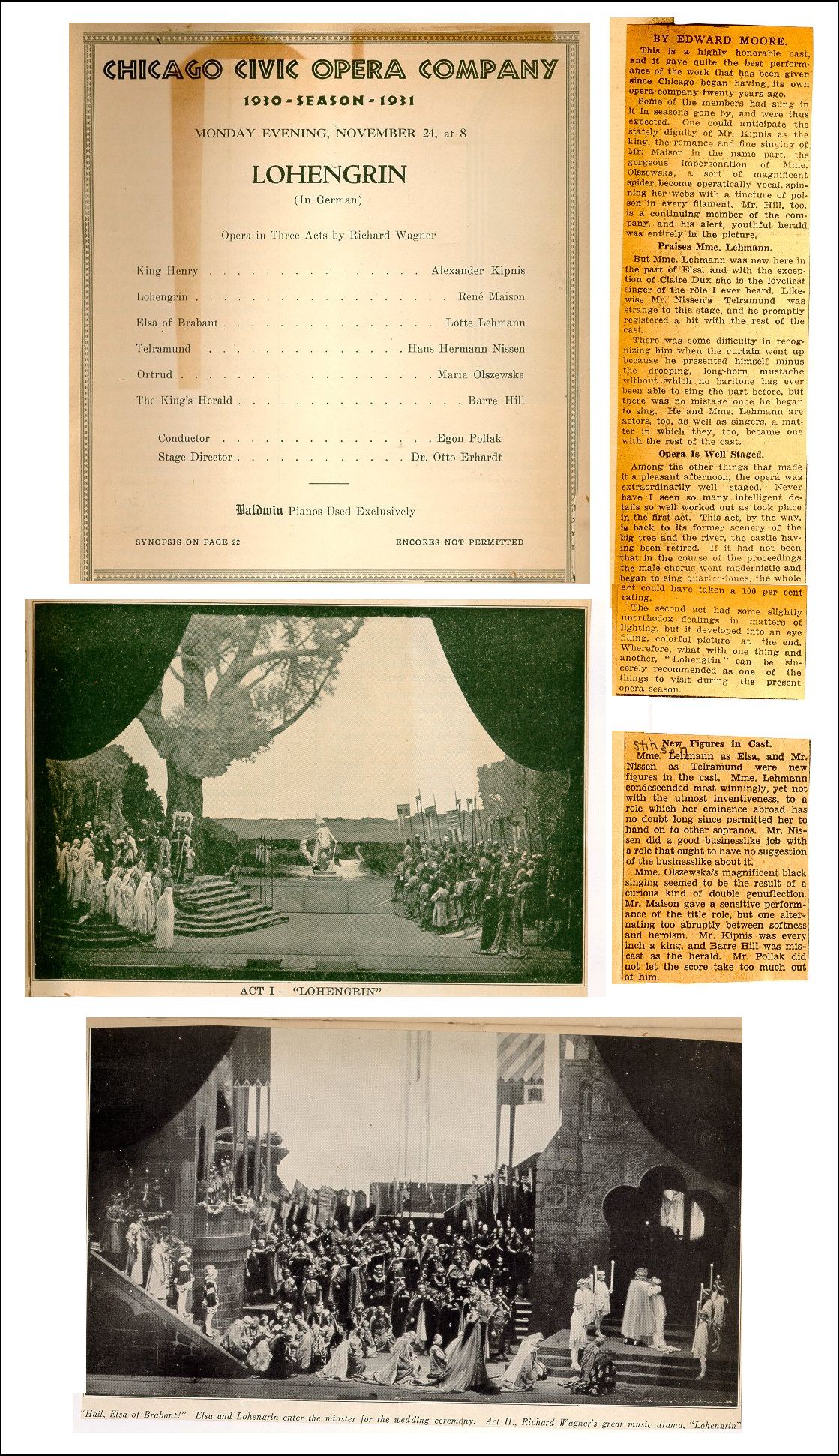

Perhaps the greatest individual portrayal was Maria Olczewska** as Ortrud.

A critic wrote, “Vocally, dramatically, temperamentally,

she would seem to have been sent upon the earth for the purpose of playing

the part.”

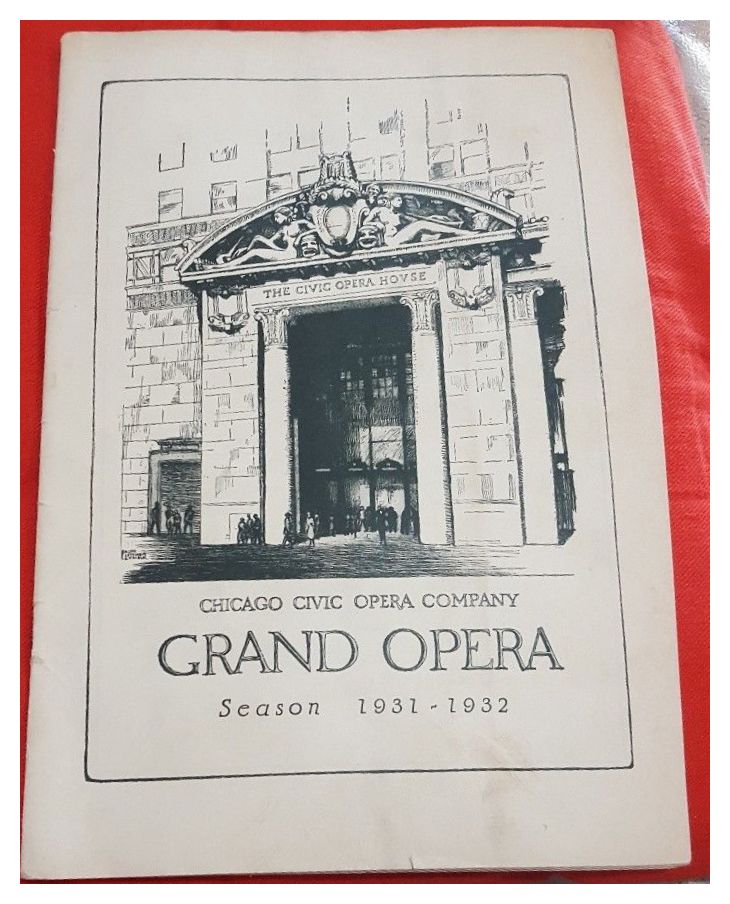

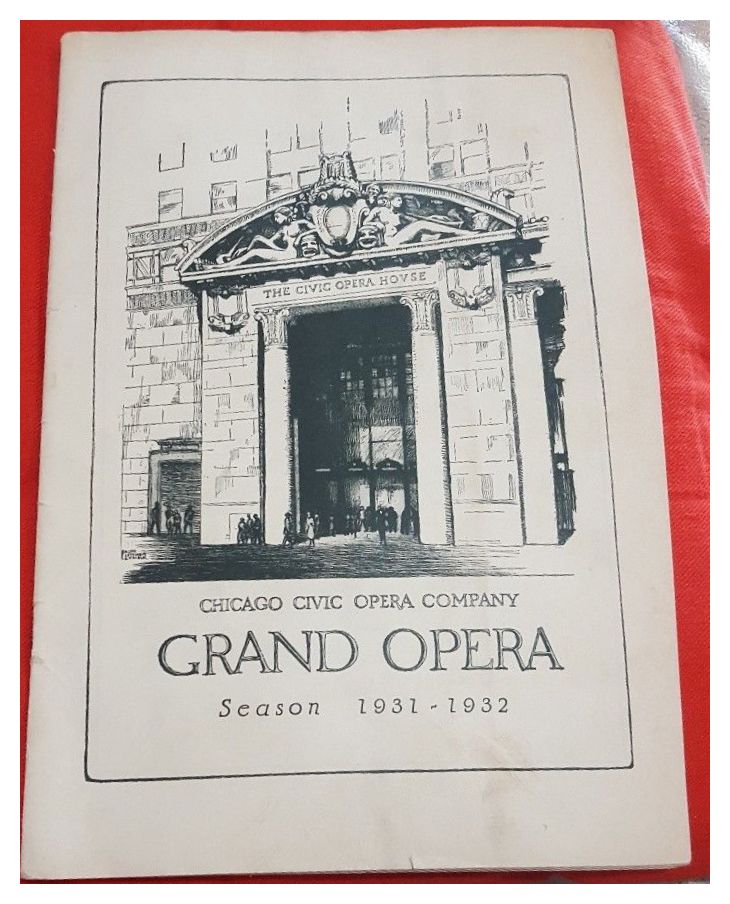

Along about this time, Insull announced his most ambitious plan

for the opera company. It was to be a building housing not only

the theater, but also offices. Eventually, the rent from the commercial

space would support the opera company, and in November of 1929, just six

days after that fateful stock market crash, the new Civic Opera House

on Wacker Drive was opened. It was a thrilling occasion, and even

though it didn’t quite work out the way Insull envisioned it, that is

where opera is given today by Lyric, and Chicago’s opera house is in the

Guinness Book of Records as being the tallest in the world. [As

with the Auditorium, there are several color photos of the Civic Opera House

on the Massenet webpages. Also, to see a painting which is a fantasy

on one of the architectural details of the building, click here. ] Despite

the collapse of Wall Street, the last three years of the Chicago Civic

Opera Company (1929-1932) saw more Wagner done than at any other time

in the city’s history — forty-four performances

of six operas. Although there were complaints about the length of

the performances, audiences attended dutifully, and remained until the

final curtain — often around 1 AM. Herbert

Witherspoon, a former bass who had come to Chicago in 1925 to head the

Chicago Musical College, and who would be named General Manager of the

Met just a few weeks before his death, became Artistic Director of the

company, replacing the ailing Polacco, and was dedicated to the idea that

opera should be first-class entertainment. He “paid particular attention

to the fact that, in times like these, people need the kind of entertainment

that will cheer them up.” In the middle of his brief but stunning

period, one critic wrote, “An opera house is not equipped which lacks an

adequate German department, and The Civic Opera Company has been building

one, which, until now is not merely adequate, it is distinguished.”

