|

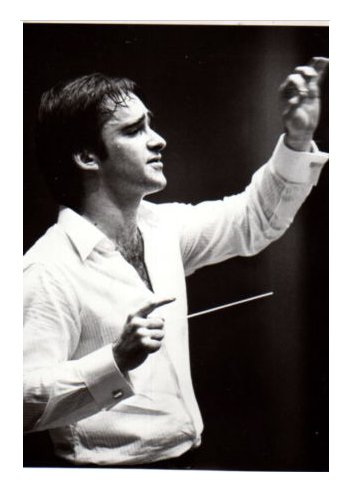

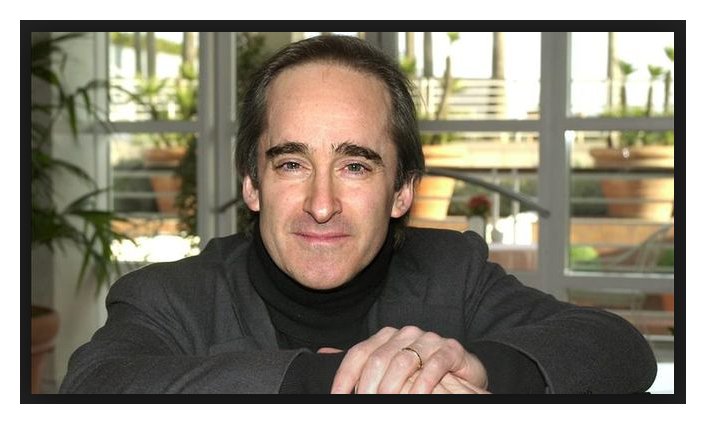

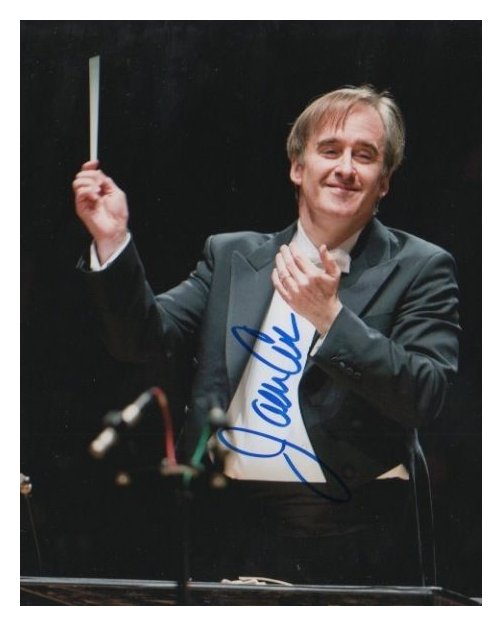

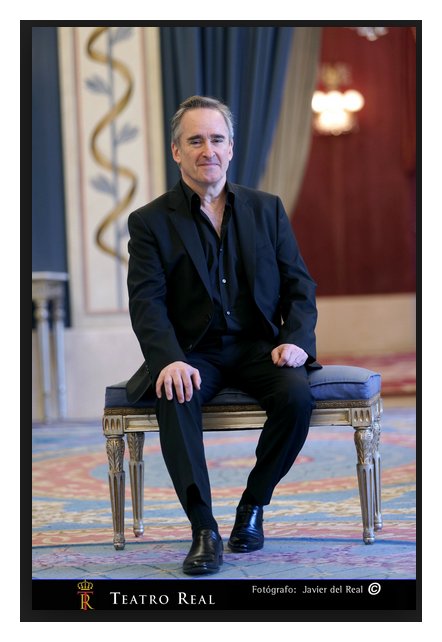

James Conlon

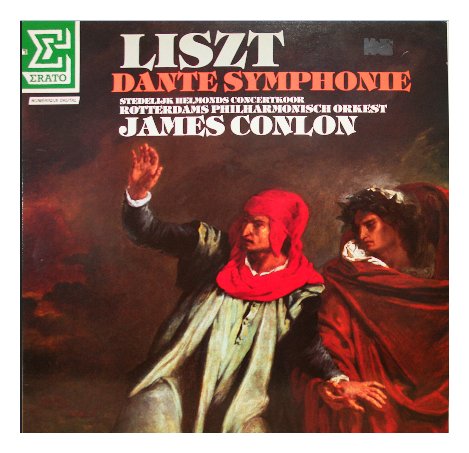

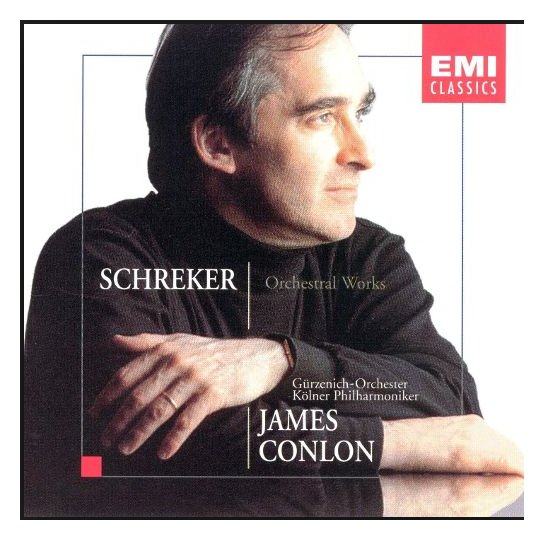

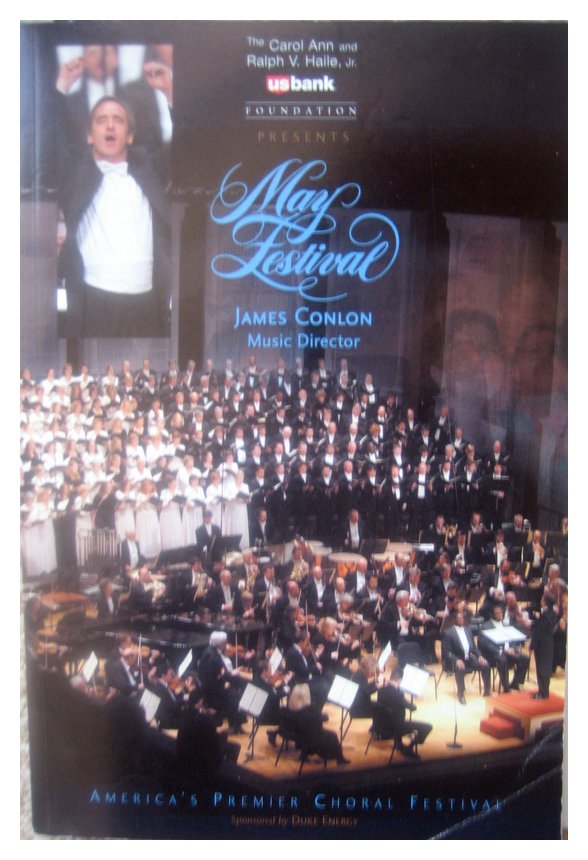

James Conlon (March 18, 1950 - ) is Music Director of the Los Angeles Opera and Principal Conductor of the RAI National Symphony Orchestra in Torino, Italy, where he is the first American to hold the position in the orchestra’s 84-year history. He served as Music Director of the Cincinnati May Festival for 37 years (1979–2016) holding one of the longest tenures of any director of an American classical music institution, and is now Conductor Laureate. Mr. Conlon has also served as Music Director of the Ravinia Festival, summer home of the Chicago Symphony (2006–15); Principal Conductor of the Paris National Opera (1995–2004); General Music Director of the City of Cologne, Germany (1989–2002), where he was Music Director of both the Gürzenich Orchestra Cologne and the Cologne Opera; and Music Director of the Rotterdam Philharmonic (1983–91). He has conducted more than 270 performances at the Metropolitan Opera since his debut there in 1976. He has also conducted at Teatro alla Scala, Wiener Staatsoper, Mariinsky Theatre, Royal Opera at Covent Garden in London, Teatro del Opera di Roma, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, and Lyric Opera of Chicago. He is also known for his efforts in reviving music by composers suppressed during the Nazi regime.  Conlon grew up in a family of five children on Cherry

Street in

Douglaston, Queens, New York City. His mother, Angeline L. Conlon, was

a freelance writer. His father was an assistant to the New York City

Commissioner of Labor in the Robert F. Wagner administration. His

siblings were not musically inclined, nor were his parents. When he was

eleven, he went to a production of La

Traviata by an amateur company

founded by the mother of a friend (Edith Mugdan, the mother of the

young Conlon's best friend, Walter Mugdan, and the founder of the North

Shore Opera). He asked for music lessons and became a boy soprano in a

children's chorus in an opera company in Queens. He dreamed about being

a tenor, then a baritone, and even wanted to sing the role of Carmen at

one point. Finally it dawned on him that the only way to do everything

in opera was to become an operatic conductor. Conlon grew up in a family of five children on Cherry

