Geraldine Decker (March 11, 1931,

New York City — June 14, 2013, Oxnard, California) was an American mezzo-contralto

and voice teacher who had active singing career in operas and concerts from

1971 through 2010. She was particularly active with the Metropolitan Opera

and the Seattle Opera, and is best remembered for her annual performances

in Seattle of Richard Wagner's Ring

cycle from 1974-1987. She taught on the voice faculty of Pepperdine University. Born Geraldine Helen Rice in the Bronx, Decker moved with her family to California

in her youth. She attended Corvallis High School in Studio City, California

from 1945 to 1949. She soon after married her husband of 55 years, Howard

Decker, with whom she had two sons, Wayne and Dirk Decker. While raising

her children she pursued studies in voice with Dr. Nandor Domokos in Los

Angeles. She later studied with Luisa Franceschi and her husband, baritone

Ellae Verna, in New York City.

Born Geraldine Helen Rice in the Bronx, Decker moved with her family to California

in her youth. She attended Corvallis High School in Studio City, California

from 1945 to 1949. She soon after married her husband of 55 years, Howard

Decker, with whom she had two sons, Wayne and Dirk Decker. While raising

her children she pursued studies in voice with Dr. Nandor Domokos in Los

Angeles. She later studied with Luisa Franceschi and her husband, baritone

