| John Mauceri, world-renowned

conductor, educator and writer, has appeared with the world’s greatest

opera companies and symphony orchestras, on the musical stages of

Broadway and Hollywood as well as at the most prestigious hall of

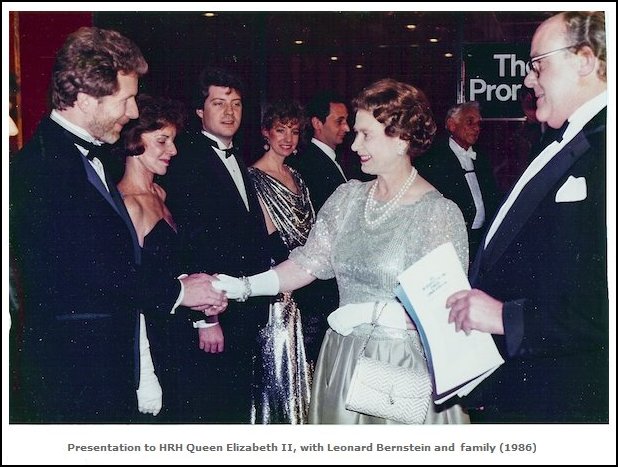

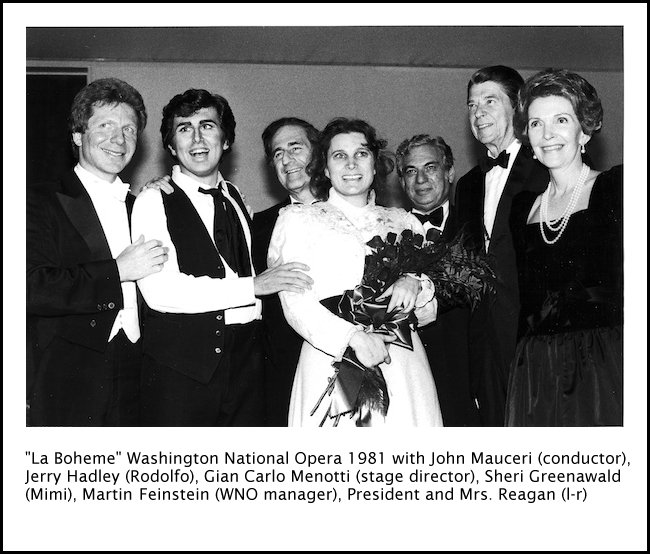

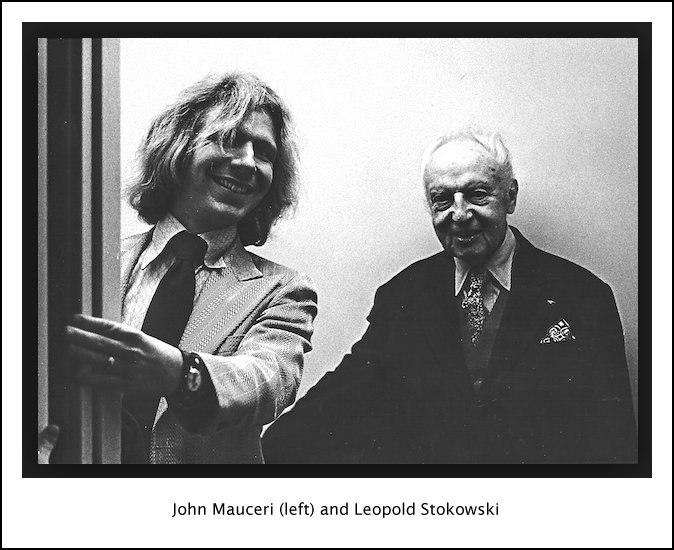

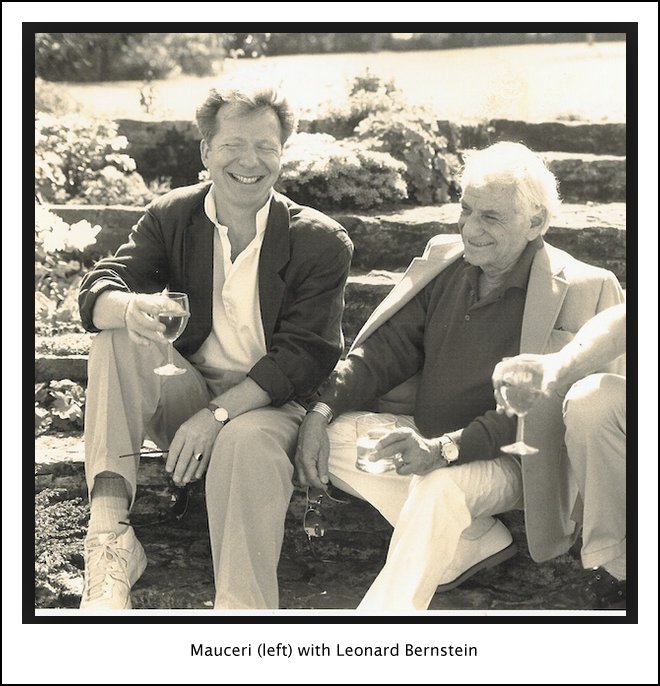

academia. Mr. Mauceri served as music director (direttore stabile) of the Teatro Regio in Turin, Italy for three years after completing seven years (22 productions and three recordings) as music director of Scottish opera, and is the first American ever to have held the post of music director of an opera house in either Great Britain or Italy. He was music director of the Washington Opera (The Kennedy Center) as well as Pittsburgh Opera, and was the first music director of American Symphony Orchestra in Carnegie Hall after its legendary founding director, Leopold Stokowski, with whom he studied. For fifteen years he served on the faculty of his alma mater, Yale University, and returned in 2001 to teach and conduct the official concert celebrating the university’s 300th anniversary. For 18 years, Mr. Mauceri worked closely with Leonard Bernstein and conducted many of the composer’s premieres at Bernstein’s request.  