|

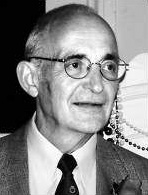

Bruce MacCombie (born December 5, 1943 in Providence, Rhode Island

died May 2, 2012 in Amherst, Massachusetts) was an American composer.

Bruce MacCombie (born December 5, 1943 in Providence, Rhode Island

died May 2, 2012 in Amherst, Massachusetts) was an American composer.

He studied at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Freiburg

Conservatory, and holds a Ph.D. in music from the University of Iowa. He

was appointed to the music faculty of Yale University in 1975, and one year

later joined the composition faculty of the Yale School of Music.

MacCombie was Director of Publications for G. Schirmer and Associated

Music Publishers from 1980 to 1986, Dean of the Juilliard School from 1986

to 1992 and Dean of the School for the Arts at Boston University from 1992

to 2001. Beginning in 2002 he was Professor of Music at the University of

Massachusetts Amherst at Amherst, and was Executive Director of Jazz at Lincoln

Center from 2001 to 2004.

His compositions include Nightshade Rounds (1979) for solo

guitar (written for Sharon Isbin), Leaden Echo, Golden Echo (1989)

for soprano and orchestra, the set of choral pieces Color and Time

(1990), Chelsea Tango (1991) for orchestra, and the quintet Greeting

(1993) (written for Krzysztof Penderecki's

60th birthday).