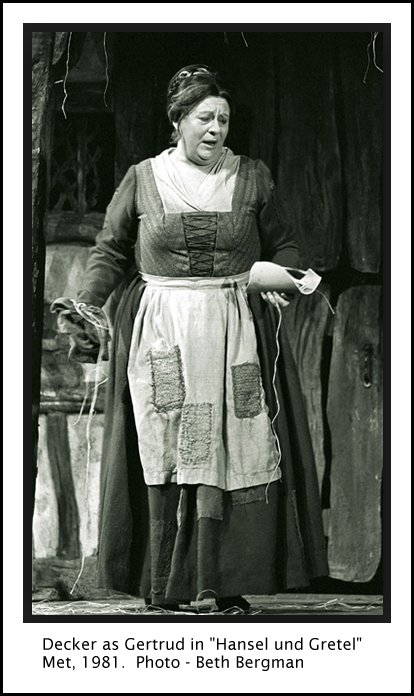

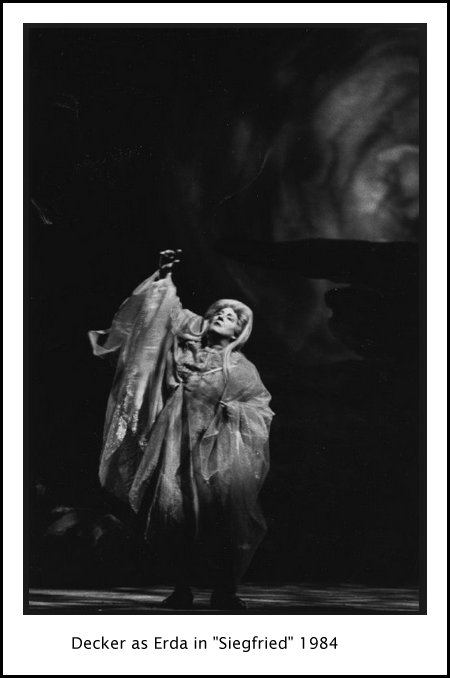

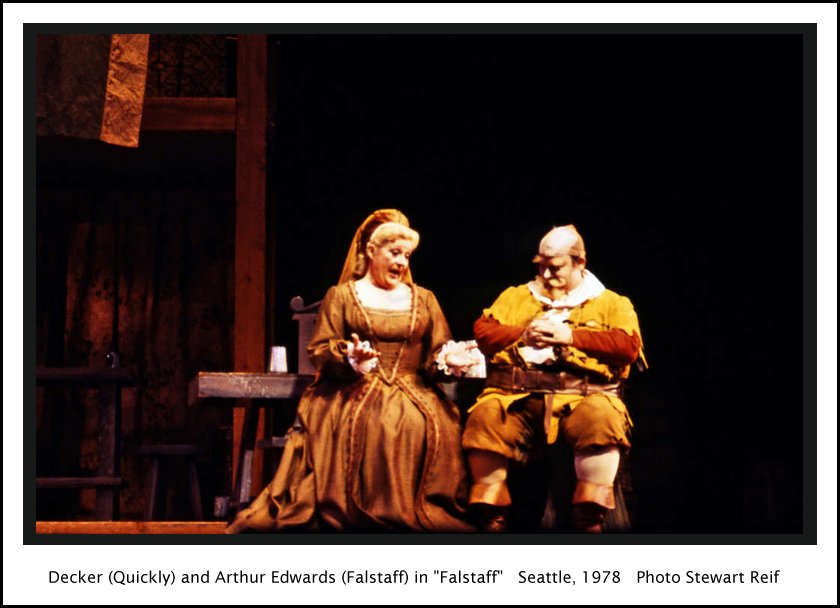

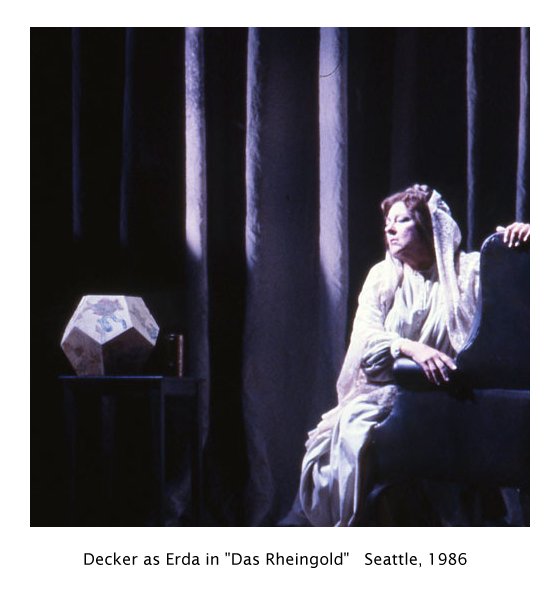

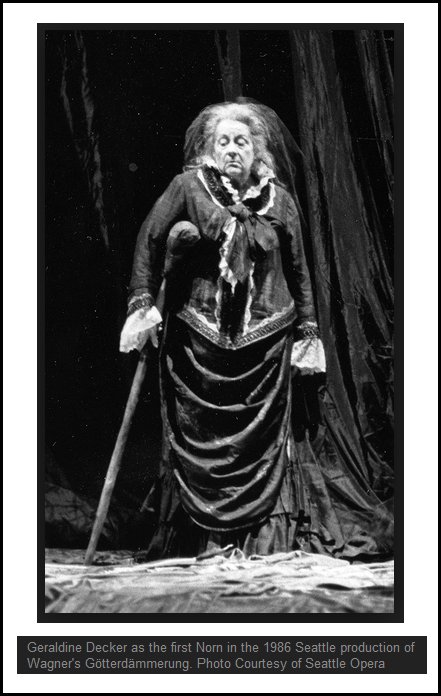

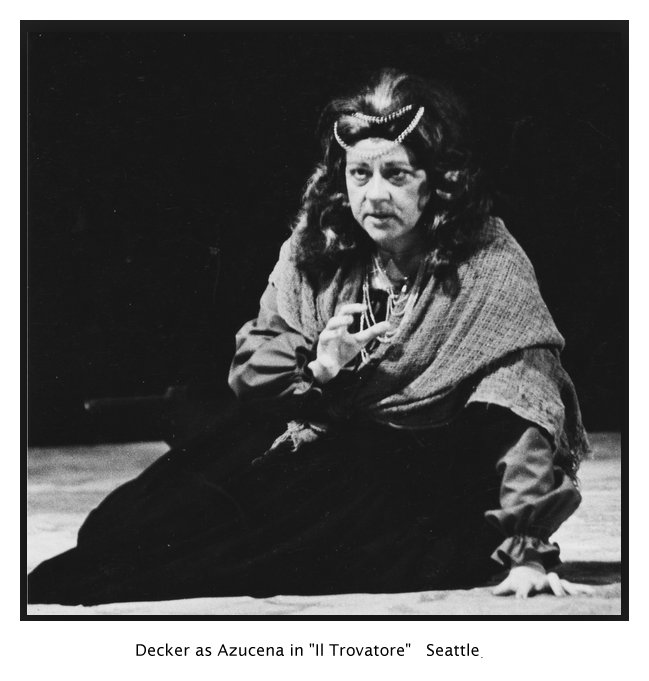

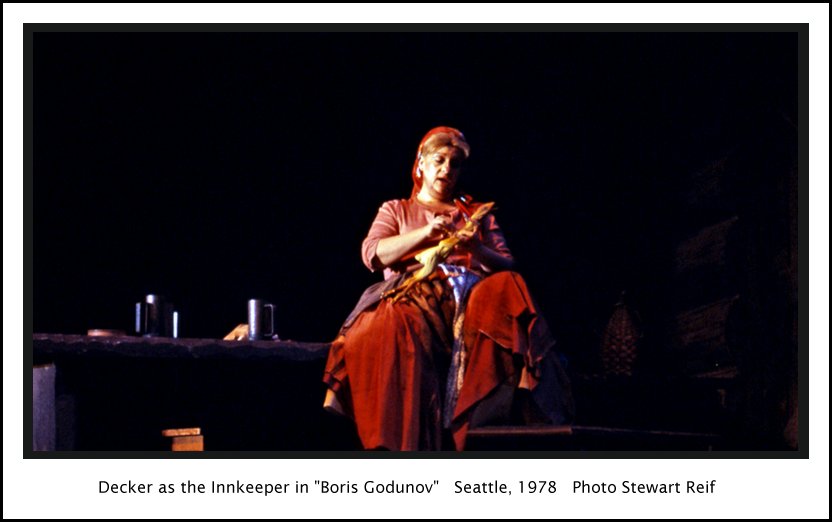

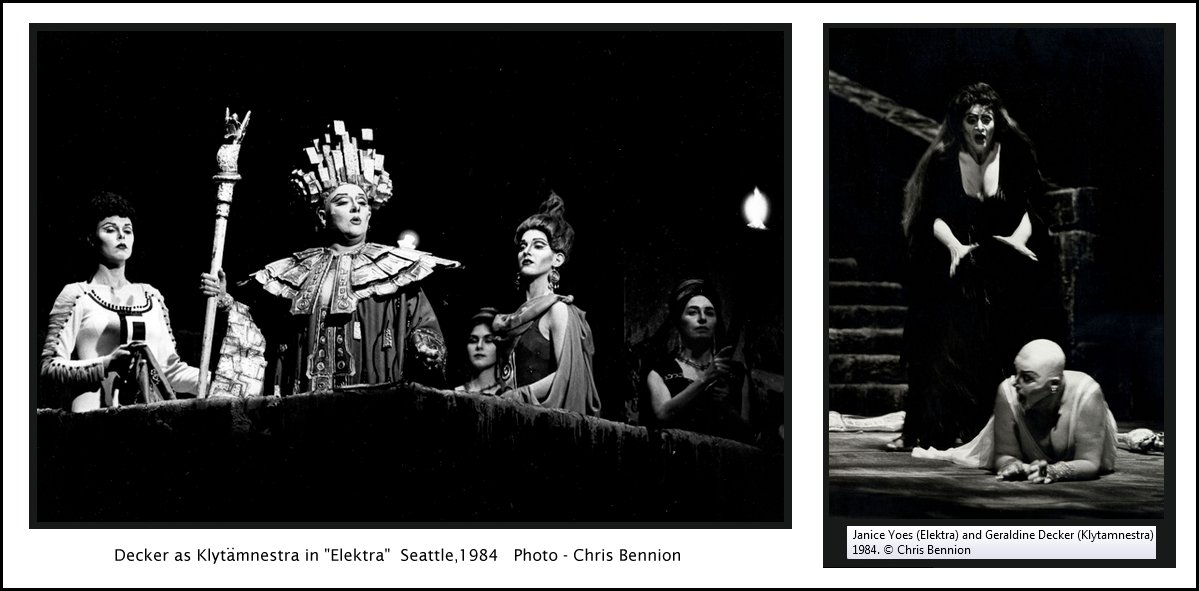

Ellae Verna, in New York City.After her sons were grown and had moved out of the family home, Decker began pursuing a career in opera, devoting the next two decades of her life to it. She first drew critical notice in 1974 at the Seattle Opera where she appeared as Erda in both Das Rheingold and Siegfried, Schwertleite in Die Walküre, and the First Norn Götterdämmerung. She portrayed those roles again in Seattle every summer through 1987, as well as many other roles at the Seattle Opera, including Albine in Massenet's Thaïs, Azucena in Verdi's Il trovatore, Filippyevna in Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin, Grandmother Burja in Janáček's Jenůfa, Herodias in Strauss' Salome, Klytämnestra in Strauss' Elektra, Mama McCourt in Moore's The Ballad of Baby Doe, Marthe Schwerlein in Gounod's Faust, Mistress Quickly in Verdi's Falstaff, Mother Jeanne in Poulenc's Dialogues of the Carmelites, and the Nurse/Innkeeper in Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov. Decker made her debut at the Lyric Opera of Chicago in 