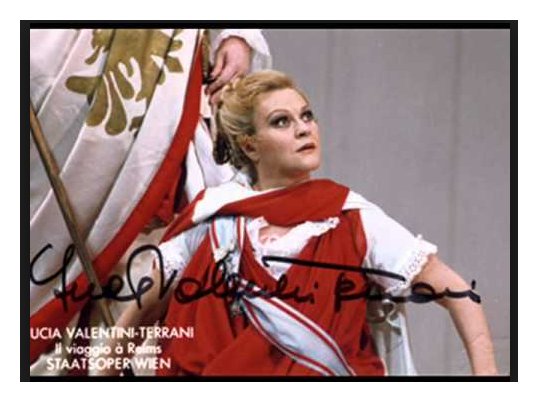

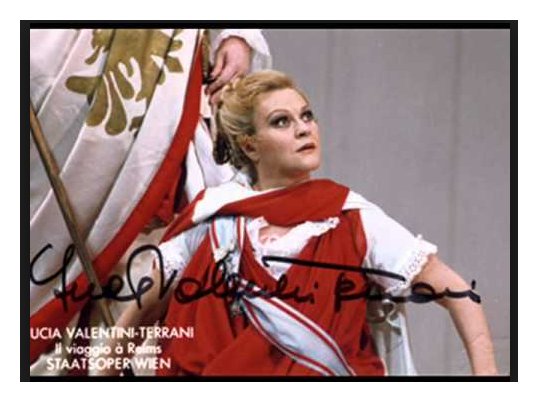

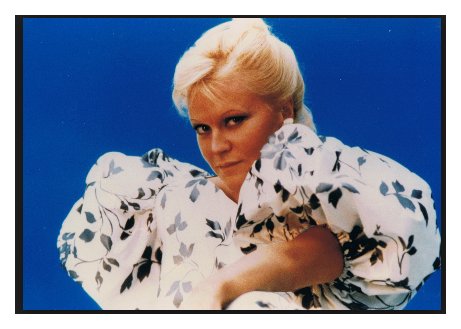

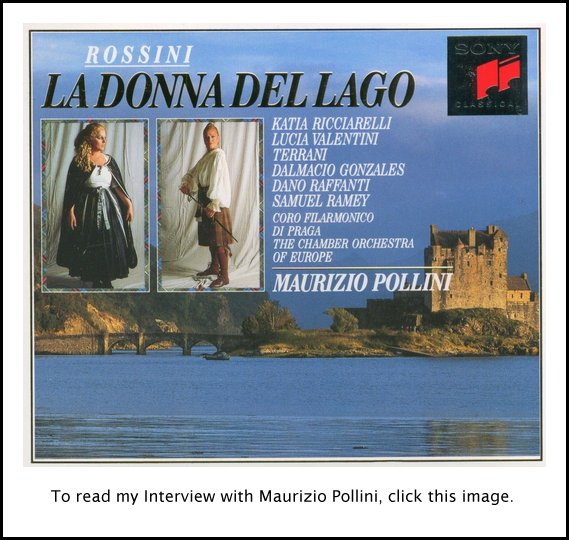

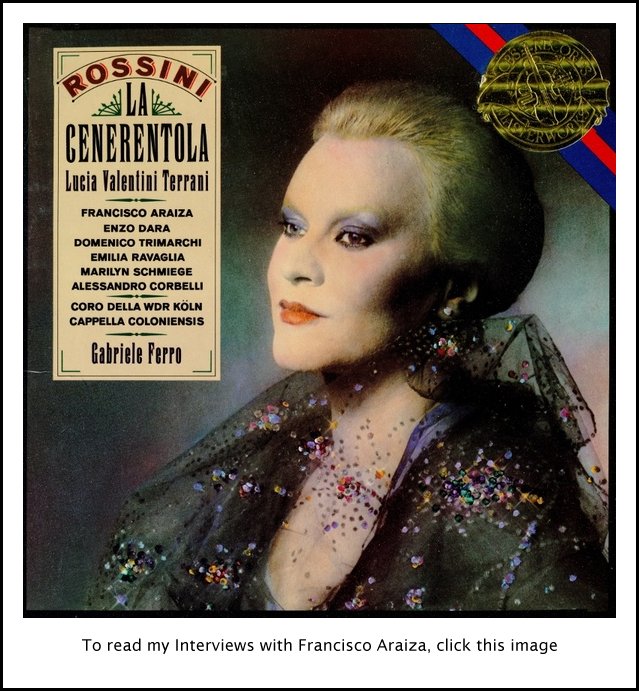

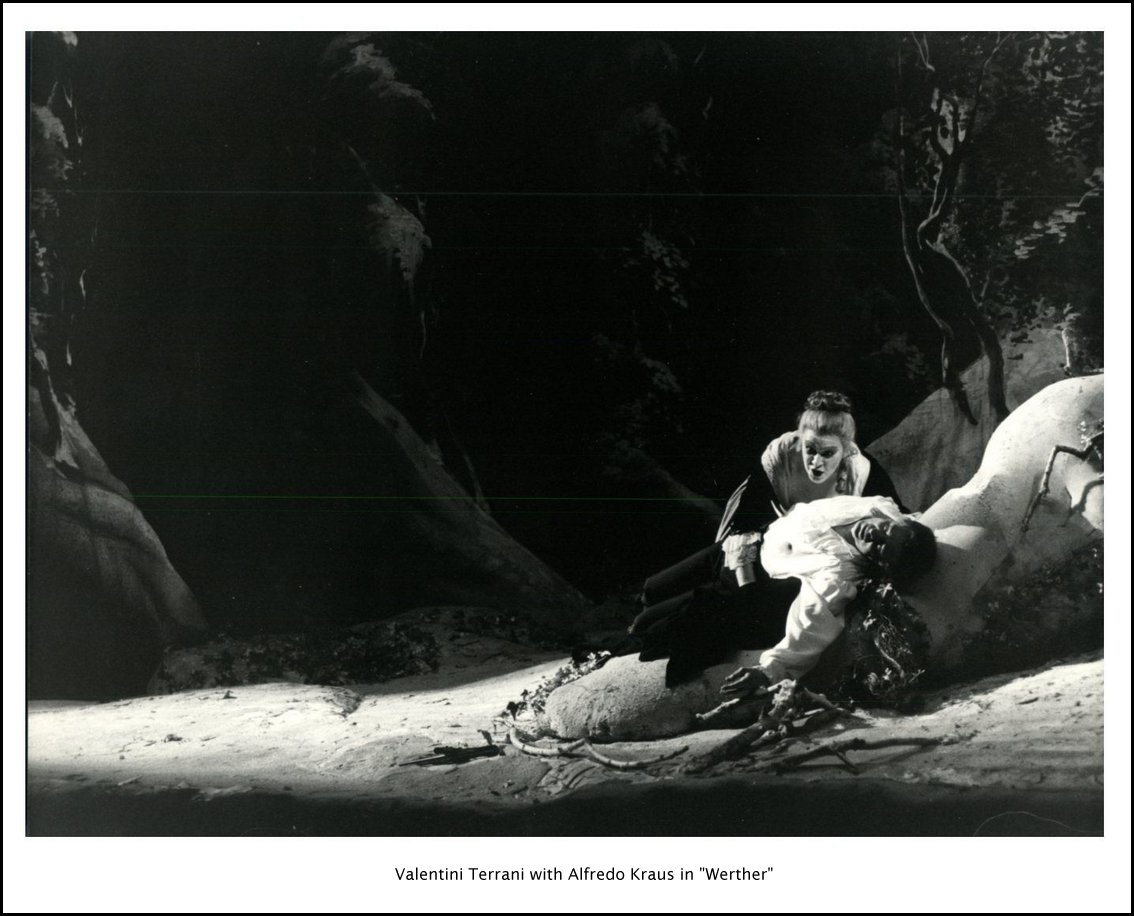

| Born: August 28, 1946, Padua, Italy Died: June 11, 1998, Seattle, Washington, USA The Italian coloratura mezzo-soprano, Lucia Valentini Terrani (born: Lucia Valentini), studied first at the Padua Music Conservatory, and later at the Accademia Benedetto Marcello in Venice. She made her stage debut in Brescia, as Angelina in La cenerentola, a role she will remain closely associated with throughout her career. She made her debut at La Scala in 1973, again as Angelina, and quickly established herself in the Rossini repertoire, singing in L'italiana in Algeri, Il barbiere