He is the Founding Director of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, which was created for him in 1991 by the Los Angeles Philharmonic Association. Breaking all records at the Bowl, he conducted over 300 concerts at the 18,000-seat amphitheater with a total audience of four million people. One of Los Angeles’ most beloved figures, he has been honored with many awards and commendations, including “John Mauceri Day” in the state of California, receiving a Treasure of Los Angeles Award, and the Young Musicians Foundation Award. For seven years (2006-2013) he served as chancellor of the University of North Carolina’s School of the Arts, America’s first public arts conservatory-university. He has conducted at New York’s Metropolitan Opera, London’s Royal Opera House (Covent Garden), Milan’s Teatro alla Scala, Berlin’s Deutsche Oper, the New York Philharmonic, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Boston Symphony Orchestra, all the major London orchestras, as well as l’Orchestre Nationale de France and the Israel Philharmonic.  On Broadway, he was co-producer of On Your Toes, and served as musical

supervisor for Hal

Prince’s production of Candide,

as well as Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Song

and Dance with Bernadette Peters. He also conducted the

orchestra for the film version of Evita. On Broadway, he was co-producer of On Your Toes, and served as musical

supervisor for Hal

Prince’s production of Candide,

as well as Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Song

and Dance with Bernadette Peters. He also conducted the

orchestra for the film version of Evita.

