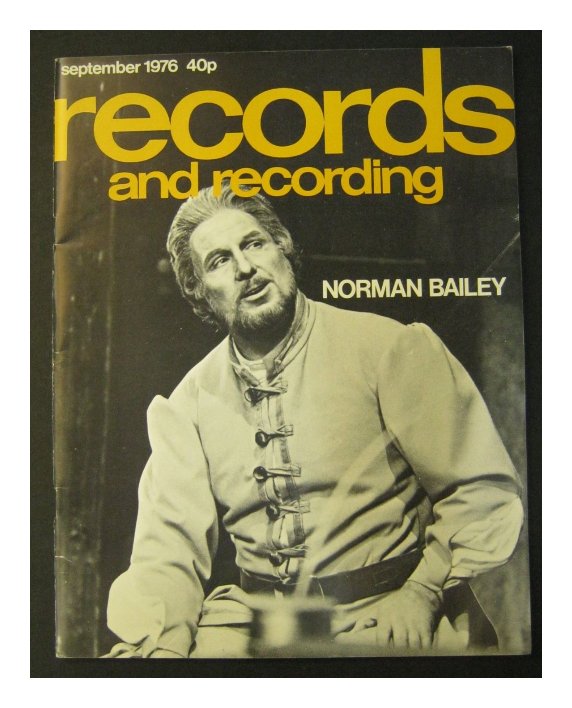

| Following studies at Rhodes University

in South Africa, Norman Bailey continued his musical training at the Vienna

Music Academy, working there with such distinguished pedagogues as Julius

Patzak, Adolf Vogel, and Joseph Witt. In 1959, he made his debut with the

Vienna Chamber Opera in Rossini's one-act La cambiale di matrimonio, singing the

bass role of Tobias Mill. The next year, he began an engagement at Linz. In

1963, he moved to Wuppertal and, from 1964 to 1967, sang at Düsseldorf.

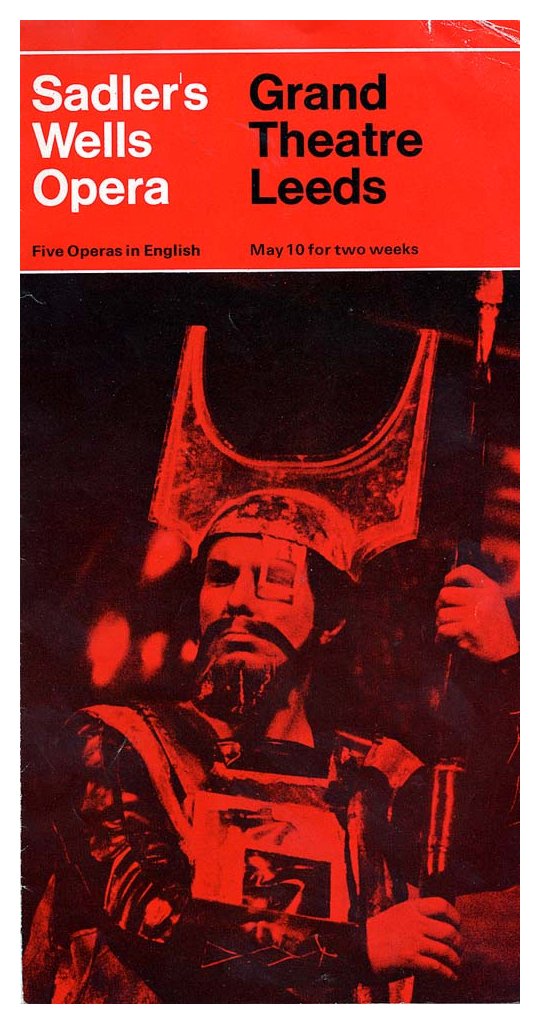

In 1967, Bailey began an association with Sadler's Wells Opera (later the

English National Opera) that led him to international recognition. While his

debut at the "second" London company was as Count Almaviva in Mozart's

Le nozze di Figaro, it was his

Hans Sachs that brought acclaim. Under the tutelage and baton of Reginald Goodall (largely

