|

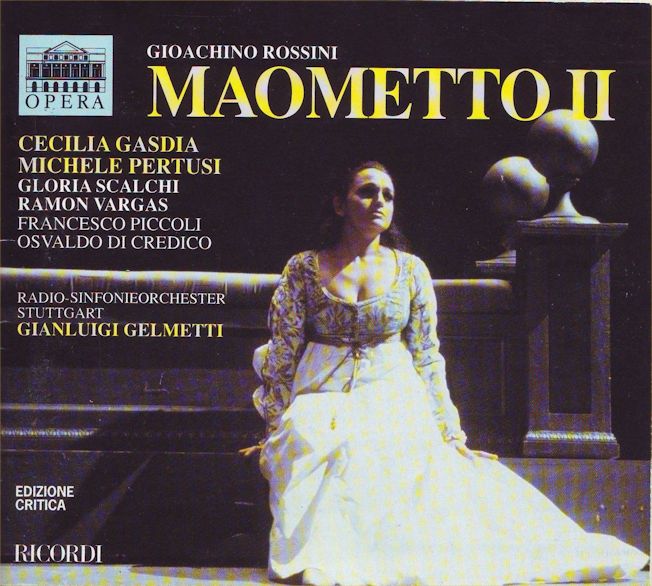

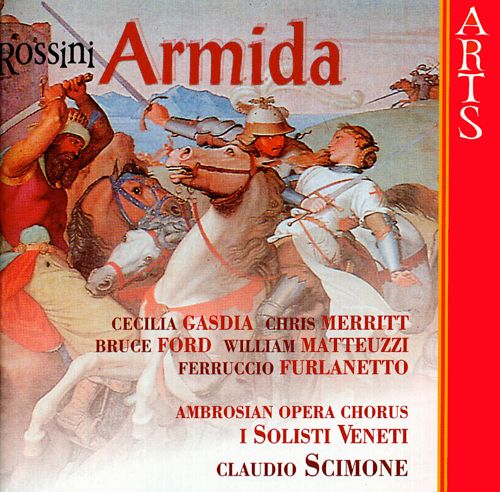

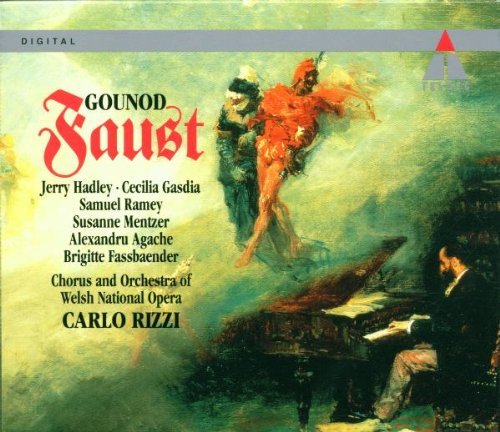

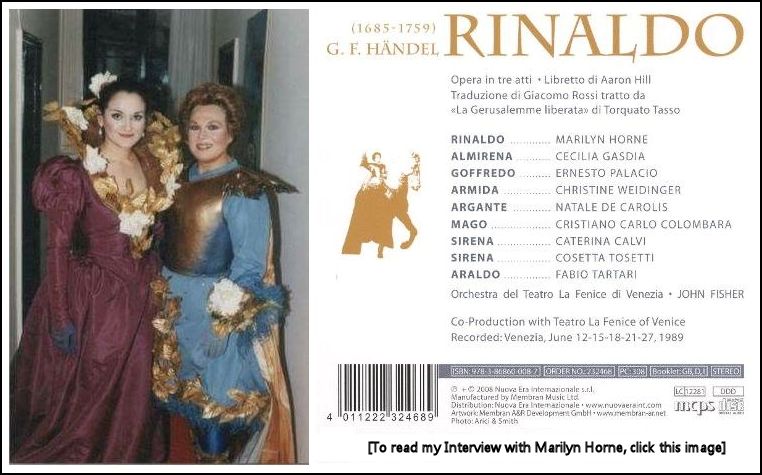

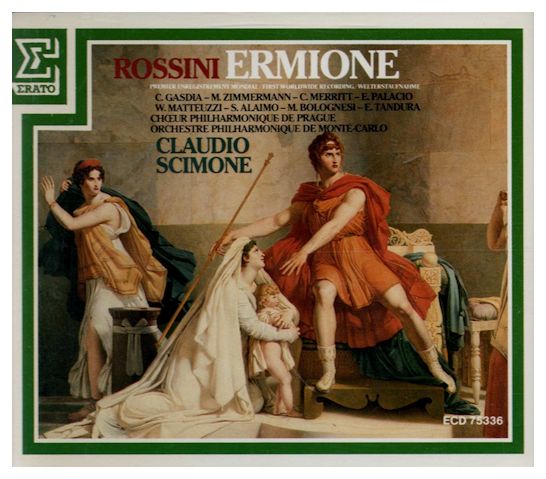

Cecilia Gasdia is one of the most internationally appreciated singers of Rossini’s work, and her repertoire includes fourteen of his roles. The collaboration with the Rossini Festival in Pesaro, which began in 1983 with Mosè in Egitto, has continued over the years with Le Comte Ory, Il Viaggio a Reims conducted by Claudio Abbado of which a highly successful record was made by DG, Maometto II, Otello and Semiramide. In June 1994, Gasdia took part in an extraordinary concert in

the Sarajevo National Library conducted by Zubin Mehta, performing Mozart’s

Requiem alongside José Carreras and Ruggero Raimondi. The

concert, dedicated to the victims of the tragedy of ex-Yugoslavia, was

broadcast by more than 30 television networks all round the world. Among her most important engagements of the 1997-98 season were

the productions of Orfeo by Monteverdi at the Athens Concert Hall,

staged by Pier Luigi Pizzi and conducted by Claudio Scimone, Un giorno

di regno by Verdi at the Teatro Regio in Parma, Orfeo in a

production of the Teatro Comunale in Florence, Giulio Cesare by

Handel at the Teatro dell’Opera in Rome, and L’Amico Fritz by Mascagni