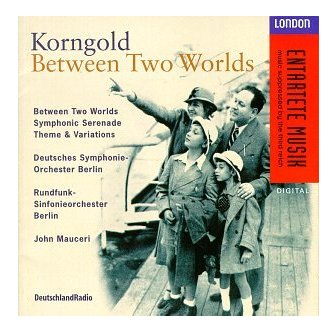

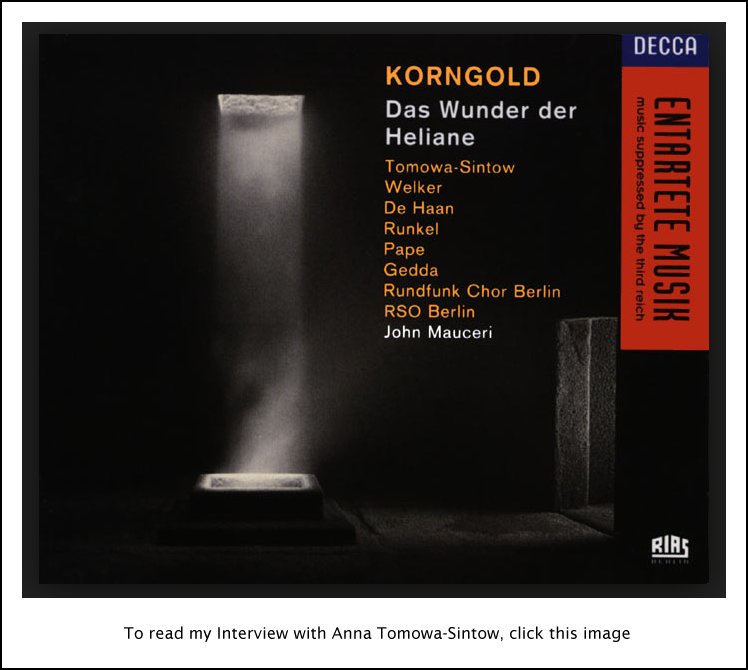

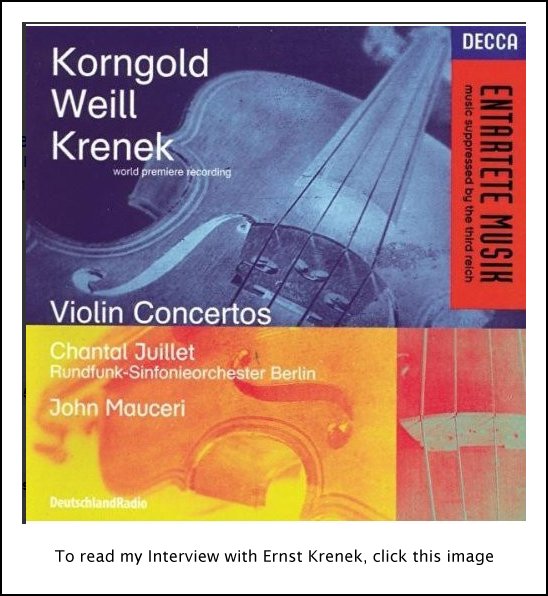

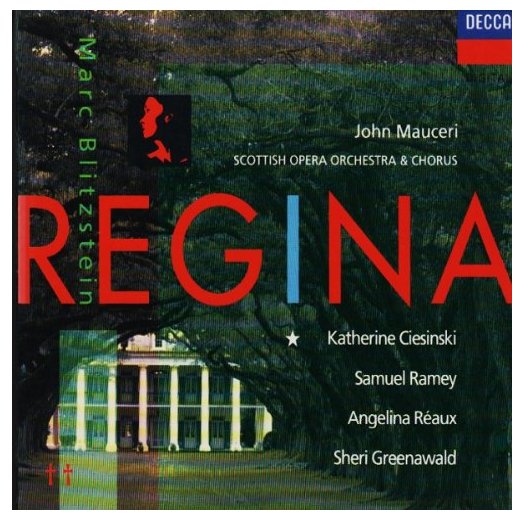

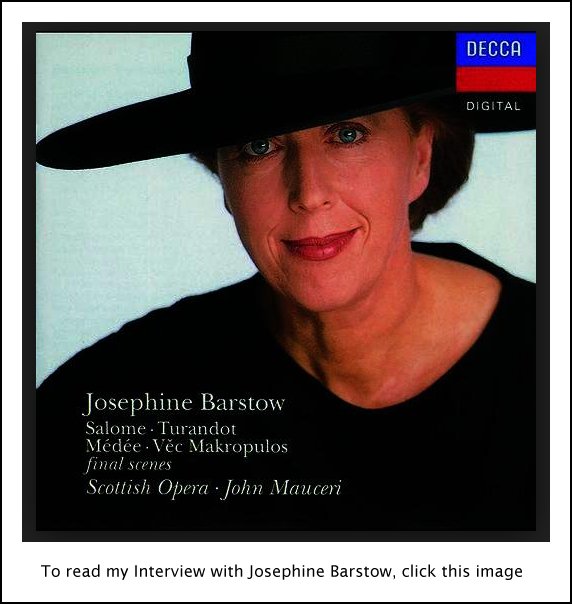

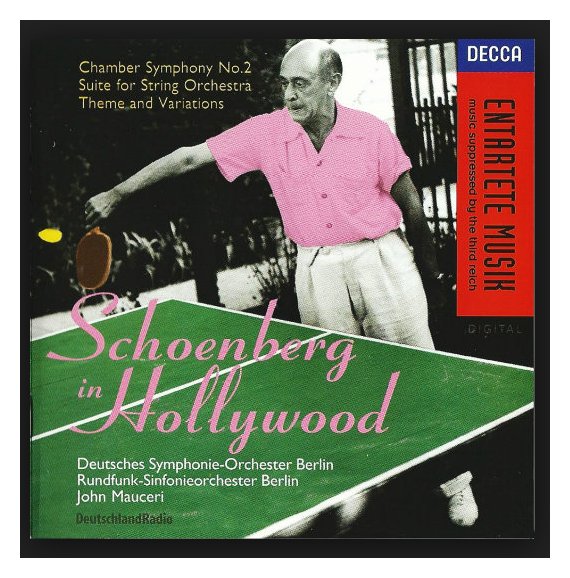

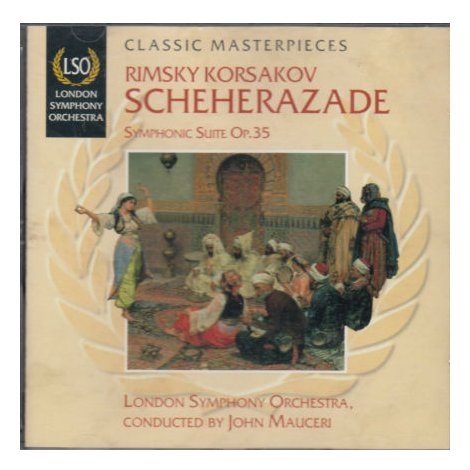

Deeply committed to preserving two American art forms, the Broadway musical and Hollywood film scores, he has edited and performed a vast catalogue of restorations and first performances, including a full restoration of the original 1943 production of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Oklahoma!, performing editions of Gershwin’s Porgy & Bess, Girl Crazy, and Strike up the Band, Bernstein’s Candide and A Quiet Place, and film scores by Miklós Rózsa, Franz Waxman, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Max Steiner, Elmer Bernstein, Jerry Goldsmith, Danny Elfman and Howard Shore. As one of two conductors in Decca Records’ award-winning series “Entartete Musik,” Mauceri made a number of historic first recordings of music banned by the Nazis. The intersection of the “degenerate composers” of Europe and the refugee composers of Hollywood is the subject of much of his research and his writings. In addition, Mr. Mauceri has conducted significant premieres of works by Verdi, Debussy, Hindemith, Ives, Stockhausen, and Weill. In articles, speeches, radio and television appearances, John Mauceri has taken his passion for music and the importance of the arts to audiences throughout the world. These include Harvard University, Yale University, the Smithsonian Institution, the NEA, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Gramophone Magazine, NPR, BBC, PBS, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and the Huffington Post where he regularly writes a blog. Mr. Mauceri is one of the world’s most accomplished recording