JK: They sometimes don’t become musically trained

well enough, and they are not good enough in their languages. Pavarotti

sings every night in his mother tongue, but we Americans, and the English

and the Scandinavians have to learn these foreign languages, and we really

don’t get much credit for it. There’s only one Italian singer that

I ever heard that could sing in a foreign language and that was Cesare Siepi.

I heard many of them sing. They try to sing French and they do a fair

job, but there are mistakes, generally, in the French. It’s a totally

different world from Italian, but we have to do it. It’s got to be

right or they’re not going to engage us for certain things, and certainly

not for recordings. Thank God I had a wonderful teacher at LSU in the

forties when I started studying there. His name was Dallas Draper,

and he insisted that I take two semesters each of German, French and Italian.

I hated it at the time, but it gave me a basis that I am eternally grateful

for! He himself was not such a good linguist, and he wanted to be sure

that I made up for what he had missed. He was a wonderful singer and

a fine teacher! He got me on the right track when I was doing really

rather poorly. That basis in language really set me up for the world.

Then I went into teaching after I got my master’s degree in ‘52. I

taught singing at the University of Kentucky for nine years, until ‘61.

JK: They sometimes don’t become musically trained

well enough, and they are not good enough in their languages. Pavarotti

sings every night in his mother tongue, but we Americans, and the English

and the Scandinavians have to learn these foreign languages, and we really

don’t get much credit for it. There’s only one Italian singer that

I ever heard that could sing in a foreign language and that was Cesare Siepi.

I heard many of them sing. They try to sing French and they do a fair

job, but there are mistakes, generally, in the French. It’s a totally

different world from Italian, but we have to do it. It’s got to be

right or they’re not going to engage us for certain things, and certainly

not for recordings. Thank God I had a wonderful teacher at LSU in the

forties when I started studying there. His name was Dallas Draper,

and he insisted that I take two semesters each of German, French and Italian.

I hated it at the time, but it gave me a basis that I am eternally grateful

for! He himself was not such a good linguist, and he wanted to be sure

that I made up for what he had missed. He was a wonderful singer and

a fine teacher! He got me on the right track when I was doing really

rather poorly. That basis in language really set me up for the world.

Then I went into teaching after I got my master’s degree in ‘52. I

taught singing at the University of Kentucky for nine years, until ‘61. JK: I was kept in my fach. They looked after me, I must

say. The first year I was there I sang fifty performances. I

came with only three roles in my repertoire — Don José

in Carmen, Bacchus in Ariadne, and Cavaradossi. They

didn’t do any Toscas, but that first

year they had me learn Ballo in Maschera,

and I had to relearn Carmen in German.

Then in the summer I went to Salzburg, and was asked to jump in for Konya

and do Iphigénie en Aulide

of Gluck, which was a great opera. I’m sorry we don’t hear more Gluck

in this country. It’s a fine work.

JK: I was kept in my fach. They looked after me, I must

say. The first year I was there I sang fifty performances. I

came with only three roles in my repertoire — Don José

in Carmen, Bacchus in Ariadne, and Cavaradossi. They

didn’t do any Toscas, but that first

year they had me learn Ballo in Maschera,

and I had to relearn Carmen in German.

Then in the summer I went to Salzburg, and was asked to jump in for Konya

and do Iphigénie en Aulide

of Gluck, which was a great opera. I’m sorry we don’t hear more Gluck

in this country. It’s a fine work. JK: Of course you have to try to sing well and you

have to be sure that that’s working right, and that does take our minds’

being occupied in that respect. I have to watch the conductor sometimes.

I can’t just stand there and sing for myself alone. I have to be in

contact with the orchestra and with him. Maybe his tempi

are a little different than my conception, and I have to adjust to that.

I have to go a little faster or a little slower, maybe, than I’ve been used

to. So it’s always necessary to be perfectly in contact with your conductor,

even though you may be looking around trying to act. But you learn

to cover up for it, to fake it, and to make it look like it’s intended to

be that you look the way you look.

