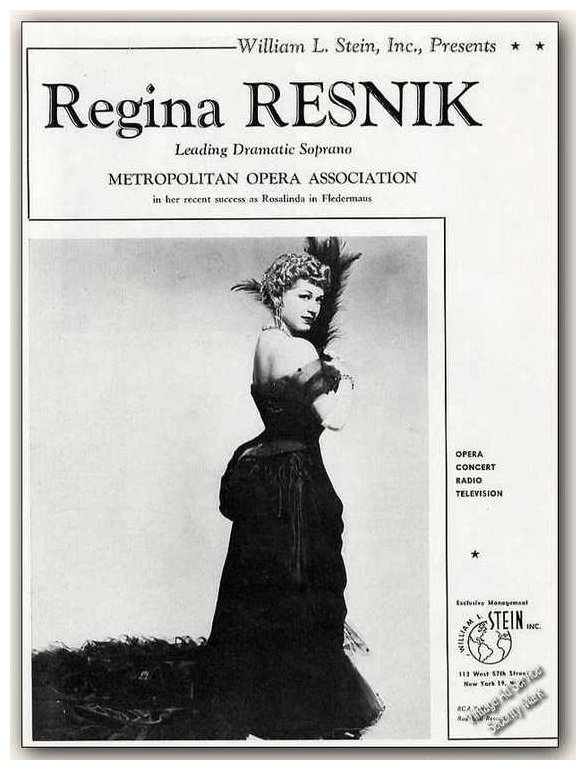

Regina Resnik is one among a very few artists who has enjoyed two internationally successful singing careers, first as a soprano, and later as a mezzo-soprano. In both repertoires, she was noted for her outstanding musicianship and superb dramatic abilities.  She was born in 1922 in New York to Russian immigrant parents. Preparing

herself for a singing career from an early age, she graduated from Hunter

College in 1942. That same year, she made her operatic debut with the New

Opera Company in New York, and immediately set off on a cross-country tour,

performing a series of concerts under the auspices of Pryor Concert Management.

She was born in 1922 in New York to Russian immigrant parents. Preparing

herself for a singing career from an early age, she graduated from Hunter

College in 1942. That same year, she made her operatic debut with the New

Opera Company in New York, and immediately set off on a cross-country tour,

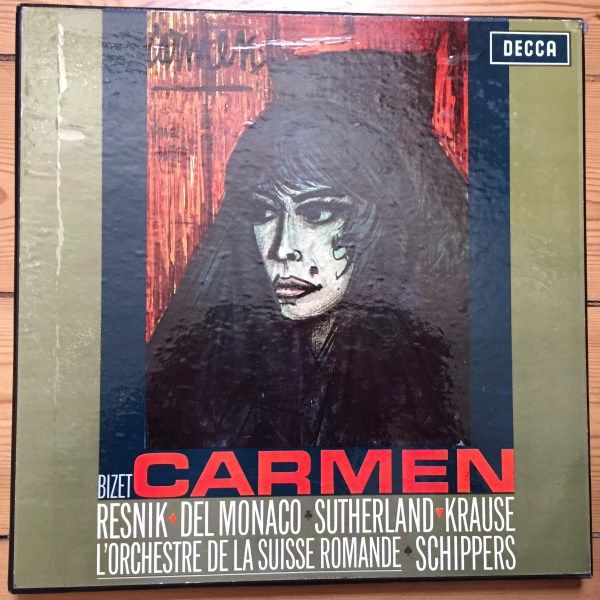

performing a series of concerts under the auspices of Pryor Concert Management.She won the Metropolitan Opera Auditions of the Air in 1944, and made her Metropolitan debut that same season as Leonora in Il Trovatore, replacing an indisposed Zinka Milanov. She rapidly became established as a leading soprano both in the United States and Europe, with a remarkable repertoire ranging from Micaëla and Butterfly to Aïda and Sieglinde. She sang the role of Ellen Orford in the New York premiere of Britten's Peter Grimes. By the mid-1950's, it became clear that her voice was taking on the darker, richer sound of a mezzo-soprano. By 1957, she had learned a new repertoire, and was making her highly successful debut at Covent Garden in the title role of Carmen. This was the beginning of a second career in Europe, with performances in Stuttgart, Berlin, Paris and Vienna. She returned to the Metropolitan Opera as Marina in Boris Godunov, and eventually completed thirty seasons with that company. Her roles included Mistress Quickly, Amneris, Eboli, Herodias, Fricka, Orlovsky, and the title role in Pique Dame. In the 1970's, she began a third career as an opera director, and has directed productions with opera companies around the world. She also conducts master classes at the Metropolitan, San Francisco, Toronto, Paris, Venice, Treviso, and with the Curtis Institute of Music and the Juilliard School of Music. Among her many awards, Mme. Resnik has received honorary doctorates from Hunter College and the New England Conservatory. She has served as a member of the jury of the Peabody Awards for Radio and Television, and is a member of the Board of Directors of the Metropolitan Opera Guild. |

BD: Does it give you a new perspective, though,

for those who are singing the leading role in the musical comedy, that they

have to go out there and give almost as much as a Carmen every night, night after night

after night?