overlooked by English opera companies until then), Bailey fashioned a sympathetic

character, handsomely and untiringly sung. Not long after, introduced with

a rather patronizing acknowledgement by Sir David Webster, Bailey stepped

in to save a Meistersinger at the

Royal Opera House, leaving critics wondering why he hadn't been engaged there

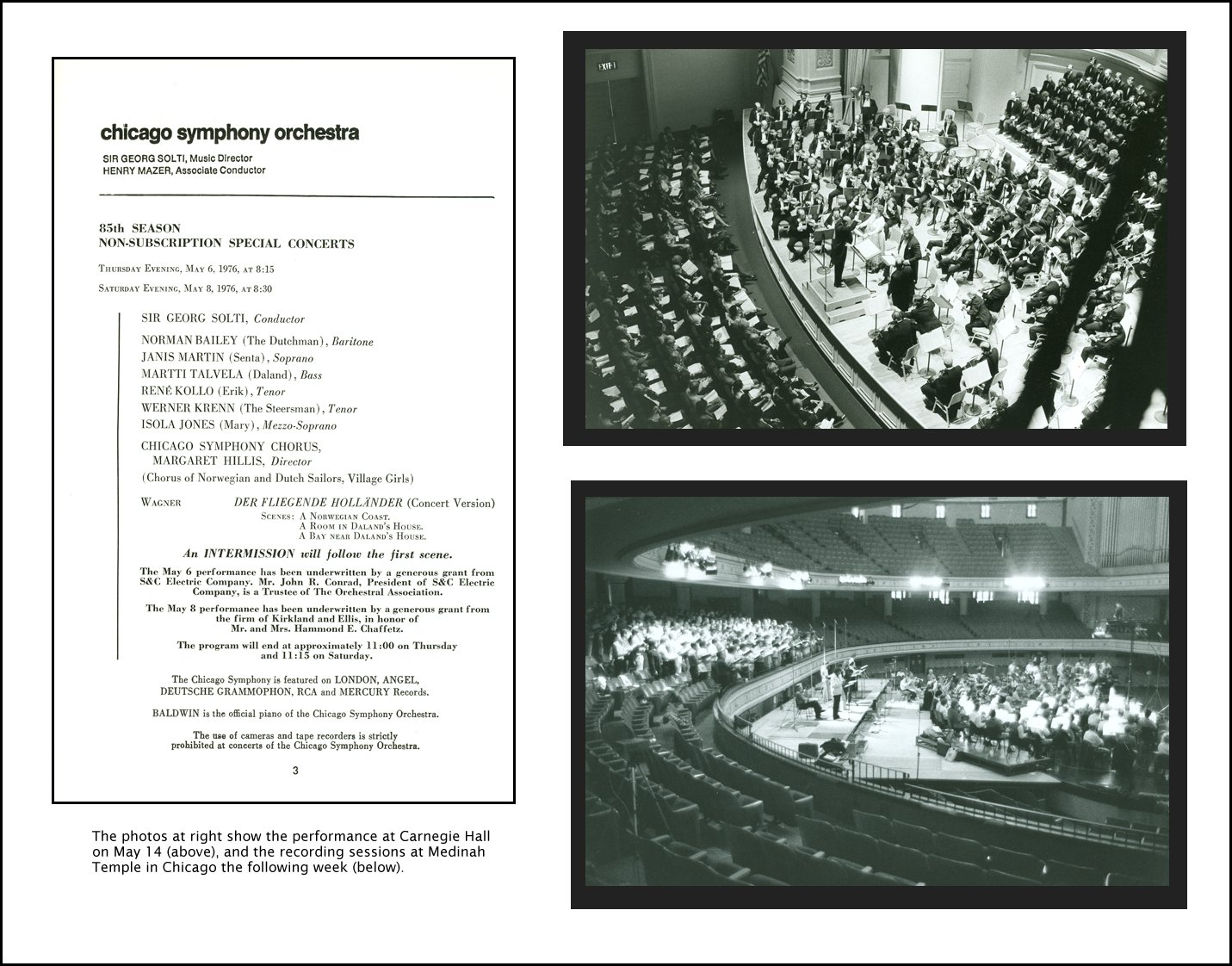

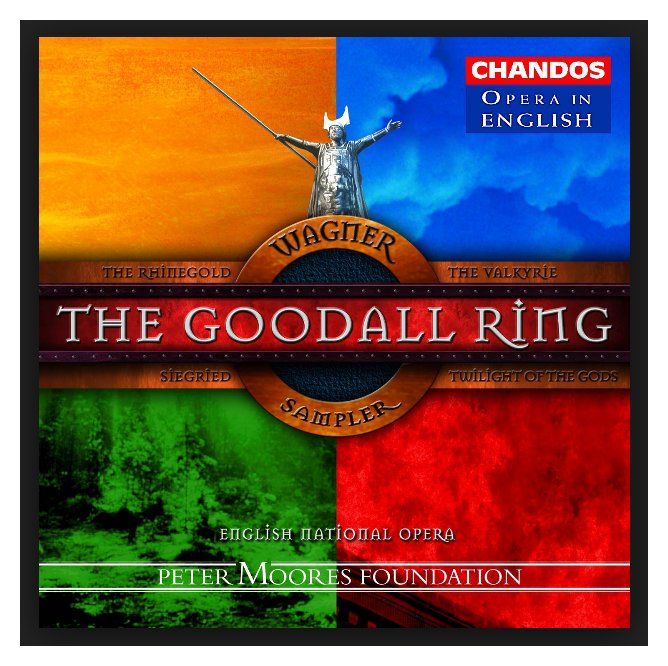

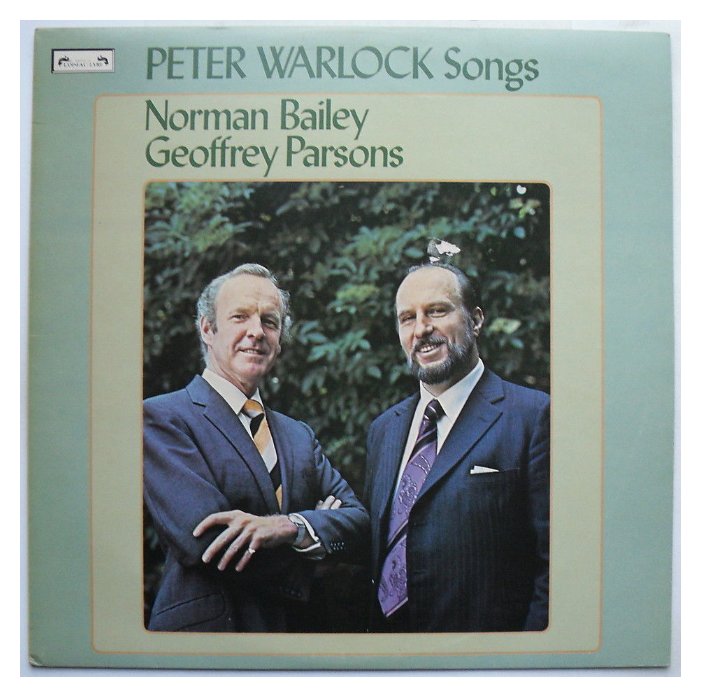

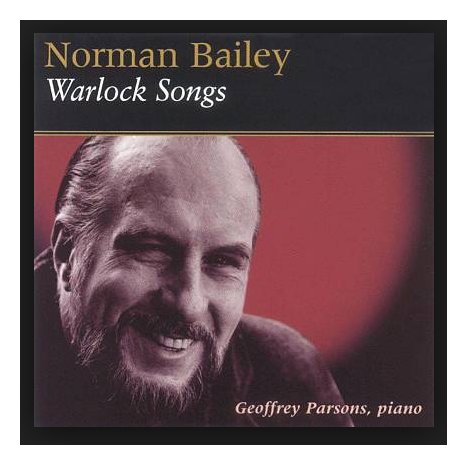

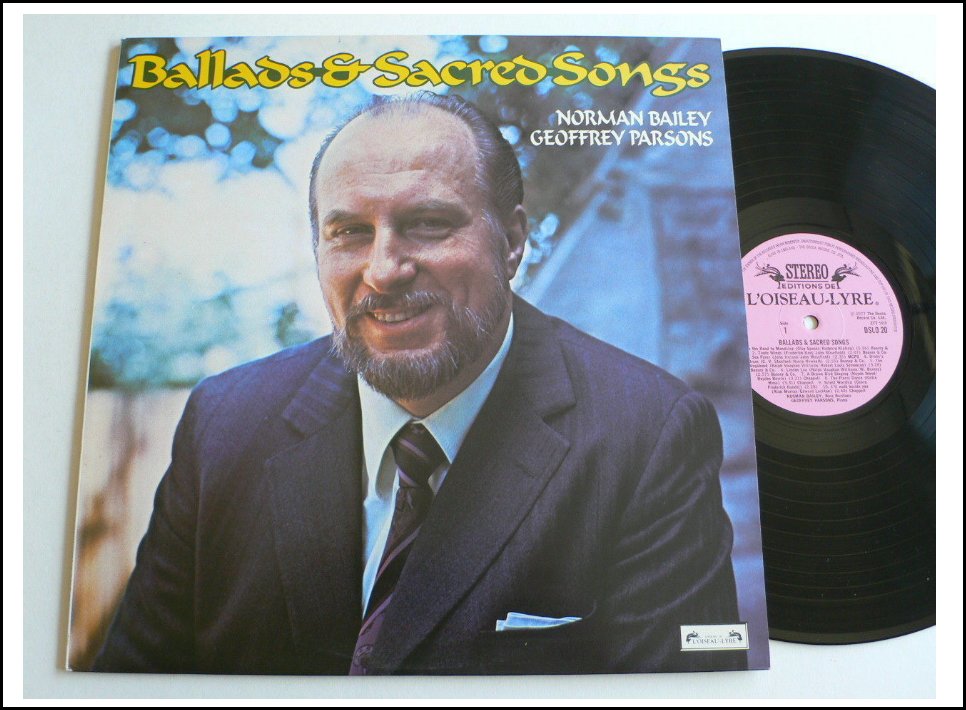

in the first place. The 1970s brought Bailey's Wotan in the ENO's famous English-language Ring at the Coliseum, subsequently recorded and made available once more in the new millennium. [The translation was by Andrew