* * *

* *

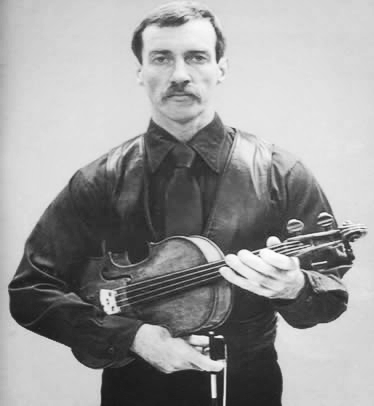

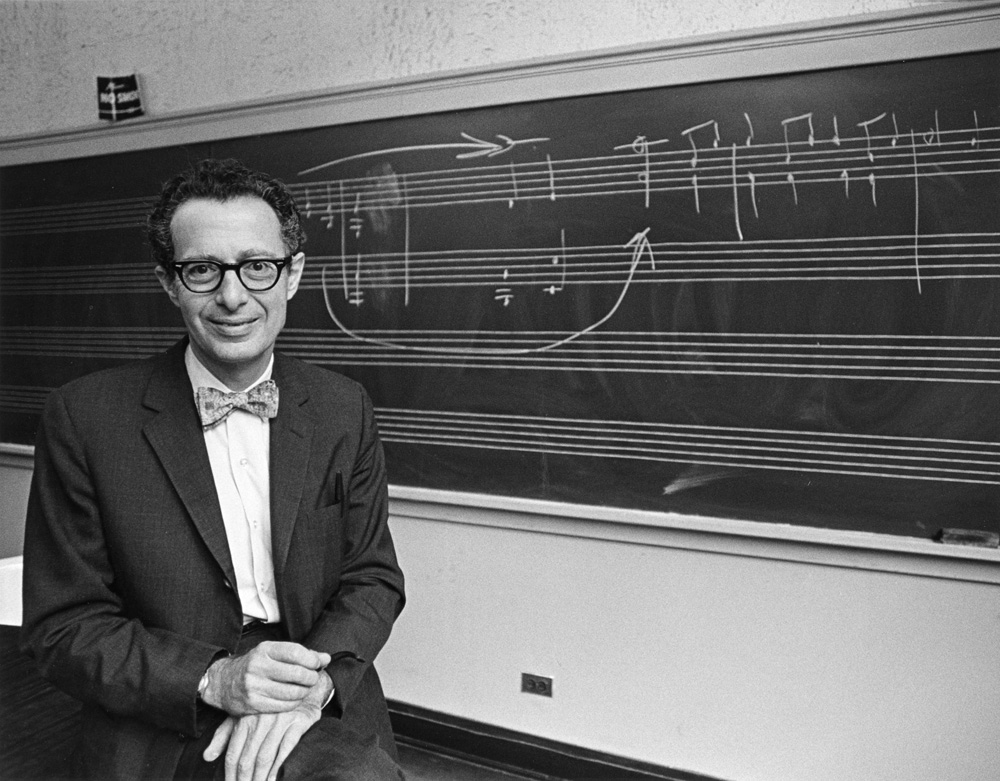

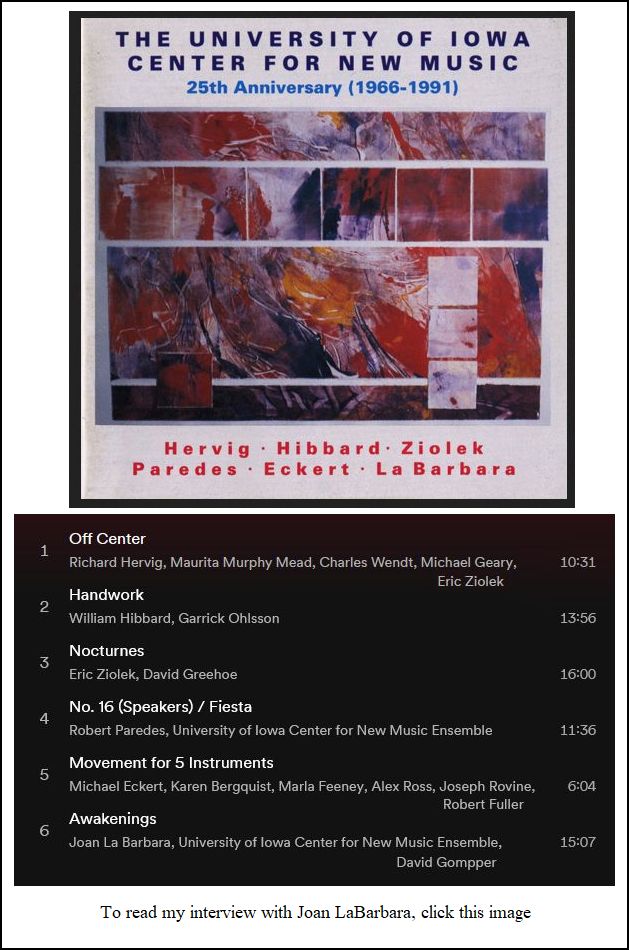

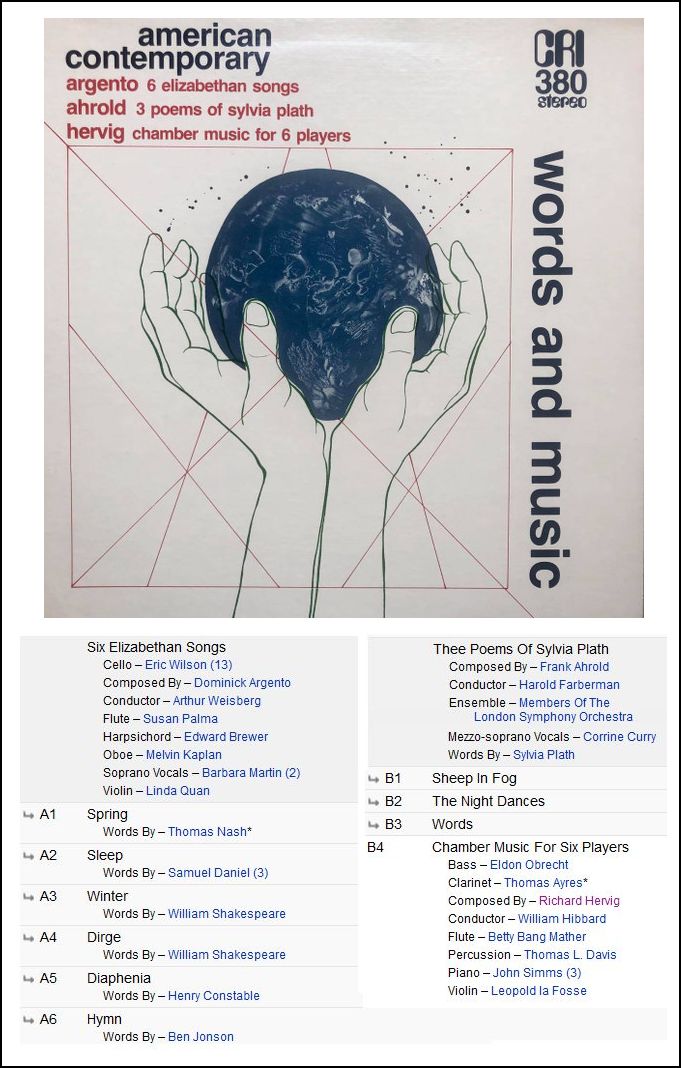

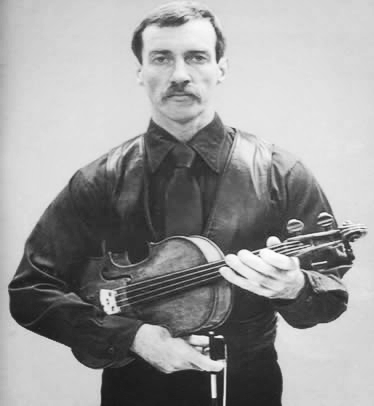

William Hibbard (August 8, 1939 - April 5, 1989)

William Hibbard (August 8, 1939 - April 5, 1989)

B.Mus. in Violin, New England Conservatory of Music (1961)

M.Mus. in Composition, New England Conservatory of Music (1963)

Ph.D in Composition, University of Iowa (1967)

Principal teachers: Francis Judd Cooke, Donald Martino and Richard

Hervig

William Hibbard was a distinguished composer, conductor, violist

and teacher. He was appointed to the University of Iowa Music Composition

faculty in 1966, and promoted to full professor in 1977. He became Chair

of the Theory and Composition area in the School of Music in 1982. He served

as Music Director of the University's professional new music ensemble, the

Center for New Music, from its inception in 1966 through 1988. In addition,

he served as Director of the University's Center for New Performing Arts,

an interdisciplinary arts project funded jointly by the Rockefeller Foundation

and the University of Iowa, from 1965 through 1975. Both organizations have

made enormous contributions to the promotion, understanding and advancement

of new music and art. In 1986 the Center for New Music received the Commendation

of Excellence Award from Broadcast Music Inc (BMI). In 1990 the American