artists, having released over 75 audio CDs and is the recipient of Grammy, Tony, Olivier, Drama Desk, Edison Klassiek, 3 Emmy Awards, 2 Diapasons d’Or, Cannes Classique, ECHO Klassik, Billboard, and four Deutsche Schallplatten awards. In 1999, Mr. Mauceri was chosen as a “Standard-bearer of the Twentieth Century” for WQXR, America’s most-listened-to classical radio station. According to WQXR, “These are a select number of musical artists who have already established themselves as forces to be reckoned with, and who will be the Standard Bearers of the 21st Century’s music scene.” The recipients were chosen for “their visionary talent and technical virtuosity.” In addition, CNN and CNN International chose Mr. Mauceri as a “Voice of the Millennium”. -- Throughout this webpage,

names which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on this

website. BD

|

John Mauceri: I

like being a wandering minstrel. Not to give you a stupid

answer, but the answer is really ‘sometimes’.

Sometimes I am happy to be

in beautiful parts of the world and being in new places, and other

times it’s a real pain in the neck. It just depends on your

mood. It just happens to be the way the job works. So I

suppose when all is said and done I do prefer traveling, but I also

like going back to places I’ve been to before because you

know some of the people and you know the lay of the land, and you feel

a little more comfortable. The combination of traveling

and having jet lag, and speaking a foreign language, and being in front

of a new orchestra, and trying to figure out your way to the theater

and all of that combines to make the job even more difficult. As

you can imagine, being a conductor is the hardest thing you can

do. So, yes, it’s okay that we have to travel and there

are some times when you’re really grateful to be in some wonderful

place.