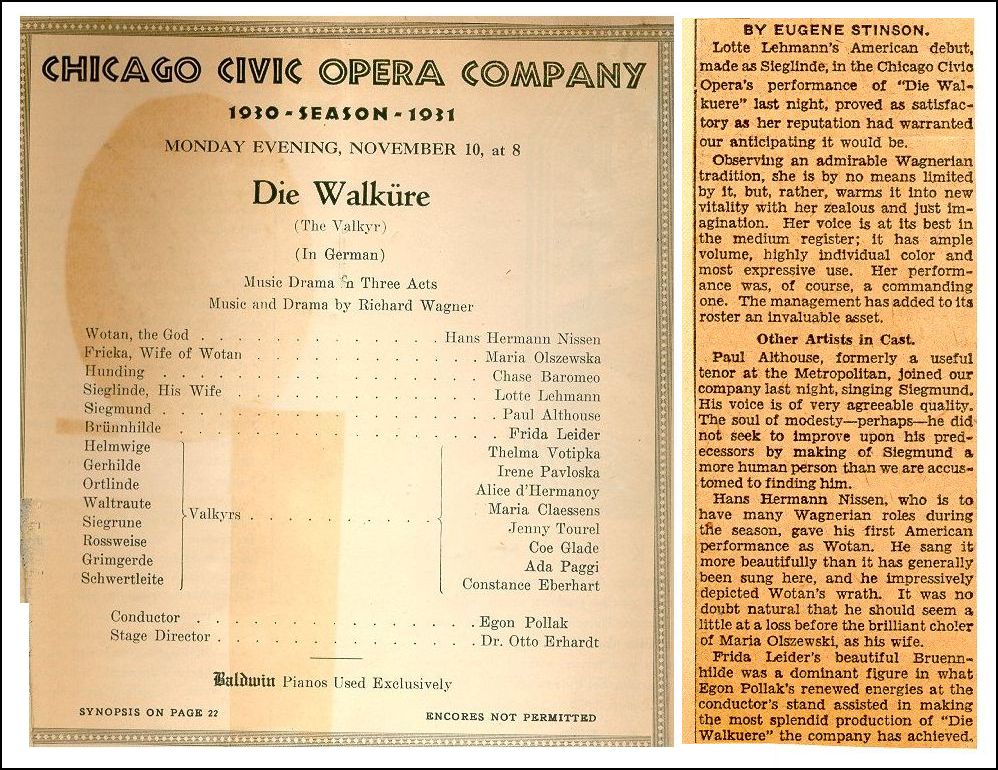

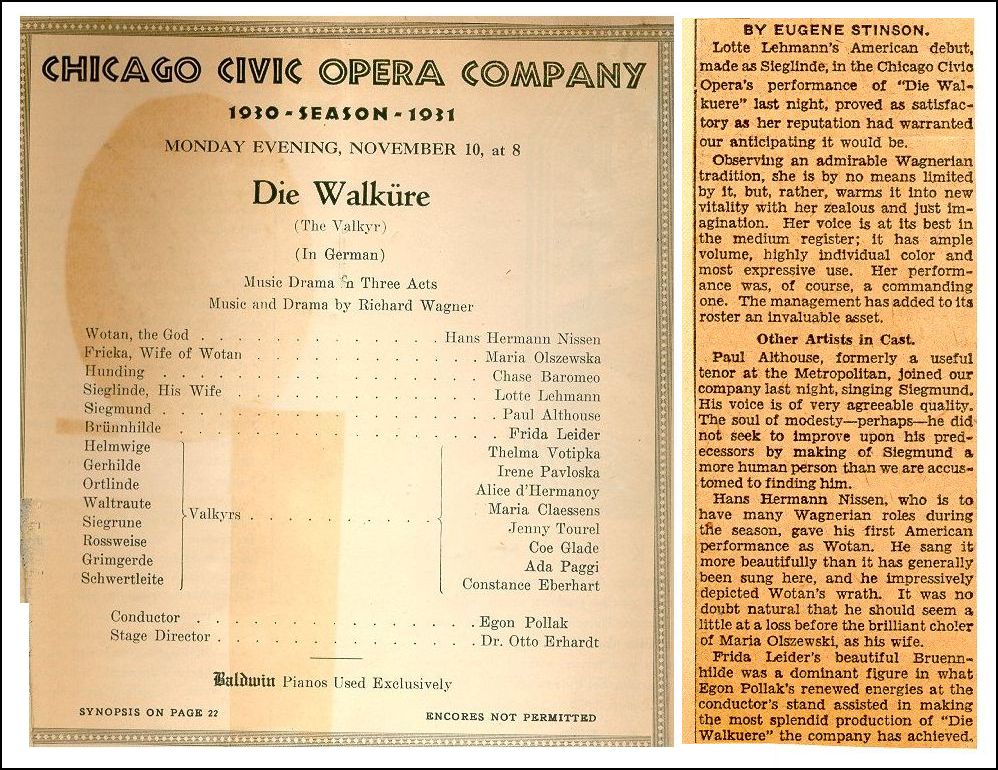

One of the most significant American debuts came on the second night of

the 1930-31 season. The Musical Courier called Lotte Lehmann’s**

Sieglinde “perfection of voice and of action.” Musical America

said her lovely voice had “a freedom and purity seldom discovered in German

singers. Her eloquence and artistry moved the audience to a great demonstration.”

Later performances that same season brought further accolades. “Her

Elisabeth was a spiritual figure, yet infused with reality and the charm

of life.”

