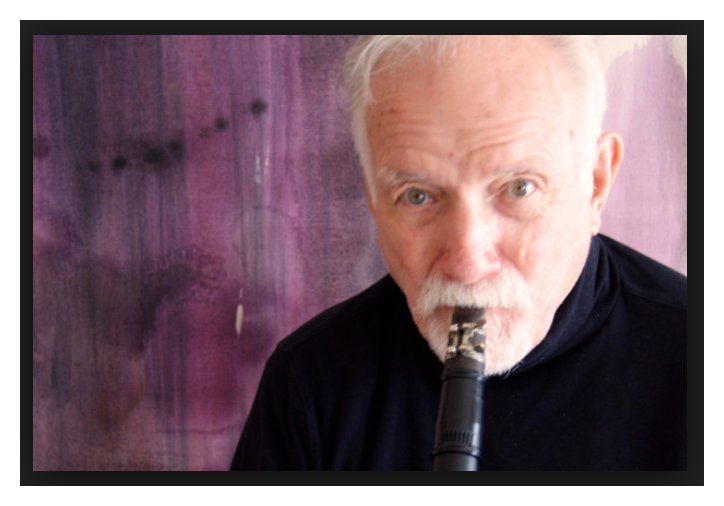

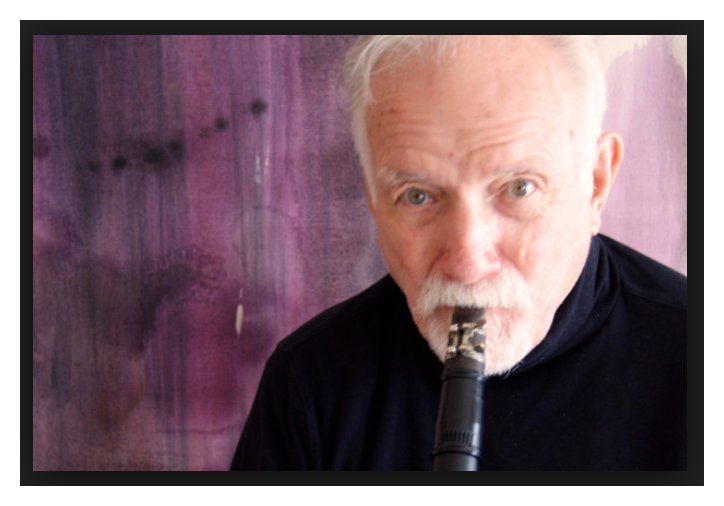

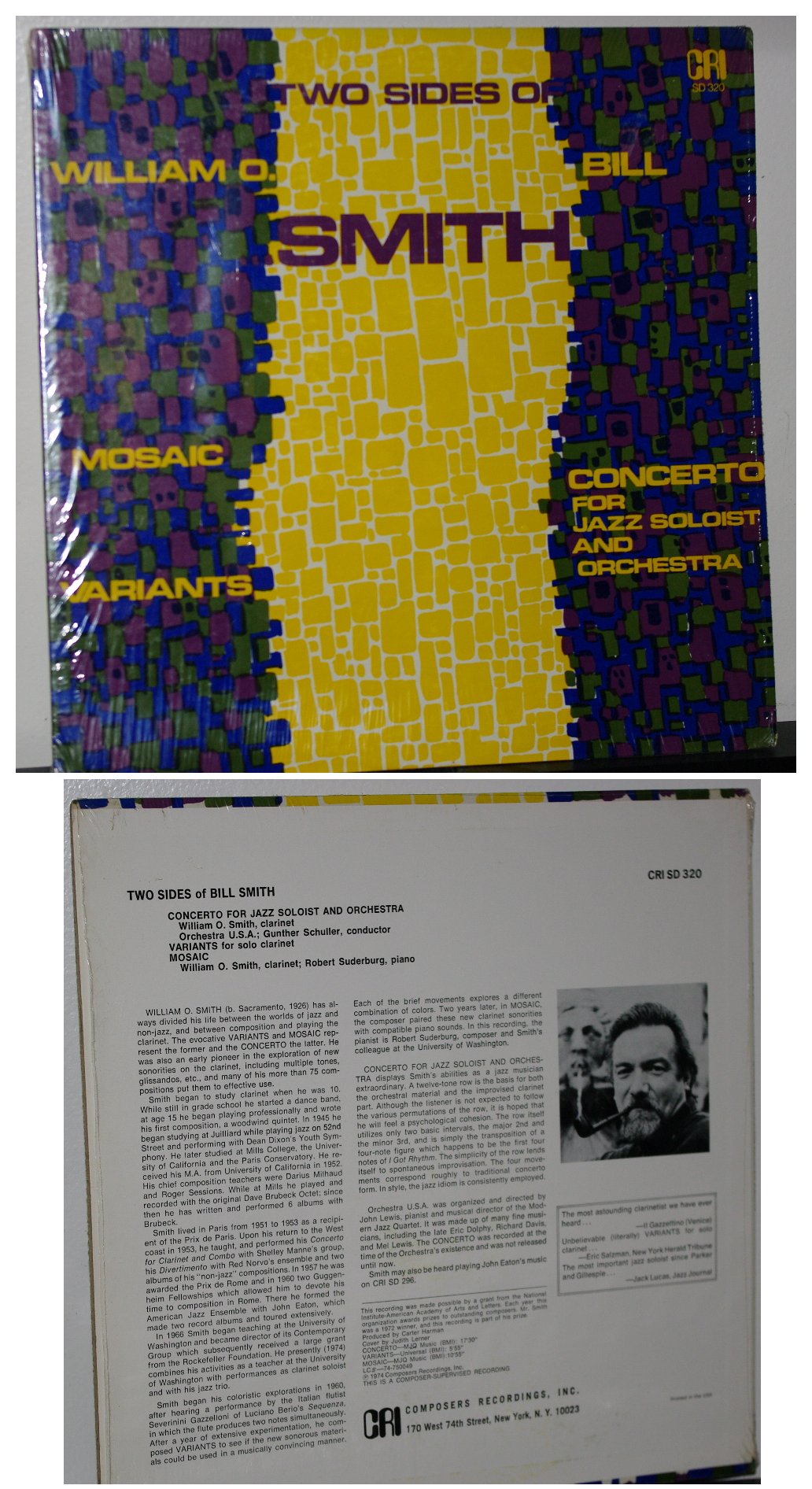

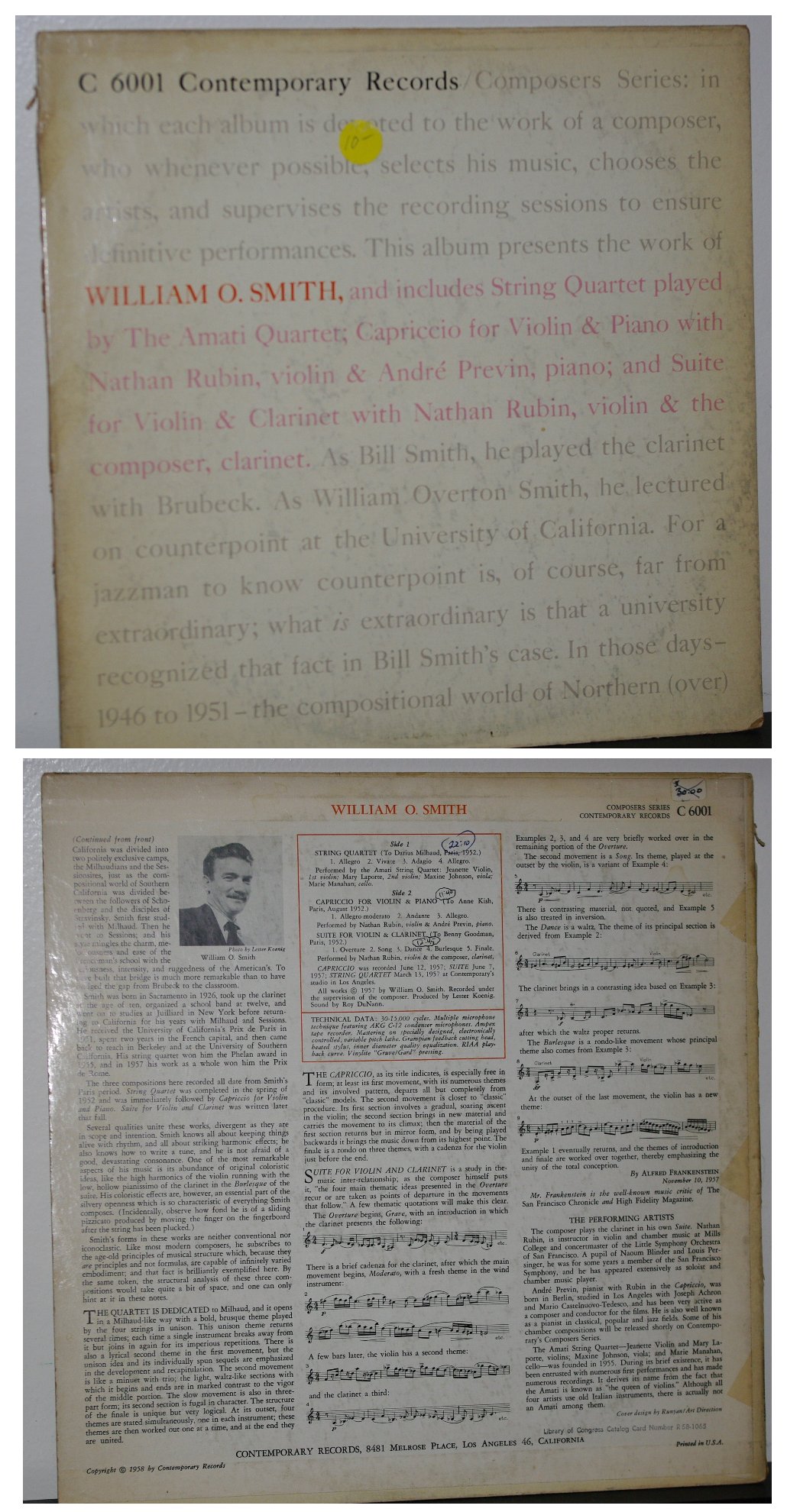

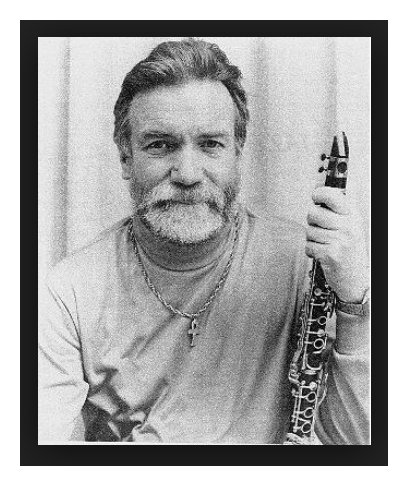

WILLIAM O. SMITH - Philip Rehfeldt, New Directions for Clarinet, Revised Edition (1994) Born in Sacramento, California, in 1926, William O. Smith began playing the clarinet at the age of ten. In his teens, he initiated the dual life that he has followed ever since: leading a jazz orchestra while also performing with the Oakland Symphony. After high school and a year "on the road" traveling with various bands, he attended Juilliard during the day while playing jazz clubs at night. Smith studied composition with Darius Milhaud at Mills College in 1946 and with Roger Sessions at the University of California at Berkeley, receiving B.A. and M.A degrees from that school in 1950 and 1952. He also attended classes at the Paris Conservatory (1952-53) and the Juilliard Institute (1957-58). His awards include a Prix de Paris, the Phelan Award, a Prix de