San Francisco Opera: Revival Of Reimann's

'Lear'

SAN FRANCISCO — "Lear" is not a hot ticket these days at the War Memorial

Opera House.

Aribert Reimann's stark, provocative, uncompromising adaptation of the Shakespeare play does not offer local fans an opportunity to encounter a beloved diva bathing in verismo gush. For that the devout must go to "Adriana Lecouvreur" with Mirella Freni, which opened the season last week.

Nor does the modern Germanic tragedy offer canary fanciers a chance to adulate a gurgling diva in an ornate vocal circus. For that the laryngeal fetishists must go to "Orlando" with Marilyn Horne, which opens tonight.

Anyone interested in the prospect of opera as modern musical theater, however, must not miss "Lear." It is a gripping, ambitious, appropriately perplexing work, and San Francisco performs it brilliantly.

The opera isn't exactly new. Munich introduced it in 1978, with Dietrich

Fischer-Dieskau in the title role and Jean-Pierre Ponnelle in charge of

the staging. Kurt Herbert

Adler brought the same inventive production, with Thomas Stewart as

Lear, to San Francisco in 1981. It was one of the beleaguered impresario's

last hurrahs, and one of his finest hours.

The opera isn't exactly new. Munich introduced it in 1978, with Dietrich

Fischer-Dieskau in the title role and Jean-Pierre Ponnelle in charge of

the staging. Kurt Herbert

Adler brought the same inventive production, with Thomas Stewart as

Lear, to San Francisco in 1981. It was one of the beleaguered impresario's

last hurrahs, and one of his finest hours.

Now, "Lear" has returned. Familiarity is breeding fascination, and admiration.

Reimann, who has rushed in where both Verdi and Britten feared to tread, still grates and shocks. The listener is still overwhelmed by sonic booms, still assaulted by a multifaceted barrage of tone clusters, still unnerved by clashing layers of percussive rumble, still alarmed by screeching dissonances, rhythmic contradictions and contrapuntal disorder.

But the dramatic method behind the musical madness becomes more lucid and more logical with each exposure. The poignance of the lyric contrasts becomes more compelling.

Most illuminating, perhaps, is the growing awareness of Reimann's old-fashioned operatic instincts. In the final analysis, this "Lear" may sing and speak and shriek and croon in obvious modern accents. The basic language of the opera, however, remains stubbornly, accessibly conservative.

The text--Desmond Clayton's English translation of Claus H. Henneberg's simplified German translation of the original English--is still the thing. The vocal lines convey vibrant emotion, define character and project the action forward. The climactic stress and psychological revelations emanate from the singers.

For all its flamboyance, the massive orchestra still sets the scenes, punctuates the climaxes, reinforces the moods and adds subtle narrative comments. The separation of power between stage and pit endures.

Ponnelle's daring production--a fusion of Brechtian alienation, Noh-play ritual, epic formality and bloody realism--defines the inherent tones perfectly. A platform on the open stage, adorned with a few weeds and rocks, represents a timeless, mythic "blasted heath." As the crises of the drama unfold, the platform splits, rises and falls in various abstract configurations.

The shear theatricality of the concept is heightened marvelously by Pet Halmen's brash, symbol-laden costumes and by Thomas J. Munn's sometimes subtle, sometimes glaring lighting effects.

The current cast, only slightly different from that of 1981, performs with awesome intensity. Stewart may not command Fischer-Dieskau's scale of vocal color, but he dominates the proceedings in his own masterful way. He traces the decline of the noble King with heroic pathos and meets all vocal challenges with unflagging skill and vigor.

The fundamental distinctions of the three daughters are illuminated by Helga Dernesch as the flamboyantly erotic Goneril, Anja Silja as the hysterically cackling Regan and Sheri Greenawald as the serene, almost ethereal Cordelia.

David Knutson, incredibly vulnerable and boyish as Edgar, manages the countertenor flights of Poor Tom with otherworldly sweetness. Jacque Trussel provides the perfect counterforce as an Edmund consumed to the breaking point with strident passions.