BD: Does it give you a new perspective, though,

for those who are singing the leading role in the musical comedy, that they

have to go out there and give almost as much as a Carmen every night, night after night

after night? RR: Now we’re not talking about audience anymore.

We’re going to come down to the basic things, including who are the singers

who are going to sing that repertory? Now we’re getting down to smaller

and smaller repertory, not more adventurous repertory. We have fewer

singers for those new roles.

RR: Now we’re not talking about audience anymore.

We’re going to come down to the basic things, including who are the singers

who are going to sing that repertory? Now we’re getting down to smaller

and smaller repertory, not more adventurous repertory. We have fewer

singers for those new roles. RR: I really almost didn’t decide what I was going

to accept and turn down because for a very long time I had only the Met.

I went to Europe in the early fifties as a soprano, and then the late fifties

and early sixties as a mezzo. You must remember that I was singing since

1942, so when things were offered to me, they became part of my repertory

as long as I could study them and sing them at opera houses such as the Met

and San Francisco. My repertory grew because I became a very firm resident

in that company. I did what they were doing, and I did the parts.

There were occasions, especially under Edward Johnson at the very beginning,

when I felt I was being burdened with a lot of work, and I would go and ask

a question and get advice. He would say, “Maybe we can leave that out

for a year or so,” or, “Are you prepared to do this if you have to?”

But we did talk. That’s rare today.

RR: I really almost didn’t decide what I was going

to accept and turn down because for a very long time I had only the Met.

I went to Europe in the early fifties as a soprano, and then the late fifties

and early sixties as a mezzo. You must remember that I was singing since

1942, so when things were offered to me, they became part of my repertory

as long as I could study them and sing them at opera houses such as the Met

and San Francisco. My repertory grew because I became a very firm resident

in that company. I did what they were doing, and I did the parts.

There were occasions, especially under Edward Johnson at the very beginning,

when I felt I was being burdened with a lot of work, and I would go and ask

a question and get advice. He would say, “Maybe we can leave that out

for a year or so,” or, “Are you prepared to do this if you have to?”

But we did talk. That’s rare today. RR: I don’t know what you mean by star singers.

I think regional opera has its place, and must have its place. I remember

years ago when there was no regional opera. I preached the fact that

we needed it. As a matter of fact, it wasn’t a bad idea even though

it’s not all that necessary now. I suggested to the Rockefeller Foundation

a good thirty years ago that we should have the Opera of the Southwest, the

Opera of the Northwest, the Opera of the Midwest, the Opera of the Mideast

and the Opera of the Southeast

— leaving

out the big companies of San Francisco, Chicago, New York, etcetera.

Those regional houses would embrace five or six states, border states, so

that somebody who is born and raised in Utah would know that they could go

eventually from an apprentice program into something else, into Seattle for

example, which would be a regional house. At that point, my idea was

to make the Rockefeller Foundation put together a repertory of ten operas,

paid for by them

— stage director,

producer, leg man, lighting engineer

— so that

every regional house had ten operas for the first ten years, with a new premiere

in each region. Everybody would share productions. It was an idea

before productions were shared. I remember one season where everybody

was laughing their heads off; there were three new productions of Trovatore going at the same time in San

Francisco, Chicago and New York. Nobody was sharing anything!

Now today of course they can’t afford not to share; expenses are so great.

In those days they were all competing with one another. For example,

the New York City Opera was playing Butterfly

the same night as the Met. Now they are really trying to avoid that.

They are working to avoid it, and that’s the way it should be. They

should be complementing each other, not competing with one another.

Now of course, everybody is using everybody else’s sets. There is only

one way to get the money out, and that’s to make it available.

RR: I don’t know what you mean by star singers.

I think regional opera has its place, and must have its place. I remember

years ago when there was no regional opera. I preached the fact that

we needed it. As a matter of fact, it wasn’t a bad idea even though

it’s not all that necessary now. I suggested to the Rockefeller Foundation

a good thirty years ago that we should have the Opera of the Southwest, the

Opera of the Northwest, the Opera of the Midwest, the Opera of the Mideast

and the Opera of the Southeast

— leaving

out the big companies of San Francisco, Chicago, New York, etcetera.

Those regional houses would embrace five or six states, border states, so

that somebody who is born and raised in Utah would know that they could go

eventually from an apprentice program into something else, into Seattle for

example, which would be a regional house. At that point, my idea was

to make the Rockefeller Foundation put together a repertory of ten operas,

paid for by them

— stage director,

producer, leg man, lighting engineer

— so that

every regional house had ten operas for the first ten years, with a new premiere

in each region. Everybody would share productions. It was an idea

before productions were shared. I remember one season where everybody

was laughing their heads off; there were three new productions of Trovatore going at the same time in San

Francisco, Chicago and New York. Nobody was sharing anything!

Now today of course they can’t afford not to share; expenses are so great.

In those days they were all competing with one another. For example,

the New York City Opera was playing Butterfly

the same night as the Met. Now they are really trying to avoid that.

They are working to avoid it, and that’s the way it should be. They

should be complementing each other, not competing with one another.

Now of course, everybody is using everybody else’s sets. There is only

one way to get the money out, and that’s to make it available. RR: I would say that if I had to choose the roles

in the repertory that gave me the greatest all-around satisfaction, which

means interpreter, actress, vocalist, singer, Klytemnestra certainly would

be at the very top. That doesn’t push Carmen away at all; it’s two different

worlds. It cost me more of me to sing one Klytemnestra than two Carmens.