Street in

Douglaston, Queens, New York City. His mother, Angeline L. Conlon, was

a freelance writer. His father was an assistant to the New York City

Commissioner of Labor in the Robert F. Wagner administration. His

siblings were not musically inclined, nor were his parents. When he was

eleven, he went to a production of La

Traviata by an amateur company

founded by the mother of a friend (Edith Mugdan, the mother of the

young Conlon's best friend, Walter Mugdan, and the founder of the North

Shore Opera). He asked for music lessons and became a boy soprano in a

children's chorus in an opera company in Queens. He dreamed about being

a tenor, then a baritone, and even wanted to sing the role of Carmen at

one point. Finally it dawned on him that the only way to do everything

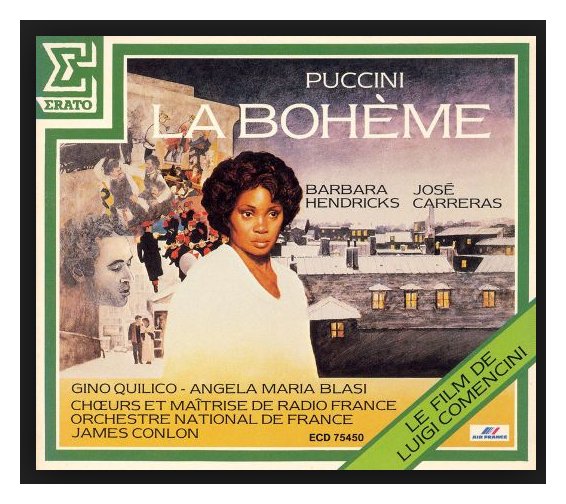

in opera was to become an operatic conductor.He entered the Fiorello H. La Guardia High School of Music & Art at the age of fifteen and at eighteen he was accepted into the Aspen Music Festival and School conducting program, and in September, 1968 he entered The Juilliard School of music. In 1970, the Juilliard Orchestra took an educational tour to Europe and he was invited to Spoleto the next year as an assistant doing work as a répétiteur, coach and chorus conductor. During that time, he conducted one performance of Boris Godunov. He recalled that he had fallen in love with this opera at a young age, and had dreamed that it would be the first opera he would conduct. In 1972, at a scheduled Juilliard production of La Bohème directed by Michael Cacoyannis, conductor Thomas Schippers suddenly pulled out. At the time, Maria Callas was doing a series of master classes at Juilliard and heard Conlon in rehearsal. She suggested to Juilliard's president, Peter Mennin, that Conlon should step in to conduct. Conlon received the conducting award of the American National Orchestral Association and in 1974, and at the invitation of Pierre Boulez, became the youngest conductor engaged for the New York Philharmonic Orchestra's subscription series. In 1976 he made his Metropolitan Opera debut, his British debut with the Scottish Opera, and in 1979 he debuted at Covent Garden. In an effort to raise public consciousness to the significance of works of composers whose lives and compositions were affected by the Holocaust, Conlon has devoted himself to extensive programming of this music in North America and Europe. This includes the works of such composers as Alexander von Zemlinsky, Viktor Ullmann, Pavel Haas, Kurt Weill, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Karl Amadeus Hartmann, Erwin Schulhoff, and Ernst Krenek. In addition to Recovered Voices at LA Opera, as Music Director of the Ravinia Festival, each summer Conlon presented a different composer from this group with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. -- Throughout this page, names which are

links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

James Conlon: [With

a wink] ‘Winding

up’

insinuates that’s

the end of your life! It’s hardly the end of my life! [Both

laugh] I don’t think the fact that I’m young

or an American has to do with it. I don’t like

thinking in national terms either one way or the other.

Europe has been my spiritual base for some time,

and I’m already in my fifth season as the Music Director of

the Rotterdam Philharmonic. So I’ve been living half of my year

in

Holland and a great deal in Paris for quite some time now, and it’s

just a natural extension of that. I’m looking

forward to being the Chief Conductor of an opera house because it’s

probably my first love. Michael Hampe, the Intendant, invited me

when he realized that there was going to be an opening in this

position. He’d been trying to get me to come there on occasions

before, so he found a way to do it on a permanent basis.

James Conlon: [With

a wink] ‘Winding

up’

insinuates that’s

the end of your life! It’s hardly the end of my life! [Both

laugh] I don’t think the fact that I’m young

or an American has to do with it. I don’t like

thinking in national terms either one way or the other.