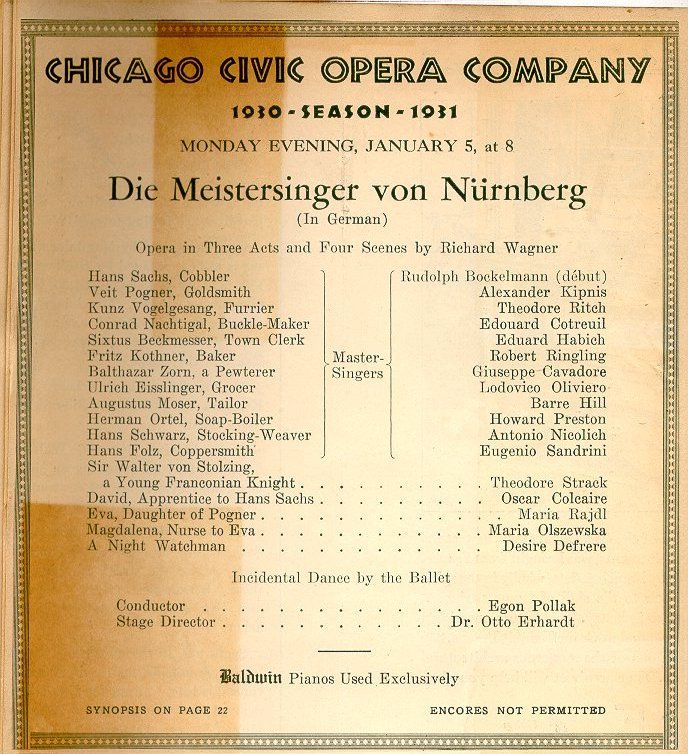

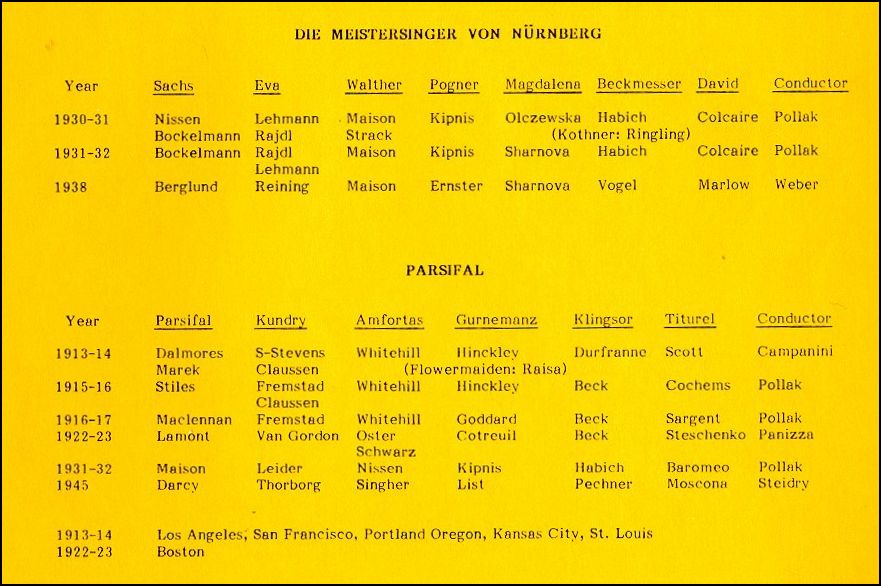

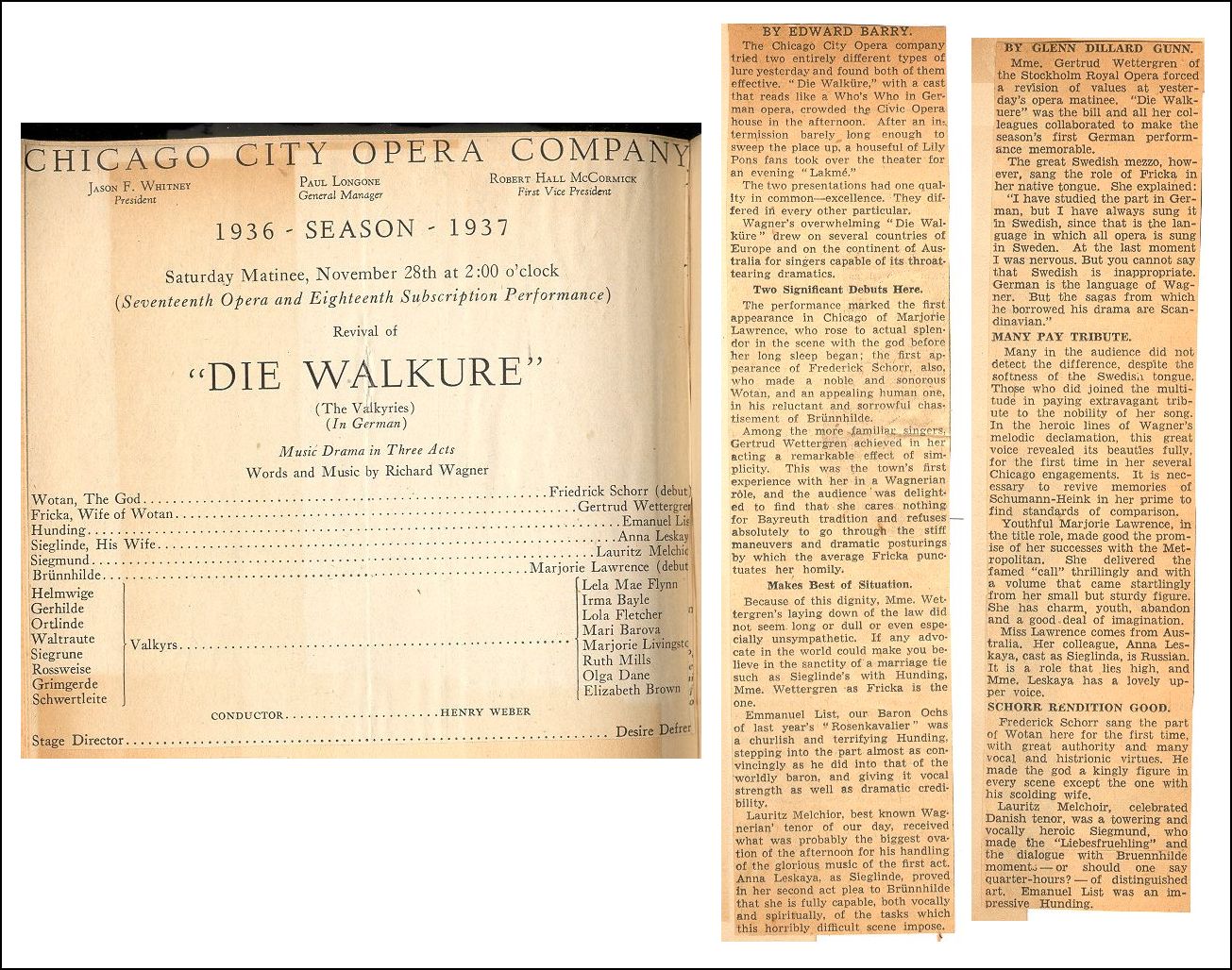

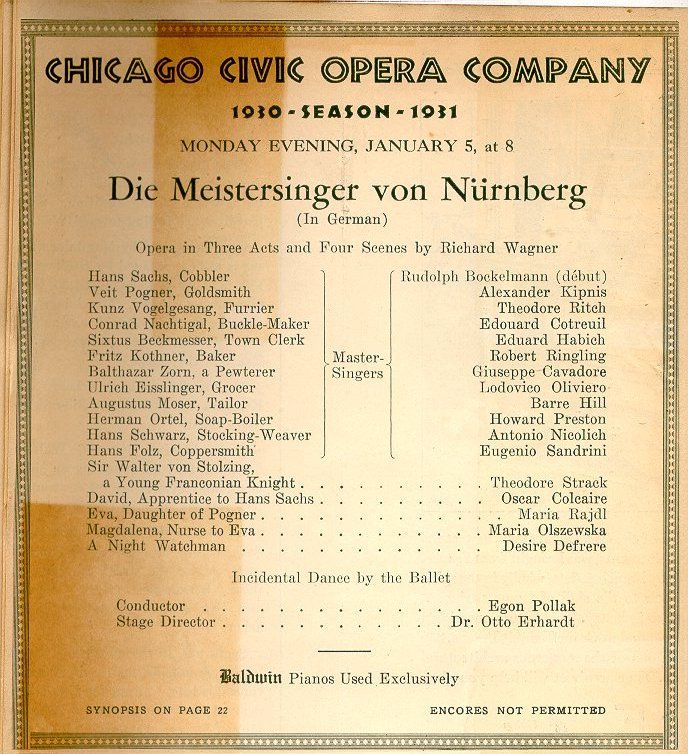

Finally, after having postponed it for nearly a decade, Die Meistersinger

was given (see program below-right), and Musical America

said that, “At the end, one’s thought was not of this or that individual,

or detail of the performance, but solely of the colossal genius of Richard

Wagner, which had been so lucidly and affectionately revealed.”

Besides the Wagner, there were productions of Der Rosenkavalier,

Fidelio, and Die Zauberflöte, as well as Mona Lisa

(by Max von Schillings) in the German wing, plus a whole host of Italian

and French operas done with very distinguished casts. Mary Garden

was still active as a singer, and the company managed to give several modern

works and world premieres. But even though this report notes many

stellar individual contributions, it is the sense of ‘company’ that made

the various Chicago troupes special. Baritone Joseph Schwarz* (who

sang Wolfram and Amfortas, as shown in program immediately below) said

it best when he commented, “Opera can be judged only by the success or failure

of its ensemble. To achieve success in opera individually, you must

be one of the ensemble. Together everything is possible; alone, nothing.”

But as we know, the financial world was collapsing, and so, too, was the

opera company. But what a blaze of glory brought this era to an end!

There was no resident company in 1932-33, and late that summer,

Paul Longone**, a one-time associate of Campanini, and later director

of a theater in Milan, was named Manager of the Chicago Grand Opera Company.

Even though sentiment was high to return to the Auditorium, financial considerations

made it mandatory to stay with the new opera house. There was just

one Wagner performance that season, and five the next, including the debut

of Lauritz Melchior**, called “the best Tristan who had ever appeared in

Chicago.” His debut, like his Met debut, was in an afternoon performance,

with another important artist being presented for the first time that evening.

