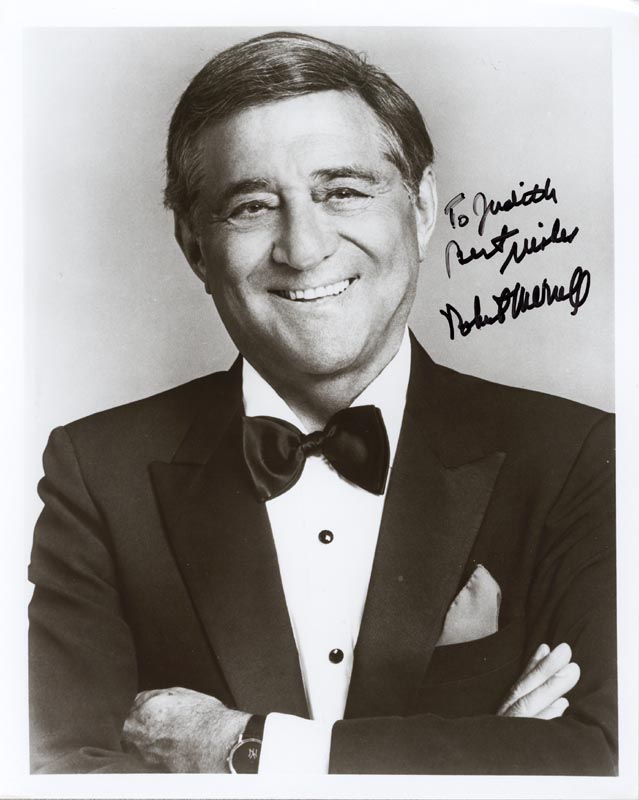

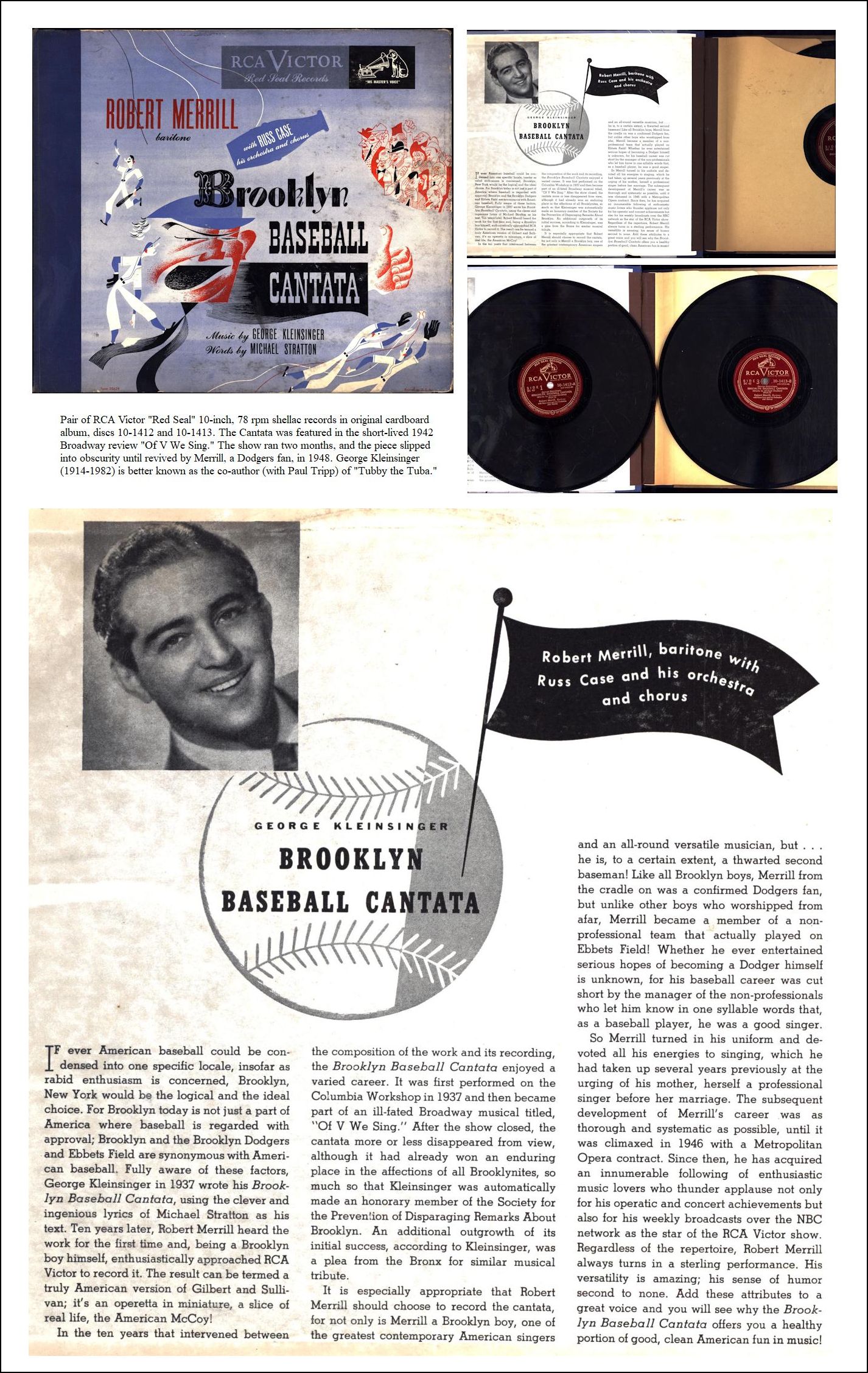

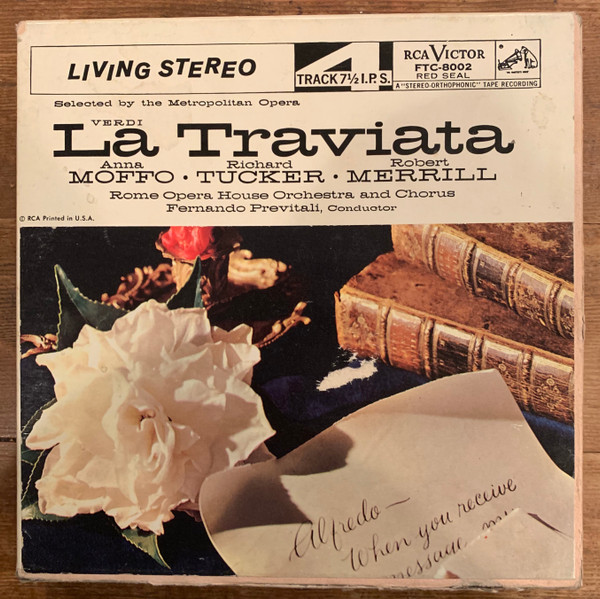

Robert Merrill(b. 4 June 1917 in New York City; d. 23 October 2004 in New Rochelle, New York), baritone who enjoyed a long career with the Metropolitan Opera Company. Merrill was born Moishe (Morris) Miller, one of two sons born to Abraham Millstein, a sewing machine operator, and Lotza (Lillian) Balaban Millstein, a singer. The couple took the name Miller after emigrating from Poland to the United States. Merrill’s mother did not have the opportunity to study voice or sing professionally in Poland and determined that her son would become a singer, but all Merrill wanted to do was play baseball. While attending New Utrecht High School, he played baseball for the school team and also played semiprofessional ball, earning $10 a game. Merrill tried out for the Brooklyn Dodgers but was rejected and turned to singing. Merrill’s mother was his first teacher. She persuaded him to sing for the radio station WFOX, where he was employed imitating the crooning of Bing Crosby three times a week, unpaid and using the name Merrill Miller to “keep my musical activities secret from the gang.” When Merrill was sixteen, his voice changed to a “booming baritone,” and his mother employed the professional voice teacher Samuel Margolis, who was Merrill’s teacher throughout his career. Merrill dropped out of high school and began working for his uncle, sweeping floors and making deliveries. One afternoon, while pushing a handcart of dresses in the garment district of New York City, Merrill overheard a rehearsal at the Metropolitan Opera House and became determined to be an opera