Porter.] His Hans Sachs was heard in such other venues as Brussels, Hamburg, Munich, and New York. In the latter city, Bailey sang the role at the New York City Opera in 1975 and the next year, performed it again for his Metropolitan debut. Bayreuth, meanwhile, had also heard his Amfortas and Gunther. As his fame spread, Bailey returned to some of the Italian roles he had sung upon his move into the baritone range in the 1950s and early '60s. For the English National Opera, he essayed Count di Luna and a few other such true baritone parts before returning to a mix of registers, singing Pizzaro and the Forester in Cunning Little Vixen (bass baritone) and Prince Gremin and Marshall Kutuzov (both bass roles). Bailey's artistic eclecticism led to his being selected to play Dallapiccola's Job for his La Scala debut in 1967 and to his singing Johann Matthys in the 1985 premiere of Alexander Goehr's Behold the Sun at Duisburg. In the 1990s, Bailey sang bass roles for Opera North (the Landgraf and Oroveso). His Glyndebourne Festival debut came in 1996 with an unforgettably seedy portrayal of Schigolch. In 1977 he waa awarded the CBE. Bailey recorded many of his best roles all under major conductors. With Solti, he committed his Hans Sachs and Dutchman to disc. His "English" Wotan under Goodall remains commanding, as does his title role performance in Tippett's King Priam. -- Biography excerpted from an article

by Erik Eriksson

-- Names which are links (both in this box and below) refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD |

