Director Bodo Igesz

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

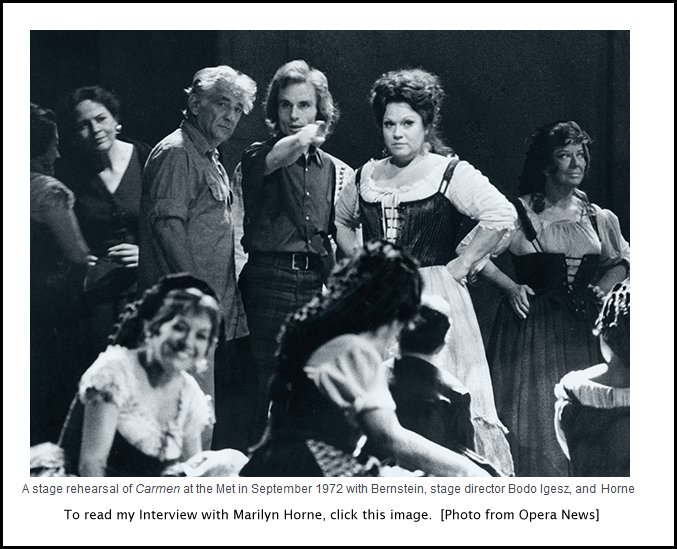

Bodo Igesz was in Chicago in February

of 1988 listening to auditions, and he graciously took time from a very busy

schedule to chat with me.

While setting up the tape machine to record our conversation, he spoke a

bit about his background. “I always had an interest

in languages, and at the University in Amsterdam I got interested in music

and drama and found the meeting place of those two. I used the scholarship

money to go to operas in Salzburg and Bayreuth and Paris and Berlin, as well

as seeing things in Amsterdam.”

As usual, names which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on this

website.

Here is the rest of our conversation . . . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: From

the viewpoint of the stage-director, where is opera going these days?

Bodo Igesz: Along

strange paths, I would say, very strange paths. I’m not very sure one

can say where opera is going at all, but I hope it’s going somewhere.

There are so many strange directions developing that you wonder sometimes

if it will even continue.

Duffie: [Genuinely

surprised] Really??? So you’re not optimistic about the future

of opera?

Igesz: Not so very

much. What you see happening at the moment in opera production is sometimes

the strangest ways of re-interpreting old repertoire which has to be found

because of the lack of new repertoire. That is a major problem.

Very few worthwhile new operas are appearing on the horizon, therefore the

direction that opera production takes is by hook or by crook trying to find

new hats for old people.

Duffie: Do you

enjoy looking for new hats?

Igesz: I do

enjoy it if a certain opera seems to be right for that new kind of hat.

What I think happens too often nowadays is that one chooses the hat first

and afterwards asks what is the opera, and that is backwards. What

you see happening often is that directors or designers have a specific style

that they neither adapt nor change for whatever opera they’re doing.

I have the greatest admiration for directors and designers who look at opera

first and ask what it is about, and look at its history, and then try to

find how to do it in the right way. It can be “right” for our time

or “right” for all time, but they should not be looking to do their own ideas

from this viewpoint or from that angle or in that style, and only afterwards

ask what is the opera. That’s not done so much here in the US, but

in Europe it happens an awful lot nowadays.

Duffie: Is there

any way to get more new operas written and presented?

Igesz: You can

give commissions, of course, but if you look at the lack of interest for

the few “popular” modern operas, you see how badly modern opera sells.

Especially in American there doesn’t seem to be much future for it.

Duffie: Is this

the fault of the composer or the performer or the public?

Igesz: It’s not

so much the fault of the public; I think it’s the whole development of music.

Look at symphony programs. You’re constantly re-hearing the same symphonies

of Brahms and Mozart and Schubert. I enjoy going to them no end, but

you don’t see anything new appearing that really has a following. Opera,

by necessity, needs a following because it costs an immense lot of money

to put it on, and it’s done in larger opera houses. That, I think,

is the crux of the matter. And because the same old repertoire keeps

being repeated, you get this attempt to present the old things from new angles.

