A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

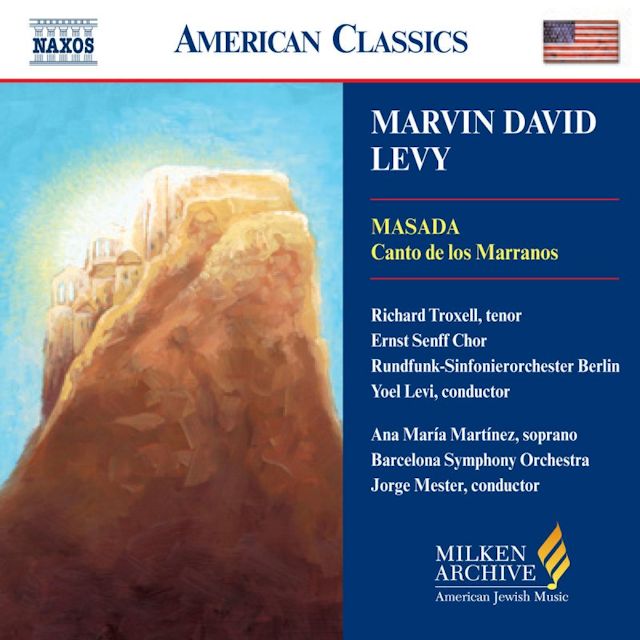

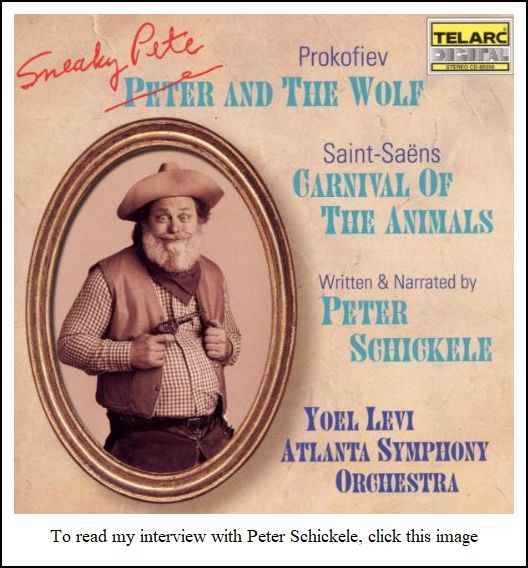

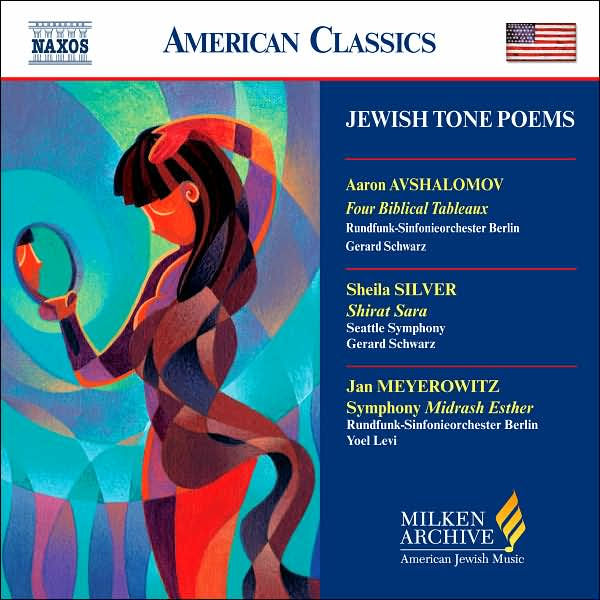

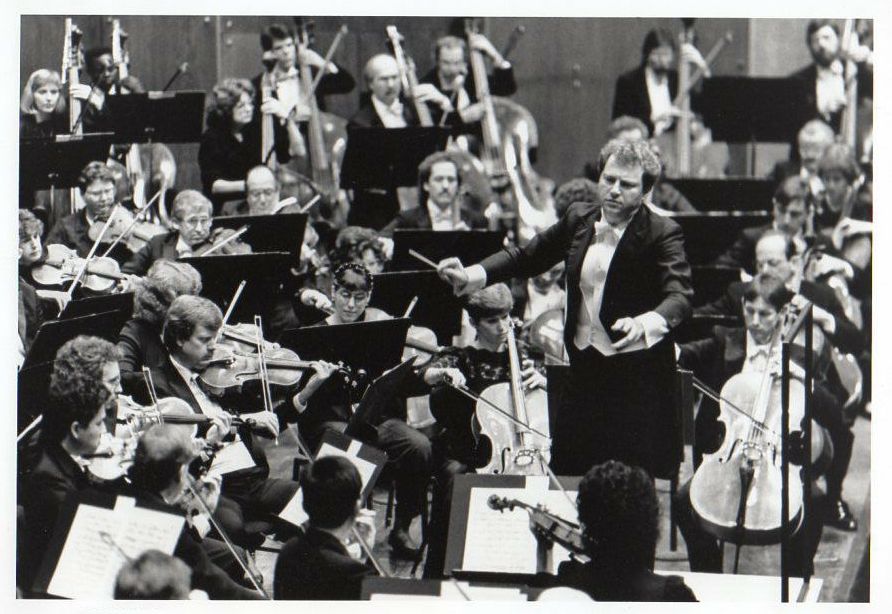

| Yoel Levi is one of the world’s leading conductors,

known for his vast repertoire, masterly interpretations and electrifying

performances. He is Chief Conductor of the KBS Symphony Orchestra

in Seoul, a position he has held since 2014. The fourth Seoul Arts

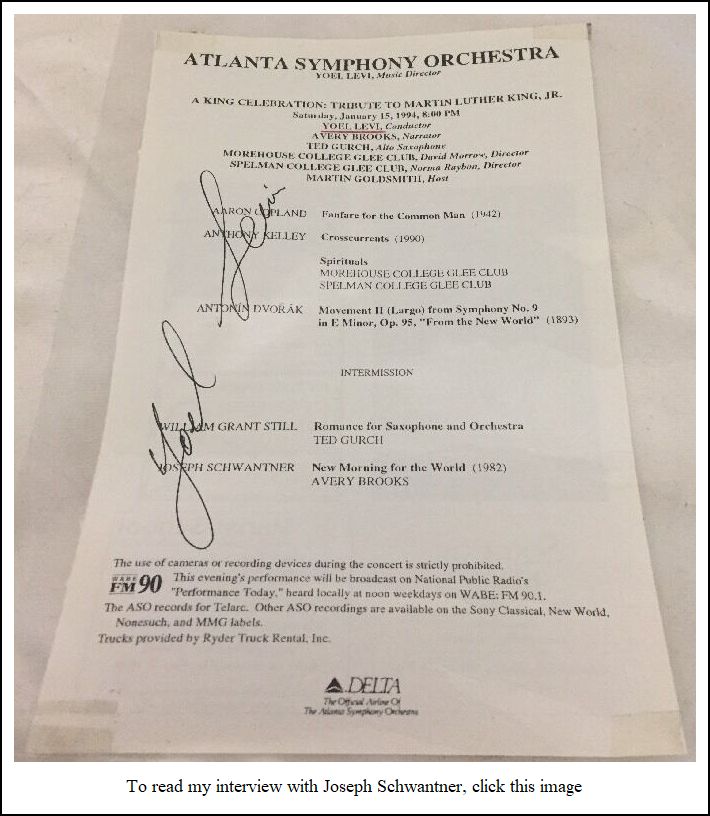

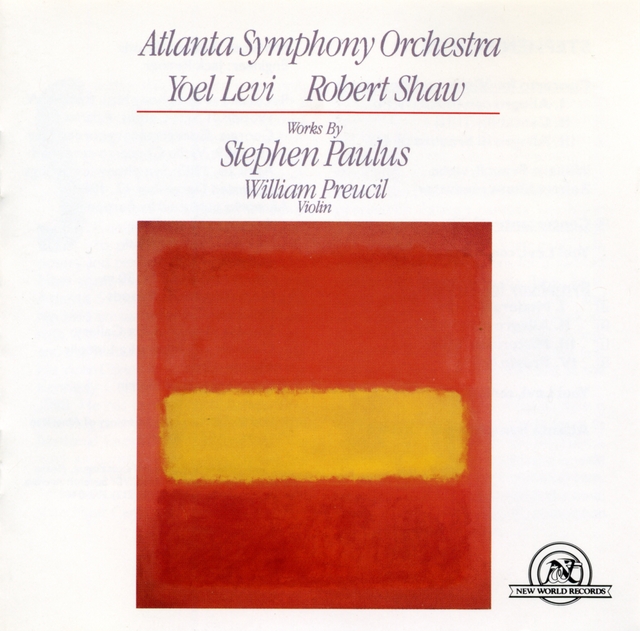

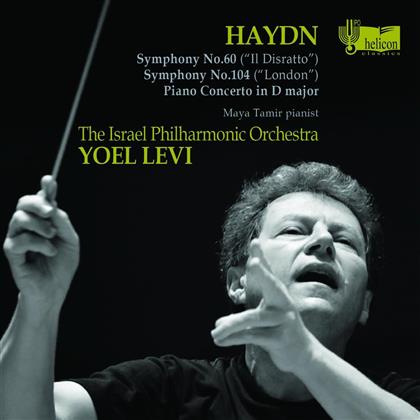

Center Awards bestowed Mr. Levi and the KBS Symphony Grand Prize in 2017. Having conducted some of the most prestigious orchestras throughout the world and appearing with esteemed soloists, Levi has led orchestras in North America that include the Cleveland and Philadelphia Orchestras, the Boston, Chicago and San Francisco Symphonies, and the New York Philharmonic, to name a very few. In Europe he has led orchestras in cities that include London, Paris, Berlin, Prague, Budapest, Rome, Frankfurt and Munich and in the Far East, in addition to South Korea, he has conducted in Japan and China. Also, Mr. Levi has conducted some of the world’s leading opera companies, including the Lyric Opera of Chicago, in addition to leading productions in Florence, Genoa, Prague, Brussels, and throughout France. Levi’s extensive discography--on several labels featuring many composers-- numbers more than forty. This includes more than thirty with the Atlanta Symphony on the Telarc label. He was Music Director of the Atlanta Symphony from 1988 to 2000. Other posts have included Principal Conductor of the Brussels Philharmonic from 2001-2007 and Principal Conductor of the Orchestre National d’Ile de France from 2005 to 2012. He was the first Israeli to serve as Principal Guest Conductor of the Israel Philharmonic. Levi won first prize at the International Conductors Competition in Besançon in 1978 before spending six years as the assistant of Lorin Maazel and resident conductor at the Cleveland Orchestra. He then