RR: I would say that if I had to choose the roles

in the repertory that gave me the greatest all-around satisfaction, which

means interpreter, actress, vocalist, singer, Klytemnestra certainly would

be at the very top. That doesn’t push Carmen away at all; it’s two different

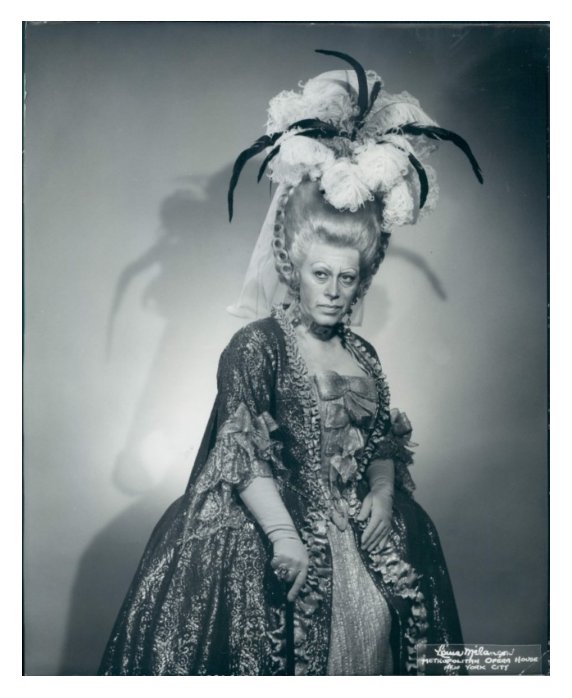

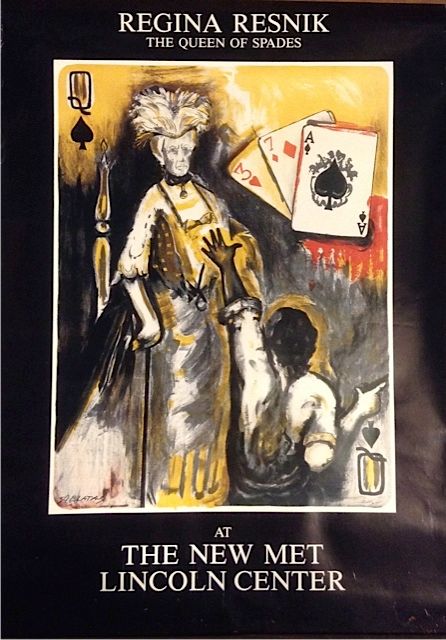

worlds. It cost me more of me to sing one Klytemnestra than two Carmens. RR: Not too many of them, but interesting ones.

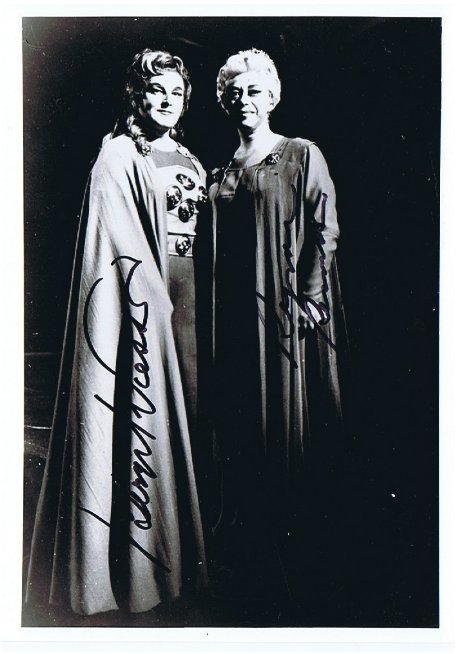

Pique Dame was one, certainly [Photo shown at left]; Klytemnestra, also

the Dialogues of the Carmelites;

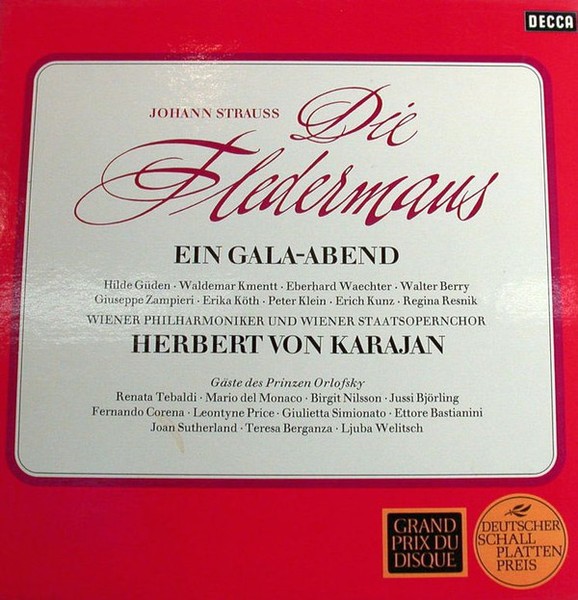

even Prince Orlofsky. The others, of course, were the biggies...

RR: Not too many of them, but interesting ones.

