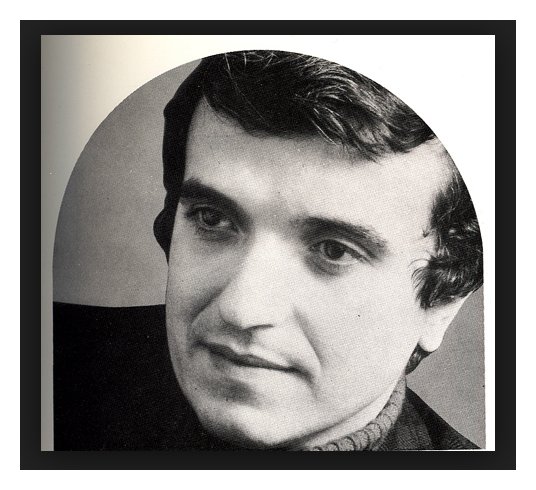

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

| Ruggero Raimondi was born in Bologna,

Italy, on October 3, 1941. His voice matured early into its adult timbre,

and at the age of 15, he auditioned for conductor Francesco Molinari-Pradelli,

who encouraged him to pursue an operatic career. He began vocal studies with

Ettore Campogalliani, and was accepted at age 16 as a student at the Giuseppe

Verdi Conservatory in Milan. He then continued his studies in Rome, under

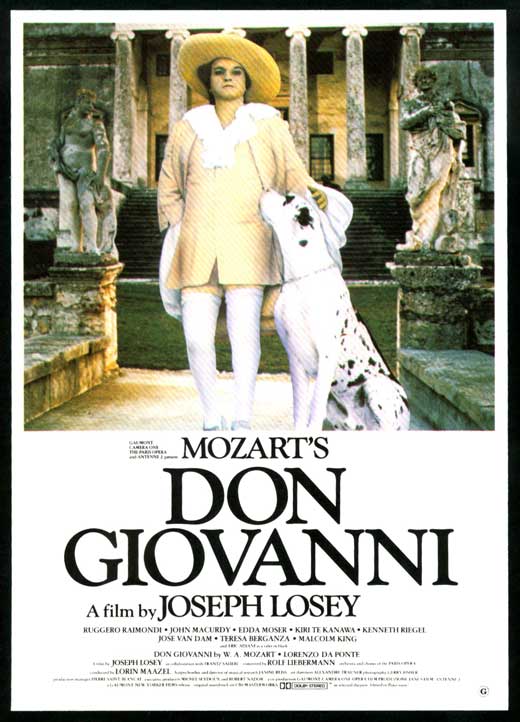

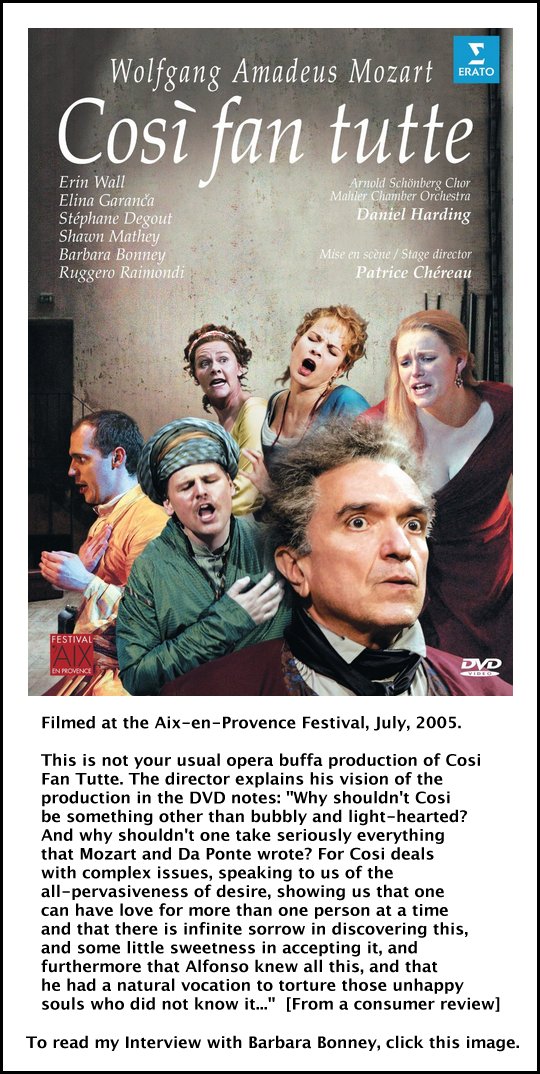

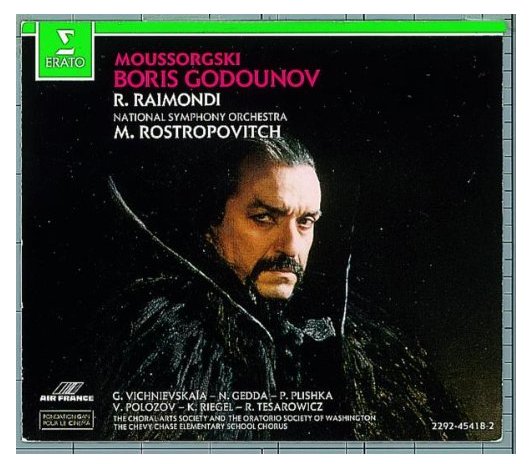

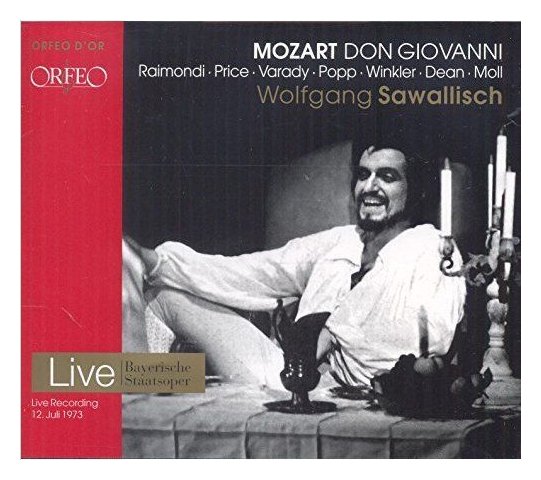

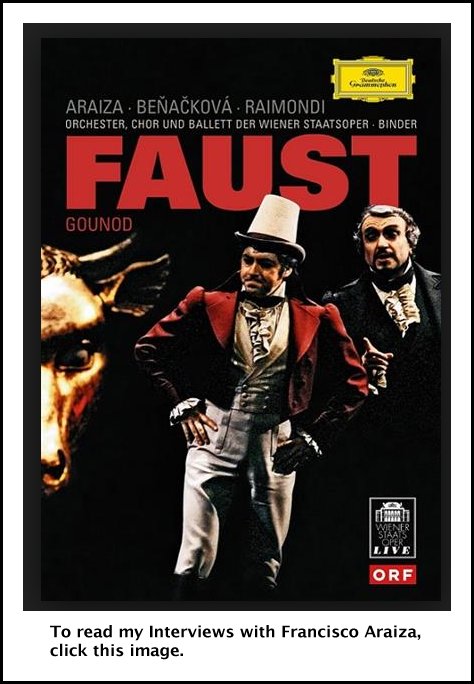

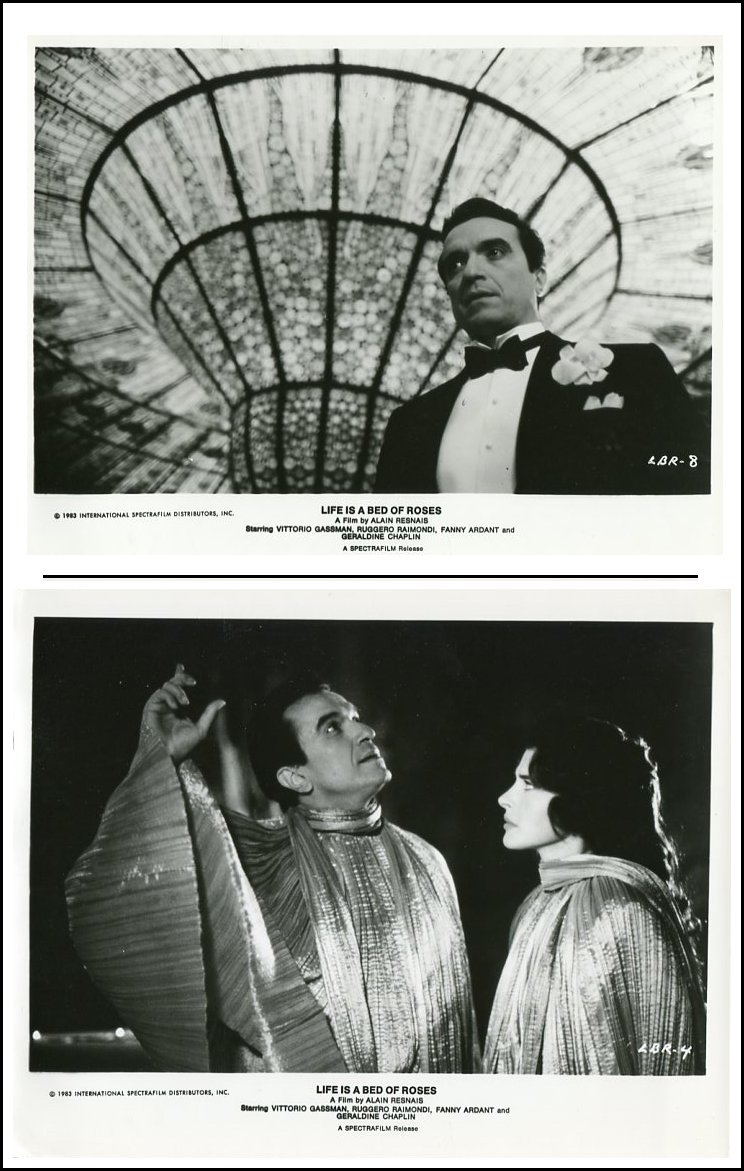

the guidance of Teresa Pediconi and Armando Piervenanzi. After having won the National Competition for young opera singers in Spoleto, he made his debut in the same city in the role of Colline in La Bohème in the Festival dei Due Mondi. Subsequently an opportunity arose for him at the Teatro