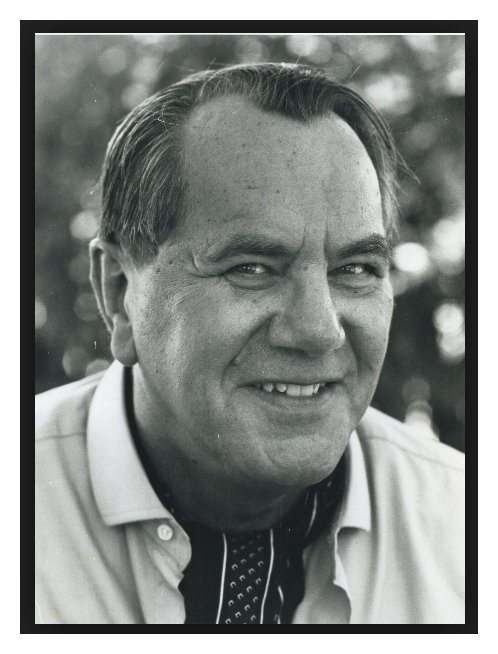

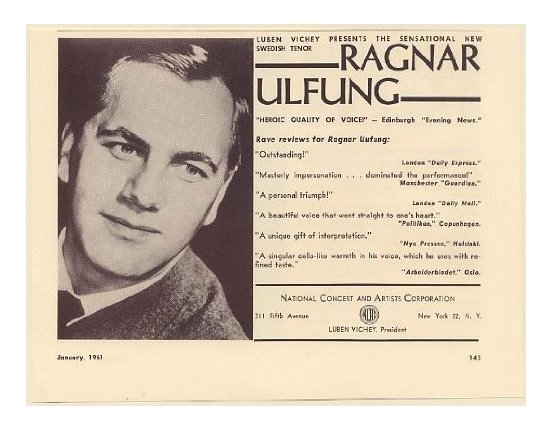

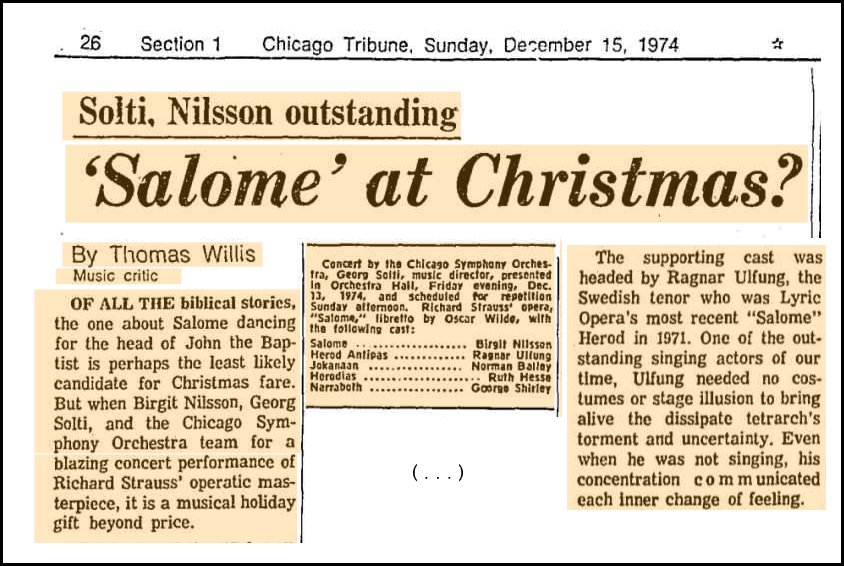

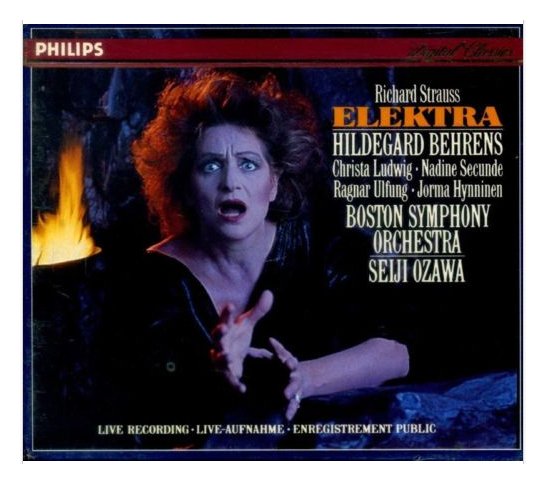

Robert Langdon-Lloyd projects the knowing dementia and the pointed Sprechgesang of the Fool with muted precision. Ragnar Ulfung offers a sympathetic Kent, Chester Ludgin a stalwart Gloucester, Timothy Noble and John Duykers a blustery pair of duped Dukes (Albany and Cornwall).

Friedemann Layer, the young Viennese maestro who has inherited the baton from the injured Gerd Albrecht, conducts with an ideal combination of dedication, indulgence and control.

The house wasn't full Thursday night. Nevertheless, the ovation at the end bordered on the cataclysmic. There may be hope.

RU

RU RU

RU

RU

RU BD

BD

RU

RU