Composers Alliance conferred its Laurel Leaf Award upon the Center for New

Music "in memoriam William Hibbard."

As a violist, he served as Principal Viola of the Quad City Symphony

(James Dixon, Music Director) from 1984 through late 1988. In addition,

he was founder and Director of the Iowa City String Orchestra from 1980

to 1986.

As a composer, he wrote more than forty works, including compositions

for mixed chamber ensembles, voice, orchestra and solo instruments. His

musical compositions employ strict serial techniques with virtuoso instrumental

writing, contrapuntal complexity and unique orchestration. His composition

Ménage (1974) for soprano, trumpet and violin was

selected by the U.S. jury as one of five American works to be submitted

for the 1977 ISCM Festival in Bonn, Germany. In 1988 he was honored with

the Distinguished Alumnus Award from the New England Conservatory.

Hibbard died of AIDS in San Francisco at the age of 49 on April

5, 1989.

When asked to describe his music for the Lingua Press Collection

II Catalogue, he wrote: "When asked for my views of my own music I freeze.

Such requests seek to elicit a verbal – and, it seems to me falsely concrete

– grasp to a composer's sonic abstractions. Personally, I desire to fashion

something wrought well. Logic and imagination interact to fertilize and

focus those desires so that, in the end, the music itself may say it all."