Europe has been my spiritual base for some time,

and I’m already in my fifth season as the Music Director of

the Rotterdam Philharmonic. So I’ve been living half of my year

in

Holland and a great deal in Paris for quite some time now, and it’s

just a natural extension of that. I’m looking

forward to being the Chief Conductor of an opera house because it’s

probably my first love. Michael Hampe, the Intendant, invited me

when he realized that there was going to be an opening in this

position. He’d been trying to get me to come there on occasions

before, so he found a way to do it on a permanent basis.

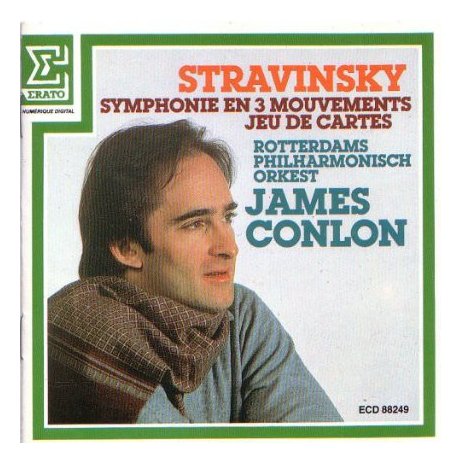

BD: Knowing that

Stravinsky himself has said

that, do you approach Stravinsky’s music any differently than other

composers?

BD: Knowing that

Stravinsky himself has said

that, do you approach Stravinsky’s music any differently than other

composers? BD: Is this what

contributes to the greatness of a

work? That it transcends not only the time but the various looks

at it, and views towards it?

BD: Is this what

contributes to the greatness of a

work? That it transcends not only the time but the various looks

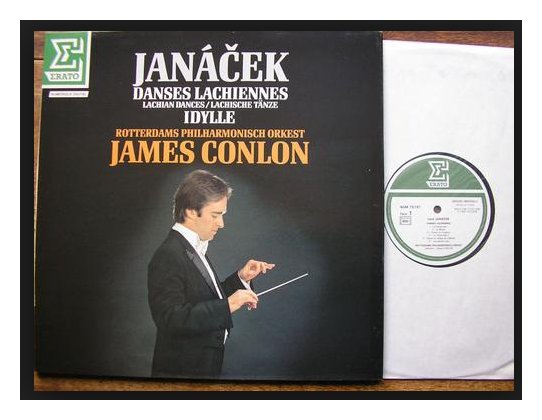

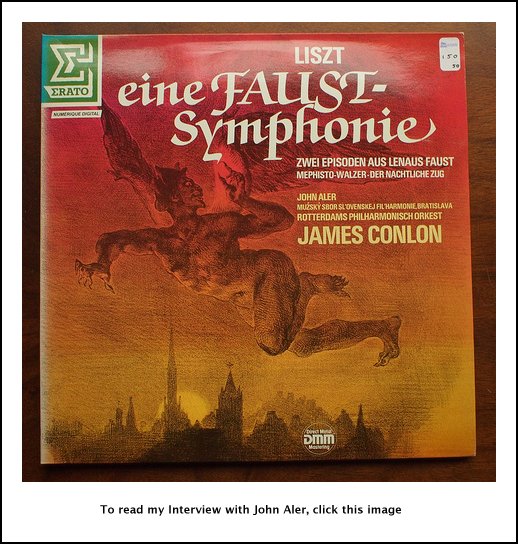

at it, and views towards it? JC: Technically,

yes. The interpretative

is no different. The point is always the same — to

transmit the

work from composition through yourself to a hearer. It’s just

that the form of reception is different. When you’re in the

theater, there’s a proscenium, there’s an orchestra pit, there’s a

theater which is dark. You see a stage and you hear a sound

coming from below. That’s one setting. You know that

setting, so you learn to handle it technically in such a way that the

recipient — the audience — receives

the impression that you’re trying

to communicate to them. The recording is a slightly different

version of that. The recording is designed differently because a

person can hear it anywhere as long as they have the apparatus.