at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples. During the season 1998-99 she was busy with productions of Il barbiere di Siviglia at the New National Theater Tokyo, L’Amico Fritz at the Teatro Bellini in Catania, a series of concerts with Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater in Genoa and other Ligurian theaters, a long series of concerts all over Italy with Claudio Scimone and I Solisti Veneti, a production of Orfeo by A. Sartorio at the Teatro in Fano/Italy conducted by Alberto Zedda, and The Merry Widow at the Arena of Verona. Among her most important engagements of the 2000 season were

the productions of Pagliacci by Leoncavallo at the Teatro Bellini

in Catania conducted by Daniel Oren, Le Jongleur de Notre Dame by

Massenet conducted by Gelmetti at the Teatro dell’Opera in Rome, and Mosè

in Egitto by Rossini under the direction of Pier Luigi Pizzi and

conducted by Claudio Scimone at the Teatro Filarmonico in Verona. In January 2001 she had a personal success in L’Amico Fritz

with Andrea Bocelli at the Teatro Filarmonico in Verona (shown in

photo below). In March-April she joined Bocelli on US Spring Tour of

eight concerts in USA and Canada, and in June she appeared in a Gala Concert

with Bocelli in Pisa for the reopening of the Tower of Pisa.

In February and March 2002 Gasdia sang Pagliacci by Leoncavallo at the Teatro Filarmonico-Arena of Verona Foundation and in April 2002 she debuted as Tosca by Puccini at the Opera Theater in Cairo. During 2003 she sings for Fondazione Gulbekian in Lisbon, and she