dell'Opera in Rome when he was called upon to substitute in the role of Procida in Giuseppe Verdi's I Vespri Siciliani, and he received enormous success from the public and the critics. The young singer was very shy and stiff at first, but his early directors helped him, and he was soon an accomplished opera actor. Raimondi's career soon extended to the major opera houses in Italy, such as La Fenice in Venice, the Teatro Regio in Turin, Teatro Comunale in Florence and abroad, beginning with the Glyndebourne Festival (Don Giovanni in 1969). His La Scala debut was as Timur in Turandot in 1968, his Metropolitan Opera debut was as Silva in Ernani in 1970, and his Covent Garden debut was as Fiesco in Simon Boccanegra in 1972. In 1975, he made his Paris Opera debut as Procida, followed by the title role in Boris Godunov, and his Salzburg Festival debut in 1980 as the King in Aida. In 1986, he first directed a production of Don Giovanni, and decided to continue his career as a director as well. Some of his most important roles have been King Philip in Verdi's Don Carlos; Fiesco; the title roles in Boris Godunov (including the Andrzej Żuławski film) and Attila; Silva; Escamillo in Bizet's Carmen (including the Francesco Rosi film, 1984, with Plácido Domingo and Julia Migenes); the title role in Don Giovanni (including the Joseph Losey film, 1979); Count Almaviva in The Marriage of Figaro; and Don Alfonso in Così fan tutte; the title role in Don Quichotte by Massenet; and Scarpia in a recording of Tosca produced by Ardermann and later filmed live from Rome, with Plácido Domingo and Catherine Malfitano, conducted by Zubin Mehta. He also made the television film Six Characters in Search of a Singer. In 2008 he appeared in the Mini-Series Les Sanglot des Anges on French TV, in which he played the role of an Italian opera singer. In July 2011 he played the role of Pagano in Verdi's I Lombardi alla prima crociata on the rooftop of the Duomo of Milan. The concert was organized to celebrete the 150th Anniversary of the Italian Unity by the Veneranda Fabbrica del Duomo di Milano . -- Throughout this page, nmes