There are only a few ways to do a piece that make sense.

Duffie: Do you

make sure everything you do makes sense on the stage?

Igesz: I always

try. If I have to do a certain opera, I start looking at the work...

Duffie: [Interrupting]

The music or the text?

Igesz: Both together,

and the background of the work. Then I try to find a style. I

don’t necessarily try to find a new style. If a new style presents

itself to me, fine, but I don’t admire those directors who look for a new

style at all costs. That is something that doesn’t work. If a

new line is the way to go, the new style will present itself to you.

But to say the opera, whatever opera you’re doing, must play on Mars or in

a steam bath, is very, very sad. Things like that have happened in

Europe.

Duffie: What is

the right direction for you?

Igesz: That’s a

very difficult question. The right direction to me is something that

for my eyes and my ears today makes sense to the opera in question.

Duffie: So you

re-examine it for each opera you do.

Igesz: Yes, absolutely.

Duffie: Then how

do you decide which operas you will accept to direct and which offers you

will let go to someone else?

Igesz: There are

certain things I rather accept, and other things I would rather not accept,

but my various bills must be paid each month. In general I am basically

interested in any kind of opera, and the more unusual the better. In

my career I’ve done pieces where the ink was still wet as I was staging them.

Sometimes the music was really awful, but thank God the libretto was wonderful,

so it was great to do. Since I’m not the most famous director in the

world, lots of bread-and-butter operas come my way, but I thank the Lord

when I can do something else. I enjoy doing Monteverdi and Cavalli,

as well as Berg and anything that I’ve not done in the last fifteen years.

As a stage-director, I always keep looking for the chance to do certain works.

Duffie: So even

if it was a standard work, if you hadn’t done it ever or in a long time,

you’d jump at the chance.

Igesz: Oh, of course!

There are some works you stage again and again, and others you wait for twenty

or thirty years to do. For example, I just came back from doing my

first Così Fan Tutte.

Duffie: Did you

put all the memories of having seen many performances of this opera to work,

or did you scrap those ideas and start completely fresh?

Igesz: I don’t

think you can scrap that, whether it’s been good or bad.

Duffie: So you

learn from others’ mistakes?

Igesz: Sure.

Duffie: And you

learn from others’ greatness?

Igesz: Absolutely.

I hope everyone does!

Duffie: Since you

mention Così, who winds up

with whom at the very end?

Igesz: That was

my first production, so the original couples wind up together. But

Così is a very subtle work,

and I don’t think you can put a very drastic ending to it. It wouldn’t

fit with either the libretto or the music. But at the very end, I had

the woman of one couple (Fiordiligi) and the man of the other couple (Ferrando)

look at one another and make a gesture to the public that indicated they

do not know what will happen in the future. That kind of subtlety is

right with Mozart.

Duffie: So it was

the right thing to end with a question mark?

Igesz: Exactly,

and the libretto gives no indication.

* *

* * *

Duffie: Since you

stage both old and new operas, is it more difficult to do a world premiere

because there is no point of reference?

Igesz: No, I don’t

think so. It might even be easier because you have nothing to fight

off. You start completely from scratch. No matter what opera

I am doing, I always have the memory of a production I’ve seen somewhere,

and even if you don’t follow the pattern, the good things you’ve seen will

always sneak themselves in somehow.

Duffie: And the

singers will mostly have sung the work under different directors.

Igesz: That I usually

don’t find to be a problem. Usually there are very interested in what

I have so say about the work. A major part of the work of a stage director

is to be a psychoanalyst, to work on the psyche of people to get them to

see things your way, and to make things work in a way that fits those people.

I’ve never had the experience of someone saying he couldn’t do it any other

way than what he’s done before. Especially in America, singers are

more than willing, even grateful for the chance to do something new, especially

if they’ve sung the work many times before.

Duffie: Do you

ever get too much rehearsal?

Igesz: Too much

rehearsal is worse than too little. I’ve never had too much.

I’ve learned how to make do with one week or with two weeks or with three

weeks or with whatever length of time there is. One time I had five

weeks and I thought it would be a luxury, but we just managed to get it ready

by the skin of our teeth. That was Henze’s The Young Lord, and it was the only time

where, in the fourth week, I thought it would not be ready for the opening.