Pique Dame was one, certainly [Photo shown at left]; Klytemnestra, also

the Dialogues of the Carmelites;

even Prince Orlofsky. The others, of course, were the biggies... BD: Unbelievable! Someone should do a great

doctoral dissertation on that brief period in music history.

BD: Unbelievable! Someone should do a great

doctoral dissertation on that brief period in music history. RR: I must say I tried not to. When you had

to repeat a lot, it became tedious and so it wasn’t that fresh anymore.

But very often, the things which are preserved on recordings are very often

my first takes. For example, the Seguidilla

on the Carmen recording is the first

take. The death scene of the countess in Pique Dame with Rostropovich is the rehearsal

take. I sang it once through, and then we put it in the can twice more,

but we used the first one. The entire scene in Elektra with Nilsson was in two takes.

[Photo of Nilsson and Resnik in Tristan

und Isolde (which is autographed by both

artists) is shown at right.] The only thing that I did separately

was the exit and the laughter and all that stuff, which was technical.

Very often, a lot of what I did was right on at the very beginning.

Of course, we were limited to space and microphones and technique. You

couldn’t move around too much, but I tried to make it as feeling as possible,

and as non-technical as possible. The end result often had nothing to

do with the singer; it had a lot to do with the engineers and the mixing of

sound, and all of that sort of stuff.

RR: I must say I tried not to. When you had

to repeat a lot, it became tedious and so it wasn’t that fresh anymore.

But very often, the things which are preserved on recordings are very often

my first takes. For example, the Seguidilla

on the Carmen recording is the first

take. The death scene of the countess in Pique Dame with Rostropovich is the rehearsal

take. I sang it once through, and then we put it in the can twice more,

but we used the first one. The entire scene in Elektra with Nilsson was in two takes.

[Photo of Nilsson and Resnik in Tristan

und Isolde (which is autographed by both

artists) is shown at right.] The only thing that I did separately

was the exit and the laughter and all that stuff, which was technical.

Very often, a lot of what I did was right on at the very beginning.

Of course, we were limited to space and microphones and technique. You

couldn’t move around too much, but I tried to make it as feeling as possible,

and as non-technical as possible. The end result often had nothing to

do with the singer; it had a lot to do with the engineers and the mixing of

sound, and all of that sort of stuff. BD: There used to be the great tradition in Europe

of taking the lead singers who are beyond their prime, and putting them in

small roles so you have the strength and experience there.

BD: There used to be the great tradition in Europe

of taking the lead singers who are beyond their prime, and putting them in

small roles so you have the strength and experience there. RR: It’s going better than I expected. No,

there aren’t too many surprises. I’m having a good time doing it.

I enjoy the character. I would not have taken this musical comedy as

such if it had been Me and My Girl and Forty-second

Street no matter what. The part is excellent. It’s a part

that grows

— it has

a beginning and it has an end. She’s charming, she’s poignant, she’s

cute, she’s tragic. She has a little of everything. It’s an interesting

part. The play has a motivation. It is not just another play,

it’s a good play with a good book.

RR: It’s going better than I expected. No,

there aren’t too many surprises. I’m having a good time doing it.

I enjoy the character. I would not have taken this musical comedy as

such if it had been Me and My Girl and Forty-second

Street no matter what. The part is excellent. It’s a part

that grows

— it has

a beginning and it has an end. She’s charming, she’s poignant, she’s

cute, she’s tragic. She has a little of everything. It’s an interesting

part. The play has a motivation. It is not just another play,

it’s a good play with a good book. RR: Anywhere. It makes no difference where

you sing Wagner, the effort’s the same. Let’s take the difference,

for example, between Verdi and Puccini. Verdi is more difficult on

the voice in the break of the voice because Verdi wrote for the drama, what

he could get out of the drama of the voice. But Puccini stretches the

voice. You need much more stretch in the cords and in your breath to

sing Puccini, especially the tenors. The Puccini tenor is more difficult

than the Verdi tenor. There’s no question that the Rodolfo needs much

more of what I call stretch stamina, than Alfredo in Traviata.

In Wagner it is not the question that you sing longer and it’s more arduous;

it’s do you have the quantity of voice to come over the orchestra for that

long period of time in these long phrases. You have to sing big, long

phrases against a huge orchestra. Wagner and Strauss use a hundred and

twenty-three in the pit at their maximum. But if you have no fear that

you don’t have enough sound, it is another style. You do have to gear

yourself for that much support and push. The way they do it in Bayreuth,

as you brought up the question, is that they give you some time in between.

The intermissions are an hour. I sang Fidelio at Central City in 1949-50.

That house had six hundred and ninety-nine seats and a reduced orchestra.

I didn’t sing it any differently than I sang it at the Met; it’s still your

voice and still Beethoven’s Leonora. You can’t sing less. You’re

singing it the way it is.

RR: Anywhere. It makes no difference where

you sing Wagner, the effort’s the same. Let’s take the difference,

for example, between Verdi and Puccini. Verdi is more difficult on

the voice in the break of the voice because Verdi wrote for the drama, what

he could get out of the drama of the voice. But Puccini stretches the

voice. You need much more stretch in the cords and in your breath to

sing Puccini, especially the tenors. The Puccini tenor is more difficult

than the Verdi tenor. There’s no question that the Rodolfo needs much

more of what I call stretch stamina, than Alfredo in Traviata.

