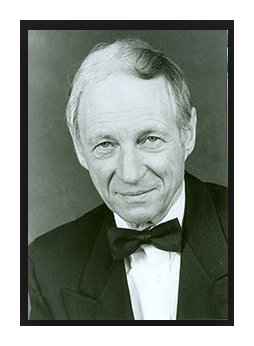

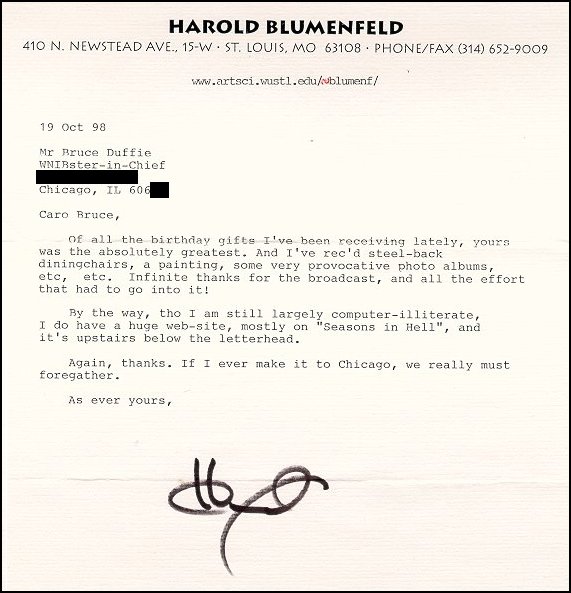

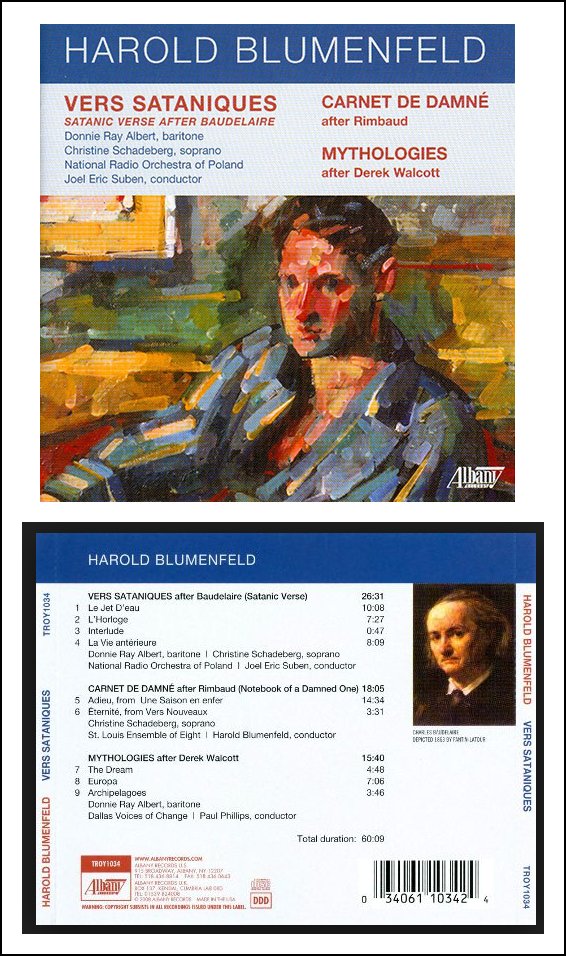

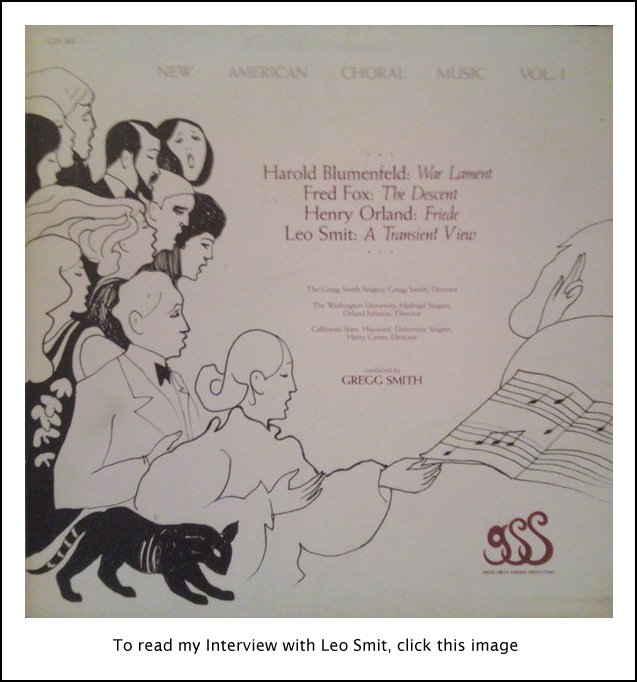

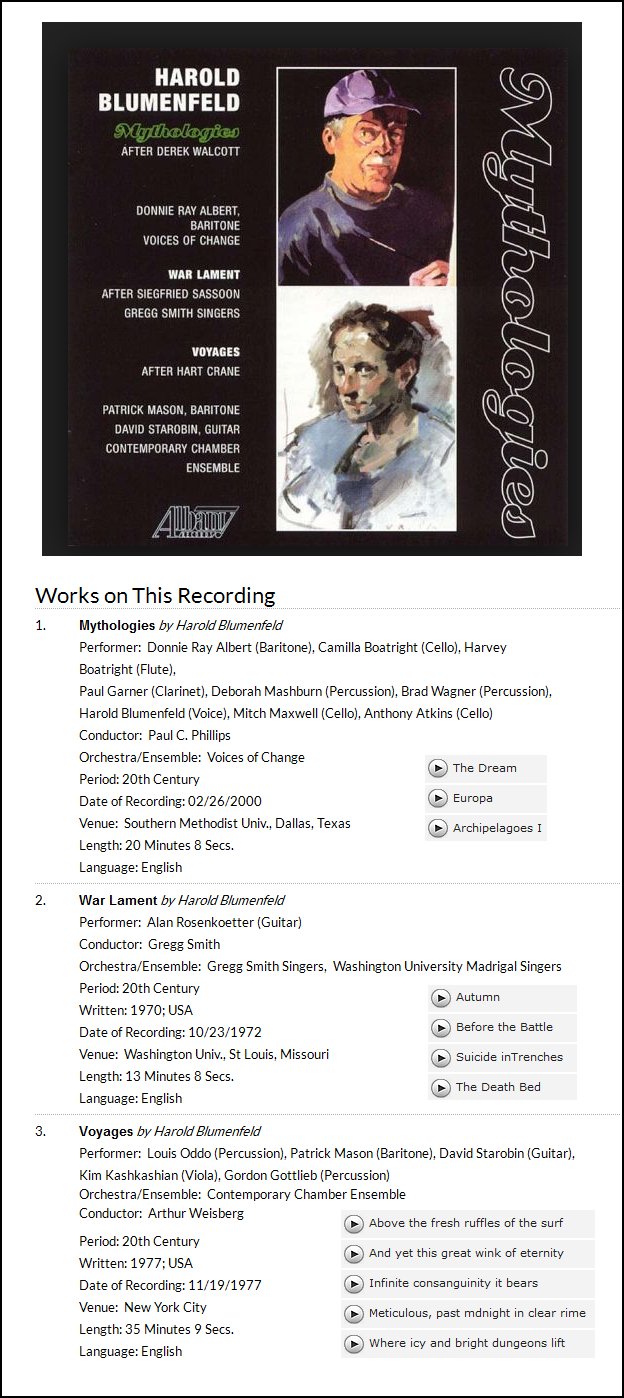

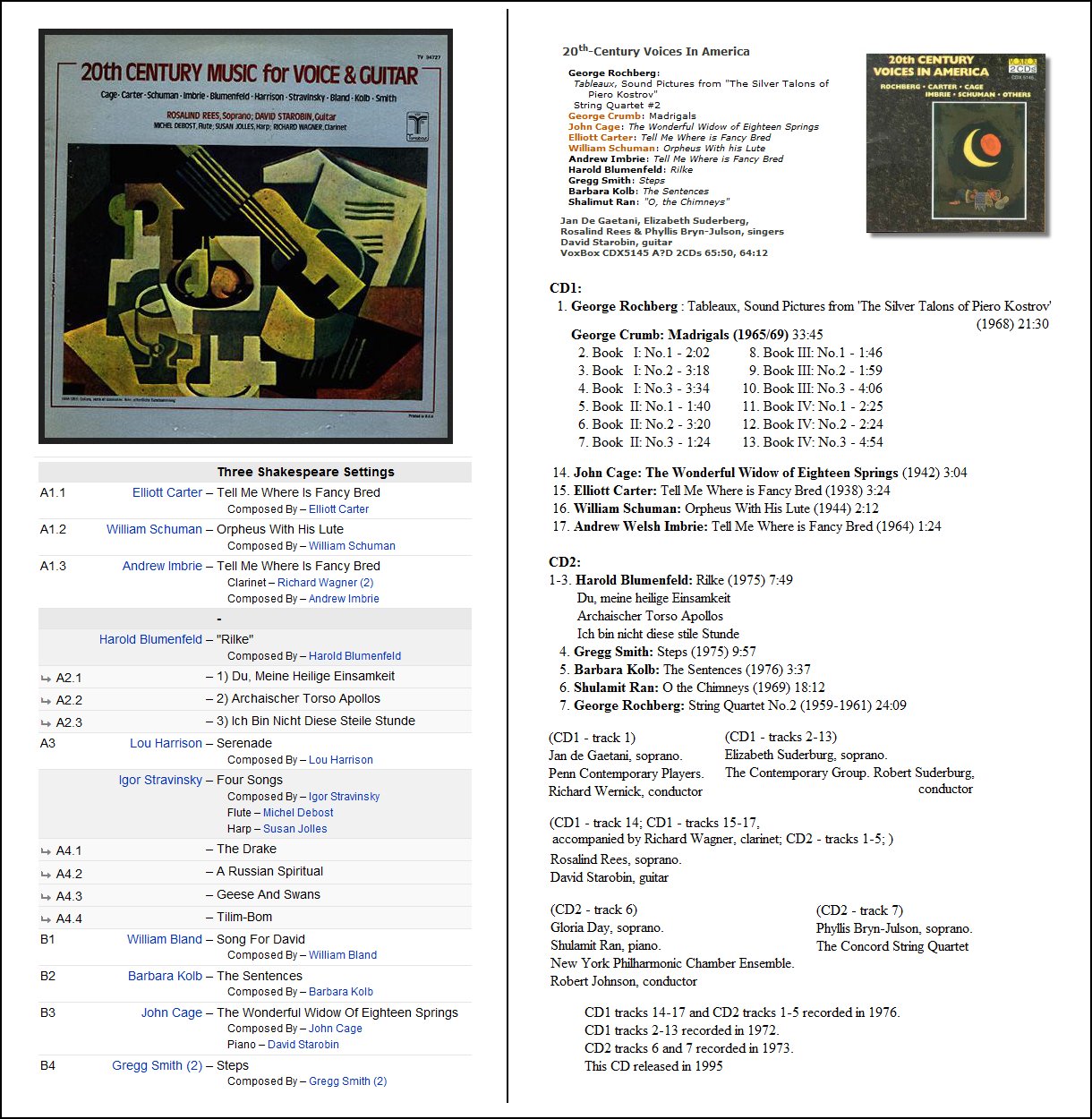

Harold Blumenfeld, professor emeritus of music in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, died Saturday, Nov. 1, 2014, from complications of Alzheimer’s disease. He was 91. Born Oct. 15, 1923, in Seattle, Blumenfeld studied at the Eastman School of Music from 1941-43. During World War II, he served as an interpreter in the U.S. Army Signal Corp, and was present at the liberation of Ohrdruf, the first Nazi concentration camp liberated by U.S. troops. Blumenfeld remained in Europe after the war, deploying his language skills to help identify former members of the Nazi Party. He