Duffie: You work

with big, established stars in the major opera houses as well as with students

at the Music Academy of the West. What are the differences for you

in those two situations?

Igesz: I don’t

think that you can really generalize it. “Working with major stars

at the Met” really doesn’t exist. There is a vast difference between

working with Elisabeth

Söderström and with soprano X, and a vast difference between

working with José

van Dam and with baritone X. Singers can be difficult to work with

or are protected by management or things like that, but in my personal experience

that is very much the exception. The difference — which

is why working at the Music Academy of the West is so interesting

— is that you have the chance to discover roles with young singers

because you automatically get people who have absolutely never done anything

like it. When working in the big opera houses in Europe and America,

there are certain things you take for granted that you don’t even touch any

more. Suddenly, in order to take steps C and D, you have to teach steps

A and B, and that is nice.

Duffie: Now you’re

in Chicago listening to voices. What do you listen for?

Igesz: The musicians

from the Academy who are here with me listen to the voices. I also

listen to the voices, but I also look at how they present themselves and

how they would develop as actors and whether they would fit into our productions.

As you may know, Santa Barbara offers places for 20-22 singers, and since

we’re doing Britten’s Midsummer Night’s

Dream, most of the singers in our program will have to be in the production.

So we’re especially looking for a certain amount of men. I suggested

the opera, fully aware of the problems, including the need for counter-tenors!

When we put an ad in Opera News,

I asked that a note be included that counter-tenors could apply, and we’ve

had several audition! I was amazed and yet pleased, having originally

feared that we would have to get somebody from outside to do the role of Oberon.

Since the program is not only opera but also lieder interpretation and art songs,

we look for people who would benefit by joining the program in that department.

Duffie: Are the

applicants aware that a stage-director will be listening to the auditions

as well as just the musical staff?

Igesz: Probably,

since I’m listed as Director of Productions. They sing an aria of their

choice, and then give us a list of others from which we choose what we’d

like to hear. Naturally, whenever possible we choose to hear something

that will show different aspects of the voice. That can give a whole

different outlook on the possibilities of the individual.

Duffie: You then

work with the winners at the Academy?

Igesz: I just stage

the operas, but with each one double-cast and the singers taking voice lessons

as well as lieder classes, it takes

six to eight weeks to stage each opera.

Duffie: You’ve

also worked in Europe?

Igesz: I’ve worked

in Frankfurt and in my home country in Amsterdam as well as other towns in

Holland. I’ve also worked in South America, but because I live in New

York and I’ve been at the Met for many full seasons, most of my career has

been centered in this country. I started at the Met in 1963,

which means I did two seasons at the old house. The new house is a

big house, with all the advantages and disadvantages of a big house.

It no longer has the kind of “company” feeling that it once had. It

is constantly enlarging and getting to the point where it’s terribly impersonal,

and that’s not very good for an artistic company.

* *

* * *

Duffie: Are the

audiences different from country to country?

Igesz: Oh yes,

very much so. Until a few years ago, audiences were much more open

to new things in Europe than they were here. That is not necessarily

the audiences’ fault. There is much more introductory and preparatory

work done by publicity in European newspapers. I often try to convince

managers of regional companies to do lesser-known works, and they complain

that they can’t sell them. But I’ve found even here that if there is

enough publicity and lectures, and if the work is presented right and it

is worthwhile, it will sell.

Duffie: What makes

a work worthwhile?

Igesz: If it’s

something that works onstage, that works in the opera house either as music

or as drama or as both. There are certain works that audiences get

bored with, and for good reason. They are not strong works.

Duffie: Do you

shy away from those that don’t work so well?

Igesz: No.

I like to try and make them interesting. I did Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1975 in Central

City, Colorado. We sold out ten performances, and Colorado is not particularly

operatic minded. It was publicized. I would love to do one of

those wonderful Lortzing operas, but no manager with try it. They work

in Europe, and with a good translation could work well here. But managers

hesitate, and have a real fear of not selling. I think that fear is

exaggerated.