In Wagner it is not the question that you sing longer and it’s more arduous;

it’s do you have the quantity of voice to come over the orchestra for that

long period of time in these long phrases. You have to sing big, long

phrases against a huge orchestra. Wagner and Strauss use a hundred and

twenty-three in the pit at their maximum. But if you have no fear that

you don’t have enough sound, it is another style. You do have to gear

yourself for that much support and push. The way they do it in Bayreuth,

as you brought up the question, is that they give you some time in between.

The intermissions are an hour. I sang Fidelio at Central City in 1949-50.

That house had six hundred and ninety-nine seats and a reduced orchestra.

I didn’t sing it any differently than I sang it at the Met; it’s still your

voice and still Beethoven’s Leonora. You can’t sing less. You’re

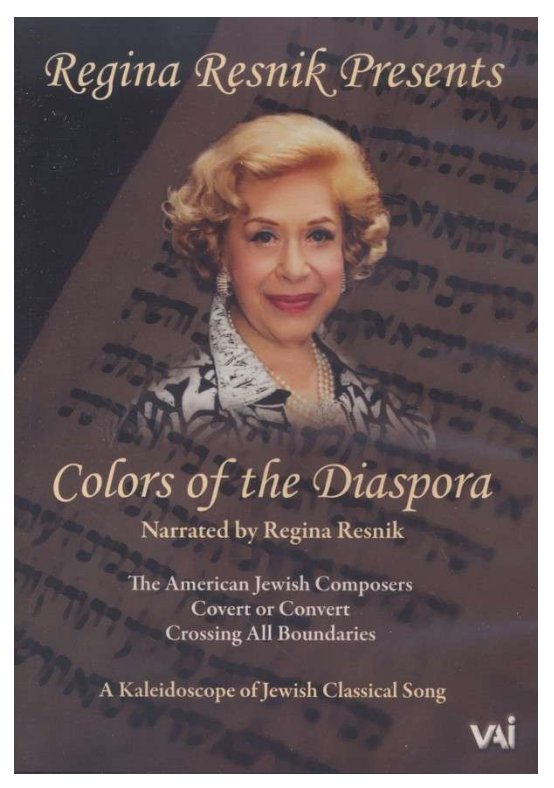

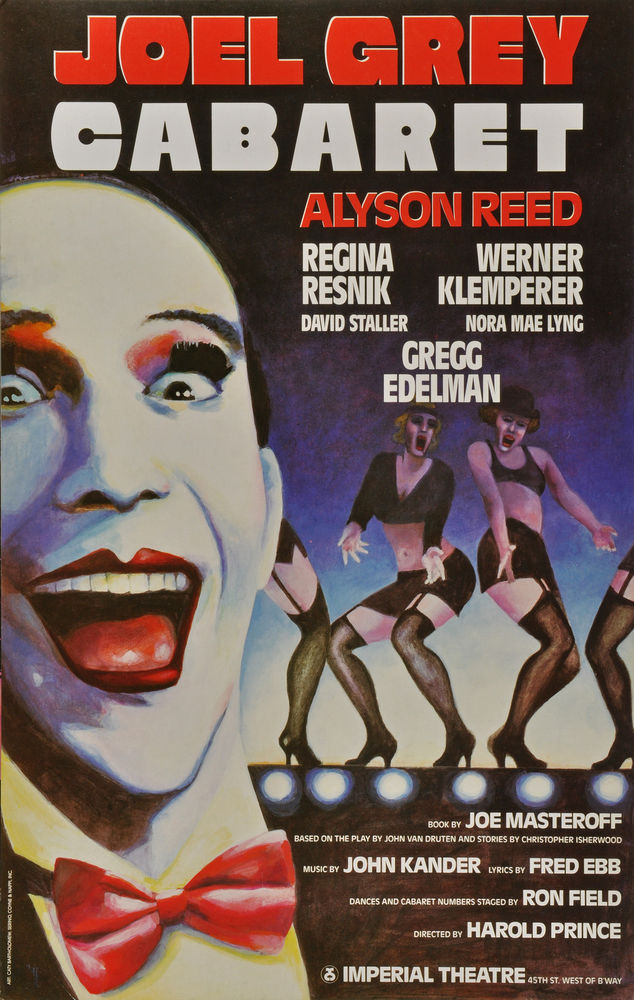

singing it the way it is.| Regina Resnik, renowned opera singer,

stage director, filmmaker and master teacher, was catapulted into operatic

stardom on 24 hours’ notice in 1942, when she appeared as Lady Macbeth with

the New Opera Company of New York, conducted by Fritz Busch. She repeated

the same feat in her Metropolitan Opera debut in 1944, when she sang Leonora

in Il Trovatore. After 13 years as

a leading dramatic soprano, she began a highly esteemed second career as

a mezzo-soprano in 1956, becoming the only singer in operatic history to

have sung the mezzo and soprano leads in half her repertory. Her legendary

musical collaborators include Bernstein, Solti, Karajan, Bruno Walter,

Klemperer, Erich Kleiber, Reiner and Rostropovich. In

a career spanning 60 years and more than 80 parts -- at the Met, San Francisco,

Covent Garden, Vienna, Salzburg, Paris, La Scala, Berlin and Hamburg -- Ms.