which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD

|

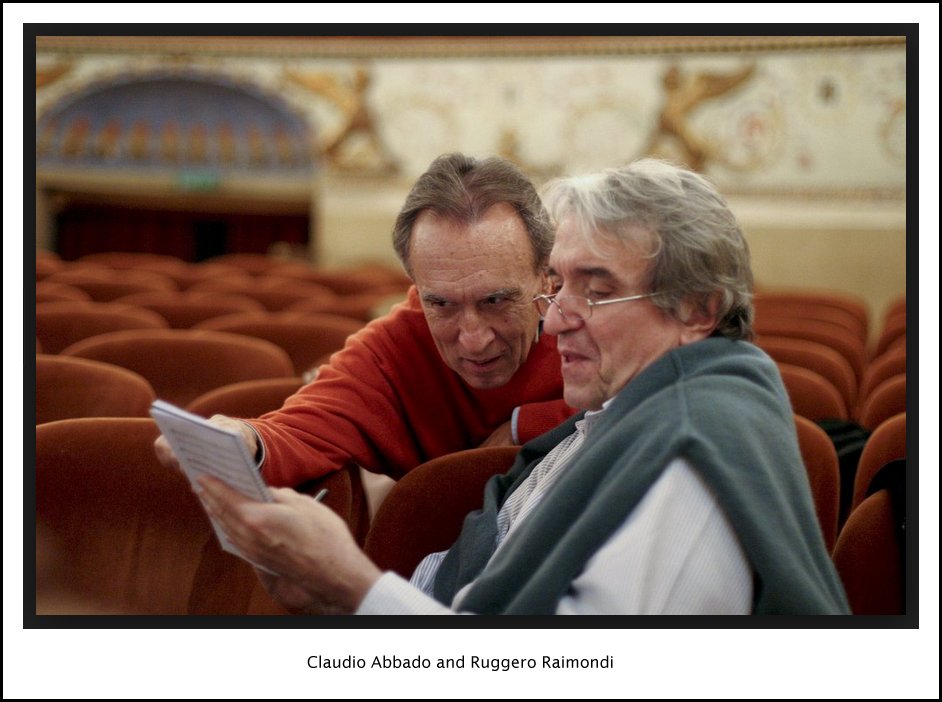

Raimondi then sang with Lyric Opera of Chicago in the 1987-88 season

in the sparkling new production of Marriage

of Figaro along with Felicity Lott (Countess),

Samuel Ramey (Figaro), Maria Ewing (Susanna), Frederica von Stade (Cherubino),

Arthur Korn (Bartolo) and Ugo Benelli (Basilio). Sir Andrew Davis conducted

and Sir Peter Hall directed.

Raimondi would only return once more to Lyric for Scarpia in Tosca in 2000-01, along with Daniela Dessì

(Tosca), Marcello Giordani (Cavaradossi) and David Cangelosi (Spoletta),

conducted by Bruno Bartoletti and staged by John Copley.