In Chicago, the evening brought Ezio Pinza as Don Giovanni. After another

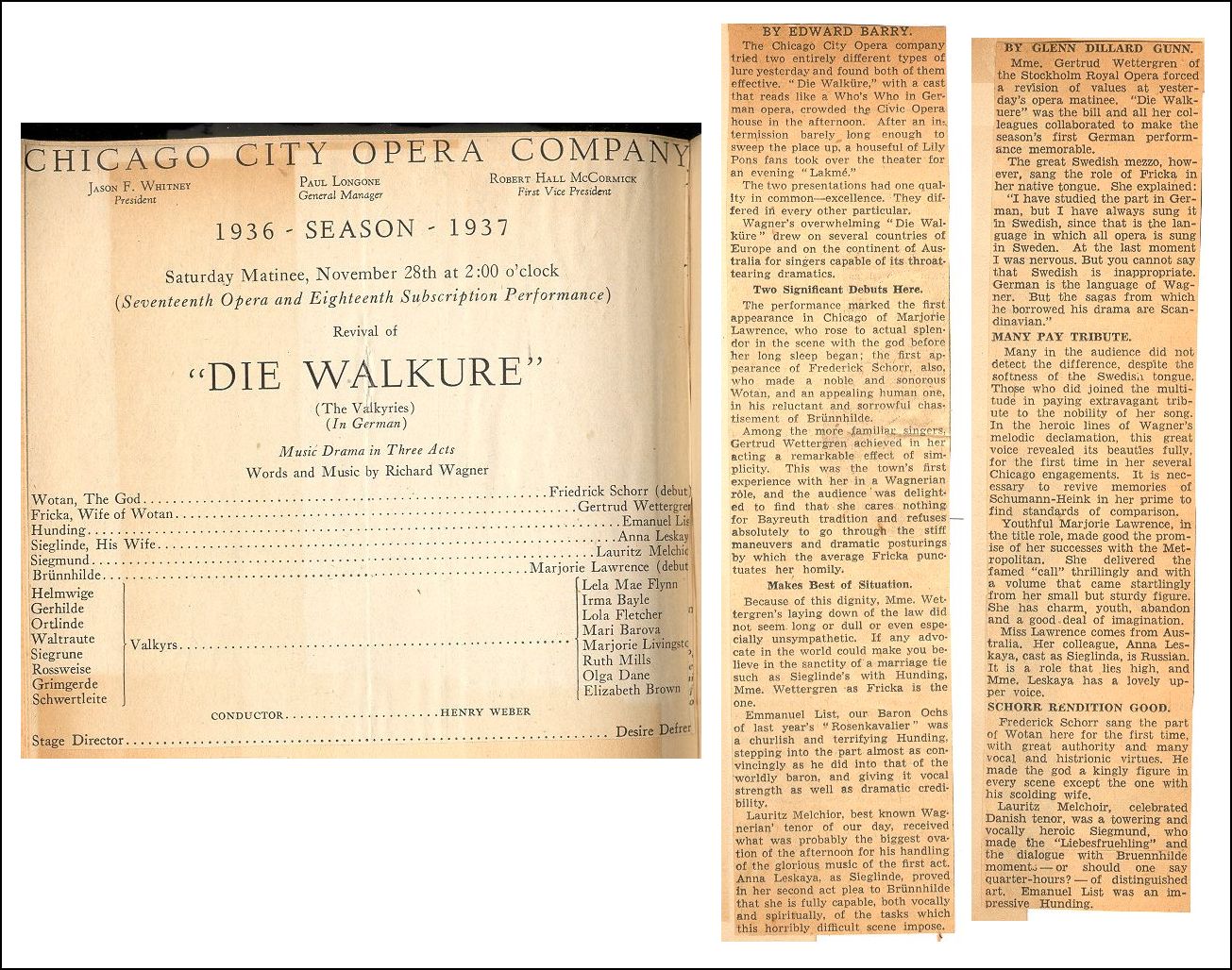

reorganization, the Chicago City Opera Company was in place by 1935, but

instead of being daring and adventurous, much of what was presented looked

and sounded the same as the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Kirsten

Flagstad’s** performances here aroused nearly the same amount of noisy clamor

that she engendered elsewhere. She “rose to heights of fury and splendor

which even she had ever exceeded.” The single performance she shared

with Giovanni Martinelli provoked a critic to call him “the most sensational

I have ever heard.” Musical America said, “Martinelli was a

Tristan worthy of Mme Flagstad’s Isolde. His youthful appearance in

the first act was captivating. Here was the young, daring knight of

legendary times.” It would be the only time in his life when he would

sing the role.

Interest in opera was keen, and guarantors somehow were found to

continue. The seasons that followed had their ups and downs, but

there were many sparkling evenings, and by 1940, Henry Weber, who by that

time was General Director, pushed the company to once again produce gala

opera. Critics heralded the “dawn of new opera in Chicago with everything

refurbished.” But, as always happens, great opera means greater

deficits, and when Weber resigned, Fortune Gallo — he

of the itinerant, but financially sound San Carlo Opera — became

manager. And in a move, reminiscent to Mary Garden’s single season,

Martinelli was named Artistic Director.

Then came the Second World War, and for some reason, the conflict

actually seemed to help make people go to the opera even more.

So, after years of struggling night after night with empty seats, the

box office actually had to turn many would-be ticket purchasers away.

Unlike the earlier World War, this time Wagner was not banned. Madame

Butterfly was discreetly left out of plans by management, even though

there was no great clamor to remove it from the public. Stars came,

but often were singing operas between radio broadcasts — a

practice that sometimes resulted in moving the starting time of the performance

to accommodate the singers’ needs to be at the studio for a network hook-up.

In general, even though the company had ‘Chicago’ in its name, it was

nothing like the days when artists were proud to be members of the Chicago

Opera. More reorganizations of the company, and Fausto Cleva became

Artistic Director and, as it had been the case under Gallo, the musical

side was often first rate, but the production and the direction left a

great deal to be desired. As it turned out, Wagner produced the

greatest effect in the last couple of seasons of resident opera before

Lyric. In 1945, despite to few rehearsals and a smallish orchestra

— which caused the withdrawal of George Szell as conductor

— Parsifal turned out to be a triumph, “with all the

essential quality of Wagner’s greatest opera preserved.” The following

season it was Tristan in which, “the music pulsated with exalted

emotion, and the enchantment of the drama held even through the long third

act, which was given uncut.” But few patrons heard this one,

or any of the operas that year, and the deficit for the six weeks was not

paid until 1948 when General Finance Corporation — who,

by that time, owned the building — paid it as an

outright gift. There were plans for a new company, and a few tours

came to Chicago, but after 1946, resident opera ceased in the ‘Windy City’

until 1954.

* * *

* *

Even though it gets a bit depressing towards the end, it should

be obvious that opera in general, and Wagner in particular, often flourished

in Chicago during the first half of the twentieth century. It should

also be obvious that to continue with a lengthy and detailed discussion

of every season would require many pages of text, and result in much necessary

cross-checking to enjoy the details in any kind of systematic order.