Rome, A Fromm Players Fellowship, a National Academy of Arts and Letters Award, a BMI Jazz Pioneer Award, and two Guggenheims. He taught at the University of California, Berkeley, the San Francisco Conservatory, and the University of Southern California. Since 1966, he has been the director of the Contemporary Group at the University ot Washington. His association with Dave Brubeck began at Mills College, where he was one of the founders of the Dave Brubeck Octet and responsible for many of the group's arrangements. His SCHIZOPHRENIC SCHERZO, written for the Octet in 1947, was one of the first successful integrations of modern jazz and classical procedures, a style which later became known as "third stream." His work with Brubeck and others in this direction can be heard on a number of recordings. In the early 1960s, he was also among the earliest performers to experiment with new color resources for the clarinet, this after listening to Severino Gazzeloni's similar work on the flute. His DUO FOR FLUTE AND CLARINET (1961) used these techniques, the multiple sonorities very likely being the first of their type to be precisely notated. He was also responsible for a number of other works using these sonorities, including John Eaton's CONCERT MUSIC FOR SOLO CLARINET (recorded on CRI 296), Gunther Schuller's EPISODES, Larry Austin's CURRENT FOR CLARINET AND PIANO, William Bergsma's ILLEGIBLE CANONS (recorded on MHS 3533), Pauline Oliveros' THE WHEEL OF FORTUNE - a theatre piece based on Smith's astrological chart - and Luigi Nono's A FLORESTA (recorded on Arcophon AC 6811). About VARIANTS FOR SOLO CLARINET (1963), Eric Salzman wrote in the New York Herald Tribune on March 14, 1964, "William Smith's clarinet pieces, played by himself, must be heard to believe - double, even triple stops; pure whistling harmonics; tremolo growls and burbles; ghosts of tones, shrill screams of sounds, weird echoes, whispers and clarinet twitches; the thinnest of thin, pure lines; then veritable avalanches of bubbling, burbling sound. Completely impossible except that it happened." -- Names throughout this webpage