Raimondi then sang with Lyric Opera of Chicago in the 1987-88 season

in the sparkling new production of Marriage

of Figaro along with Felicity Lott (Countess),

Samuel Ramey (Figaro), Maria Ewing (Susanna), Frederica von Stade (Cherubino),

Arthur Korn (Bartolo) and Ugo Benelli (Basilio). Sir Andrew Davis conducted

and Sir Peter Hall directed.

Raimondi would only return once more to Lyric for Scarpia in Tosca in 2000-01, along with Daniela Dessì

(Tosca), Marcello Giordani (Cavaradossi) and David Cangelosi (Spoletta),

conducted by Bruno Bartoletti and staged by John Copley.

RR: I think he’s willing to live the life.

He’s very polygamous, very different. It depends on the conjecture of

the producer, the way the producer wants to make Don Giovanni. He can

take us straight away and go up on this, but we can make a Don Giovanni who

believes in himself. It is possible to have a Don Giovanni who doesn’t

believe in himself, or a Don Giovanni who is completely metaphysical, who

believes in God but is fighting the thinking of this Don Giovanni. You

can do a lot of things to Don Giovanni, but it is more important to put him

in the milieu where the personality

can grow up. Nowadays it would be quite difficult to believe in a

‘Don Giovanni’ because if you put him in

our century, what can he be? We think about him now as the anti-Christ.

Today it’s possible for him to be a Christian even though his morality is

open. You see there are more problems! Or you have to put him

inside some psychiatric search. That’s where it becomes difficult for

him to be intellectual, and I don’t think Don Giovanni is intellectual.

RR: I think he’s willing to live the life.

He’s very polygamous, very different. It depends on the conjecture of

the producer, the way the producer wants to make Don Giovanni. He can

take us straight away and go up on this, but we can make a Don Giovanni who

believes in himself. It is possible to have a Don Giovanni who doesn’t

believe in himself, or a Don Giovanni who is completely metaphysical, who

believes in God but is fighting the thinking of this Don Giovanni. You

can do a lot of things to Don Giovanni, but it is more important to put him

in the milieu where the personality

can grow up. Nowadays it would be quite difficult to believe in a

‘Don Giovanni’ because if you put him in

our century, what can he be? We think about him now as the anti-Christ.

Today it’s possible for him to be a Christian even though his morality is

open. You see there are more problems! Or you have to put him

inside some psychiatric search. That’s where it becomes difficult for

him to be intellectual, and I don’t think Don Giovanni is intellectual.| Andrea Palladio (30 November 1508

– 19 August 1580) was an Italian architect active in the Republic of Venice.

Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily by Vitruvius,

is widely considered to be the most influential individual in the history

of architecture. All of his buildings are located in what was the Venetian

Republic, but his teachings, summarized in the architectural treatise, The Four Books of Architecture, gained

him wide recognition. The city of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the