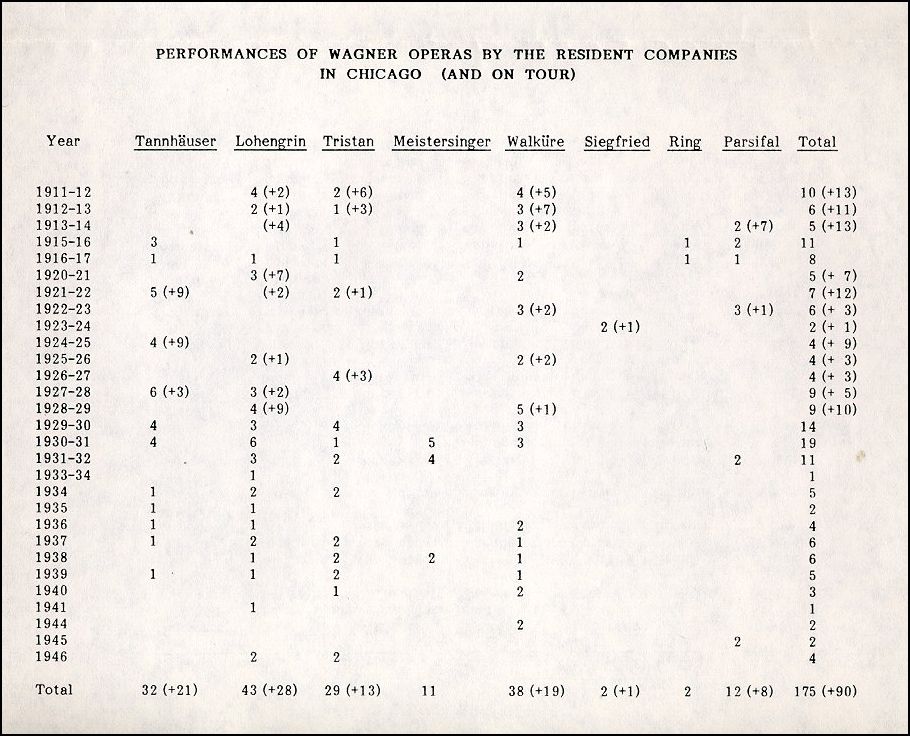

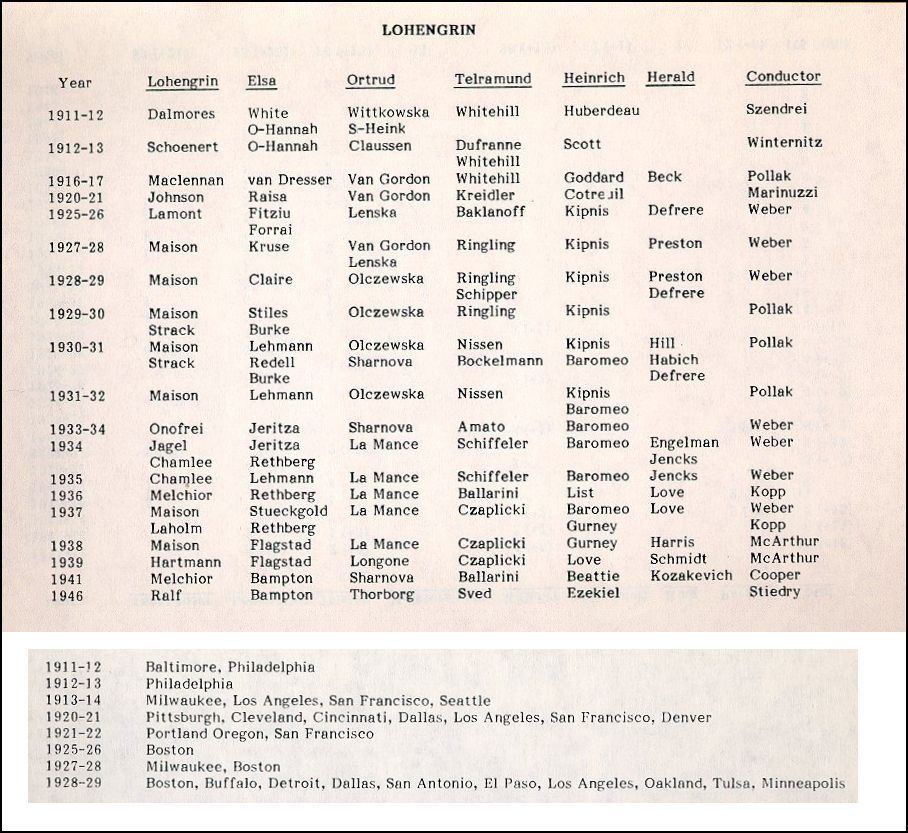

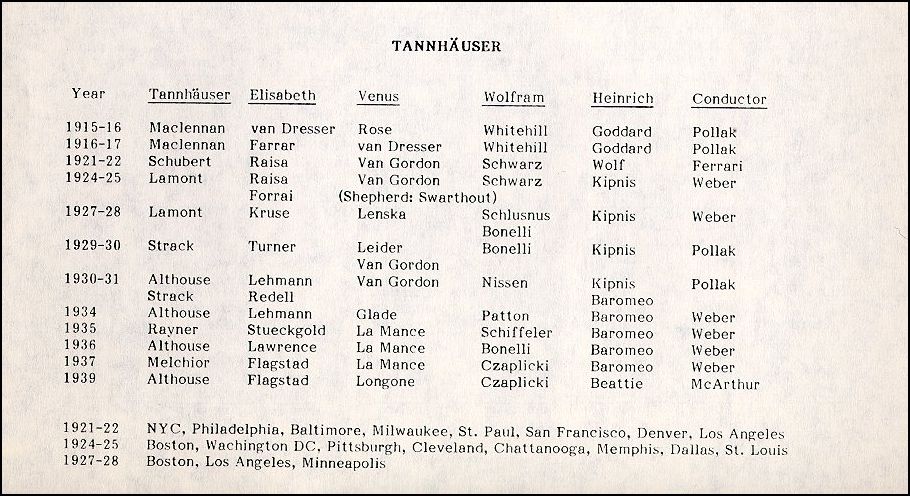

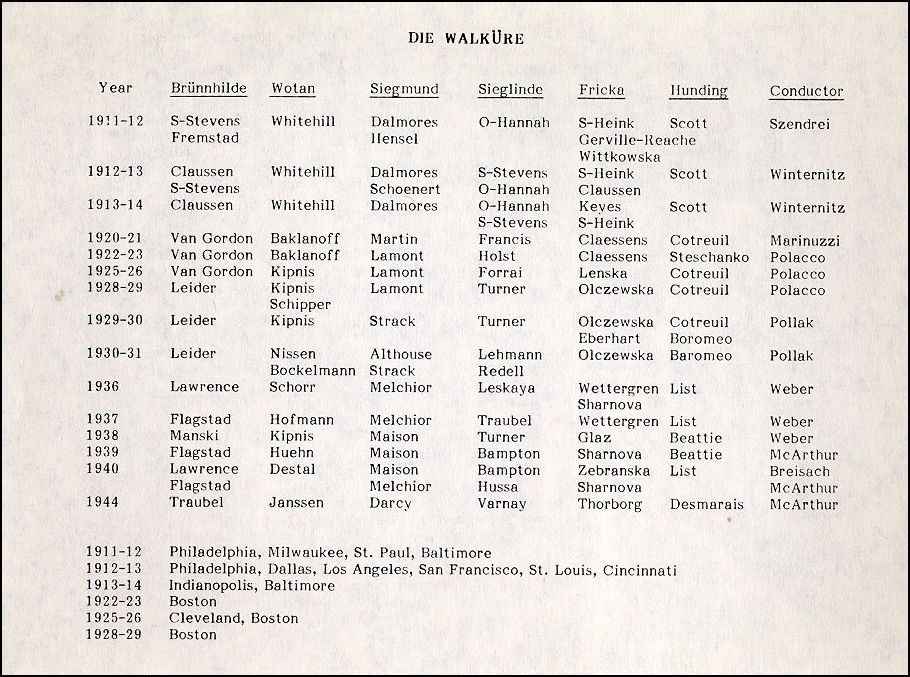

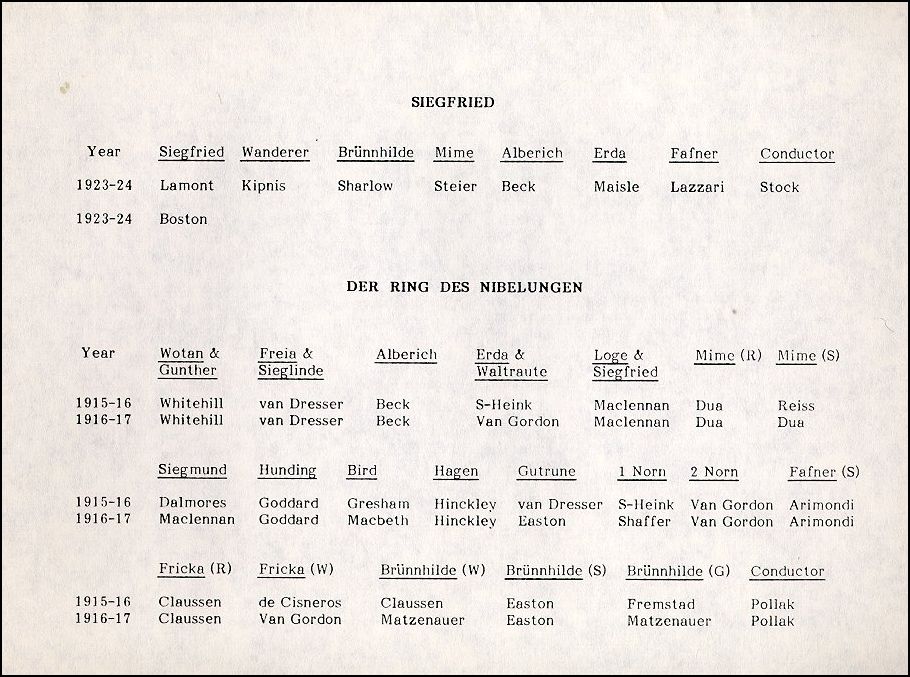

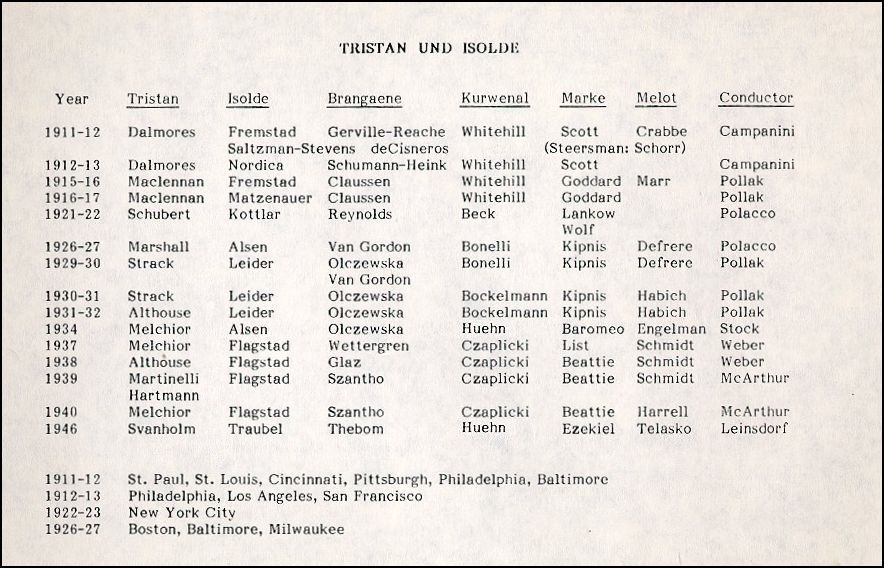

So along with this article are seven pages of charts, detailing all of

the operas and singers for Wagner in Chicago by the resident companies

before Lyric. The first chart gives a listing of all Wagner

operas done by the various companies by year. The number indicated

is the number of performances of that opera in that season, followed by

a number in parentheses which is the number of performances given on tour.