— Paul Paccione, on the American Composers Alliance

website

* * *

* *

Donald Martin Jenni (born Milwaukee, October 4, 1937 – died New Orleans

June 21, 2006) was an American composer, musicologist, and educator. A piano

and composition prodigy, Jenni began weekend studies with composer Leon Stein in 1950, and

published several compositions before graduating from high school in 1954;

he was "championed" during his teen years by composer Henry Cowell.

Donald Martin Jenni (born Milwaukee, October 4, 1937 – died New Orleans

June 21, 2006) was an American composer, musicologist, and educator. A piano

and composition prodigy, Jenni began weekend studies with composer Leon Stein in 1950, and

published several compositions before graduating from high school in 1954;

he was "championed" during his teen years by composer Henry Cowell.

In 1954, he began his undergraduate education at De Paul University

in Chicago, earning a bachelor's degree in music; he was also choirmaster

at St. Patrick's Church in South Chicago, Chicago from 1955-60. He earned

a master's degree in Medieval Studies from the University of Chicago in 1962

and a doctorate in music composition from Stanford University in 1966.

He taught at De Paul University Chicago from 1962–68, then

joined the faculty in music composition and theory at the University of Iowa

from 1968. He was tenured in 1974, and served as head of Iowa's composition

and theory areas from 1990-1997.