Duffie: Does opera

work well in translation?

Igesz: I’m not

against opera in English at all, as long as it’s a good translation.

Not those Ruth and Thomas Martin jobs, please. I’m not in favor of

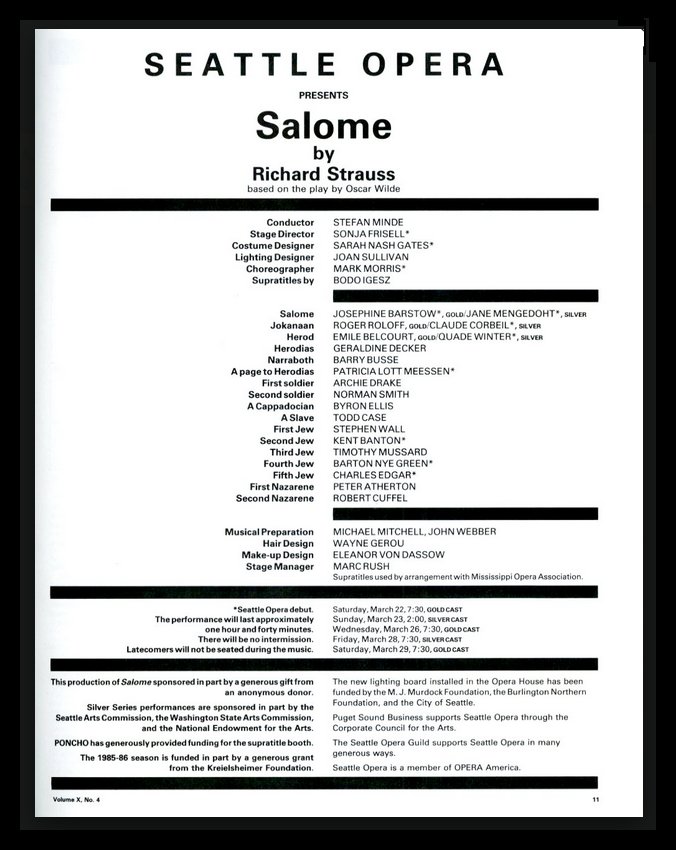

supertitles. They work for serious operas but not comic operas because

the pacing of the titles is different from the stage action. Having

said that, I should tell you that I make my own titles. That way I

have control as to what appears there. I’ve noticed that other translators

fail to take into account whether each title could be misinterpreted in a

funny or pornographic way. I speak French and Italian and German, so

it’s easy for me to say the titles are not needed, but I can see why the public

likes them.

Duffie: But you

spend your life working with this tradition and passing on these ideas.

What about the people who spend their time in other businesses and come to

the opera after a long hard day at work?

Igesz: The synopsis

and a good production should be all that is necessary. There are a

few exceptions, but in general, that should be enough. The idea of

using subtitles came first from movies and then from TV, but that’s a whole

different ball game. You are looking at the screen, and with the same

look you see the action. I know many singers who feel it’s an insult

to have these things flashing above them. On the other hand, I’m told

that the titles seem to have brought more and new public to the opera.

Duffie: The big

question, then. Is opera art or is it entertainment, and where is the

balance?

Igesz: It’s

both. For me, it’s 80% art.

Duffie: Even comic

operas?

Igesz: Yes, but

I’d rather have a good translation than titles. In serious operas,

it depends on how important the text is. You have to be so careful

what you translate for titles because much of what you translate is even

more ridiculous than the original. I know because I’ve done it!

[See program from Seattle Opera below.]

You can explain the story of Tosca

or Rigoletto or even Trovatore in a very tight synopsis.

Why do you have to understand every last word? Even if you speak fluent

Italian or whichever language the opera is in, you don’t understand every

last word.

Duffie: You don’t

feel it brings the audience closer and gives them an added dimension?

Igesz: It doesn’t

give it to me. I can do that at home with my record player. I

know I’m in the minority with that opinion, though some do agree with me.

Duffie: Of course

you’re working primarily for the Met, whose management has said there will

not be titles in their house.