JK: Of course you have to try to sing well and you

have to be sure that that’s working right, and that does take our minds’

being occupied in that respect. I have to watch the conductor sometimes.

I can’t just stand there and sing for myself alone. I have to be in

contact with the orchestra and with him. Maybe his tempi

are a little different than my conception, and I have to adjust to that.

I have to go a little faster or a little slower, maybe, than I’ve been used

to. So it’s always necessary to be perfectly in contact with your conductor,

even though you may be looking around trying to act. But you learn

to cover up for it, to fake it, and to make it look like it’s intended to

be that you look the way you look. JK: Not really, no. I suffer a little bit

on recordings. Birgit

Nilsson said this, too. She said, “Jimmy, we have these heavy voices,

and the microphones immediately turn us down when we sing a little bit too

loudly.” It’s automatically done, and unless they go through those

recordings and adjust the volume of your voice, you sound just like the others.

I remember the only time I ever had a high C on a recording, except for the

Frau ohne Schatten, was Butterfly, which I recorded with Maria

Chiara. I also recorded the Butterfly

duet with Anna Moffo

in the Olympic year in Munich. In both of them you can’t hear my high

C.

JK: Not really, no. I suffer a little bit

on recordings. Birgit

Nilsson said this, too. She said, “Jimmy, we have these heavy voices,

and the microphones immediately turn us down when we sing a little bit too

loudly.” It’s automatically done, and unless they go through those

recordings and adjust the volume of your voice, you sound just like the others.

I remember the only time I ever had a high C on a recording, except for the

Frau ohne Schatten, was Butterfly, which I recorded with Maria

Chiara. I also recorded the Butterfly

duet with Anna Moffo

in the Olympic year in Munich. In both of them you can’t hear my high

C.  BD: They’ll never get the fiddle players and the

wind players to agree to lower the pitch.

BD: They’ll never get the fiddle players and the

wind players to agree to lower the pitch. JK: I guess we just can’t see enough. It’s

too nebulous; it’s too vague; it’s too obscure; it’s too difficult to see.

You can’t tell, for example, how much pressure a singer is giving with his

breath. The big deal is to learn to balance the pressure of the breath

against the vocal cords, and you can’t measure that. If you give

a little bit too much, then the vocal cords start resisting the breath more.

That makes them get a little thicker, and you may have a tone that’s produced

with cords that are used for a lower tone. You’re trying to get a higher

tone out of them simply because you haven’t the coordination or the balance

of the breath energy. The real trick is the breath. The only

way a singer learns that is just to work on himself long enough until he

begins to sense it. That’s what I did. Singing for me has never

been easy. I know I was highly talented and I loved the work, but it

took me forever to get things really right. It’s the lack of proper

instincts for the function of the breath which brings us into the troubles,

and until you feel it perfectly, with the workings of the diaphragm and the

sound of the tone buzzing in your head, you’re not going to sing right.

Then you’ve got to do all the things like color the voice and bring interpretation

with the dynamics to make it louder and softer. It was in October last

year when I did Ariadne at the Met

that I felt I was getting into vocal trouble. I had done Salome in San Francisco and I said, “Well,

I’m sixty-two years old. It’s about time I was giving it up anyway.”

So I went to a teacher in New York and I said, “I’m having a little trouble

with my high notes. I’m not as good as I was. I have to expect

it at my age.” He said, “Well, let’s work a while.” So I took

six lessons from this man, and he put his finger on something that I was

doing wrong. I went to work on it and I got better and better and better,

and since then I haven’t had one problem with my high notes! I sang

Die Liebe der Danae, and it had

six B-naturals in it! It was real Pavarotti territory. I sang

five performances and never missed a one, and I had sung four weeks of rehearsals

before we did it in Munich this summer. I must have sung a hundred

and twenty B-naturals in that period and I never cracked on one. I

had a little problem of letting my larynx creep up too high, and that was

what was doing it. I used to crack now and then when singing Bacchus;

you know how excruciatingly high it is! Now I got through all of those

performances. The television broadcast of our Ariadne at the Met with Jesse Norman