star. To support his vocal studies with Margolis, Merrill worked a number of menial jobs and sang wherever he could get a paycheck. He was particularly successful on the “borscht circuit,” becoming a favorite at Grossinger’s resort in the Catskill Mountains. Merrill tried out for the Major Bowes Original Amateur Hour in 1936 and won first prize, singing the classic baritone aria “Largo al factotum,” from Rossini’s The Barber of Seville. This opportunity led to other engagements singing in theaters, clubs, and synagogues. Merrill’s dream was to sing opera, and in 1941 he auditioned for the Metropolitan Opera Auditions of the Air. Singing “Largo al factotum” in the manner that had wowed audiences at Grossinger’s, Merrill failed, but he continued singing where he could. The exposure resulted in his being offered the opportunity to sing “The Star-Spangled Banner” for Movietone News. Merrill’s recording of the national anthem was played at every theater in the country and earned him the sobriquet “the Star-Spangled Baritone.” He attracted the attention of the music agent Moe Grant, who found Merrill work at Radio City Music Hall and on the radio show Serenade to America. In 1944, when Merrill was rehearsing for a benefit, the conductor Mark Warrow renamed him Robert Merrill because the name “had star quality.” Merrill made his opera debut in 1944, singing Amonasro in Verdi’s Aida in Newark, New Jersey. In November 1944 Merrill again auditioned for the Metropolitan Opera, singing a disciplined “Largo al factotum.” In the finals, Merrill sang Iago’s “Credo” from Otello and won a contract, which he signed in June 1945. On 15 December 1945 Merrill made his Metropolitan Opera debut in