So presumably they’re sitting in their home where there are two

speakers. There’s nothing visual, and you have to get that

across, which can be more difficult and easier. On the one hand

you can say the person chooses that particular record at the

moment, so there need be no distractions. It does

not have to be shared with other persons. On the other hand,

one’s own home can be very distracting, so your challenge

there is to make that speak without the immediacy of the live

performance, and that’s the most important thing. It’s

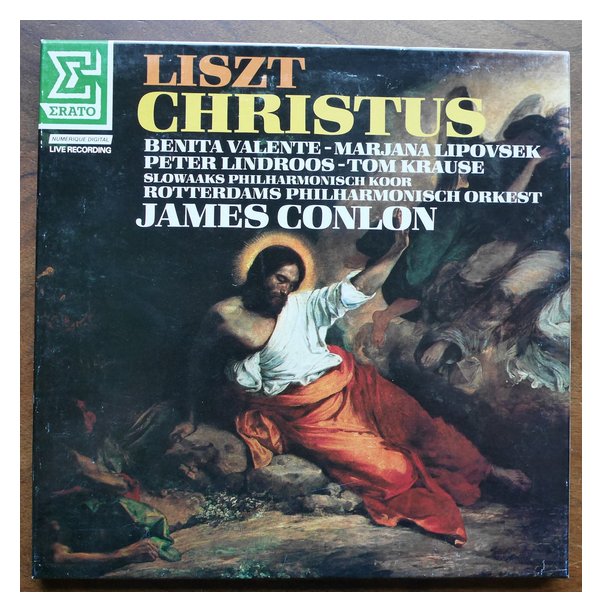

got to seem live. I have only made one live recording, and that

happens to be Christus of

Liszt. I’m

very happy with the results. [Cover

shown at left. See my Interviews with Benita Valente and Tom Krause.]

But when I don’t do a live recording, I

try to make it seem as if it’s live. That is perhaps the most

tricky part of recording because, while you’re doing it and you’re

repeating things several times, it’s very easy for it to lose its

freshness. Part of the success of the

recordings that we’ve made in Rotterdam is that we don’t make them as

studio recordings, where you all meet each other, shake

hands, start the down-beat at 10 o’clock, and you have a finished

record after two sessions. We take music hot off the press.

In other words, we perform it. We perform it as often as we

can, and then we take it while it’s hot. At least for me in my

experience so far, it is ultimately the best way to

make something come to life, because it really is alive. You’re

not just there putting notes down for a microphone.

JC: Technically,

yes. The interpretative

is no different. The point is always the same — to

transmit the

work from composition through yourself to a hearer. It’s just

that the form of reception is different. When you’re in the

theater, there’s a proscenium, there’s an orchestra pit, there’s a

theater which is dark. You see a stage and you hear a sound

coming from below. That’s one setting. You know that

setting, so you learn to handle it technically in such a way that the

recipient — the audience — receives

the impression that you’re trying

to communicate to them. The recording is a slightly different

version of that. The recording is designed differently because a

person can hear it anywhere as long as they have the apparatus.

So presumably they’re sitting in their home where there are two

speakers. There’s nothing visual, and you have to get that

across, which can be more difficult and easier. On the one hand

you can say the person chooses that particular record at the

moment, so there need be no distractions. It does

not have to be shared with other persons. On the other hand,

one’s own home can be very distracting, so your challenge

there is to make that speak without the immediacy of the live

performance, and that’s the most important thing. It’s

got to seem live. I have only made one live recording, and that

happens to be Christus of

Liszt. I’m

very happy with the results. [Cover

shown at left. See my Interviews with Benita Valente and Tom Krause.]

But when I don’t do a live recording, I

try to make it seem as if it’s live. That is perhaps the most

tricky part of recording because, while you’re doing it and you’re

repeating things several times, it’s very easy for it to lose its

freshness. Part of the success of the

recordings that we’ve made in Rotterdam is that we don’t make them as

studio recordings, where you all meet each other, shake

hands, start the down-beat at 10 o’clock, and you have a finished

record after two sessions. We take music hot off the press.

In other words, we perform it. We perform it as often as we

can, and then we take it while it’s hot. At least for me in my

experience so far, it is ultimately the best way to

make something come to life, because it really is alive. You’re

not just there putting notes down for a microphone. JC: Titans are

models to all of us. To speak of aspiring, no, because you cannot

be somebody other

than yourself, even if you want to, and you should not really want

to. Role models are

very important when you are a young person, a child or a

teenager. They are

inspiring. But as you get old, you see more that art is a

very peculiar, specific combination of individual time and place.