NB: [Ponders, then speaks deliberately] No,

I don’t think so. What I said, with humorous works one gains a great

deal from having immediacy of the joke, but it’s a little disconcerting for

the people on stage if the joke is actually on the surtitles before the people

actually said the words, or vice-versa. In actual fact they finish the

joke and then the audience laughs a couple of seconds afterwards because there’s

a delayed reaction! Now I don’t think that [the death of opera-in-English]

will come about, although I think it’s going to widen the audiences.

I think the audiences are going to feel they have great contact with opera.

I think some people are purists. They always enjoy hearing an opera in the

original language because it’s a matter of sound. There’s a certain

flavor of a language; there’s a certain atmosphere one creates with the language,

but with more and more the presentation of surtitles, people are going to

find that they have a far greater contact with that. Though there’s

an argument to be made that even if something is being done in the vernacular,

say it’s being done in English for an Italian or German opera, that some of

the text in actual fact gets lost. So even surtitles there are not going

to beat a miss!

NB: [Ponders, then speaks deliberately] No,

I don’t think so. What I said, with humorous works one gains a great

deal from having immediacy of the joke, but it’s a little disconcerting for

the people on stage if the joke is actually on the surtitles before the people

actually said the words, or vice-versa. In actual fact they finish the

joke and then the audience laughs a couple of seconds afterwards because there’s

a delayed reaction! Now I don’t think that [the death of opera-in-English]

will come about, although I think it’s going to widen the audiences.

I think the audiences are going to feel they have great contact with opera.

I think some people are purists. They always enjoy hearing an opera in the

original language because it’s a matter of sound. There’s a certain

flavor of a language; there’s a certain atmosphere one creates with the language,

but with more and more the presentation of surtitles, people are going to

find that they have a far greater contact with that. Though there’s

an argument to be made that even if something is being done in the vernacular,

say it’s being done in English for an Italian or German opera, that some of

the text in actual fact gets lost. So even surtitles there are not going

to beat a miss! BD: Does all of this, then, enter into your decision

as to whether to accept or turn down a role?

BD: Does all of this, then, enter into your decision

as to whether to accept or turn down a role? BD: He self-imposed this fate?

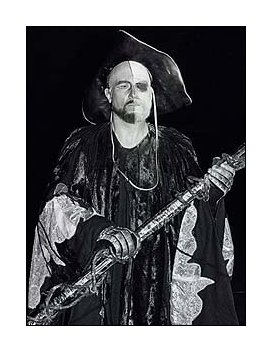

BD: He self-imposed this fate? NB: Yes, but I have a bit of reservation because

that comes into the area of what one should do in warming up the voice.

You then have the part of the Wanderer – another name for Wotan, essentially

– in Siegfried [shown in photo at left]. There the

role is relatively high, and the orchestra is very, very loud. So the

evolution is the progression from Rhinegold

Wotan, which is relatively easy to sing but difficult to portray because

one must dominate without the music to actually present him. You’ve

got Loge and you’re got Alberich who have been given infinitely more music

than Wotan, yet Wotan must establish there that he’s in command – or at any

rate that he thinks he’s in command.

NB: Yes, but I have a bit of reservation because

that comes into the area of what one should do in warming up the voice.

You then have the part of the Wanderer – another name for Wotan, essentially

– in Siegfried [shown in photo at left]. There the

role is relatively high, and the orchestra is very, very loud. So the

evolution is the progression from Rhinegold

Wotan, which is relatively easy to sing but difficult to portray because

one must dominate without the music to actually present him. You’ve

got Loge and you’re got Alberich who have been given infinitely more music

than Wotan, yet Wotan must establish there that he’s in command – or at any

rate that he thinks he’s in command.

BD: So the technique is something that you’ve built,

and then you rely on it and let it run itself?