then resumed his studies at the University of Zurich and at Yale University, earning both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree from Yale, in 1948 and ’49 respectively. Over the next four summers, he trained as a conductor with Robert Shaw, Leonard Bernstein, and Boris Goldovsky at Tanglewood, summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. In 1950, Blumenfeld joined the faculty of Washington University, where he taught until his retirement in 1989. From 1960-71, he directed the Washington University Opera Studio and, from 1962-66, also directed Opera Theatre of St. Louis. An active music critic, he regularly wrote for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Opera News and other publications. Blumenfeld’s own compositions include “Fourscore: An Opera of Opposites” (1986) and “Breakfast Waltzes” (1991), both with librettist Charles Kondek, as well as vocal settings of works by Harold Hart Crane, Derek Walcott, Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, Rainer Maria Rilke and Osip Mandelstam. Blumenfeld was the first composer to devote extensive attention to the poetry of Arthur Rimbaud, beginning with a setting of “Being Beauteous” (c. 1980) and culminating in the two-act opera “Seasons in Hell” (1996), which traces Rimbaud’s adolescent adventures and disastrous fortune-seeking in Africa. [CD cover and information are shown in the next box below.] In 2001, Blumenfeld and Kondek completed “Borgia Infami,” an opera based on the notorious Renaissance family. In 2007, Blumenfeld recorded “Vers Sataniques,” based on Baudelaire’s “Flowers of Evil,” with the National Radio Orchestra of Poland. -- From the website of