the lead role of Germont in Verdi’s La Traviata. Merrill sang

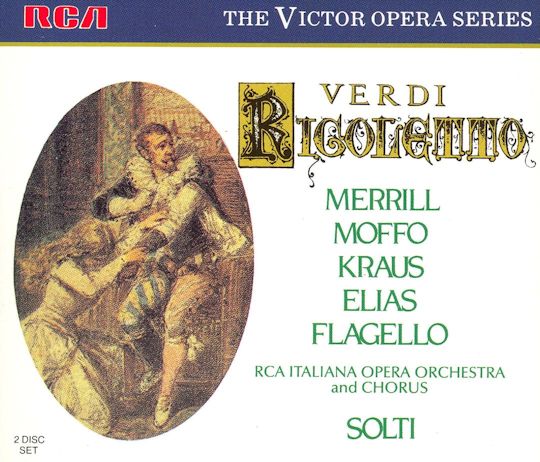

at the Met for thirty-one consecutive seasons. He became the principal

Verdi baritone, singing major roles, including Rodrigo in Don Carlos

at the opening night gala to celebrate the beginning of the era of Rudolf

Bing, the general manager of the Met from 1950 to 1972. Merrill sang

132 performances of Germont. Roles in operas by composers other than

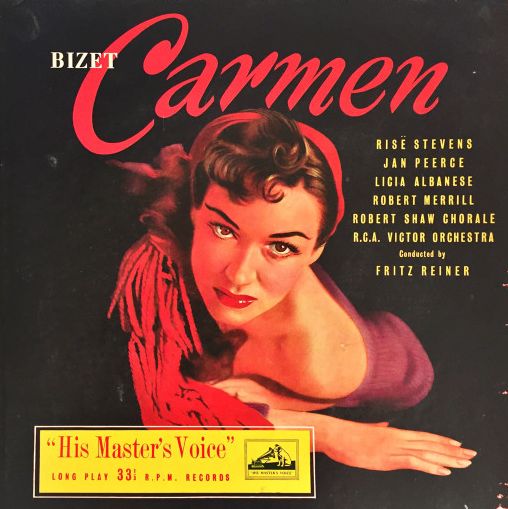

Verdi included Escamillo in Bizet’s Carmen, Figaro in The

Barber of Seville, and Scarpia in Puccini’s Tosca. In 1946 the

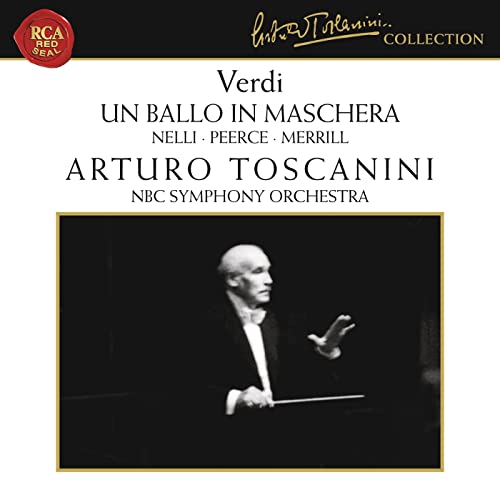

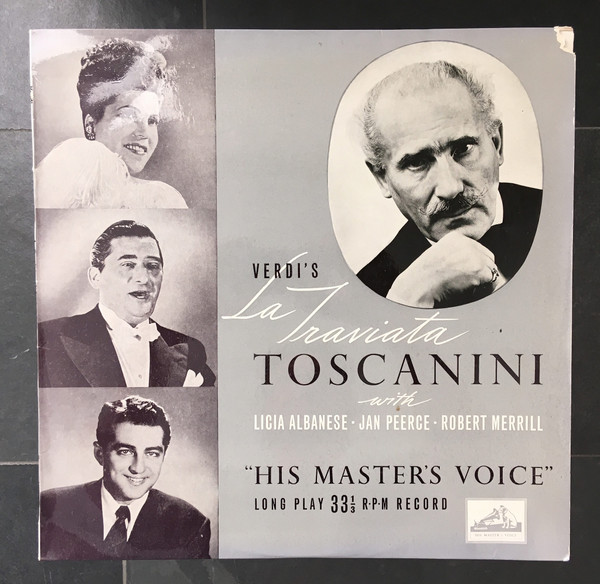

conductor Arturo Toscanini invited Merrill to audition for the NBC radio

broadcast of La Traviata. Merrill sang Germont in the two-part

broadcast, and Toscanini engaged him again in 1954 to sing Renato in Verdi’s

Un Ballo in Maschera.

Merrill was the only singer chosen to appear at a service held by both houses of Congress in July 1946 in memory of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Merrill sang the president’s favorite “Eternal Father, Strong to Save” and “The Lord’s Prayer.” Merrill’s career at the Metropolitan Opera was interrupted in 1951 when he played the part of Bill Merridew in the film Aaron Slick from Punkin Crick (1952), later described by Merrill “the biggest turkey in Hollywood history.” When filming conflicted with his opera obligations and Merrill told Bing that he could not travel with the company for the spring tour, Bing fired him. It took a public apology in a letter published in the New York Times for Bing to agree to reinstate the baritone. Merrill married the Metropolitan Opera soprano Roberta Peters on 30 March 1952; they divorced on 26 June 1952. On 30 May 1954 Merrill married the pianist Marion Machno, and the couple had two children. Although his singing career centered on the Metropolitan Opera,

Merrill also sang at major opera houses in Rome, London, and Venice.