Also on that chart are two sets of totals. The one in the

right-hand column indicates the number of performances of all the Wagner

operas that year. The totals at the bottom of the page are, logically,

the number of times each work was played over the years. But remember,

the Ring adds four operas to the number of performances, but is counted

as a unit at the bottom. So there are four operas in each yearly

total, but only two Rings in the bottom line. Then

there are six pages of operas by season with complete casts. If in

a season a role was sung by two or occasionally three singers, the names

are listed one below the other. Each named singer appeared at least

once in the role, but where there are several performances and only two singers

listed, you will have to consult the annals if you wish to know exactly

who sang with whom. In most instances, however, it should be quite

apparent. At the end of each opera is a second set of year-dates, followed

by a list of American cities. This shows that the opera went on tour

to those cities in that particular year, and the order of the cities is the

order in which the opera was toured. There were, of course, other cities

where other (non-Wagner) operas were given in any year, but again, for that

you must consult the annals. Since the book listing the tour cities

was published in 1930, that is the reason for the abrupt end of the tour

listings. One other note... There were several gala evenings and operatic

concerts, and often an act, or portion of an act, from a Wagner opera was

included. These items, however, are not reflected in the charts.

In every case which I have found, the cast was the same a previous, or later,

performance in that same season.

At first these charts might seem like busy record-keeping nonsense,

but even if only a couple of names are familiar, you’ve got a place to

start. The various repetitions of names give an indication of consistency

and favorable impression upon the audience. Many names are certainly

familiar to every Wagnerian, and lots of them are on the charts, and often

listed several times. One thing that I ran across, which is not reflected

in the charts, is Flagstad / McArthur ‘marathon’

at Thanksgiving, 1939. They came to Chicago for a week, and gave

five performances of four operas. Specifically, it went like this:

November 24th - Tristan; 27th - Tannhäuser; 29th –

Lohengrin; December 1st – Tristan; and 2nd – Die Walküre.

The reasons for this are explained in the interview I did with the conductor.

For me, though, going through this kind of exercise is both joyful

and frustrating — joyful

to see all that was going on in town at that time, and frustrating that

I did not get to any of these wonderful performances! But then the

detective in me starts to hunt around for patterns. Who shows up

where, and is that casting repeated or changed? If you’re like me,

these charts will provide a lot of interesting scanning and hopefully a

lot of titillation.

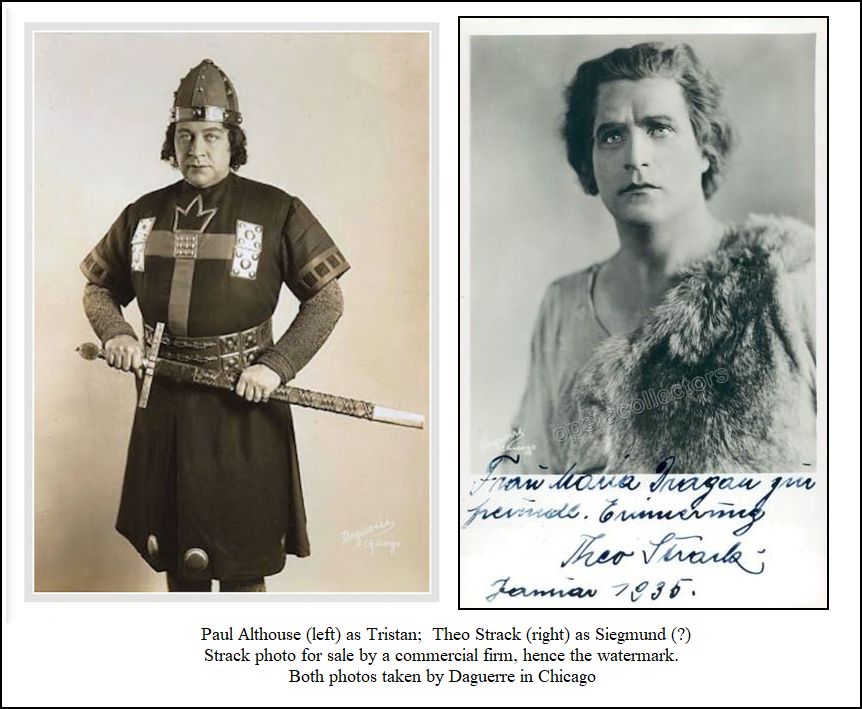

A few notes... For reasons of space, occasionally I’ve had to abbreviate

a couple of names. ‘S-Heink’ is obviously Ernestine Schumann-Heink.

‘S-Stevens’ is Minnie Saltzman-Stevens, a soprano from Bloomington, Illinois,

who made at least a couple of recordings, and ‘O-Hannah’ is Jane Osborn-Hannah,

who also appeared with the company in Butterfly, Natoma

(by Victor Herbert), and Pagliacci. Don’t forget that in

the Walküre chart, two seasons of performances are ‘missing’

because they are included in the Ring chart. And that extra

Walküre performance in 1915-16 had the same cast as in that

season’s Ring. Also, please note that the second entry in

the Siegfried chart is not another year of performances, but the

touring listing. You will also note that in two seasons, 1913-14 and

1921-22, Lohengrin was given on tour but not in Chicago. Since

tour casts were not available to me, one can only guess at the singers who

sang the operas in those years. And as happened in the early days

at the Metropolitan in New York, there were seasons when no opera was given

at all. The years 1914-15, 1932-33, 1943, and the bleak period of

1947-1953 saw no resident opera in Chicago. Then, in 1954, Lyric

Opera was founded (under the name Lyric Theatre, and changed to its present

name two seasons later), and its Wagner repertoire has already been recounted

in previous issues of Wagner News.

* * *

* *

It should be noted that the great Wagner singers also sang also

other operas, and a case in point might be Clarence Whitehill.

Not only was he the sole Heldenbariton from 1911-17

— with the one exception that Hector Dufranne* sang one performance

of Telramund in 1912-13 — Whitehill also

appeared in Hoffman, Madama Butterfly, Königskinder,

and Quo Vadis (by Jean Nouguès) as well as L’Amore dei

Tre Re (by Italo Montemzzi). Charles Dalmorès sang in

just about every opera given during one season or another, as did Dufranne

and Chase Baromeo*. Georges Baklanoff* did a huge variety of roles

in addition to being (according to Musical America) “without doubt

the best Wotan that ever stalked the Auditorium stage.” Another versatile

artist was Alexander Kipnis*. Rosa Raisa** sang a tremendous number

of roles in Chicago in over twenty years with several companies.