John Mauceri: I

like being a wandering minstrel. Not to give you a stupid

answer, but the answer is really ‘sometimes’.

Sometimes I am happy to be

in beautiful parts of the world and being in new places, and other

times it’s a real pain in the neck. It just depends on your

mood. It just happens to be the way the job works. So I

suppose when all is said and done I do prefer traveling, but I also

like going back to places I’ve been to before because you

know some of the people and you know the lay of the land, and you feel

a little more comfortable. The combination of traveling

and having jet lag, and speaking a foreign language, and being in front

of a new orchestra, and trying to figure out your way to the theater

and all of that combines to make the job even more difficult. As

you can imagine, being a conductor is the hardest thing you can

do. So, yes, it’s okay that we have to travel and there

are some times when you’re really grateful to be in some wonderful

place.

JM: Except scream,

yes. That’s what he had to do, but

that was his nature. You see film

of Richard Strauss or Furtwängler conducting, and they didn’t

actually have to physically do what we do now because they had twenty

times more rehearsal than we have.

JM: Except scream,

yes. That’s what he had to do, but

that was his nature. You see film

of Richard Strauss or Furtwängler conducting, and they didn’t

actually have to physically do what we do now because they had twenty

times more rehearsal than we have. JM: Half the time it’s

decided for you. It’s a romantic idea that conductors are

totally under the spell of that period of the 20s and 30s where there

are maestros. I think the ‘maestro’ is sort of a dead

concept. When we get

into the next century it will become less and less, rather than

seemingly more and more silly. That tyrant guy who has thrown

batons at people and walked off the stage

because somebody played an F# instead of an F is part of a

period of twentieth century history which brought up such ‘delightful’

people

as Adolf Hitler and Mussolini, and it’s part of our

thing. Probably someone will write a book about the

response of the Industrial Revolution and the destruction of

monarchies, and the rise of political leaders who then, in their own

right, become more autocratic than the kings and queens they

deposed. While Toscanini was democrat from the point of view of

his

politics, he was a total authoritarian. That doesn’t work

anymore and it is not necessary. In fact, it’s the opposite of

what’s necessary right now. Only certain music needs a

conductor. It’s a certain period of time when composers were

really writing with conductors in mind, and that happens

especially in opera somewhere in the 1860s. When you do

Rigoletto and you have a

conductor standing in front of the orchestra

grinding his teeth at them and forcing them into speeds that are

faster or slower than they’re written, that’s not what

Verdi had in mind in the 1850s. There was no guy there.

That person who was there had his back to the orchestra, and the

orchestra was sort of facing the stage, and they had to rehearse it

with the singers and the composer present. Verdi left very

specific instructions so that after he

died it could be done the way he intended, including metronome

markings.

JM: Half the time it’s

decided for you. It’s a romantic idea that conductors are

totally under the spell of that period of the 20s and 30s where there

are maestros. I think the ‘maestro’ is sort of a dead

concept. When we get

into the next century it will become less and less, rather than

seemingly more and more silly. That tyrant guy who has thrown

batons at people and walked off the stage

because somebody played an F# instead of an F is part of a

period of twentieth century history which brought up such ‘delightful’

people

as Adolf Hitler and Mussolini, and it’s part of our

thing. Probably someone will write a book about the

response of the Industrial Revolution and the destruction of

monarchies, and the rise of political leaders who then, in their own

right, become more autocratic than the kings and queens they

deposed. While Toscanini was democrat from the point of view of

his

politics, he was a total authoritarian. That doesn’t work

anymore and it is not necessary. In fact, it’s the opposite of

what’s necessary right now. Only certain music needs a

conductor. It’s a certain period of time when composers were

really writing with conductors in mind, and that happens

especially in opera somewhere in the 1860s. When you do

Rigoletto and you have a

conductor standing in front of the orchestra

grinding his teeth at them and forcing them into speeds that are

faster or slower than they’re written, that’s not what

Verdi had in mind in the 1850s. There was no guy there.