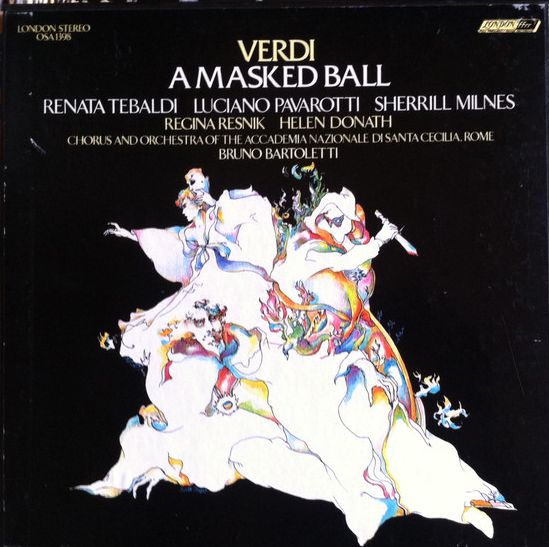

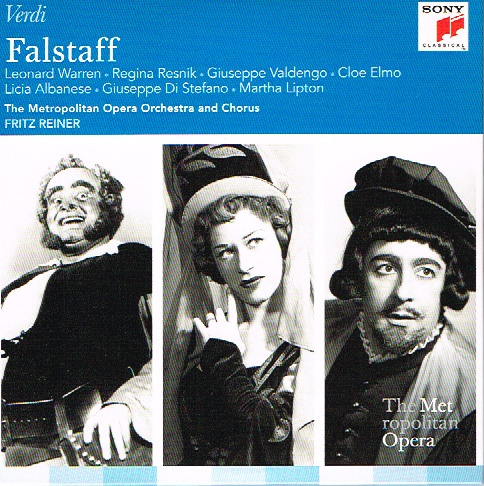

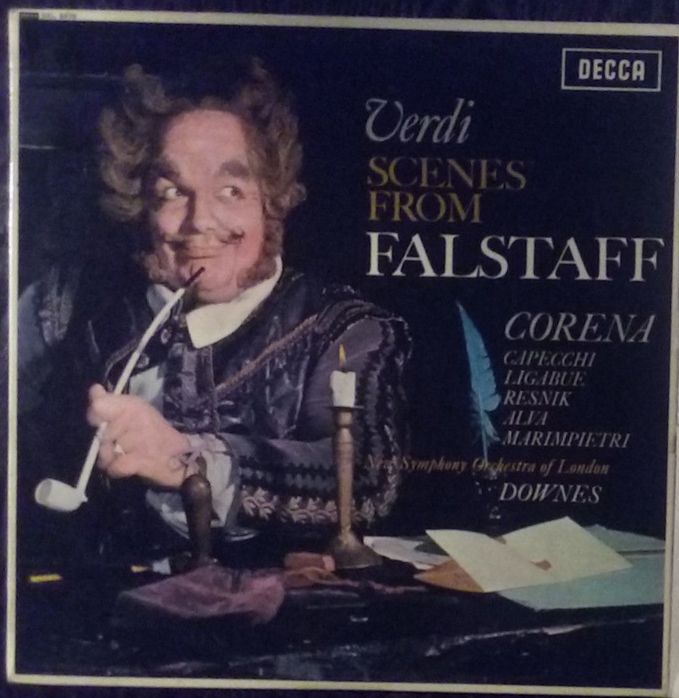

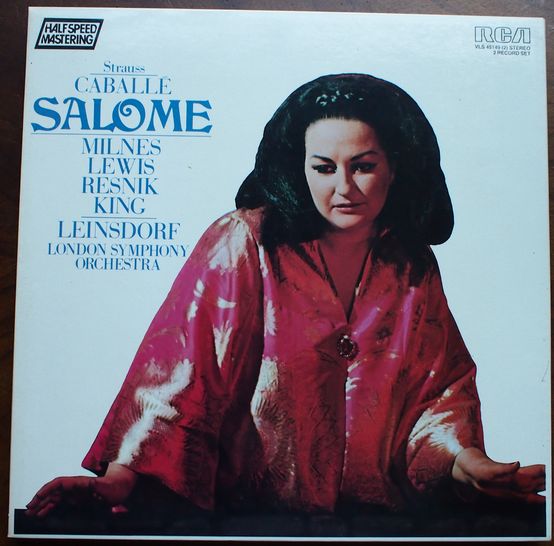

Resnik became synonymous with four roles: Carmen, Mistress Quickly in Falstaff, Klytämnestra in Elektra, and the Countess in The Queen of Spades -- all of which she