1978 as Mamma Lucia in Mascagni's Cavalleria rusticana. On December 17, 1980 she sang the same role for her debut at the Metropolitan Opera with Grace Bumbry as Santuzza and David Stivender conducting. She was a regular presence on the Met stage for six seasons, portraying such roles as Gertrud in Humperdinck's Hansel and Gretel, Gertrude in Gounod's Roméo et Juliette (with Placido Domingo conducting), Grandmother Burja in Jenůfa, and Schwertleite in Die Walküre among others. In 1981 she portrayed the Large Woman in the Met premiere of Les Mamelles de Tirésias, and was also seen that year as Annina in the premiere of the Colin Graham staging of Verdi's La traviata; a production which was broadcast nationally on Live from the Met. Her last performance at the Met was as the Nurse in Boris Godunov on March 23, 1987 with Paul Plishka in the title role and James Conlon conducting. In 1982 Decker created the role of Nelly Dean in the world premiere of Bernard Herrmann's Wuthering Heights at the Portland Opera. That same year she appeared in Franco Zeffirelli's film version of La Traviata. Other companies she performed roles with during her career included Cabrillo Music Theatre, Hawaii Opera Theater, the Long Beach Opera, the Los Angeles Civic Light Opera, and Opera San José. In 1990 she portrayed Mrs. Beemer in the Disney film Polly: Comin' Home! She also appeared as a maid in the 1976 film Harry and Walter Go to New York. Decker lived in Oxnard, California for over 50 years. She died there in 2013 at the age 82 from complications of diabetes. == Names which are links refer to my interviews

elsewhere on my website. BD

|

BD: I was amazed at

how many of the words I understood in the theater. I assume that everyone

works very hard on articulation?

BD: I was amazed at

how many of the words I understood in the theater. I assume that everyone

works very hard on articulation?

BD:

Does everyone get that involved with the experience of Wagner

— even the guys who pound nails backstage?

BD:

Does everyone get that involved with the experience of Wagner

— even the guys who pound nails backstage? BD: A lot of the orchestra is back, under the stage

and that helps the balance.

BD: A lot of the orchestra is back, under the stage

and that helps the balance. BD: How do you find shifting from Herodias to Azucena?

BD: How do you find shifting from Herodias to Azucena?

© 1979 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in her hotel in Chicago in October,

1979. It was partially transcribed, and the Wagner portions were published

in Wagner News in the Summer Issue

of 1981. The transcript was completed and re-edited, the bio, photos

and links were added and it was posted on this website early in 2016.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.