assumed the post of Music Director at Atlanta. Other highlights of his career include a recent successful European tour with the KBS Symphony. Similarly, during his tenure at the helm of France’s Orchestre National d'Ile he conducted that orchestra in regular concerts in Paris, and on tours to London, Spain and Eastern Europe. With the Israel Philharmonic, he conducted tours of the United States including their most recent tour in 2019. Also, he has conducted the IPO on tour to Mexico and led them in a special concert celebrating the 60th Anniversary of State of Israel. Other recent tours include an extensive tour of New Zealand with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, and highly acclaimed concerts in Spain with the Orchestre de Paris. Frequently Levi is invited to conduct at special events such as the Nobel Prize Ceremony with the Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra. In 1997, Levi was awarded an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts Degree by Oglethorpe University in Atlanta. In June, 2001 he was awarded “Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres” by the French Government. Born in Romania August 15, 1950, Levi was raised in Israel where he studied at the Tel Aviv Academy of Music. Receiving a Master of Arts degree with distinction, he also studied under Mendi Rodan at The Jerusalem Academy of Music. Subsequently Levi studied with Franco Ferrara in Siena and Rome, and with Kirill Kondrashin in the Netherlands, and at London’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama. == Throughout this webpage, names which are

links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

Bruce Duffie: You are in the middle of the

run of Carmen. Tonight will be the eighth

of thirteen performances. Is it your responsibility to keep each

performance fresh and bubbly?

Bruce Duffie: You are in the middle of the

run of Carmen. Tonight will be the eighth

of thirteen performances. Is it your responsibility to keep each

performance fresh and bubbly? BD: Is there ever a night that

you get it just right?

BD: Is there ever a night that