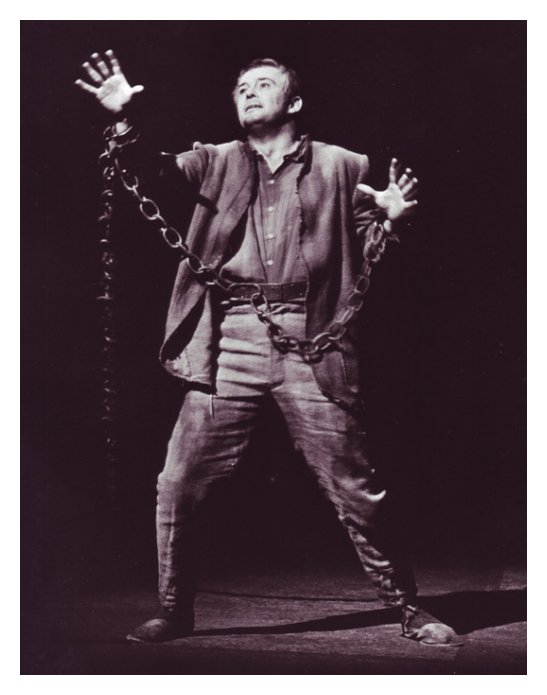

went so well. [Photo at left]

JK: I guess we just can’t see enough. It’s

too nebulous; it’s too vague; it’s too obscure; it’s too difficult to see.

You can’t tell, for example, how much pressure a singer is giving with his

breath. The big deal is to learn to balance the pressure of the breath

against the vocal cords, and you can’t measure that. If you give

a little bit too much, then the vocal cords start resisting the breath more.

That makes them get a little thicker, and you may have a tone that’s produced

with cords that are used for a lower tone. You’re trying to get a higher

tone out of them simply because you haven’t the coordination or the balance

of the breath energy. The real trick is the breath. The only

way a singer learns that is just to work on himself long enough until he

begins to sense it. That’s what I did. Singing for me has never

been easy. I know I was highly talented and I loved the work, but it

took me forever to get things really right. It’s the lack of proper

instincts for the function of the breath which brings us into the troubles,

and until you feel it perfectly, with the workings of the diaphragm and the

sound of the tone buzzing in your head, you’re not going to sing right.

Then you’ve got to do all the things like color the voice and bring interpretation

with the dynamics to make it louder and softer. It was in October last

year when I did Ariadne at the Met

that I felt I was getting into vocal trouble. I had done Salome in San Francisco and I said, “Well,

I’m sixty-two years old. It’s about time I was giving it up anyway.”

So I went to a teacher in New York and I said, “I’m having a little trouble

with my high notes. I’m not as good as I was. I have to expect

it at my age.” He said, “Well, let’s work a while.” So I took

six lessons from this man, and he put his finger on something that I was

doing wrong. I went to work on it and I got better and better and better,

and since then I haven’t had one problem with my high notes! I sang

Die Liebe der Danae, and it had

six B-naturals in it! It was real Pavarotti territory. I sang

five performances and never missed a one, and I had sung four weeks of rehearsals

before we did it in Munich this summer. I must have sung a hundred

and twenty B-naturals in that period and I never cracked on one. I

had a little problem of letting my larynx creep up too high, and that was

what was doing it. I used to crack now and then when singing Bacchus;

you know how excruciatingly high it is! Now I got through all of those

performances. The television broadcast of our Ariadne at the Met with Jesse Norman