She and her husband, Giacomo Rimini, ran a school for singers after their

retirement from the stage. Though she did not sing a lot of Wagner

roles, it was never far from at least one critic’s mind. In Isabeau

by Mascagni, based on the Lady Godiva legend, the famous scene was called

‘The Ride of the Valkyraisa’. One of the most beloved members of

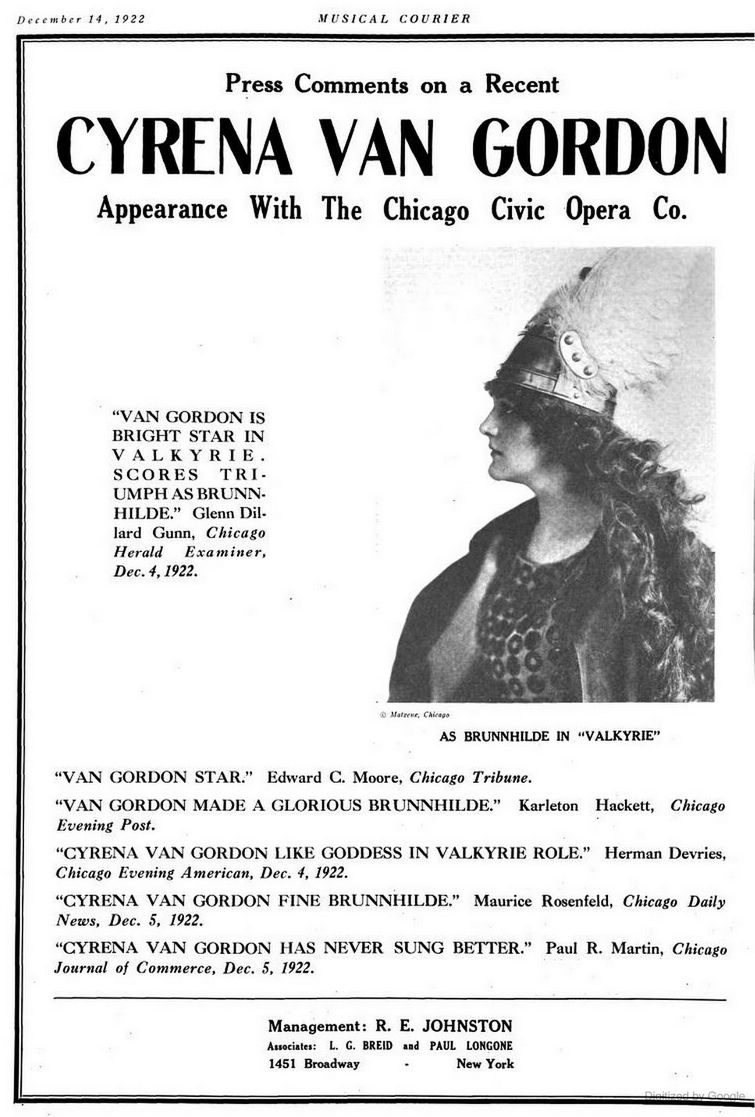

the company was Cyrena van Gordon*. She made her debut as Amneris,

along with Raisa, in 1913, and remained for nearly twenty years, right up

to the demise of the Civic Opera Company in 1932, doing many rules including

Azucena, Laura, Adalgisa (with Raisa), the Witch in Königskinder,

Ulrica, Herodiade (by Massenet), Delilah, as well as appearing in Mefistofele

with both Chaliapin and Kipnis, and in Boris Godunov with Chaliapin,

Baklanoff, and Vanni Marcoux* as the Tsar in various seasons. Her

Wagner repertoire included Ortrud, Venus, Erda, Waltraute, Brangaene, and

Kundry. Then occasionally a name pops up that is completely new, such

a Dimitri Onofrei. A check of the annals for 1933 reveals that not

only did he sing Lohengrin, but he was also heard in Butterfly, Faust,

Carmen, and Tosca. Not bad for a tenor one has not heard

of before or since. Then there was Oscar Colcaire, who sang David

two seasons in a row (as seen in the program at right), and was also

heard as Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly. Please note that Carl

Schiffeler, who sang Wolfram and Telramund in 1935 is not the late, beloved

Paul Schoeffler.

Something else should be pointed out, and that is the list of other

German operas given during this time. Aside from Der Rosenkavalier,

which was heard in five seasons between 1925-30 with Raisa or Leider,

Olczewska and Kipnis, and again in three seasons in the late ’30s

with Lehmann or Hussa** and List, the hit /scandal of the very first

season was Salome with Mary Garden. She sang it twice in

Chicago, and several times on tour that year, and then again in 1921.

The opera was also heard in 1934 with Jeritza**, and in 1940 with Lawrence**,

both of those years with Jagel ** and Sharnova. Hansel and Gretel

was given in several seasons, including 1938 and 1940 with Sharnova as

the Witch. Madama Sharnova, incidentally, lived to be 92, and continued

to teach regularly in Chicago. Several of her students have won

prestigious awards, and others are now themselves vocal teachers.

The year 1916 saw Königskinder with Farrar, Maclennan, Whitehill,

and van Gordon, and the opera with a different cast returned in 1923.

1926 brought Tiefland with Alsen, Lamont* and Kipnis, conducted

by Weber. There was a Fledermaus for December 31st, 1927 with

Raisa, Hackett, Rimini, Baromeo, and Lamont, also conducted by Weber. 1929

saw Fidelio with Leider, Maison*, Ringling*, and Kipnis, conducted

by Pollak. Then in 1931, Mozart came to town with The Magic Flute,

starring Rajdl, Kipnis, Eadie, Marion, Habich, and Dua, and the Three Ladies

were Leider, Votipka and Olczewska! The conductor was Pollak, and

a couple of weeks later he led Mona Lisa with Leider, Bockelmann,

Rajdl, Marion, and Baromeo. One other interesting item was The

Bartered Bride. It was given in two seasons (1930-32) with Rajdl,

Strack, Olczewska, Boromeo, Ringling, Sharnova and Kipnis. Pollak

conducted this Smetana novelty. And that, as the saying goes, was

about all there was of German opera for Chicago by the resident companies

during this period. However, considering all the works which were

presented, audiences were treated to interesting and well-balanced seasons

of opera.

* * *

* *

A few notes on times that items would leap off the page at me

while glancing over the charts. First, Der Fliegende Holländer

somehow never got done in Chicago by the resident companies until Lyric

presented it in 1959. Lohengrin gets the prize for showing

up in the most seasons. And looking at the various interpreters

of the Swan Knight, we have Dalmorès, whom I commented on above,

Francis Maclennan (who sang Parsifal in Savage’s Opera Company on a

US tour in 1904, was the first foreigner to sing Tristan in Germany,

and was married to Florence Easton), Edward Johnson, (who was to run

the Met from 1935-50 after being appointed to the position of Assistant

Manager, and then unexpectedly was almost immediately elevated to the

top spot after the death of Witherspoon), René Maison, Dimitri

Onofrei (who also sang the role at the Met in 1937), Mario Chamlee, Lauritz

Melchoir, Carl Hartmann, and Torstan Ralf. Quite an assortment

of weights, personalities and nationalities! The same can be said

of the various Elsas. Rosa Raisa shows up in 1920, Lotte Lehmann

in three seasons, Maria Jeritza in two, plus the usual assortment who

also appeared in the role. Ditto for Ortrud. Note that Pasquale

Amato once did Telramund. In Tannhäuser, notice that

Heinrich Schlusnus turns up as Wolfram, and Gladys Swarthout once was the

Shepherd. All the critics loved her and predicted great things for

her career. Mary Garden adroitly said that she would be the next

Carmen. Leider sang Venus (surprisingly), and Eva Turner was Elisabeth.

William Beck*, the resident Alberich and Klingsor (who was found poisoned

in his hotel on an evening he was to have sung), turned up in 1924-25

as Biterolf. Howard Preston sang it the next time Tannhäuser

was presented. [More on this Beck story is, again, on the Massenet

webpage.] When you look at the Tristan chart, hold it

away from your eyes just a bit and see the names as they appear in blocks.

This seems to be the most consistently cast work from year to year.

Friedrich Schorr did the very small role of the Steersman early in his

career, and Armand Crabbé* turns up as Melot, as does Mack Harrell.