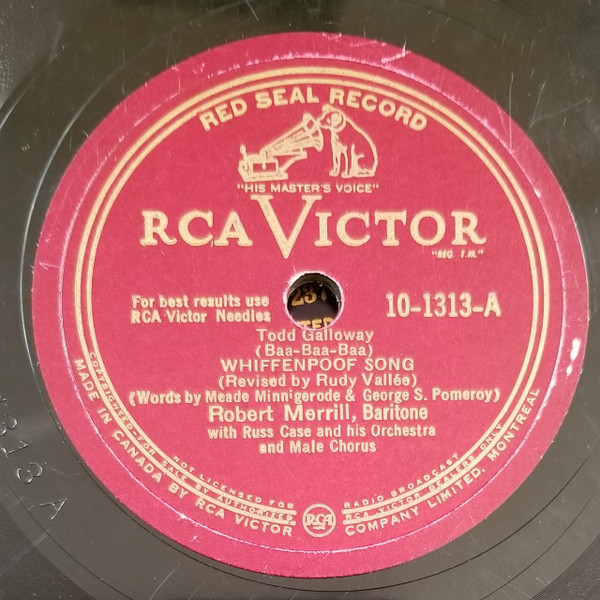

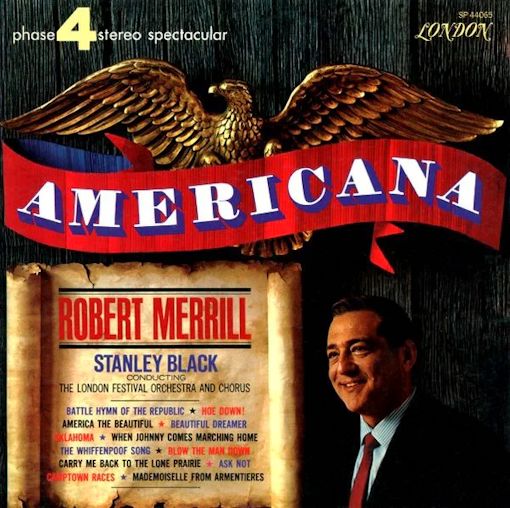

He continued to sing on the radio as the featured soloist on The

RCA Victor Show, on television, and in concerts. He had a successful

recording career in both classical and popular music. In 1947 Merrill’s

recording of “The Whiffenpoof Song” was number one on the Hit Parade.