Igesz: That has

nothing to do with it. I don’t speak for the Metropolitan. I

often disagree with the Metropolitan and they very often disagree with me.

I’m not sure that people get more out of opera now than they did twenty years

ago. It’s an acquired taste.

Duffie: Is opera

for everyone?

Igesz: No, I don’t

think so.

Duffie: Then what

is the purpose of opera in society?

Igesz: What is

the purpose of plays or concerts or football matches in society?

Duffie: [With mock

horror] Are you equating the Chicago Bears with the Lyric Opera???

Igesz: Some people

are as enthusiastic about the Bears as others are about Opera. That’s

everybody’s own personal choice. It’s interesting what you say.

What they’re trying to do with subtitles is to draw everybody into the theater

— even people who are not that interested in it. It’s wonderful

to sell seats, but maybe that is the wrong way.

Duffie: What’s

the right way?

Igesz: Doing good

productions and presenting works that get people interested! Do works

that are accessible, such as a good Fledermaus

or a good Abduction. Also

do youth programs and dress rehearsals for youthful audiences. It’s

difficult for me to discuss this because I’m from a European background.

It may be a little bit different here, but the whole thing gets much too

much stress at the moment. In the final analysis, they do more harm

than good.

* *

* * *

Duffie: Do you

think opera works well on the television?

Igesz: Certain

things, yes, especially the way the technique has gone ahead and the quality

of the TV broadcast has improved. It has the disadvantage of people

seeing that one Turandot or that

one Turn of the Screw and thinking

that is the way opera has to be. The same is true with audio recordings.

I have lots of records, and I prefer the “live” ones to the studio ones.

I like recordings and I like live performances in the theater, and you can’t

compare the two.

Duffie: Is there

anything you can do to streamline performances a bit?

Igesz: I like to

eliminate intermissions. The Marriage

of Figaro should be done with one intermission, and Bohème with two, not three.

But doing that depends on where the production is being given, and takes

a certain sophistication on the part of the audience. You can’t play

high-and-mighty and say the audience must sit for an hour and a half.

Festival situations are different from subscription evenings after workdays.

Duffie: What about

cuts in the music?

Igesz: That depends

on the conductor and the director. There are many cuts that are traditional.

They are done just because it’s always been done that way, and it’s wonderful

to open those cuts. Then there are cuts that have been made for a Very

Good Reason, often by the composer himself. We can judge these things

by performances that are now being given completely uncut, and you wonder

why on Earth must we do it with every repeat. It’s very nice for a

recording, but not in the opera house. That’s very personal and everybody

will judge it differently. When I begin working on an opera, I try

to look at the libretto as though I’ve never heard or seen it before.

That’s a very good standpoint from which to view the whole score. Then

when it comes to cuts, I ask if it adds to the performance to open the cut.

Duffie: How closely

do you work with the scenic designer?

Igesz: If it’s

a new production we work very closely. But these days with the lack

of money, regional companies don’t do many new productions. They will

rent a setting or use an existing set and change it around. That’s

sad. But to do a new production is wonderful, and for a stage director

it’s gourmet food.

Duffie: How closely

do you work with the lighting designer?

Igesz: Usually

very closely. The ideal situation is when the set designer is also

a very good lighting designer. I’ve done many new productions with

someone who did both, and it produced wonderful results. But I must

say that today there are many fabulous lighting designers. I grew up

at a time when Europe was discovering that lighting could take the place

of 50% of the scenery, and I’m very much of that belief. If you have

a really good lighting designer, you can come out with a far smaller budget

for scenery.

Duffie: Projections,

too?

Igesz: Oh yes,

definitely.

Duffie: What advice

do you have for someone coming along who wants to be an operatic stage director?

Igesz: Try to find

a really fantastic stage director whom you can assist in a theater for a

few years. I’ve worked with Zeffirelli, but I learned from only one

man — Gunther Rennert. He would meet an opera

on its own terms.

Duffie: Would you

allow someone to apprentice themselves to you?