recorded and which have become the standard of comparison. With her late husband, the artist Arbit Blatas, as scenic designer, Ms. Resnik directed in such international opera houses as San Francisco, Hamburg, Venice, Sydney, Vancouver and Lisbon from 1971 to 1983. That year she also wrote, produced and directed the prize-winning documentary The Historic Ghetto of Venice. In 1987, her musical theater début as Fraülein Schneider in Cabaret earned her a Tony Nomination, and, in 1990, her Madame Armfeldt in A Little Night Music brought her a Drama Desk Nomination. In 1992, the 50th anniversary of her operatic début was honored in New York, Vienna and Venice. In 2004, The Metropolitan Opera Guild celebrated the 60th anniversary of her Met debut at Lincoln Center, while London Records released a two-CD retrospective of her recordings, entitled Regina Resnik: Dramatic Scenes and Arias. Ms. Resnik is also renowned as a master teacher in the world’s leading young artist programs. In New York, she just completed her eighth year as Master Teacher-in-Residence at the Mannes College at the New School of Music. The opera was Falstaff, prepared for the spring 2011 production at the Kaye Playhouse, Hunter College. In 2009, the New School honored Ms. Resnik with her fourth Honorary Doctorate. From 1993 to 2010, she directed four different programs in Treviso, Italy. Ms. Resnik has also enjoyed prestigious affiliations with the Metropolitan Opera, the Juilliard School, the San Francisco Opera and L'Opéra de la Bastille, among many others. Since 1997, Ms. Resnik has directed and narrated the concert series Regina Resnik Presents, co-founded and co-produced with her son, Michael Philip Davis, both on City University of New York (CUNY) TV and in concerts nationwide. --Biography prepared for her 90th birthday,