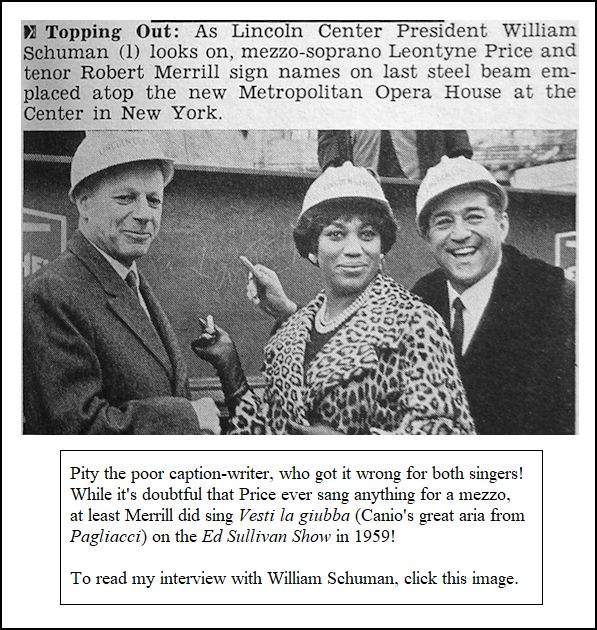

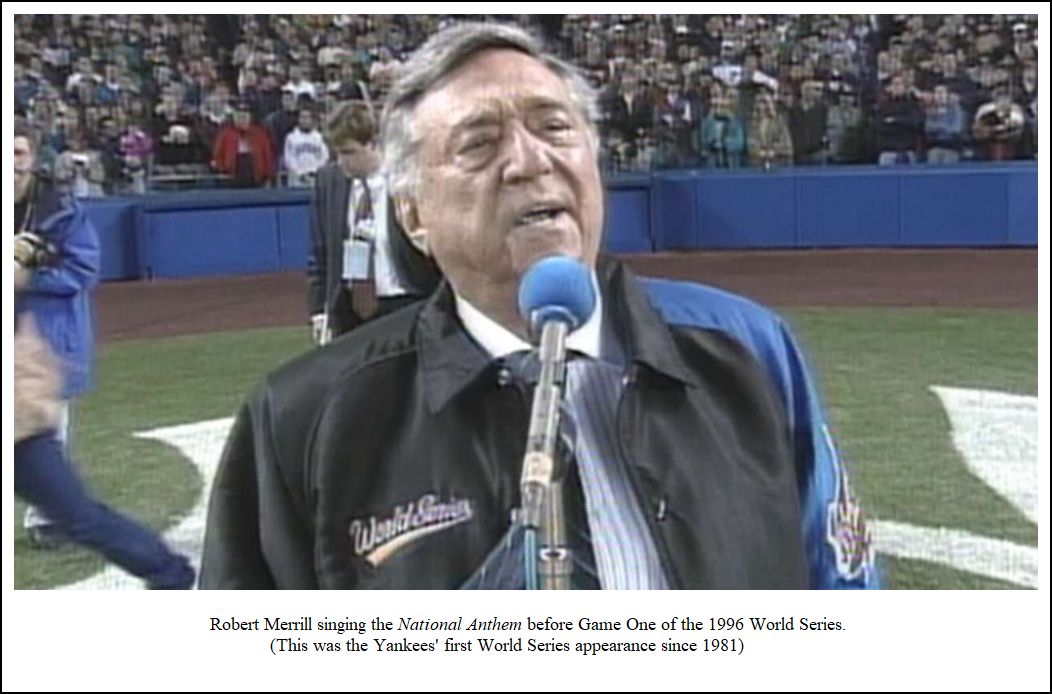

Merrill became a popular guest on television, not only singing arias for Ed Sullivan’s Toast of the Town but also telling stories on The Tonight Show, first with Jack Paar and then with Johnny Carson. Merrill’s anecdotes helped make opera more accessible to a public who had preconceived ideas about opera stars being boring and stiff. Merrill retired from the Met in 1976 after 787 performances, having sung twenty-one roles. He took the stage again in 1983 for the centennial gala, singing Sigmund Romberg’s “Will You Remember” with his former costar Anna Moffo. In addition to concert appearances and touring in summer stock productions, Merrill wrote two autobiographies: Once More from the Beginning with Sanford Dody (1965) and Between Acts: An Irreverent Look at Opera and Other Madness with Robert Saffron (1976). Merrill also wrote with Fred Jarvis the novel The Divas (1978). Merrill’s passion for baseball never abated. He was an ardent New York Yankees fan, and beginning in 1969 he sang the national anthem wearing his Yankees jersey, number 1½, to inaugurate each season. Merrill’s recording of the national anthem was played before every home game. In 