That person who was there had his back to the orchestra, and the

orchestra was sort of facing the stage, and they had to rehearse it

with the singers and the composer present. Verdi left very

specific instructions so that after he

died it could be done the way he intended, including metronome

markings. BD: You have no

choice about the key, but the speed is very different.

BD: You have no

choice about the key, but the speed is very different. JM: Absolutely, which

is what Wagner invented at his theater in Bayreuth. It solved

certain problems he had vis-à-vis the size of his orchestra and

balance. He wanted to see the stage and not be encumbered

with harps and tops of basses and things like that, so he put the pit

down there, made it deeper and covered it. It

created tremendous problems, and morale problems for the orchestra

which sits under the stage. They don’t

know what the hell’s going on upon the stage. They feel like

animals. No orchestra likes playing in a pit.

JM: Absolutely, which

is what Wagner invented at his theater in Bayreuth. It solved

certain problems he had vis-à-vis the size of his orchestra and

balance. He wanted to see the stage and not be encumbered

with harps and tops of basses and things like that, so he put the pit

down there, made it deeper and covered it. It

created tremendous problems, and morale problems for the orchestra

which sits under the stage. They don’t

know what the hell’s going on upon the stage. They feel like

animals. No orchestra likes playing in a pit. BD:

Our curtain can open and close that way. Why didn’t

you demand that?

BD:

Our curtain can open and close that way. Why didn’t

you demand that? JM: That’s where the

heart comes in, but also the

technique. I knew Stokowski a little bit near the end of his

life, and for some

reason he reminisced a lot with me, which surprised his secretary a

great deal. He told me lots of fantastic stories, which

have never been published because he never wrote his memoirs. He

was always talking about the

future. He was at the rehearsals for the world premiere of the

Mahler Eight in September of

1910. He would show up with an empty violin case as if he

were in the orchestra, and go up into the balcony because all the

rehearsals were closed. The part of this that’s relevant to

this conversation is that he said the orchestra hated Mahler because he

kept changing the orchestration. For instance, it was because in

that hall he

needed to hear that line so he added three clarinets. That’s why

there

are so many versions of Mahler’s symphonies. It’s not that he was

rethinking for old time sake, he was rethinking it for the Vienna Opera

House, or he was rethinking it for Carnegie Hall, or he was

thinking about it for the Concertgebouw, or wherever he was conducting

because he rebalanced his symphonies — and

everyone else’s — for the hall.

JM: That’s where the

heart comes in, but also the

technique. I knew Stokowski a little bit near the end of his

life, and for some

reason he reminisced a lot with me, which surprised his secretary a

great deal. He told me lots of fantastic stories, which

have never been published because he never wrote his memoirs. He

was always talking about the

future. He was at the rehearsals for the world premiere of the

Mahler Eight in September of

1910. He would show up with an empty violin case as if he

were in the orchestra, and go up into the balcony because all the

rehearsals were closed. The part of this that’s relevant to

this conversation is that he said the orchestra hated Mahler because he

kept changing the orchestration. For instance, it was because in

that hall he

needed to hear that line so he added three clarinets. That’s why

there

are so many versions of Mahler’s symphonies. It’s not that he was

rethinking for old time sake, he was rethinking it for the Vienna Opera

House, or he was rethinking it for Carnegie Hall, or he was

thinking about it for the Concertgebouw, or wherever he was conducting

because he rebalanced his symphonies — and

everyone else’s — for the hall. BD: Are you a big fan

and advocate of

contemporary music?

BD: Are you a big fan

and advocate of

contemporary music? BD: Not only

onstage, but also in movies and even animated cartoons!

BD: Not only

onstage, but also in movies and even animated cartoons!| In 1989, two years after this

interview with John Mauceri, Lyric Opera of Chicago launched its Toward the 21st Century artistic

initiative – the most important artistic initiative the company had

undertaken to date, and one with far-reaching impact on American opera

in North America as well as in the international opera community.

Throughout the 1990s Lyric produced one 20th-century European and one

American opera each season as part of the regular subscription series.