which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD

|

WOS: It is the actual score they read from.

In performance the score will be projected on a nine-foot by twelve-foot screen

that is a blow-up of the computer monitor that I’m realizing the graphics

on. This is the fourth piece I’ve done. They’re not electronic

music, but they’re using the possibilities of letting the computer sort out

the difficulties and rhythmic complications. One piece I did several

years ago for the Kronos Quartet, which was called Kronos, involved four different tempos

simultaneously. They were in a proportion, always, of four to five

to six to seven, or to put it another way, the quarter note of the cello

equaled 80, the viola equaled 100, the second violin was 120, and the first

violin was 140. With the computer, that’s easy to realize. Your

music is just flowing by, and when it hits the trigger line you play at that

moment. Then it doesn’t matter that these are complicated things intellectually.

It doesn’t matter to the computer, and the musician doesn’t have to be bothered

with it, either. He just plays his note at his trigger line.

In other words, it’s like what happens if you’re playing an audio tape.

The note sounds when it goes by the read head. It plays at that moment,

and this is just the same visually. When the note reaches the line

indicating play, you play, and you stop when it leaves. Anyway, it

seems to me it’s a way of exploring what would be very complicated rhythmic

combinations in a way that is practical.

WOS: It is the actual score they read from.

In performance the score will be projected on a nine-foot by twelve-foot screen

that is a blow-up of the computer monitor that I’m realizing the graphics

on. This is the fourth piece I’ve done. They’re not electronic

music, but they’re using the possibilities of letting the computer sort out

the difficulties and rhythmic complications. One piece I did several

years ago for the Kronos Quartet, which was called Kronos, involved four different tempos

simultaneously. They were in a proportion, always, of four to five

to six to seven, or to put it another way, the quarter note of the cello

equaled 80, the viola equaled 100, the second violin was 120, and the first

violin was 140. With the computer, that’s easy to realize. Your

music is just flowing by, and when it hits the trigger line you play at that

moment. Then it doesn’t matter that these are complicated things intellectually.

It doesn’t matter to the computer, and the musician doesn’t have to be bothered

with it, either. He just plays his note at his trigger line.

In other words, it’s like what happens if you’re playing an audio tape.

The note sounds when it goes by the read head. It plays at that moment,

and this is just the same visually. When the note reaches the line

indicating play, you play, and you stop when it leaves. Anyway, it

seems to me it’s a way of exploring what would be very complicated rhythmic

combinations in a way that is practical. WOS: I think so. I don’t know. It’s

hard in the abstract to deal with that one. Sometimes I will start

out a piece and not know where it’s going to take me, and will end up in

places I hadn’t expected to get to. But more often than not, when I

start a piece I have a general idea about it. It becomes more specific

as I progress. I’m sure this present piece I’m doing for woodwind quintet

using computer graphics will end me up in some unexpected places because

I’m working with techniques that are new to me. In fact, it’s a little

bit scary. I have to think “dare” because of what I can get the computer

to do. I’m not completely sure of it all, and I have to work it out

bit by bit and say, “Well, okay. I see now I can do this. If

I want to do this, I could do it but it won’t be practical; this I can’t

do.” It’s a lot different from doing something in completely conventional

circumstances where you know what all the parameters are. There are

lots of question marks left with what I’m working with now.