BD: So the technique is something that you’ve built,

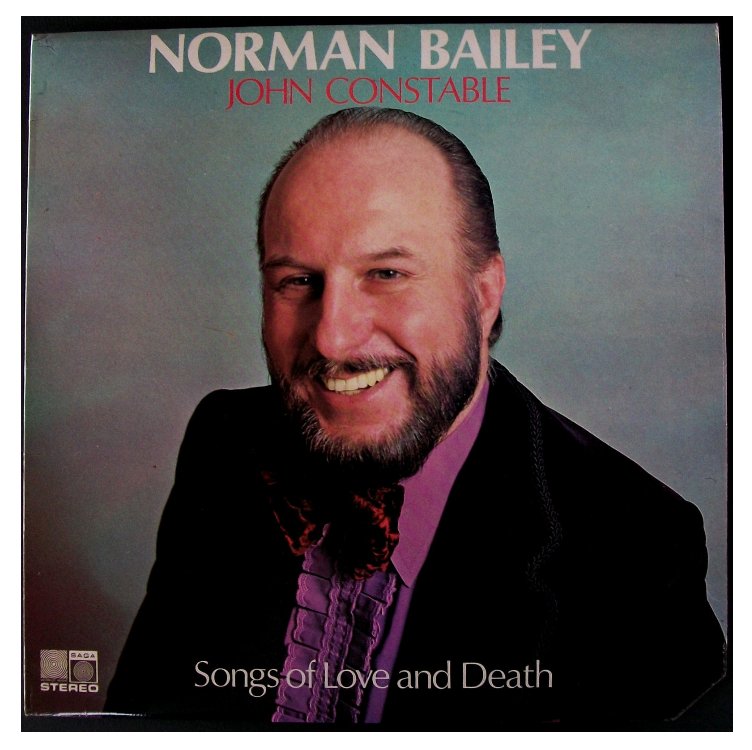

and then you rely on it and let it run itself? NB: I don’t do as many concerts as I used to.

At one time I used to do a lot of recitals, but I had to be very, very specific

with the time period to do a concert tour. I would then do a series

of about ten concerts, but as the years went by I found it very difficult

then to change vocally from doing opera – particularly

demanding Wagnerian roles – and then shifting over

to do lieder or English songs.

In arts songs generally the control and the presentation is completely different.

So if you’ve just got one concert, then it’s very, very difficult to leave

off a series of heavier operatic roles and spend two weeks preparing for the

one concert and doing the one concert.

NB: I don’t do as many concerts as I used to.

At one time I used to do a lot of recitals, but I had to be very, very specific

with the time period to do a concert tour. I would then do a series

of about ten concerts, but as the years went by I found it very difficult

then to change vocally from doing opera – particularly

demanding Wagnerian roles – and then shifting over

to do lieder or English songs.

In arts songs generally the control and the presentation is completely different.

So if you’ve just got one concert, then it’s very, very difficult to leave

off a series of heavier operatic roles and spend two weeks preparing for the

one concert and doing the one concert. BD: Is it only in the singer’s mind or is it also

in the audience’s mind?

BD: Is it only in the singer’s mind or is it also

in the audience’s mind?

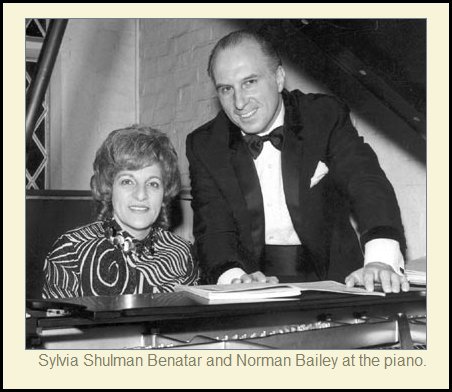

© 1994 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at Bailey’s apartment in Chicago on February 17, 1994. Portions were broadcast on WNIB three months later, and again in 1998. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2014. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.