Igesz: Yes, but

I would not advise that. I’m not that great. I have people asking

me, but I’m not so filled with ego. I can do very good productions

and I have a good knack for working with people, and it happens from time

to time that I will let someone work with me for a while, but I don’t pretend

to be someone at the highest level.

Duffie: Is directing

fun?

Igesz: Yes.

It can be bloody murder, but to me it’s mostly fun. Otherwise, I wouldn’t

have stuck with it for thirty years.

Duffie: Do you

have any advice for young singers?

Igesz: Try to get

somewhere and find a company who will hire you on a season’s basis.

Not a huge house like the Met, but one where you can sing a lot of big roles

and small roles during the season to learn. The Lyric Opera Center

for American Artists is great. Then don’t shout it all away

in the first five years of what could have been a forty year career.

That happens so often. Get experience, and for Heaven’s

sake, get your languages together. There are so few people who really

know how to do French, Italian and German. I’ve seen works in Swedish

or Russian or Czech — that I don’t speak

— and I take the trouble to read the synopsis in an opera guide

that I have. I also read the program. Until recently, nobody

in Europe would dream of having subtitles in the opera like they were in

movies. I find that for myself, I get the very best results when I

do a work — any work, old or new — for

the first time. A second production of something will never be as good

as the first one. Somehow I fail to bring that kind of freshness to

it. Opera is a conglomerate effort — singers,

designers, conductor, director. The stage director can be over-accentuated

these days sometimes. I’m not doing MY opera, but rather the COMPOSER’S

opera. It’s as I see it, but it is the composer’s opera. To prepare

a production, I work very hard at home and write down everything I want to

do.

Duffie: Then do

you slavishly stay with that?

Igesz: I stay slavishly

with the general concept and embroider onto that. My experience is

that singers are intensely grateful if you work with them like that.

Singers have the responsibility to know what is in the score when he comes

to rehearsal. A director, unless he is a Brilliant Improviser, must

have a certain detailed idea of what he’s going to do. Singers have

told me horror stories of working with directors who block scenes and then

after a few days re-block, and later re-block again. They arrive without

the foggiest notion of what they’re going to do. Problems have to be

worked out ahead of time, unless something just doesn’t go well.

Duffie: Do you

capitalize on the strengths and weaknesses of the singers?

Igesz: Oh yes,

definitely. And having worked with many of the artists, I will know

some of that in advance. The world of opera is not so big, and if you

don’t know someone, you don’t plan something terribly tricky. You can

always add more if the singers are up to it.

Duffie: Do you

have any advice for the established singers?

Igesz: Life is

going too fast, especially for musicians. You have to get there the

next day instead of growing slowly. I’m always intensely happy to meet

a singer who says he was offered a role and told them maybe in 15 years.

Thank Heavens, somebody who thinks. I also did plays early

on in my career, but I am very happy doing operas as long as the general

working atmosphere is nice, and usually it is.

I’m not a frustrated conductor, but my hobby, when listening to broadcasts

and recordings is conducting.

Duffie: Does that

make it better when you’re communicating with the conductor on a production?

Igesz: Oh yes.

I think so. I hope so.

Duffie: Is it at

all frustrating to work every day until the premiere and then leave town?

Igesz: Yes.

It’s always a letdown. On the other hand, you don’t have to see your

product disintegrate after a few performances, which often happens.

Duffie: Do you

come back after the third or sixth performance and do a little touchup or

scream a bit?

Igesz: [Laughs]

Well, you don’t have to scream, but I give notes. Usually the first,

second and third performances are the best of the production in the opera

world. It’s different if you have an ensemble theater and a cast that

is the same throughout.

Duffie: I would

think a new cast member might keep everyone on their toes.

Igesz: Yes, but

it’s not the way to keep a wonderful production alive.

=======

======= =======

======= =======

---- ---- ---- ----

----

======= =======

======= =======

=======

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on February 13, 1988.

The transcription was made and published in The Opera Journal in March, 1995.

It was slightly re-edited, the photos, links and biography were added, and

it was posted on this website in 2016.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here.

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago

from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001.

His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since

1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well

as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other

interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call

your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with

comments, questions and suggestions.