August 30, 2012

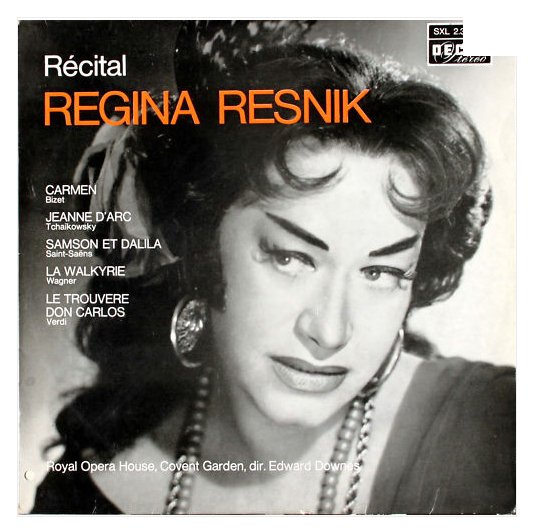

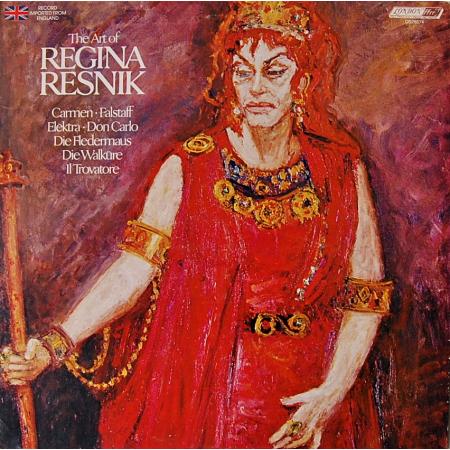

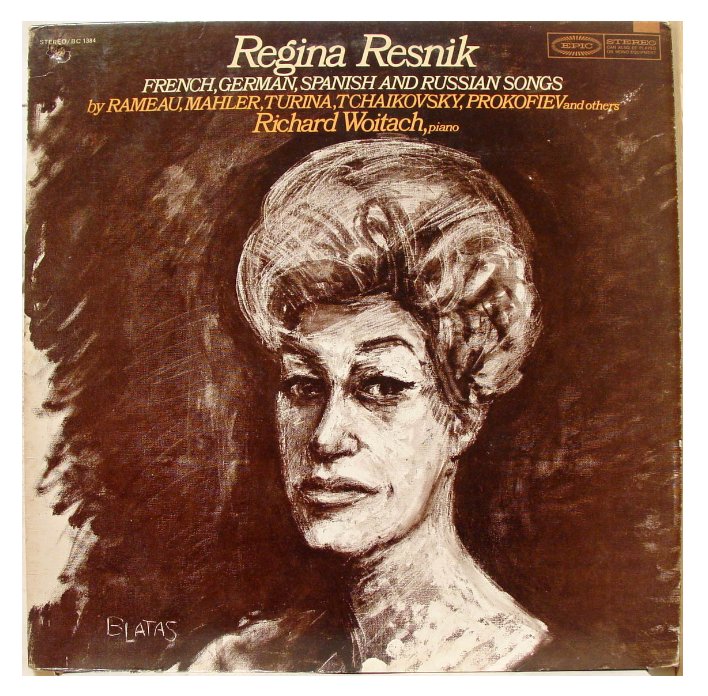

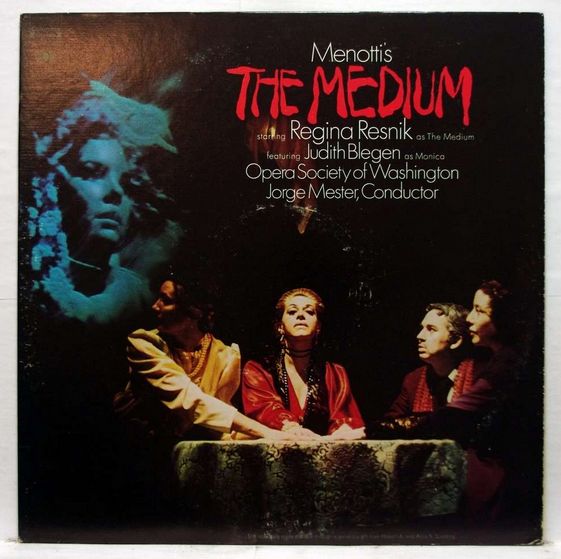

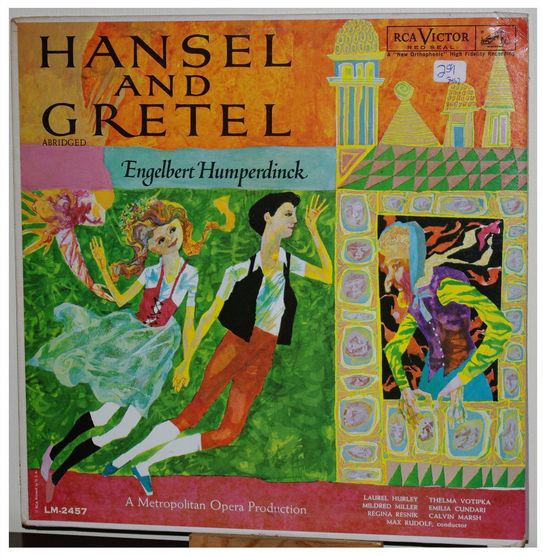

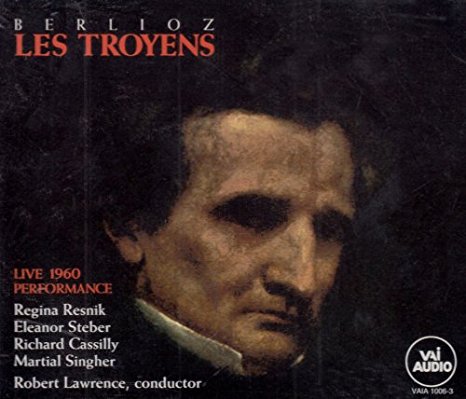

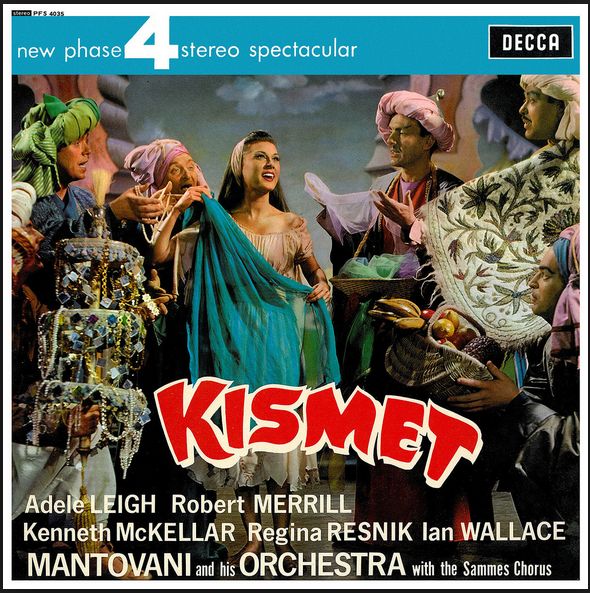

Below are just a few of her other recordings . . .

See my Interviews with Judith Blegen and Jorge Mester

See my Interviews with Tom Krause, and Yvonne Minton (Mercédès)

See my Interviews with Eleanor Steber, and Giorgio Tozzi

See my Interview with Max Rudolf

See my Interviews with Sherrill Milnes, and Helen Donath

See my Interviews with Graziella Sciutti, and Rolando Panerai

See my Interview with Licia Albanese

See my Interview with Renato Capecchi

See my Interviews with James King, and Erich Leinsdorf

See my Interviews with Walter Berry, Giulietta Simionato, and Teresa Berganza

See my Interview with Martial Singher

See my Interviews with Werner Klemperer, and Harold Prince

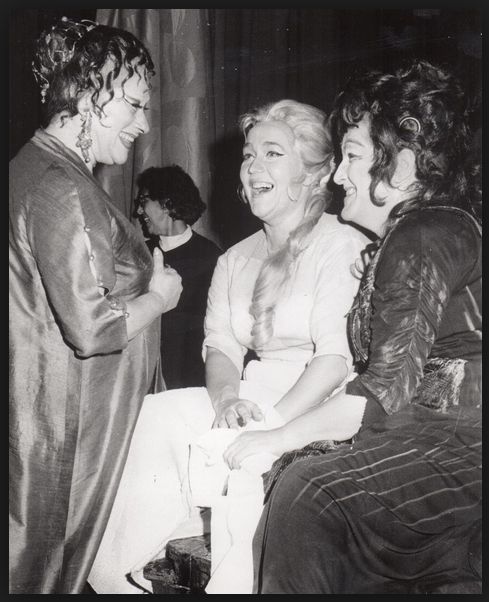

Resnik, Leonie Rysanek, and Birgit Nilsson (l-r) in Elektra at the Met |

This interview was recorded at her hotel in Chicago on March 16, 1987. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB two weeks later and again later that year, as well as in 1990 and 1992. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.