di Siviglia, Il viaggio a Reims. She also sang the many "trouser roles" such as Tancredi, Malcolm in La donna del lago, Pippo in La gazza ladra, Calbo in Maometto secondo, Arsace in Semiramide, Isolier in Le comte Ory, etc. She also sang a few roles of the Baroque repertory, notaby Monteverdi 's L'Orfeo, and Bradamante in George Frideric Handel 's Alcina. However, she did not restrict herself to the belcanto and expanded her repertoire to include roles such as Dorabella, Eboli, Quickly, Mignon, Octavian, Charlotte, Dulcinée. Valentini Terrani enjoyed a very successful international career, appearing in Paris, London, Moscow, Buenos Aires, Chicago, Los Angeles, Washington, etc. Lucia Valentini married Italian actor Alberto Terrani in 1973, and added his surname to hers. She was diagnosed with leukemia in 1996, and went to the famous Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle for treatment, where her colleague and friend José Carreras was treated for the same affliction. Sadly she was not as lucky as Carreras, and died of complications following a bone marrow transplant at the age of 51. |

|

Lucia Valentini Terrani in Chicago

Lyric Opera 1976 - Cenerentola (Title Role) with Alva, Romero,

Montarsolo,

Nolen, Azarmi, Hines; Rescigno, Ponnelle

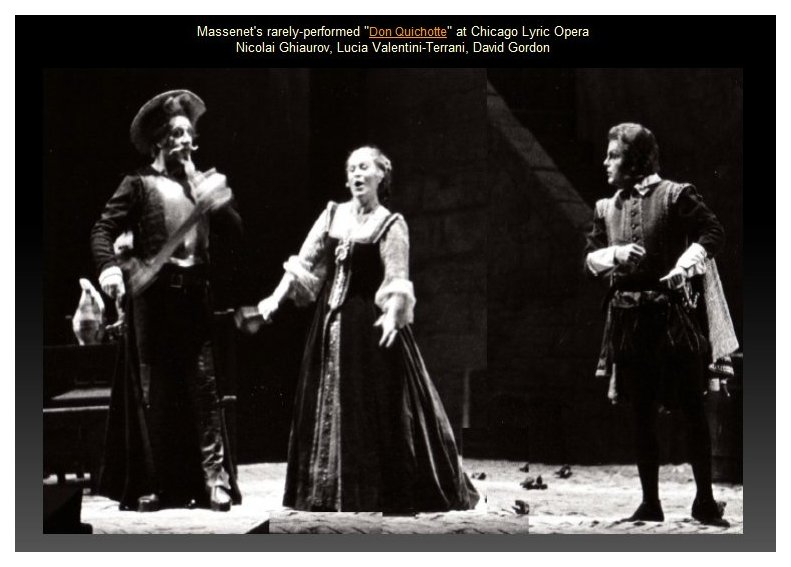

1981 - Don Quichotte (Dulcinée) with Ghiaurov, Gramm, Gordon, Negrini, Cook; Fournet, Samaritani, Tallchief [Photo from this production is shown farther down on this webpage.] Chicago Symphony Orchestra and

Chorus

(All performances conducted by Claudio Abbado, with Chorus Master Margaret Hillis) February, 1977 - Alexander Nevsky