is the artistic witness in the world for the 25th Anniversary of the

Pontificate of John Paul II singing in Rome, Strasbourg, Monaco di Baviera,

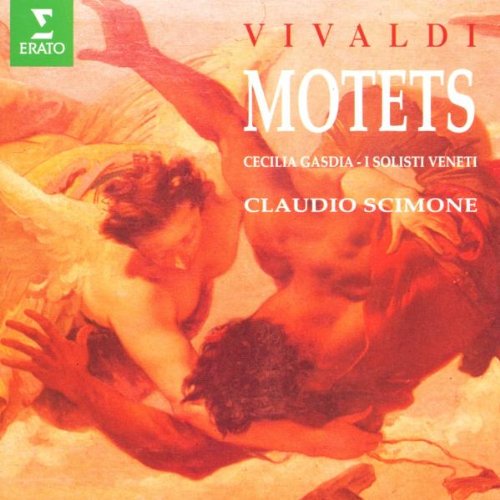

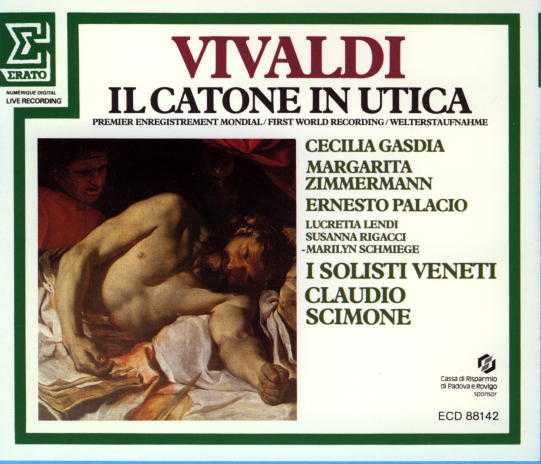

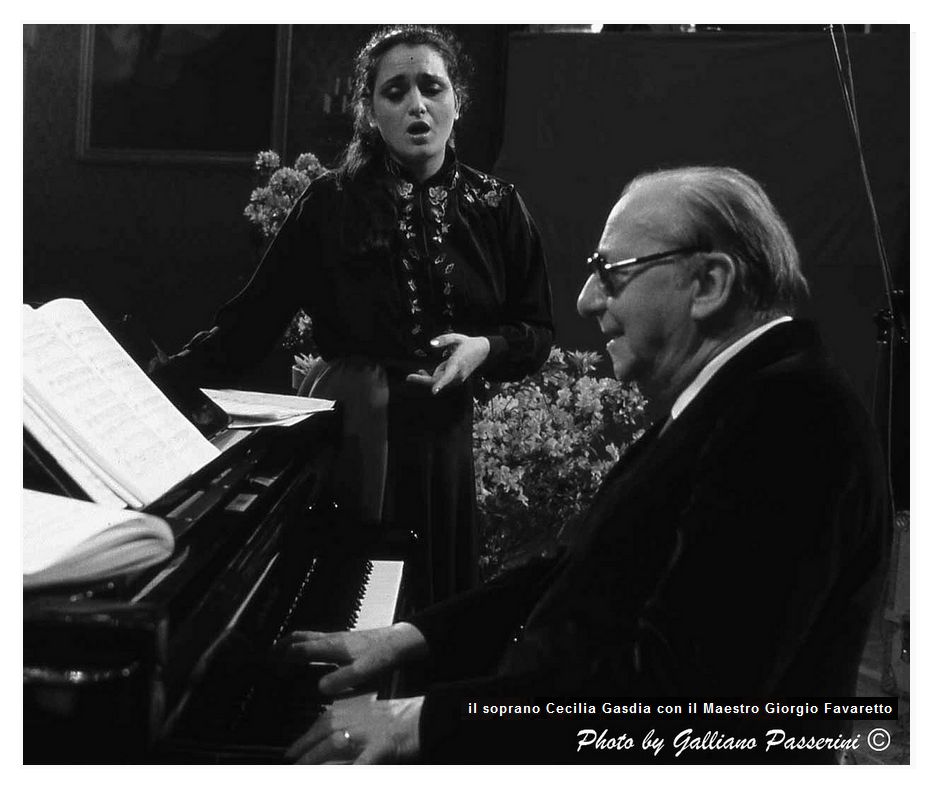

Buenos Aires, Rabat. Since the beginning of the career she has worked with Claudio

Scimone and I Solisti Veneti including an intense recording activity. -- Biography (slightly edited) from her official

website. Photo from the Bocelli website. |

BD: Were there contests, or just

auditions?

BD: Were there contests, or just

auditions?  CG: After trying for five years different roles and

different composers, I think I have finally understood what my way is

in opera, and what other things that I should do. It’s very difficult

to be able to know what to choose without trying it first, without singing

it first. I have come to the realization that it’s better for me

to sing Bellini, the dramatic Rossini, Donizetti and some Verdi at this

point. Sometime I will do Bohème, probably for the

reason that I am so young, but until I am thirty years old it is better

that I sing bel canto repertoire.

CG: After trying for five years different roles and

different composers, I think I have finally understood what my way is

in opera, and what other things that I should do. It’s very difficult

to be able to know what to choose without trying it first, without singing

it first. I have come to the realization that it’s better for me

to sing Bellini, the dramatic Rossini, Donizetti and some Verdi at this

point. Sometime I will do Bohème, probably for the

reason that I am so young, but until I am thirty years old it is better

that I sing bel canto repertoire.