WOS: I think so. I don’t know. It’s

hard in the abstract to deal with that one. Sometimes I will start

out a piece and not know where it’s going to take me, and will end up in

places I hadn’t expected to get to. But more often than not, when I

start a piece I have a general idea about it. It becomes more specific

as I progress. I’m sure this present piece I’m doing for woodwind quintet

using computer graphics will end me up in some unexpected places because

I’m working with techniques that are new to me. In fact, it’s a little

bit scary. I have to think “dare” because of what I can get the computer

to do. I’m not completely sure of it all, and I have to work it out

bit by bit and say, “Well, okay. I see now I can do this. If

I want to do this, I could do it but it won’t be practical; this I can’t

do.” It’s a lot different from doing something in completely conventional

circumstances where you know what all the parameters are. There are

lots of question marks left with what I’m working with now. BD: Are the pieces you write on commission, or are

they just things you have to get out of your system?

BD: Are the pieces you write on commission, or are

they just things you have to get out of your system?

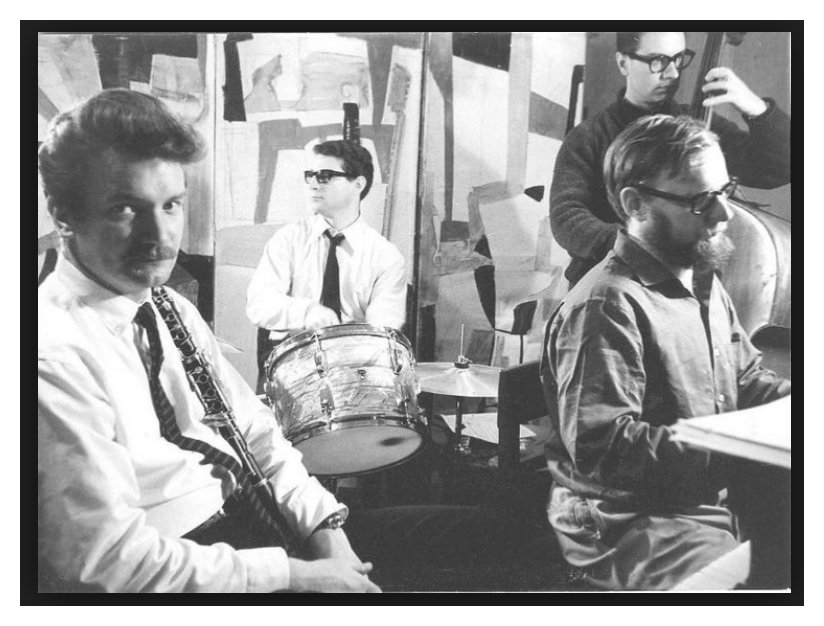

| [From a blog by Astronauta Pinguim

posted Tuesday, June 26, 2012, with an interview of composer John Eaton] ASTRONAUTA - The jazz musician Bill Smith was a great friend of yours and one of the first persons you met when you moved to Italy in the late '50s/early 60's. Could you tell us a little about the period you played with him? Is there any record/film/photograph of that time? [Photo below shows Smith with his clarinet on the left and Eaton on the right at the piano.] JOHN EATON - Bill (William O. Smith) was not a pianist, but a magnificent - the best in my opinion! - jazz and classical clarinetist. We had a group in Rome that toured Europe and the USA doing concerts of contemporary music, jazz, and especially, both on the same program. We met the fall of 1960 and immediately began performing written compositions, jazz and other music together around Italy, and then for Columbia Artists in the USA. We recorded 2 jazz albums, one for RCA Victor, New Sounds: Old World with Erich Peter and Pierre Favre, and one for Epic, New Dimensions with Richard Davis and Paul Motion.

|

WOS: The technical achievement is in the basic learning

of grammar. If you want to be a poet, you first learn traditional grammar

and literature and Shakespeare, etcetera. I would think that you would

want to know what went before you, and be able to construct sentences and

essays in terms of conventions that make sense. After you can do that

you can handle things more freely and in a more individualized manner.

In the advanced things your teacher is just more of a guide than someone

who is giving you rules and regulations to work by. It’s the same in

painting as in musical composition. You start out and learn strict

counterpoint and Bach counterpoint and nineteenth century harmony, then traditional

orchestration. All these things strengthen you, but in the long run

you try and find your own path, and in finding your own path, the best you

can hope for is gentle guidance.