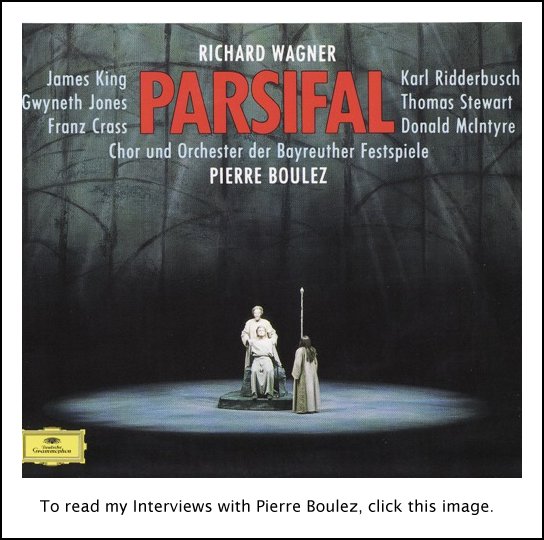

went so well. [Photo at left] BD: Let me ask you about another Wagner opera,

Parsifal. Is this a sacred

work, or is this just another opera?

BD: Let me ask you about another Wagner opera,

Parsifal. Is this a sacred

work, or is this just another opera? JK: I sang sixty to sixty-five performances a year

on the average. Then with all the rehearsals and traveling, it was plenty.

I tried to sing no more than twice a week and have two days between performances,

always. If you’re doing Tristan, one a week is enough, I’m sure.

You need at least three days for those vocal cords to settle down after a

performance like that. Four would be better, or a whole week would

be even better.

JK: I sang sixty to sixty-five performances a year

on the average. Then with all the rehearsals and traveling, it was plenty.

I tried to sing no more than twice a week and have two days between performances,

always. If you’re doing Tristan, one a week is enough, I’m sure.

