A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

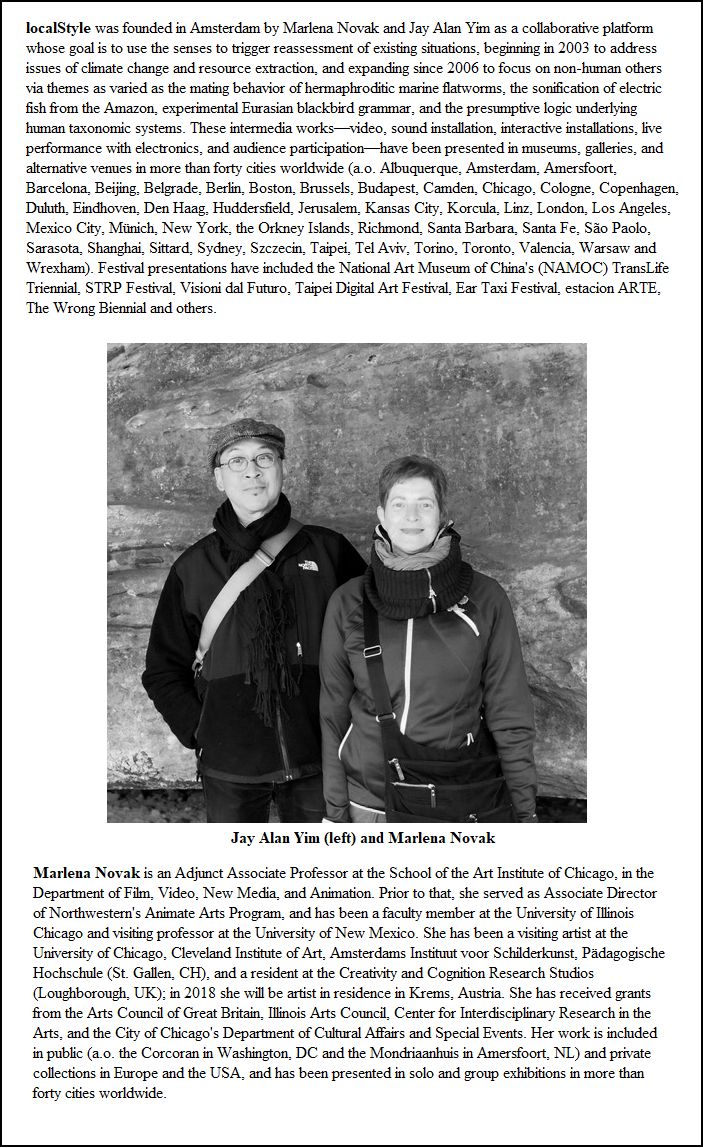

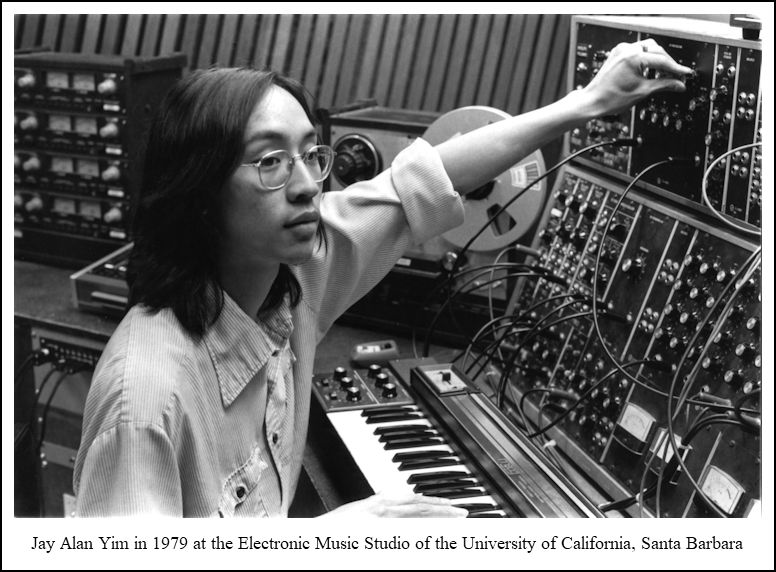

Jay Alan Yim studied music composition at the University of California Santa Barbara, the Royal College of Music, and Harvard, and computer music at MIT and Stanford. He currently teaches at Northwestern University. He has received Guggenheim, National Endowment for the Arts, and three Illinois Arts Council fellowships, and many other awards. His music has been featured at international festivals (a.o. Darmstadt, Ars Musica, Wien-Modern, Gaudeamus, Tanglewood, Aspen, ISCM World Music Days) and has been performed by the New York Philharmonic, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Orchestre National de Lyon, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, Nederlands Radio Filharmonisch Orkest, Residentie Orkest Den Haag, Sendai Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic New Music Group, London Sinfonietta, Arditti Quartet, JACK Quartet, Spektral Quartet, Andiamo String Quartet, Nieuw Ensemble, Ensemble SurPlus, dal niente, ICE, Frances-Marie Uitti, Gareth Davis, Laura Chislett, Harrie Starreveld, Dalia Chin and many others. In 2000, he co-founded the collaborative localStyle with Marlena Novak. Using high and low tech means, their intermedia practice includes video, interactive installations, live performance with electronics, and audience participation. They created localStyle as a collaborative platform whose goal is to use the senses to interrogate existing situations, beginning in 2003 to address issues of climate change and resource extraction, and expanding since 2006 to focus on non-human others via themes as varied as the mating behavior of hermaphroditic marine flatworms, the sonification of electric fish from the Amazon, experimental Eurasian blackbird grammar, the presumptive logic underlying human taxonomic systems, singing coral reefs as the Voice of the Anthropocene, and bootstrapping agriculture on Mars. These works have been presented in festivals, museums, galleries, and alternative venues in more than forty cities worldwide (a.o. Albuquerque, Amsterdam, Amersfoort, Barcelona, Beijing, Belgrade, Berlin, Boston, Brussels, Budapest, Camden, Chicago, Cologne, Copenhagen, Duluth, Eindhoven, Den Haag, Huddersfield, Jerusalem, Kansas City, Korcula, Linz, London, Los Angeles, Mexico City, Münich, New York, the Orkney Islands, Richmond, Santa Barbara, Santa Fe, São Paolo, Sarasota, Shanghai, Sittard, Sydney, Szczecin, Taipei, Tel Aviv, Torino, Toronto, Valencia, Warsaw and Wrexham). Festival presentations have included the National Art Museum of China’s (NAMOC) TransLife Triennial, STRP Festival [scale (in collaboration with neuromechanical engineer Malcolm MacIver)], Visioni dal Futuro, Taipei Digital Art Festival, Ear Taxi Festival, estacion ARTE, The Wrong Biennial and others. |

© 2006 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Evanston, Illinois on May 23, 2006. Portions were broadcast on WNUR in 2010, and 2018. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.