Giuditta Angiola Maria Costanza Pasta (née Negri; 26 October 1797 – 1 April 1865), has been compared to the 20th-century soprano Maria Callas. She caused a sensation in Paris in 1821–22, in the role of Desdemona in Rossini's opera Otello. In Milan she created three roles which were written for her voice. They were the title role of Donizetti's Anna Bolena given at the Teatro Carcano in 1830 (and which was that composer's greatest success to date), Amina in Bellini's La sonnambula and the title role of his Norma (both in 1831), which became three of her major successes. Stendhal had argued persuasively in 1824 for the necessity of a score composed expressly for Pasta. Stendhal said her voice, “Can achieve perfect resonance on a note as low as bottom A, and can rise as high as C#, or even to a slightly sharpened D; and she possesses the rare ability to be able to sing contralto as easily as she can sing soprano. I would suggest ... that the true designation of her voice is mezzo-soprano, and any composer who writes for her should use the mezzo-soprano range for the thematic material of his music, while still exploiting, as it were incidentally and from time to time, notes which lie within the more peripheral areas of this remarkably rich voice. Many notes of this last category are not only extremely fine in themselves, but have the ability to produce a kind of resonant and magnetic vibration, which, through some still unexplained combination of physical phenomena, exercises an instantaneous and hypnotic effect upon the soul of the spectator. This leads to the consideration of one of the most uncommon features of Madame Pasta's voice: it is not all moulded from the same metallo, as it is said in Italy (which is to say that it possesses more than one timbre); and this fundamental variety of tone produced by a single voice affords one of the richest veins of musical expression which the artistry of a great cantatrice is able to exploit.”

Isabella Angela Colbran (2 February 1785 – 7 October 1845) was a Spanish opera singer known in her native country as Isabel Colbrandt. Many sources note her as a dramatic coloratura soprano, but some believe that she was a mezzo-soprano with a high extension, a soprano sfogato. She collaborated with opera composer Gioachino Rossini, whom she married in 1822, in the creation of a number of roles that remain in the repertory to this day. She was also the composer of four collections of songs. Descriptions of Colbran’s voice characterize the timbre as ‘sweet, mellow, with a rich middle register’. Rossini's music for her suggests perfect mastery of trills, half-trills, staccato, legato, ascending and descending scales, and octave leaps. Her vocal range extended from F-sharp below the staff to E above, with a high F sometimes available. All his life Rossini credited Colbran as being the greatest interpreter of his music. [Though not mentioned by Gasdia in the interview, two other singers should be included in this discussion. One is Giulia Grisi (1811-1860), whose second husband was the tenor known as Mario. She created Adalgisa in Norma and Elvira in I Puritani, and Donizetti wrote the roles of Norina and Ernesto in Don Pasquale for them. The other is Maria Malibran (1808-1836), whose father was Manuel Garcia. She created the title role in Maria Stuarda. Her immense vocal range was from D below middle C to F above high C.] |

CG: Almost all of them.

There are fewer written than what is normally sung. In fact, it’s

not exactly right that very light sopranos sing Bellini’s roles, as is

done today, because most of Bellini’s arias require a heavier and very

warm voice because they don’t go so high.

CG: Almost all of them.

There are fewer written than what is normally sung. In fact, it’s

not exactly right that very light sopranos sing Bellini’s roles, as is

done today, because most of Bellini’s arias require a heavier and very

warm voice because they don’t go so high.  BD: This production is your American debut?

BD: This production is your American debut?  CG: I sang Anne Truelove in The

Rake’s Progress.

CG: I sang Anne Truelove in The

Rake’s Progress.  BD: Do you do any modern operas

apart from the Stravinsky?

BD: Do you do any modern operas

apart from the Stravinsky?  BD: Is that also true with the other characters in that

opera?

BD: Is that also true with the other characters in that

opera?  BD: Have you made any records?

BD: Have you made any records? BD: Do you like playing a man?

BD: Do you like playing a man?

BD: That’s right, you end up alive!

BD: That’s right, you end up alive!

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on December 2, 1985. My thanks to Marina Vecci of Lyric Opera for providing the translations for us. Quotations were used on WNIB the following year, and again in 1995 and 2000. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.