You need at least three days for those vocal cords to settle down after a

performance like that. Four would be better, or a whole week would

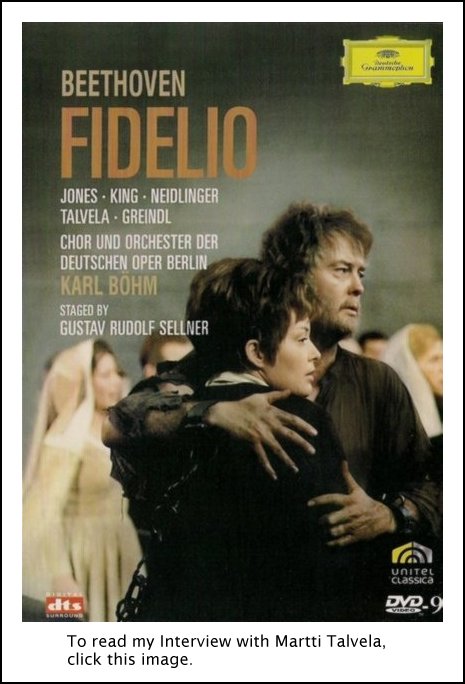

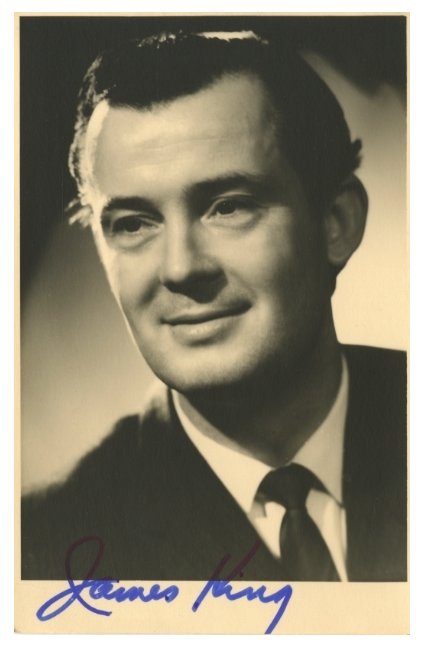

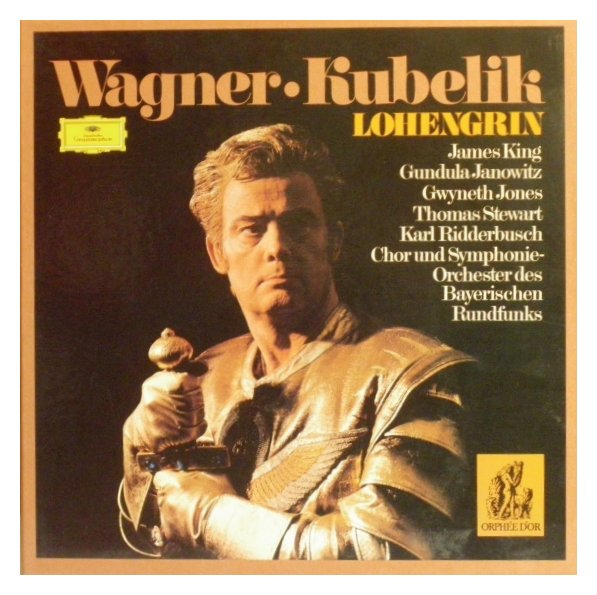

be even better.Obituary James King Distinguished tenor at ease in the operas of Wagner and Strauss Alan Blyth The Guardian Tuesday 22 November 2005 The American James King, who has died aged 80, was among the foremost heroic tenors of the latter part of the 20th century, particularly noted for his singing of the strenuous roles in Wagner and Richard Strauss operas. At a time when such singers were in very short supply, he was in continuous demand, extending a busy career well into his 60s. Born in Kansas, he was brought up by poor parents, a hard-drinking Irish father and a mother of German descent. Music caught his ear as he listened to popular singers on the radio, such as Nelson Eddy and Grace Moore. From the age of nine, he learnt the violin and sang in church choirs. After wartime military service, he studied at Louisiana State University with Dallas Draper, who made him learn languages in addition to singing. A baritone at that time, he sang major roles for the opera department. After graduation in 1949, King taught for nine years at the University of Kansas City, where he gave recitals. In 1956, realising he was a tenor, he retrained, notably with the baritone Martial Singher, to whom he said he owed the inception of his career. After a sabbatical devoted to study, in 1960 he became resident tenor with the Saint Louis Municipal Opera. From then on, his rise was swift. His real break came in May 1961, when he sang Don José to Marilyn Horne's Carmen at the San Francisco Opera to notable acclaim. Bacchus, in Strauss's Ariadne auf Naxos, soon to be one of his most important assumptions, followed at the Cincinnati summer festival. Then, after an exhaustive audition singing many arias, he was asked to join the Deutsche Oper, in Berlin, as principal tenor. In his first year there, he sang 50 performances of an extensive repertory, including his first Florestan, in Fidelio. In 1963, he sang his first Lohengrin, destined to become one of his favourite and most successful parts. That year he also made his debut at the Vienna State Opera. Bacchus was his debut part, and he sang it again in Munich in 1964, the year of the Strauss centenary. King was ideal, managing to be Ariadne's heroic rescuer, while suggesting the slightly ridiculous element in the part. His strong, trumpet-like voice was perfect for a role he sang for many years, notably in 1972, when the Bavarian State Opera visited Covent Garden. Back in Berlin he also undertook the Emperor, in Strauss's Die Frau ohne Schatten, another taxing part for a tenor. King was totally unfazed by its high tessitura and exigent demands on his voice. He sang it with success at both the Metropolitan and Covent Garden. Another role in which he excelled was Apollo, in Daphne. All these evinced the extraordinary stamina of King's vocal makeup. In the following months he also sang, for the first time, Calaf in Turandot, the title role in Don Carlos and Siegmund in Die Walküre, which he also sang at his Bayreuth debut in 1965 (and recorded under Solti). That became one of the most noted of his Wagnerian assumptions, along with his Walther, in Die Meistersinger and Parsifal. By this time, he had moved from Berlin to the Bavarian State Opera in Munich, where he remained for the rest of his career. His Metropolitan debut came in 1966 as Florestan, and he sang intermittently at Covent Garden in his Wagner and Strauss roles, 1966-76, though the main part of his career was on the continent. Italian parts such as Canio, in Pagliacci, Manrico, in Trovatore, Radames, in Aïda, and Otello featured in his repertory, but he tended to be asked more and more for his German parts. In his later career, he was admired as Pfitzner's Palestrina, Aegist in Strauss's Elektra, Captain Vere in Britten's Billy Budd (San Francisco, 1985), Paul in Korngold's Die Tote Stadt (Berlin, 1983), and the Drum-Major in Berg's Wozzeck (Vienna 1981, Covent Garden, 1984, Metropolitan, 1990). Although he never officially retired, his career effectively ended in the mid-1990s, after which he continued the teaching he had already begun part-time at the University of Indiana. King's long and successful career was based on the solidity of his singing allied to innate musicianship. Although he never gave an overwhelming performance, he could always be relied upon to deliver a thoughtful and reliable one. He was perhaps best suited by Florestan, Lohengrin, Parsifal and Bacchus, all of which are preserved on disc. Today, when his kind of voice is even harder to find, his achievement seems in retrospect all the more significant. · James King, tenor, born May 22 1925; died November 20 2005 |