you get it just right? BD: When you work with living composers,

does the insight that you gain from their ideas and their methods help

you when you work with Beethoven and Mahler and Mozart?

BD: When you work with living composers,

does the insight that you gain from their ideas and their methods help

you when you work with Beethoven and Mahler and Mozart?

BD: Then you’re assuming that any

piece you conduct will be a great work when you conduct it?

BD: Then you’re assuming that any

piece you conduct will be a great work when you conduct it? BD: I assume that most of the music

that you conduct is secular rather than sacred, but do you try to find

a spiritual quality in each piece of music?

BD: I assume that most of the music

that you conduct is secular rather than sacred, but do you try to find

a spiritual quality in each piece of music? Levi: They’re different by the nature

of the culture, from the Far East to somewhere within Europe. You

have so many different nations within Europe, so everyone has different

mentalities. Some are more conservative, some are more open and more

enthusiastic. Some could be very brutal, which is fine. That’s

wonderful. For me, it doesn’t make any difference. It should

not change from your musicmaking. You still have to do the same way

of great musicmaking any place you go.

Levi: They’re different by the nature

of the culture, from the Far East to somewhere within Europe. You

have so many different nations within Europe, so everyone has different

mentalities. Some are more conservative, some are more open and more

enthusiastic. Some could be very brutal, which is fine. That’s

wonderful. For me, it doesn’t make any difference. It should

not change from your musicmaking. You still have to do the same way

of great musicmaking any place you go.

© 2000 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at the Opera House in Chicago on March 6, 2000. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following July. This transcription was made in 2019, and posted on this website in 2020. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.