You have to accept your place, and know your own strengths and

your own limitations at any point in life to make great art. Yes,

I absolutely adore Toscanini, and he will always be

a model to me of absolute complete commitment to his work,

and his incredible technical means in which to achieve it, and his

personality. He will always be inspiring to

me. But the danger is when

you start to try to imitate, or even value limitation. Yes,

we do imitate unconsciously, just the way we

learn our own language. We don’t learn it because we understand

the grammar. We imitate out parents and certain people we

hear around us, and gradually we find what we want to say in

time. There’s nothing wrong with starting with

imitation. That’s the natural way to develop

as a musician. But in the end, we have found out own peculiar and

particular relationship with those compositions, and we come back to

subjectivity questions again. It will happen

gradually in and of its own accord. I don’t say to myself that I

want to be like that man, or I want to conduct like he conducts,

or I want my music to sound the way he wants it. No. You

can use, and should use, great human beings as models for a particular

way to dedicate yourself to a task, but further than that, you

can’t anyway.

JC: Titans are

models to all of us. To speak of aspiring, no, because you cannot

be somebody other

than yourself, even if you want to, and you should not really want

to. Role models are

very important when you are a young person, a child or a

teenager. They are

inspiring. But as you get old, you see more that art is a

very peculiar, specific combination of individual time and place.

You have to accept your place, and know your own strengths and

your own limitations at any point in life to make great art. Yes,

I absolutely adore Toscanini, and he will always be

a model to me of absolute complete commitment to his work,

and his incredible technical means in which to achieve it, and his

personality. He will always be inspiring to

me. But the danger is when

you start to try to imitate, or even value limitation. Yes,

we do imitate unconsciously, just the way we

learn our own language. We don’t learn it because we understand

the grammar. We imitate out parents and certain people we

hear around us, and gradually we find what we want to say in

time. There’s nothing wrong with starting with

imitation. That’s the natural way to develop

as a musician. But in the end, we have found out own peculiar and

particular relationship with those compositions, and we come back to

subjectivity questions again. It will happen

gradually in and of its own accord. I don’t say to myself that I

want to be like that man, or I want to conduct like he conducts,

or I want my music to sound the way he wants it. No. You

can use, and should use, great human beings as models for a particular

way to dedicate yourself to a task, but further than that, you

can’t anyway.  JC: Oh,

absolutely! I’m doing

this because this is also my spiritual life. This is not just my

income, and it’s not just a way to make a career. This is

what I would have done had I made no money at it! To me,

it’s an entire life. It’s a spiritual way of life, and

curiously, as you speak of the public, that’s what I could feel in the

Soviet Union. That was my perception. Perhaps Germany is

another country where I feel the public is

particularly appreciative because they listen to music more

than they’re interested in the performer. I don’t think that

the German public is so interested in who is performing. They’re

very interested in hearing what is being performed, and they listen to

music much more metaphysically than we do. For whatever reason,

they are trained to think while they

hear, to feel and to think and reflect. It’s very

interesting to talk to people in Germany about their feelings about

particular pieces of music because they will conjure up images of

nature or life experiences or philosophical viewpoints. You see

that it’s living in general, relative to other aspects of life.

That’s where I go away again from the word ‘entertainment’, and why I

don’t like it. Entertainment to me is something you do to

distract somebody from perhaps what is meaningful in life. That’s

not

my point at all. My point is just exactly the opposite.

It’s to focus other persons and focus myself on what is most

meaningful in life.

JC: Oh,

absolutely! I’m doing

this because this is also my spiritual life. This is not just my

income, and it’s not just a way to make a career. This is

what I would have done had I made no money at it! To me,

it’s an entire life. It’s a spiritual way of life, and

curiously, as you speak of the public, that’s what I could feel in the

Soviet Union. That was my perception. Perhaps Germany is

another country where I feel the public is

particularly appreciative because they listen to music more

than they’re interested in the performer. I don’t think that

the German public is so interested in who is performing. They’re

very interested in hearing what is being performed, and they listen to

music much more metaphysically than we do. For whatever reason,

they are trained to think while they

hear, to feel and to think and reflect. It’s very

interesting to talk to people in Germany about their feelings about

particular pieces of music because they will conjure up images of

nature or life experiences or philosophical viewpoints. You see

that it’s living in general, relative to other aspects of life.

That’s where I go away again from the word ‘entertainment’, and why I

don’t like it. Entertainment to me is something you do to

distract somebody from perhaps what is meaningful in life. That’s

not

my point at all. My point is just exactly the opposite.

It’s to focus other persons and focus myself on what is most

meaningful in life.  JC: [Laughs] I

don’t know. I can’t

answer that question. The

first opera I ever saw was Traviata.