James King, 80, Tenor Known for Strauss and Wagner, DiesBy Wolfgang Saxon The cause was a heart attack, according to Indiana University, where he taught music and voice from 1984 to 2002. His death was first announced by the Vienna Staatsoper, of which he was an honorary member. It was also noted by the Deutsche Oper in Berlin, where he had his first resident appointment in 1962 as a nearly unknown singer from the United States, and at the Metropolitan Opera, where he took on some of the most challenging tenor roles. Mr. King won acclaim for roles by Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss, composers in whom he specialized. At the Met, he made his debut in 1966 as Florestan in Beethoven's "Fidelio," the first of 113 appearances there. He set records for the most performances in two particularly demanding roles on the Met roster, Bacchus in Strauss's "Ariadne auf Naxos" and the Emperor in "Die Frau Ohne Schatten," a role he sang in the opera's Met premier. Met audiences also heard him in works by Berg, Bizet, Britten, Puccini and Wagner. His final performance was in 2000 at Indiana University in a production of Wagner's "Walküre," in which he took the role of Siegmund. James King was born in Dodge City, Kan., to an Irish father and a mother of German descent. As a boy he learned to play the violin and sang in church choirs. He studied music at the University of Missouri, Kansas City, earning a master's degree, and started out as a baritone before training as a tenor with Martial Singher in New York, and with Max Lorenz. Keeping a baritone quality in his lower notes, he acquired a distinctive, recognizable timbre that assured him a long career. His voice was described as strong and dependable, with the stamina to sustain him in longer dramatic roles, and his six feet of height added impact to his performances. Howard Klein of The New York Times, welcoming him as the Met's Florestan in 1966, hailed him as "among the few tenors around today who can fill the role" and still have "plenty of voice to spare." James King won an American Opera Audition held in Cincinnati in 1961 and went in search of a career in Europe, as did many budding American singers at the time. His professional debut was as Cavaradossi in Puccini's "Tosca" at the Teatro della Pergola in Florence. He repeated the role at the Teatro Nuovo in Milan, gaining his first resident appointment in Berlin with a debut as the Italian tenor in "Der Rosenkavalier." Over the years he also sang at London's Royal Opera House, in Salzburg and at the Bayreuth Festival; and in Cincinnati, San Francisco and Philadelphia in the United States. He starred in German opera films, regularly sang in radio and television productions of opera, and made recordings under Sir Georg Solti and Karl Böhm. His survivors include his third wife, Elizabeth; three sons; and two daughters. |

This interview was recorded at his hotel in Chicago on December 9, 1988. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1989, 1993, 1995, 1997, and 2000. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.