Within this initiative Lyric commissioned three new works: William

Bolcom’s McTeague (1992-93),

Anthony Davis’s Amistad

(1997-98), and Bolcom’s A View from

the Bridge (1999-00). Other operas by Americans included The Voyage of Edgar Allan Poe by

Dominick Argento (revised for this occasion in 1990-91), Antony and Cleopatra by Barber

(1991-92, and telecast by PBS), Susannah

by Carlisle Floyd (1993-94, and 2003-04), Candide by Leonard Bernstein

(1994-95), The Ghosts of Versailles

by John Corigliano

(1995-96), The Consul by Gian

Carlo Menotti (1996-97), Mourning

Becomes Elektra by Marvin David Levy (1998-99), and The Great Gatsby by John Harbison

(2000-01). Then in 2014-15 Lyric Unlimited presented three world

premieres: the mariachi opera, El

Pasado Nunca Se Termina by José “Pape” Martínez

and Leonard Foglia; The Property

by Wlad Marhulets; and Second Nature

by Matthew Aucoin. Prior to these, the Lyric Opera Center for American Artists had engaged its first Composer-in-Residence (William Neil) whose Guilt of Lilian Sloan (libretto by Frank Galati) was produced in 1985-86, and its second Composer-in-Residence (Lee Goldstein) whose The Fan (libretto by Charles Kondek) was produced in 1988-89. Subsequent productions by the Lyric Center included The Song of Majnun by Bright Sheng (libretto by Andrew Porter) in 1991-92, Orpheus Descending by Bruce Saylor (libretto by J.D. McClatchy) in 1993-94, Between Two Worlds (The Dybbuk) by Shulamit Ran (libretto by Charles Kondek) in 1996-97, and Lovers and Friends (Chautauqua Variations by composer/librettist Michael John LaChiusa in 2000-01. It should also be noted that early in its history, Lyric presented two operas by the American composer Vittorio Giannini - The Taming of the Shrew in 1954, Lyric's first season, and the world premiere of The Harvest in 1961. |

BD: Now he’s gone off

the whole project?

BD: Now he’s gone off

the whole project? JM: I strive to be

totally comfortable inside myself

with what I’m doing. As I live, I know that all these

experiences in my life somehow inform my art, whatever that is, and

also sensitize me to what the music is saying. So I do think I’m

getting better, but even that is subjective. The other day I

listened to a

recording of me conducting the Sibelius Second Symphony from something

like thirteen or fourteen years ago. I

loved it, and I have no physical or emotional linkage with it that

says that’s how I do that! There were lots of new things, and

things that I’d forgotten

because I haven’t conducted it since those

performances. My memory of the years before that have to do with

standard performances of the work. So when I studied it, I did

whatever it was that it came out to

be. When it said molto

largamente, I conducted molto

largamente. I didn’t cheat those bars, which a lot of

people do. They don’t hold the chord, for it’s a long time.

He

wrote molto largamente, and

it stays there for a very long

time. So I did all that, and I listened to it the other day, and

I must confess that I loved it. I didn’t like

the first movement. It was too fast and not graceful

enough, but the rest of it I really did love. But if I conducted

it tomorrow, I don’t

know if I can imitate myself from fifteen years ago!

JM: I strive to be

totally comfortable inside myself

with what I’m doing. As I live, I know that all these

experiences in my life somehow inform my art, whatever that is, and

also sensitize me to what the music is saying. So I do think I’m

getting better, but even that is subjective. The other day I

listened to a

recording of me conducting the Sibelius Second Symphony from something

like thirteen or fourteen years ago. I

loved it, and I have no physical or emotional linkage with it that

says that’s how I do that! There were lots of new things, and

things that I’d forgotten

because I haven’t conducted it since those

performances. My memory of the years before that have to do with

standard performances of the work. So when I studied it, I did

whatever it was that it came out to

be. When it said molto

largamente, I conducted molto

largamente. I didn’t cheat those bars, which a lot of

people do. They don’t hold the chord, for it’s a long time.

He

wrote molto largamente, and

it stays there for a very long

time. So I did all that, and I listened to it the other day, and

I must confess that I loved it. I didn’t like

the first movement. It was too fast and not graceful

enough, but the rest of it I really did love. But if I conducted

it tomorrow, I don’t

know if I can imitate myself from fifteen years ago!

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 30, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1990, and again in 199 and 2000, and on WNUR in 2003 and 2013. This transcription was made in 2016, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.