Veneto are UNESCO World Heritage Sites. |

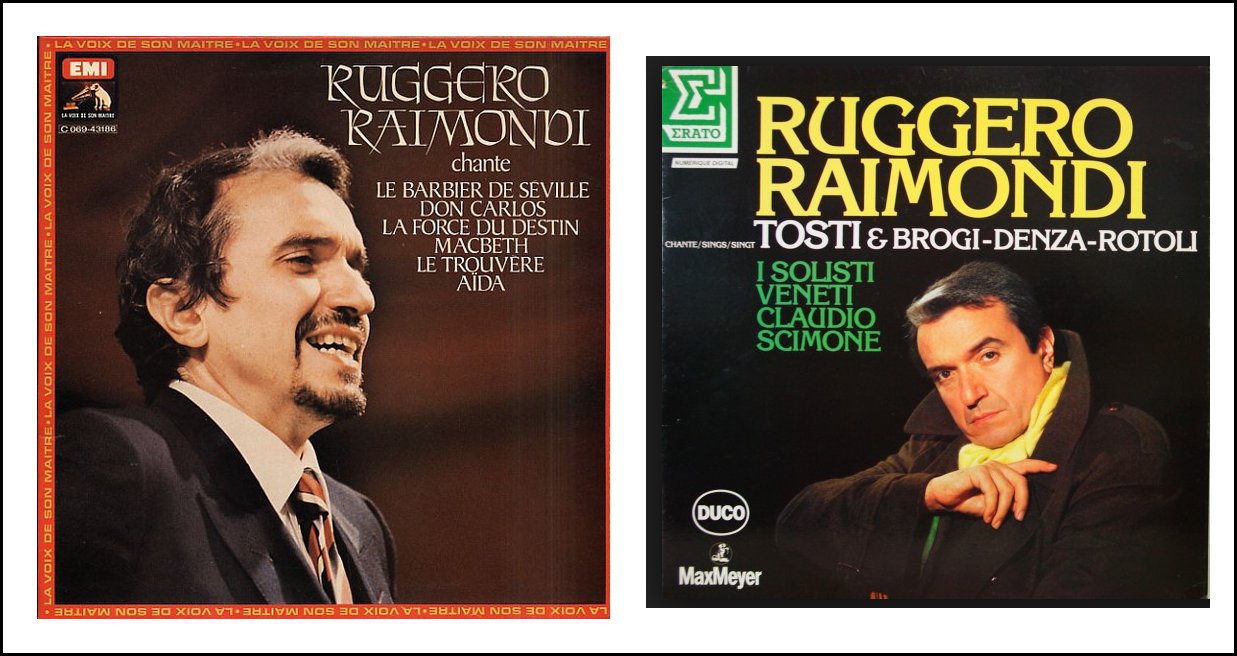

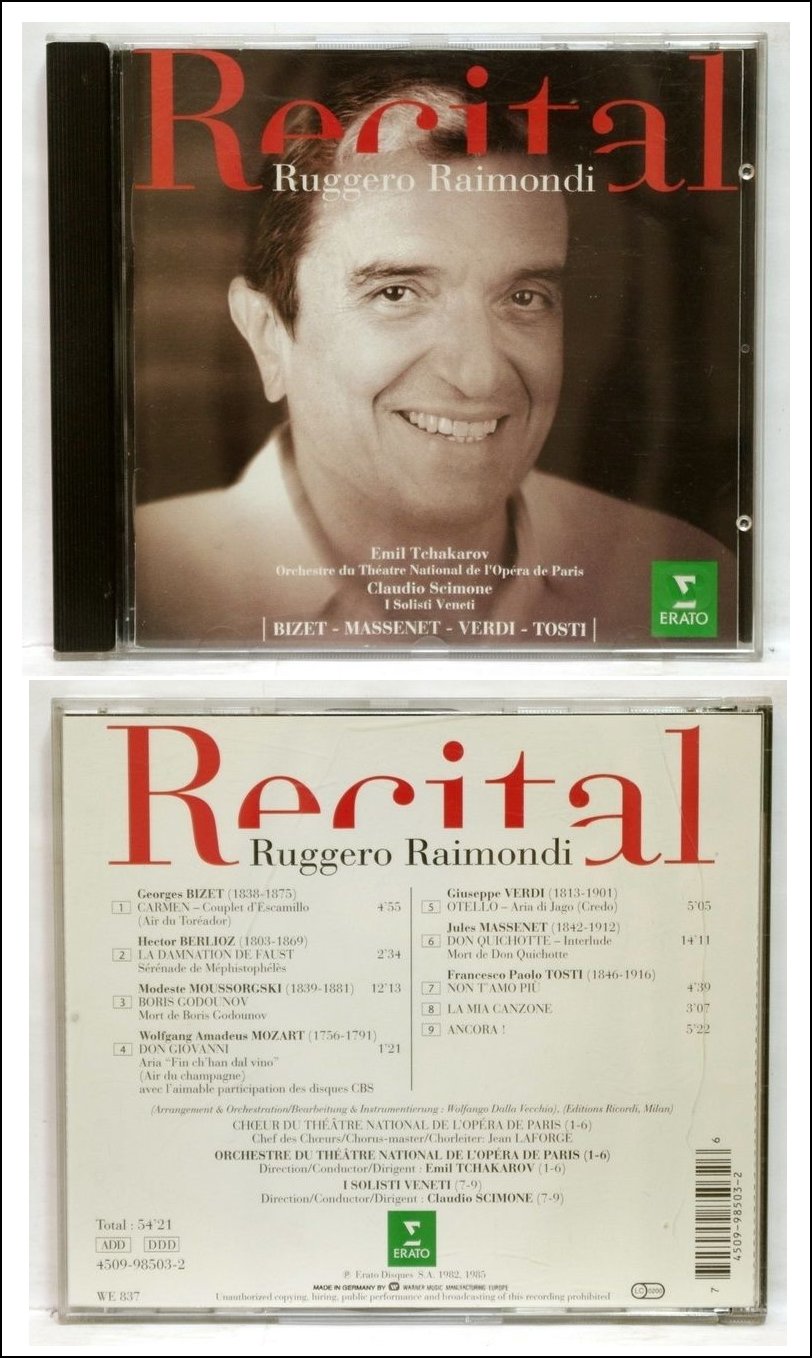

BD: But you’ve made a number of studio records.

Are you not pleased with them?

BD: But you’ve made a number of studio records.

Are you not pleased with them? BD: [With a gentle nudge] No???

BD: [With a gentle nudge] No??? RR: Oh, a lot! This is a new way to see the

opera, and they do it in such a way because they don’t have ideas.

It’s very difficult to remain inside of a style and a century when the opera

was brought about. I always try to avoid productions where they are

afraid to be original.

RR: Oh, a lot! This is a new way to see the

opera, and they do it in such a way because they don’t have ideas.

It’s very difficult to remain inside of a style and a century when the opera

was brought about. I always try to avoid productions where they are

afraid to be original. | The Paradox of Acting was written by Denis

Diderot between 1773 and 1777 and was published posthumously in 1830. In

the book, Diderot opposes the conventional wisdom of actors at the time who

assumed that to be convincing, the actor must feel the passion being expressed.

This of course is what Stanislavski went on to formulate in 'The System'.

Diderot argues that these manifestations of emotions are not great acting

and that the actor must show self-control to explore first these passions,

and then reproduce them. The argument became between what were called the

'emotionalist' and 'anti-emotionalist' supporters. Crucially the distinction between the emotionalists 'experiencing the role' and non-emotionalists 'representing the role' rests on their relationship with that role during performance. For Stanislavski and the emotionalists, the actor should become the character , no longer experiencing a distinction between his or her self and that character; the actor has created a 'third being', a combination of the actor's personality and the role, a ''re-incarnation' or 