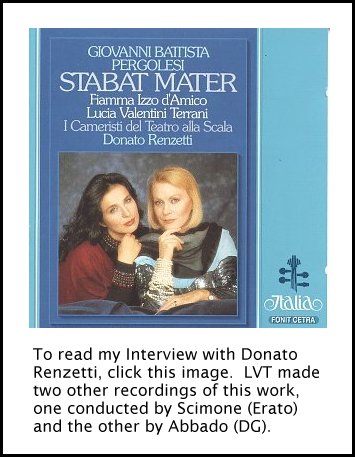

March, 1981 - Joshua [Mussorgsky] with Philip Kraus and Oedipus Rex (Jocasta) with Schell, Langridge, Shirley-Quirk, Haugland, Blake, Gramm February, 1984 - Stabat Mater [Pergolesi] with Beňačková November, 1984 - Boris Godunov (Marina) with Raimondi, Kaludov, Ramey, Shirley-Quirk, Langridge, Kaasch -- Throughout this webpage, names which are links

refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD

|

Naturally, we spoke of Massenet, and that section of her remarks was

published in the Massenet Newsletter

soon thereafter. Other portions were aired on WNIB, Classical 97, when

we played some of her recordings, and now I am pleased to present the entire

conversation on this webpage.

Naturally, we spoke of Massenet, and that section of her remarks was

published in the Massenet Newsletter

soon thereafter. Other portions were aired on WNIB, Classical 97, when

we played some of her recordings, and now I am pleased to present the entire

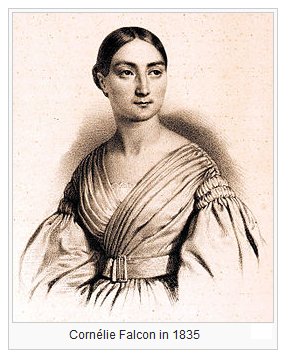

conversation on this webpage.Cornélie Falcon (28 January

1814 – 25 February 1897) was a French soprano who sang at the Opéra

in Paris. Her greatest success was creating the role of Valentine in Meyerbeer's

Les Huguenots. She possessed

"a full, resonant voice" with a distinctive dark timbre and was an exceptional

actress. Based on the roles written for her voice her vocal range spanned

from low A-flat to high D, 2.5 octaves. She and the tenor Adolphe Nourrit

are credited with being primarily responsible for raising artistic standards

at the Opéra, and the roles in which she excelled came to be known

as "falcon soprano" parts. She had an exceptionally short career, essentially

ending about five years after her debut, when at the age of 23 she lost her

voice during a performance of Niedermeyer's Stradella. Cornélie was enrolled at the Paris Conservatory from 1827 to 1831.

There she first studied with Felice Pellegrini and François-Louis

Henry, and later with Marco Bordogni and Adolphe Nourrit. She won a second

prize in solfège in 1829, a first prize in vocalization in 1830, and

a first prize in singing in 1831.

Cornélie was enrolled at the Paris Conservatory from 1827 to 1831.