|

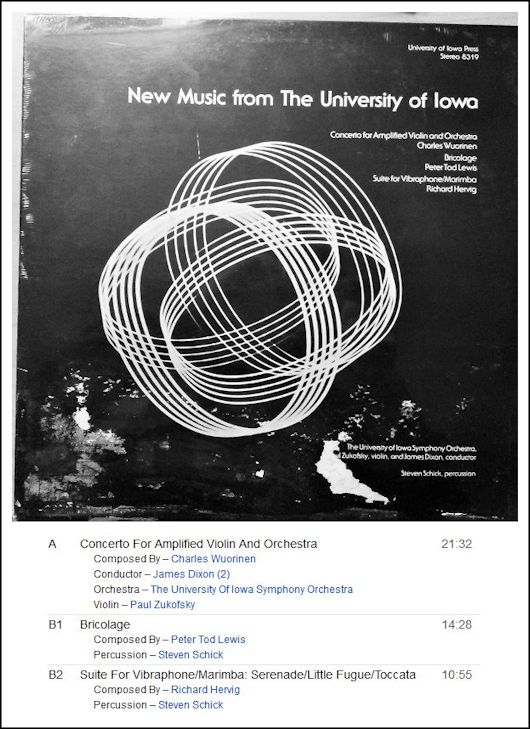

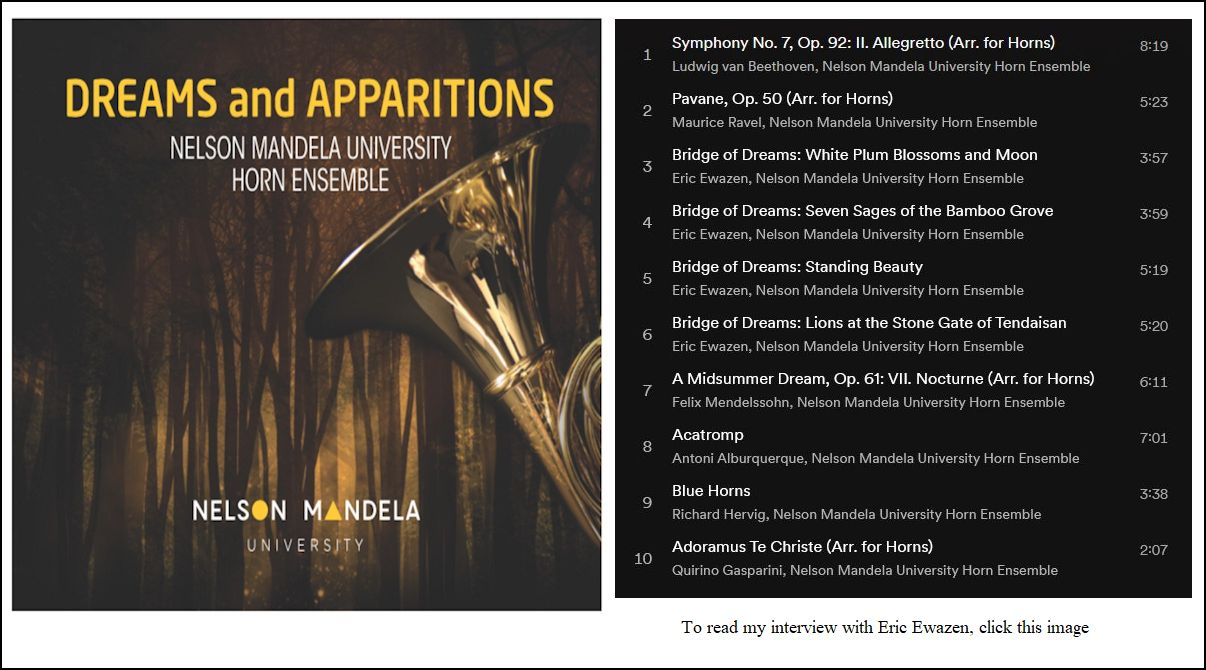

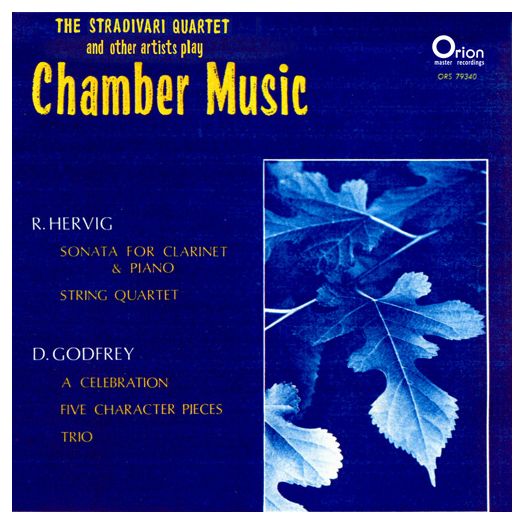

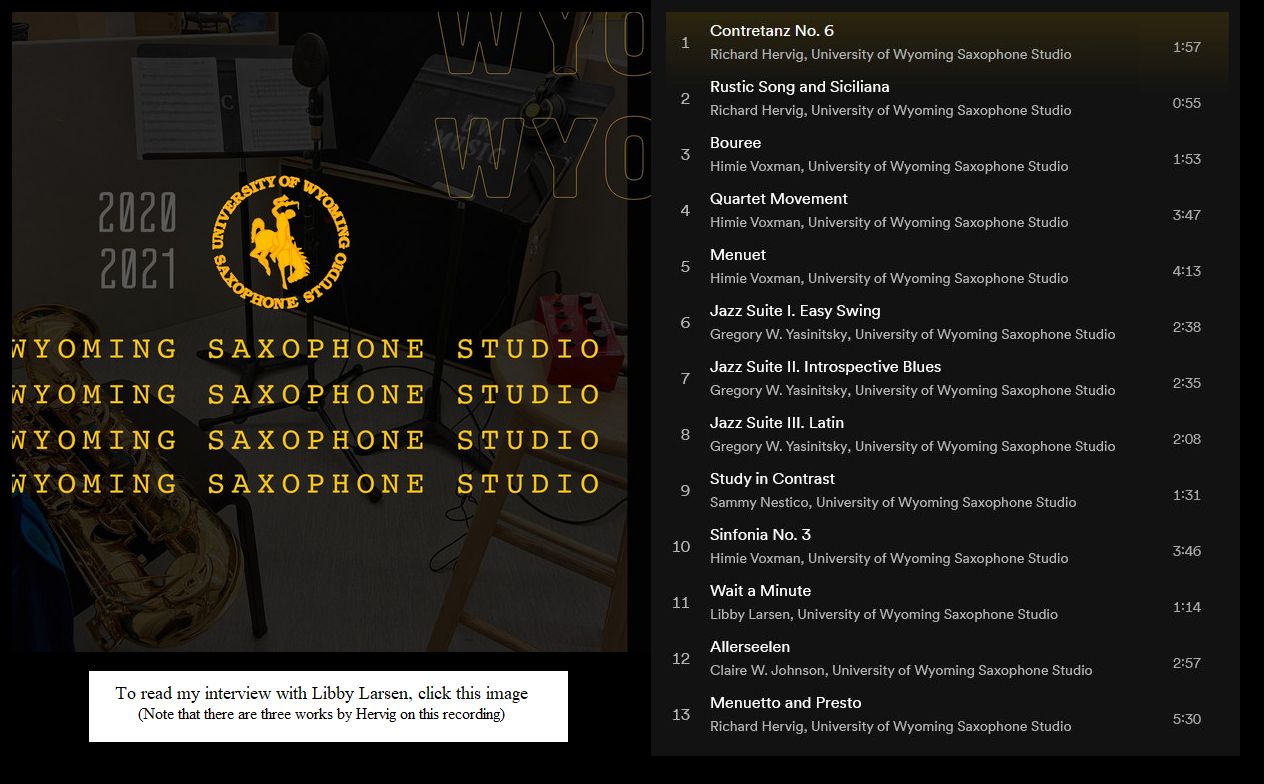

Richard Hervig was born in Iowa on November 24, 1917. Following a BA in

English (Augustana College, Sioux Falls, SD) and some high school teaching

(English and music) he studied composition with the late Philip Greeley

Clapp at the University of Iowa, receiving the MA in 1941 and PhD degrees

in 1947 in composition.

Richard Hervig was born in Iowa on November 24, 1917. Following a BA in

English (Augustana College, Sioux Falls, SD) and some high school teaching

(English and music) he studied composition with the late Philip Greeley

Clapp at the University of Iowa, receiving the MA in 1941 and PhD degrees

in 1947 in composition.

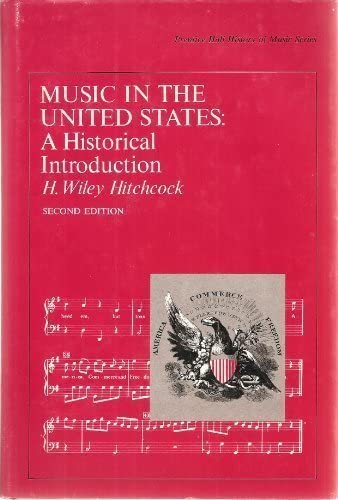

Hugh Wiley Hitchcock (September 28, 1923 in Detroit, Michigan

– December 5, 2007 in New York, New York) was an American musicologist.

He is best known for founding the Institute for Studies in American Music

at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York in 1971. The institute

was recently renamed the Hitchcock Institute for Studies in American Music

in his honor.

Hugh Wiley Hitchcock (September 28, 1923 in Detroit, Michigan

– December 5, 2007 in New York, New York) was an American musicologist.

He is best known for founding the Institute for Studies in American Music

at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York in 1971. The institute

was recently renamed the Hitchcock Institute for Studies in American Music

in his honor.

Bruce MacCombie (born December 5, 1943 in Providence, Rhode Island

died May 2, 2012 in Amherst, Massachusetts) was an American composer.

Bruce MacCombie (born December 5, 1943 in Providence, Rhode Island

died May 2, 2012 in Amherst, Massachusetts) was an American composer.  William Hibbard (August 8, 1939 - April 5, 1989)

William Hibbard (August 8, 1939 - April 5, 1989) Donald Martin Jenni (born Milwaukee, October 4, 1937 – died New Orleans

June 21, 2006) was an American composer, musicologist, and educator. A piano

and composition prodigy, Jenni began weekend studies with composer

Donald Martin Jenni (born Milwaukee, October 4, 1937 – died New Orleans

June 21, 2006) was an American composer, musicologist, and educator. A piano

and composition prodigy, Jenni began weekend studies with composer