'metamorphosis'. However Stanislavski goes to some lengths to insist that both styles (though only these two) deserve to be regarded as 'art'. He called his own approach 'experiencing the role' and the other the 'art of representation.' Stanislavski identifies this style with the French actor Coquelin, who writes in support of Diderot, "The truth according to my mind is that in order to call forth emotion we ourselves must not feel it; and that the actor must in all circumstances remain the absolute master of himself, and leave nothing to chance." (The Art of the Actor 1894) Diderot was far from the first to write about acting. From the earliest Greek theater there has been recognition that on the one hand there is the need for the actor to be affected by the sensations he wishes to arouse in others, and on the other a need for a precise system of expression - the right look, tone, and gesture appropriate to every emotion of the mind. Consider what Aristotle has to say, "We mold ourselves with facility to the imitation of every form; by the other, transported out of ourselves, we become what we imagine." In Commedia dell 'arte, each character became an extension of the actor's own personality, but elastic enough to respond to innumerable dramatic situations. The notion of improvisation and "being the character" were born. What Diderot calls 'the actor's paradox' is clear in 'the art of representation' approach. While on-stage the actors experience the distinction between themselves and the roles they are playing. Coquelin refers to it and 'dualism', "One part of him is the performer, the instrumentalist; another, the instrument to be played on." |

RR: Oooo! Who knows? For example, in

Boris, when he dies is truly a

moment of pain. Sometimes I feel I am a masochist because I’m doing

to myself such pain that I have a heart attack. That might be one of

the right solutions. But it’s difficult to drive yourself in such a

masterpiece because you become involved also with feelings you don’t want.