There she first studied with Felice Pellegrini and François-Louis

Henry, and later with Marco Bordogni and Adolphe Nourrit. She won a second

prize in solfège in 1829, a first prize in vocalization in 1830, and

a first prize in singing in 1831.At the invitation of Nourrit she made her debut at the age of 18 at the Opéra as Alice in the 41st performance of Meyerbeer's Robert le diable (20 July 1832). The cast included Nourrit and Julie Dorus (who had premiered the role in 1830). The director of the Opéra, Louis Véron, had made certain there was plenty of advance publicity, and the auditorium was packed. The audience included the composers Rossini, Berlioz, Cherubini, Halévy, and Auber, the singers Maria Malibran, Caroline Branchu, and Giulia Grisi, and two of France's greatest actresses from the Comédie-Française, Mademoiselle Mars and Mademoiselle Georges. Other audience members included the painters Honoré Daumier and Ary Scheffer, the librettist Eugène Scribe, and the critics and writers Théophile Gautier, Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, and Alfred de Musset. Although understandably suffering from stage fright, Falcon managed to sing her first aria without error, and finished her role with "ease and competence." Her tragic demeanor and dark looks were highly appropriate to the part, and she made a vivid impression on the public. Berlioz's admiration for the singer was considerable, and with Véron's permission he engaged her for one of his concerts which he organized that winter in the hall of the Paris Conservatory. It was the second in the series and was presented on 23 November 1834 with Narcisse Girard conducting. Falcon sang Berlioz's new orchestrations of the songs La captive and Le Jeune Pâtrie breton, and earned an encore in which she sang an aria by Bellini. The concert also featured the premiere of Berlioz's new symphony Harold en Italie, and the audience included the Duc d'Orléans, Chopin, Liszt, and Victor Hugo. With the new symphony and Falcon as the star singer, the receipts were more than double those of the first concert on 9 November, which had featured the Symphonie fantastique and the overture Le Roi Lear. However, La captive, and not Harold, was the hit of the show, with the Gazette Musicale (7 December 1834) calling it "a masterpiece of melodic skill and orchestration." Falcon's other creations at the Opéra included the roles of Rachel in Halévy's La Juive (23 February 1835), Valentine in Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots (29 February 1836), the title role in Louise Bertin's La Esmeralda (14 November 1836), and Léonor in Louis Niedermeyer's Stradella (3 March 1837). She also appeared as the Countess in Rossini's Le comte Ory and Pamira in Rossini's Le siège de Corinthe (1836). Many explanations have been offered for Falcon's loss of voice, including the enormous demands of the music of Grand Opera, the "ill-effects of beginning to sing in a large opera house before her body was fully mature", Falcon's attempts to lift her range above its natural mezzo-soprano range, and nervous fatigue brought on by her personal life. Benjamin Walton has analyzed the music written for her and has suggested there was a break in her voice between a' and b♭'. Gilbert Duprez, who sang with her on several occasions, speculated that her inability to negotiate this transition was a factor in her "vocal demise". By 1835, Falcon was earning 50,000 francs/year at the Opéra, making her the highest paid artist there, earning nearly twice as much as Nourrit and three times as much as Dorus. |

BD:

Is there a different kind of strength because you’re portraying a man as

Arsace?

BD:

Is there a different kind of strength because you’re portraying a man as

Arsace? LVT: My career was born with Cenerentola, and

it’s the most congenial, the closest to me. The reason is hard to define.

It’s just something like a love affair. There’s no logical explanation.

We can’t say why like one or the other. It’s just there.

LVT: My career was born with Cenerentola, and

it’s the most congenial, the closest to me. The reason is hard to define.

It’s just something like a love affair. There’s no logical explanation.

We can’t say why like one or the other. It’s just there.

| Although the original version of

Tancredi, presented at the

Teatro La Fenice in Venice on 6 February 1813, had a happy ending (as required

by the opera seria tradition), soon after the Venice premiere, Rossini —

who was more of a Neo-classicist than a Romantic, notes Servadio — had the

poet Luigi Lechi rework the libretto to emulate the original tragic ending

by Voltaire. In this new ending, presented at the Teatro Comunale in Ferrara

on 21 March 1813, Tancredi wins the battle but is mortally wounded, and only

then does he learn that Amenaide never betrayed him. Argirio marries the

lovers in time for Tancredi to die in his wife's arms. As has been stated by Philip Gossett and Patricia Brauner, it was the rediscovery of the score of this ending in 1974 (although elsewhere Gossett provides evidence that it was 1976) that resulted in the version which is usually performed today |

BD: Has she sung some unknown works such as

Salieri or Pergolesi?

BD: Has she sung some unknown works such as

Salieri or Pergolesi?© 1981 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at her apartment in Chicago on December 2, 1981. The translation was provided by Marina Vecci of Lyric Opera of Chicago. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1985, 1989 and 1996. The remarks about her Massenet roles were published in the Massenet Newsletter in January, 1986. This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.