My whole concept of life in

music has been with Verdi there at the inception. I

cannot imagine my life without Verdi, and I cannot imagine music

without Verdi. This is why I still find it surprising when I meet

musicians from time to time who don’t like

Verdi, or who think Verdi’s career started with Otello [his penultimate opera] and

finished

with Falstaff; or who simply

don’t understand the art form, or can’t

get interested in it. I’m not saying anything new when I say

Verdi

is not only the pinnacle of Italian music in the operatic

tradition, but he was a great dramatic prophet. For me he is the

Shakespeare of opera. He transformed this

tradition in the course of his long lifetime, and he left works of art

behind for the rest of us to contemplate forever, and for which the

beauty and the dramatic meaning and the human meaning is

fathomless. I compare him to Shakespeare not because of his

own great love for Shakespeare, which was

self-evident, but because of

all the Italian composers — well, of all the

opera composers — he seems

to be the man who was most capable of having at once empathy with his

characters and distance from them. Like Shakespeare, he can

go in and out of the first person to the third person with such ease

and such control that it is hard, at the end of Verdi’s lifetime, to

know

what Verdi really thought, or how he felt, or what his

viewpoint was on this or that. Every

character is so well delineated. Every character is so much in

entity in and out of themselves that they are real. Do they

speak for Verdi? We don’t even know. We don’t really know

what Shakespeare thought. You could quote Shakespeare endlessly,

but Shakespeare is that same type of

transcendent genius who seems to be able to empathize with everybody

and everything on a very real basis, and then also be able to pass to a

metaphysic plane so easily that they see beyond themselves,

and beyond our time, and beyond all the limitations. Is there a

secret to Verdi? No. There is only acquaintance

with Verdi, but real acquaintance with Verdi is the

pre-requisite of conducting Verdi. I’m not speaking of the

technical ability, which has to be considerable because it’s not

easy. It demands a combination of precision and heart, and

flexibility that makes rendering Verdi much more difficult than

rendering a symphony. You have to know

the voice. You have to know Italian. You have to know the

theater. But most of all, you have to know life and

humanity. Nothing is irrelevant in Verdi. Every aspect of

life becomes relevance in performing Verdi. You can’t just drop

in and

say you’d like to conduct a piece by Verdi and start. I’d say

you’d have to be born into it. I

don’t mean that literally, but you have to live with

Verdi. You have to live with the Italian operatic tradition as

well. You really

have to live with it. It’s not something you can just pay a visit

to from time to time. You have to live with it and live in it for

a

long time.

JC: [Laughs] I

don’t know. I can’t

answer that question. The

first opera I ever saw was Traviata.

My whole concept of life in

music has been with Verdi there at the inception. I

cannot imagine my life without Verdi, and I cannot imagine music

without Verdi. This is why I still find it surprising when I meet

musicians from time to time who don’t like

Verdi, or who think Verdi’s career started with Otello [his penultimate opera] and