WOS: The technical achievement is in the basic learning

of grammar. If you want to be a poet, you first learn traditional grammar

and literature and Shakespeare, etcetera. I would think that you would

want to know what went before you, and be able to construct sentences and

essays in terms of conventions that make sense. After you can do that

you can handle things more freely and in a more individualized manner.

In the advanced things your teacher is just more of a guide than someone

who is giving you rules and regulations to work by. It’s the same in

painting as in musical composition. You start out and learn strict

counterpoint and Bach counterpoint and nineteenth century harmony, then traditional

orchestration. All these things strengthen you, but in the long run

you try and find your own path, and in finding your own path, the best you

can hope for is gentle guidance.

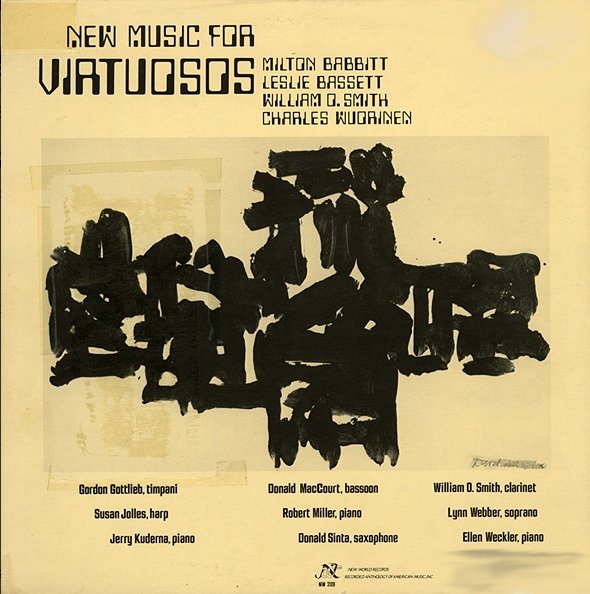

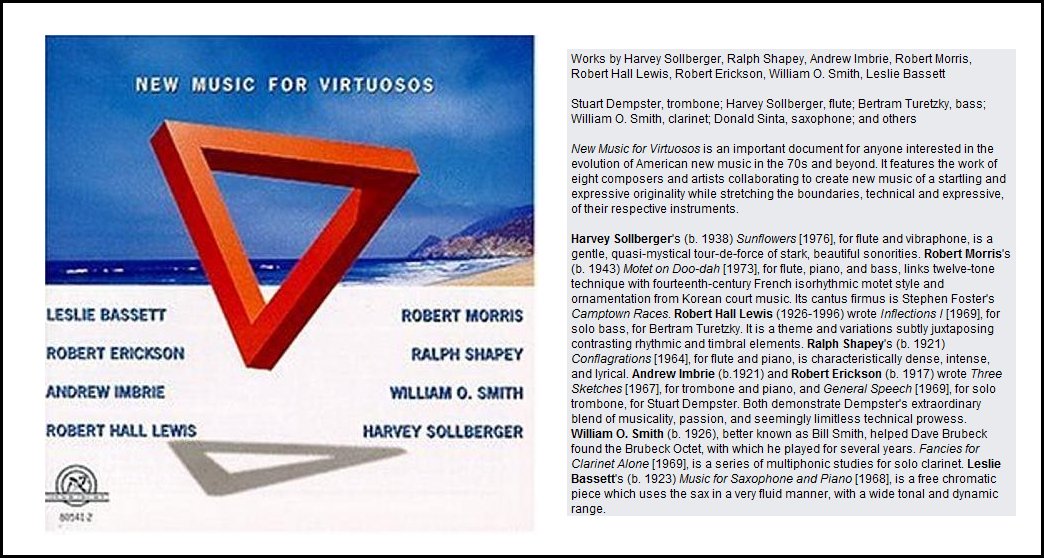

The original LP of "New Music for Virtuosos" at left. A second LP was issued soon thereafter. The CD shown below is a compilation of much (but not all) of the material on the two LPs. Some of my other guests who are composers and/or performers on these recordings... See my Interview with Milton Babbitt. See my Interview with Leslie Bassett. See my Interview with Charles Wuorinen. See my Interview with Robert Erickson. See my Interview with Andrew Imbrie. See my Interview with Robert Hall Lewis. See my Interview with Ralph Shapey. See my Interview with Harvey Sollberger. See my Interview with Bertram Turetzky.

|

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Seattle, Washington, on July 31,

1987. Portions were broadcast (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1991

and 1996. This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.