RR: Oooo! Who knows? For example, in

Boris, when he dies is truly a

moment of pain. Sometimes I feel I am a masochist because I’m doing

to myself such pain that I have a heart attack. That might be one of

the right solutions. But it’s difficult to drive yourself in such a

masterpiece because you become involved also with feelings you don’t want. BD: No, I’m trying to find out how you see

him because he’s so complex.

BD: No, I’m trying to find out how you see

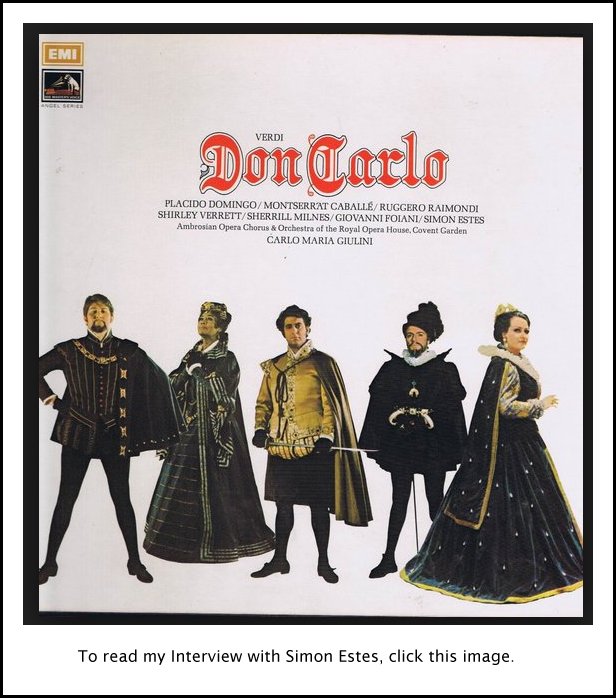

him because he’s so complex. RR: Filippo II is a fantastic personality out

of historical context. It’s from Friedrich Schiller. The duet

with Posa, who is supposed to be the man who believes in human rights and

believes in sincerity, is one of the masterpieces of the theater. This

duet with Posa is one of the high moments for me.

RR: Filippo II is a fantastic personality out

of historical context. It’s from Friedrich Schiller. The duet

with Posa, who is supposed to be the man who believes in human rights and

believes in sincerity, is one of the masterpieces of the theater. This

duet with Posa is one of the high moments for me.| Louis Massignon (25 July 1883 –

31 October 1962) was a Catholic scholar of Islam and a pioneer of Catholic-

Muslim mutual understanding. He was an influential figure in the twentieth

century with regard to the Catholic church's relationship with Islam. He focused

increasingly on the work of Mahatma Gandhi, whom he considered a saint. He

was also influential, among Catholics, for Islam being accepted as an Abrahamic

Faith. Some scholars maintain that his research, esteem for Islam and Muslims,

and cultivation of key students in Islamic studies largely prepared the way

for the positive vision of Islam articulated in the Lumen gentium and the Nostra aetate at the Second Vatican Council.

Although a Catholic himself, he tried to understand Islam from within and

thus had a great influence on the way Islam was seen in the West; among other

things, he paved the way for a greater openness inside the Catholic Church

towards Islam. |

RR: I prefer being an artist, but it’s difficult

nowadays to be one.

RR: I prefer being an artist, but it’s difficult

nowadays to be one.

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in a backstage dressing room of the Civic Opera House in Chicago on November 16, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB about a month later, and again the following year and in 1996. This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.