finished

with Falstaff; or who simply

don’t understand the art form, or can’t

get interested in it. I’m not saying anything new when I say

Verdi

is not only the pinnacle of Italian music in the operatic

tradition, but he was a great dramatic prophet. For me he is the

Shakespeare of opera. He transformed this

tradition in the course of his long lifetime, and he left works of art

behind for the rest of us to contemplate forever, and for which the

beauty and the dramatic meaning and the human meaning is

fathomless. I compare him to Shakespeare not because of his

own great love for Shakespeare, which was

self-evident, but because of

all the Italian composers — well, of all the

opera composers — he seems

to be the man who was most capable of having at once empathy with his

characters and distance from them. Like Shakespeare, he can

go in and out of the first person to the third person with such ease

and such control that it is hard, at the end of Verdi’s lifetime, to

know

what Verdi really thought, or how he felt, or what his

viewpoint was on this or that. Every

character is so well delineated. Every character is so much in

entity in and out of themselves that they are real. Do they

speak for Verdi? We don’t even know. We don’t really know

what Shakespeare thought. You could quote Shakespeare endlessly,

but Shakespeare is that same type of

transcendent genius who seems to be able to empathize with everybody

and everything on a very real basis, and then also be able to pass to a

metaphysic plane so easily that they see beyond themselves,

and beyond our time, and beyond all the limitations. Is there a

secret to Verdi? No. There is only acquaintance

with Verdi, but real acquaintance with Verdi is the

pre-requisite of conducting Verdi. I’m not speaking of the

technical ability, which has to be considerable because it’s not

easy. It demands a combination of precision and heart, and

flexibility that makes rendering Verdi much more difficult than

rendering a symphony. You have to know

the voice. You have to know Italian. You have to know the

theater. But most of all, you have to know life and

humanity. Nothing is irrelevant in Verdi. Every aspect of

life becomes relevance in performing Verdi. You can’t just drop

in and

say you’d like to conduct a piece by Verdi and start. I’d say

you’d have to be born into it. I

don’t mean that literally, but you have to live with

Verdi. You have to live with the Italian operatic tradition as

well. You really

have to live with it. It’s not something you can just pay a visit

to from time to time. You have to live with it and live in it for

a

long time. BD: Did you have any

input at all into what you see,

or just what you hear?

BD: Did you have any

input at all into what you see,

or just what you hear?|

James Conlon at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1987-88 Forza del Destino - with Susan Dunn, Giacomini, Nucci, Kavrakos, Sharon Graham, Andreolli; Maestrini, Schuler (lighting) 1988-89 - Falstaff - with Wixell, Daniels, Corbelli, Walker, Horne, Swensen, Hadley; Ponnelle (original prod)/Calabria, Schuler 1989-90 - Don Carlo - with Rosenshein, TeKanawa, Troyoanos, Hynninen, Ramey; Frisell (dir), Quaranta (des), Schuler 1992-93 - Pelléas et Mélisande - with Esham/Stratas, Hadley, Braun, Kavrakos, Minton; Galati (dir), Israel (des), Schuler |

JC: Yes.

My own preference from all the versions at the moment — and

I underline

‘at the moment’ because it changes — is to do

the Italian four act

version. I have done it with the Fontainebleau act. In

fact, it was my

first opera at Covent Garden and on that occasion I did all five acts

and opened with the opening chorus, which had only then been recently

rediscovered. On that occasion I had

an

interesting experience. The soprano twice was taken ill at the

last moment, and we had to fly somebody in. In one case it was

Gwyneth Jones, and we held up the performance until her

helicopter arrived. Needless to say that kind of

experience was one where you shake hands and say, “See

you down

there.” She didn’t know Fontainebleau, so

we simply cut

it. This happened again, and Martina Arroyo

helped us out

over another performance, and she also didn’t know Fontainebleau, so we

didn’t do it. So I had an opportunity to see performances

back-to-back of

the same production with the same cast with or

without Fontainebleau. I was amazed that my instinct came up

with something that my intellect rejected, which is it is better in

four acts.

JC: Yes.

My own preference from all the versions at the moment — and

I underline

‘at the moment’ because it changes — is to do

the Italian four act

version. I have done it with the Fontainebleau act. In

fact, it was my

first opera at Covent Garden and on that occasion I did all five acts

and opened with the opening chorus, which had only then been recently

rediscovered. On that occasion I had

an

interesting experience. The soprano twice was taken ill at the

last moment, and we had to fly somebody in. In one case it was

Gwyneth Jones, and we held up the performance until her

helicopter arrived. Needless to say that kind of

experience was one where you shake hands and say, “See

you down

there.” She didn’t know Fontainebleau, so

we simply cut

it. This happened again, and Martina Arroyo

helped us out

over another performance, and she also didn’t know Fontainebleau, so we

didn’t do it. So I had an opportunity to see performances

back-to-back of

the same production with the same cast with or

without Fontainebleau. I was amazed that my instinct came up

with something that my intellect rejected, which is it is better in

four acts. JC: It can be

fun. ‘Fun’ is too

limiting a

word because it’s a life’s activity for me, so that means it has all

the aspects of life. It can be hard, it can be easy, it can be

sad, it can be frustrating, it can be annoying, it can be uplifting, it

can be tragic, it can fun! I work all my life and so it’s like a

mosaic.

JC: It can be

fun. ‘Fun’ is too

limiting a

word because it’s a life’s activity for me, so that means it has all

the aspects of life. It can be hard, it can be easy, it can be

sad, it can be frustrating, it can be annoying, it can be uplifting, it

can be tragic, it can fun! I work all my life and so it’s like a

mosaic. BD: Is that what

we’re getting away from now — are composers

trying to write for the ages, instead of writing for today?

BD: Is that what

we’re getting away from now — are composers

trying to write for the ages, instead of writing for today?

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 26, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following July, and again in 1989, 1990, 1995 and 2000. This transcription was made in 2016, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.