In the Ring, and specifically Die Walküre, notice

that van Gordon, who also did Venus, and Ortrud, and Brangäne, does

Brünnhilde. Minnie Saltzman-Stevens moves from Brünnhilde

to Sieglinde, the reverse of the norm for a soprano. Also note that

Julia Claussen* sings Brünnhilde and Fricka. (Yes, I double-checked

that one!) And not only did the company give Siegfried alone

in 1923-24, but it went out on tour. Apparently though, Stock cut about

an hour out of the score. Sharlow*, who sang Brünnhilde, was

very familiar to Chicago audiences as Micaëla in Carmen. Earlier

I called attention to the spirit of the company, and that is perhaps best

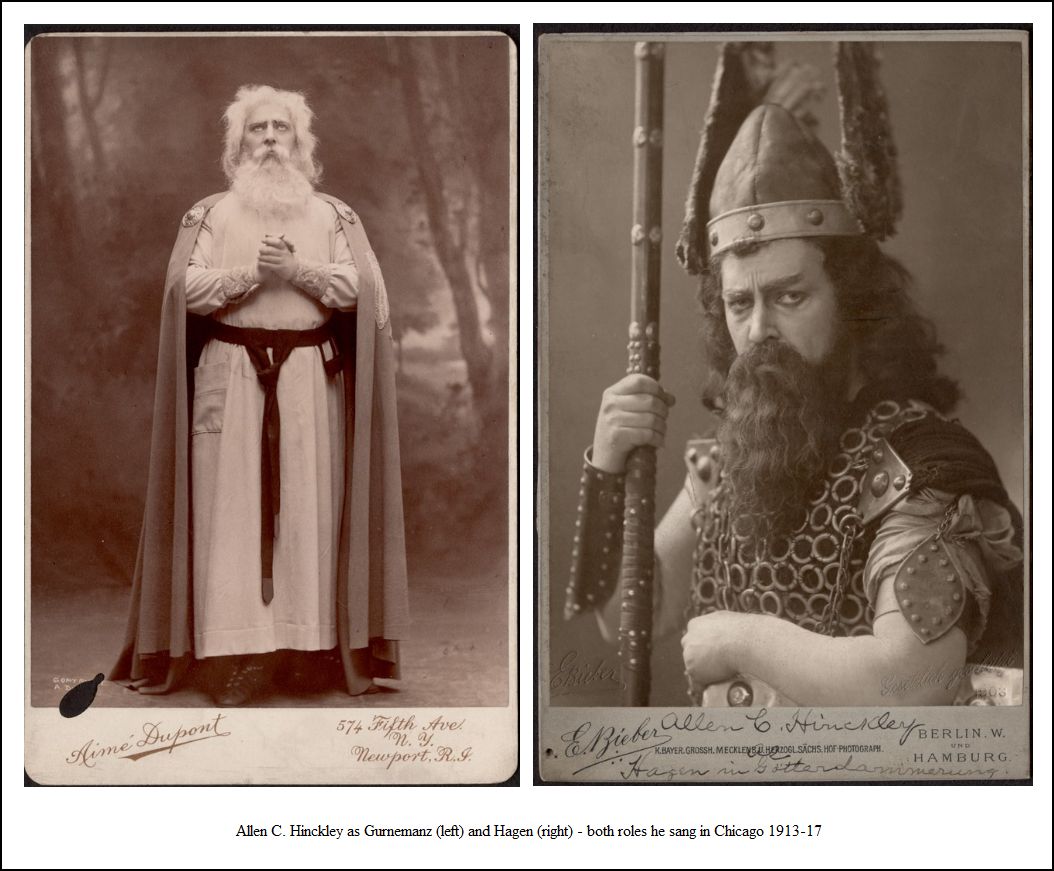

illustrated in many smaller roles, such as the Valkyries. In the late

1920s, Maria Claessens*, who had sung many roles with the company, including

Fricka, was Waltraute. Coe Glade*, who later would be a famous Carmen,

Mignon and Adalgisa, sang Rossweisse. And in 1930-31, Jennie Tourel

appeared as Siegrune.

Just for the record, there were a few performances of Wagner operas

given by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Naturally, Wagner played

a huge part in their programs right from the start, but on occasion there

were complete operas, and once a single act. To wit, and in order

of their presentation, in November of 1935 there were four concert performances

of Tristan with Dorothy Manski, Melchoir, Kathryn Meisle, Fred

Patton, Baromeo and Preston, conducted by Stock. But the interesting

thing was that the series happened Thursday evening, Friday afternoon, Monday

evening and Tuesday afternoon. Next, in January of 1946, Désiré

Defauw presented a program of Music from the four Ring dramas

— orchestral music from Götterdämmerung, Siegfried,

and Rheingold (in that order), then, after the intermission the complete

first act of Die Walküre with Astrid Varnay, Emery Darcy and

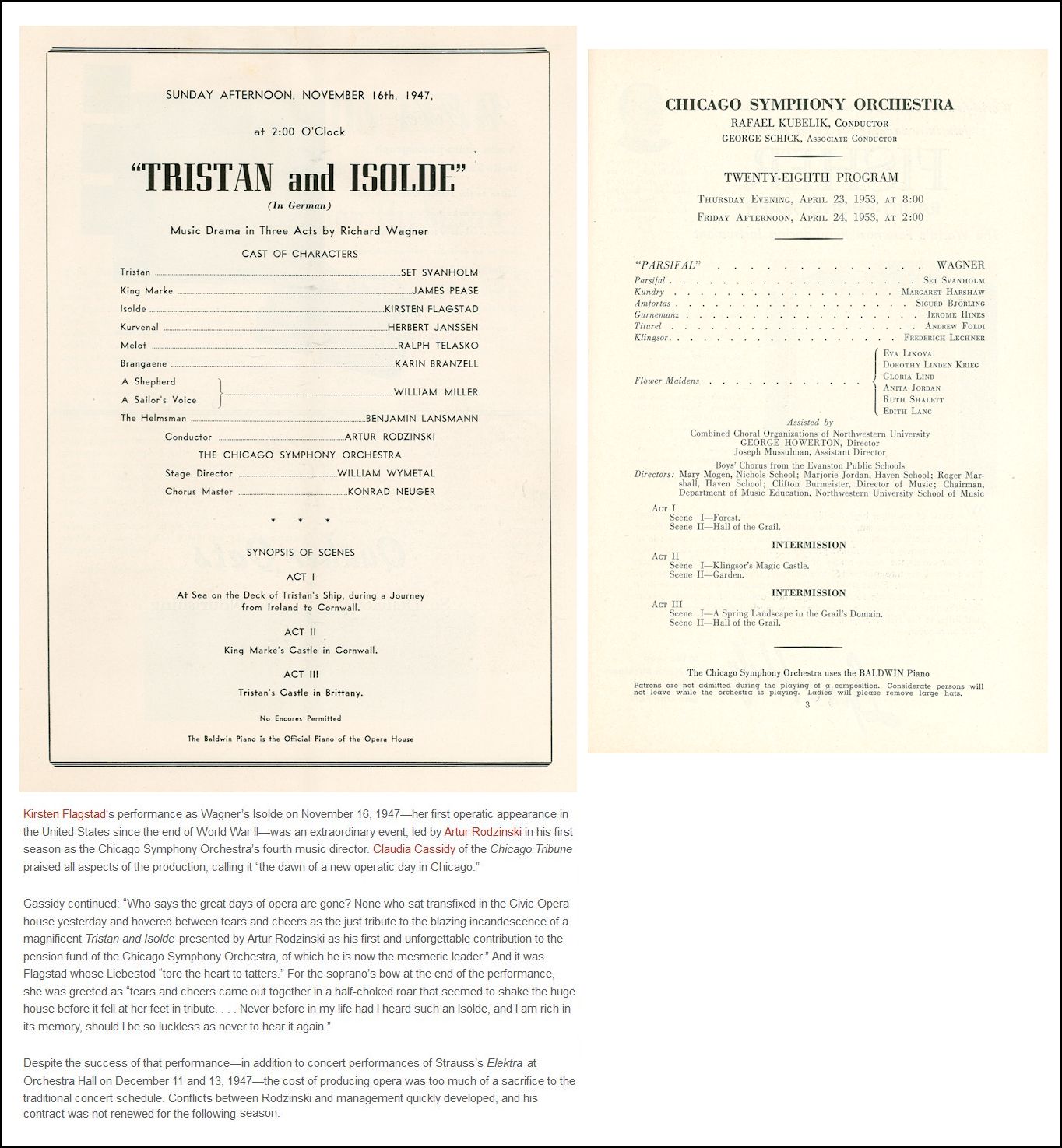

James Pease. Then came the Pension Fund Concert of November 16th,

1947 — a complete Tristan performed at the

Opera House, with Flagstad, Set Svanholm, Karin Branzell, Herbert Janssen

and Pease, conducted by Artur Rodzinski. Musical America said,

“It was as though the fabulous days of Chicago’s operatic past had returned.”

Finally, the famous Rafael Kubelik Parsifal in April of 1953.

The cast had Svanholm, Margaret

Harshaw, Sigurd Björling, Jerome Hines, Andrew Foldi

and Frederick Lechner. The chorus, before Margaret Hillis, came

from Northwestern University and the Evanston Public Schools. That

is all in the era being considered in this survey, namely pre-Lyric. In

case you hadn’t guessed already, it really boggles the mind

— at least my mind.

* * *

* *

Much of the material in this report, especially the charts, was

gathered from two very important books. The first is Opera

in Chicago by Ronald L Davis. His volume, like this report,

is in two sections. The first is a narrative about the opera in

Chicago from the earliest days up through the end of 1965. Then

there is a comprehensive listing of every performance by the resident

companies from the first season (1910-11) through the fall Lyric season

of 1965. The other book is Edward C Moore’s work entitled Forty

Years of Opera in Chicago. That volume deals with opera in the

‘Windy City’ up through the move to the new house in 1929. While

not giving any but a very few isolated cast lists, there is a full listing

at the end telling which opera was given on which date in every village

and hamlet that the Chicago opera companies visited.

It was also my very great fortune a few years ago to have the opportunity

to purchase a collection of programs from the Chicago opera companies

for the years 1922-37. Not only was the collector of this treasure

a saver of programs, but with each playbill are pictures and reviews from

several of the day’s newspapers. This is truly a fascinating look

at the opera and its importance as seen and heard through the eyes and

ears of those present at the time. I am also grateful to Jerry Zimmerman,

the editor of Wagner News, for tracking down those last few pesky

facts and isolated names to fill in the remaining gaps in the charts,

and for encouraging my progress as this report grew to Wagnerian proportions.

* * *

* *

Bruce Duffie is an announcer for radio station WNIB-FM, Classical

97 in Chicago. He has given lectures on opera for Lyric Opera of

Chicago, and his interviews with leading operatic artists have appeared

on WNIB, in the Journal of the Massenet Society, Opera Scene

– of which he was the editor – Nit & Wit Magazine, and in many

previous issues of Wagner News.

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This article was published in Wagner News in March, 1985.

This edition was made in 2018, and posted on this website at

that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry

for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here.

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with

WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment

as a classical station in February of 2001.

His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series

on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You

are invited to visit his website for more information

about his work, including selected transcripts

of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests.

He would also like to call your attention to the photos

and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.