1986 Merrill became the first person to sing the national anthem and then throw out the first pitch of the home opener at Yankee Stadium. Merrill died of natural causes in New Rochelle on 23 October 2004 while he was watching the World Series. He is buried in Sharon Gardens Cemetery, Valhalla, New York. Trained entirely in the United States, Merrill was the baritone of choice for years at the Metropolitan Opera. His exposure to the public ranged beyond the stage to radio, television, and even Yankee Stadium. A major part of his work was creating a visibility for opera and its stars. “Rise of Merrill,” Newsweek (3 July 1950), covers Merrill’s early years; Milton Bracker, “Brooklyn Greets Own Opera Star,” New York Times (3 Apr. 1960), emphasizes Merrill’s baseball prowess; Ira Siff, “Most Valuable Player,” Opera News (Aug. 2003), is a detailed discussion of Merrill’s career. Obituaries are in the New York Times (26 Oct. 2004) and Opera News (Jan. 2005). Marcia B. Dinneen |

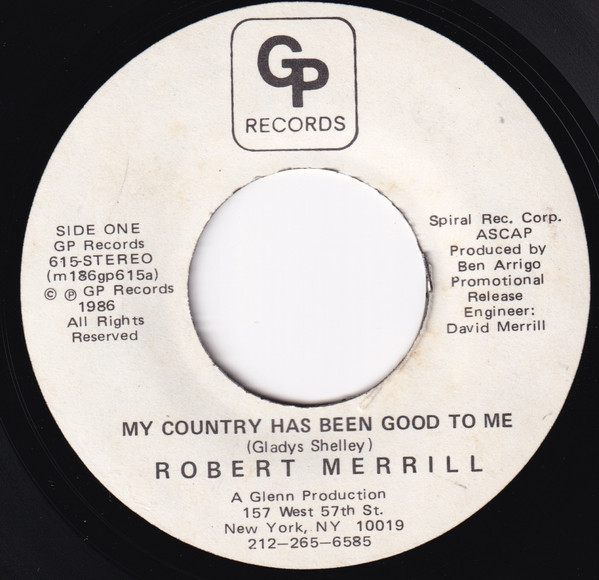

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on February 23, 1986. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following week, and again in 1987 and 1997. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.