Washington University in St. Louis (with an addition and

correction)

-- Names which are links on this webpage refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

Bruce Duffie:

Let’s start with a really easy

question. Where’s opera going today?

Bruce Duffie:

Let’s start with a really easy

question. Where’s opera going today? BD:

Was the audience receptive to all of these works?

BD:

Was the audience receptive to all of these works? BD: What about an

overly-familiar work like Bohème

or Traviata?

BD: What about an

overly-familiar work like Bohème

or Traviata? HB: [Laughs]

Sing it, and conduct it, or stage it, and then try to resist the

temptation to compose an opera. It’s insane.

HB: [Laughs]

Sing it, and conduct it, or stage it, and then try to resist the

temptation to compose an opera. It’s insane. Roman Osipovich Jakobson (Russian: Рома́н

О́сипович Якобсо́н; October 11, 1896 – July 18, 1982) was a

Russian–American linguist and literary theorist. Roman Osipovich Jakobson (Russian: Рома́н

О́сипович Якобсо́н; October 11, 1896 – July 18, 1982) was a

Russian–American linguist and literary theorist.As a pioneer of the structural analysis of language, which became the dominant trend in linguistics during the first half of the 20th century, Jakobson was among the most influential linguists of the century. Influenced by the work of Ferdinand de Saussure, Jakobson developed, with Nikolai Trubetzkoy, techniques for the analysis of sound systems in languages, inaugurating the discipline of phonology. He went on to apply the same techniques of analysis to syntax and morphology, and controversially proposed that they be extended to semantics (the study of meaning in language). He made numerous contributions to Slavic linguistics, most notably two studies of Russian case and an analysis of the categories of the Russian verb. Drawing on insights from Charles Sanders Peirce's semiotics, as well as from communication theory and cybernetics, he proposed methods for the investigation of poetry, music, the visual arts, and cinema. Through his decisive influence on Claude Lévi-Strauss and Roland Barthes, among others, Jakobson became a pivotal figure in the adaptation of structural analysis to disciplines beyond linguistics, including philosophy, anthropology, and literary theory; this generalization of Saussurean methods, known as "structuralism", became a major post-war intellectual movement in Europe and the United States. |

BD: Must he make

sure he puts back more than he takes

away?

BD: Must he make

sure he puts back more than he takes

away? HB:

The piece is little over ten

years old now, and I don’t remember exactly why I chose those, although

I can tell you something about it. Some years ago, I read Voyages of Hart Crane, and I

thought that there was

really something there that I had to grow up to. Then, ten years

later, I read them again, and felt, “Oh, my God,

this is

something I have to do. I have to try to set this cycle to music,

because I hear some resonances in this poetry that I want

to capture in terms of musical sound.”

Marvelous as the

language is, one sometimes is a little mystified as to its

meaning. Then, once I thought that I had captured certain

meanings under Crane, I wanted to capture them in music. So I

went ahead

and set that at Yaddo about twelve

years ago. I remember to some extent I

used the viola as the voice of the lover. Voyages is a cycle which depicts

the rise, flowering, and

final decay of a very wild love affair, and so the viola was the

voice of the lover, in a sense, in one of these middle voyages. [On the recording, shown at right, the

violist is Kim

Kashkashian.] The piece goes on for forty

minutes. On the disc we have the first twenty minutes of

it. The last two parts aren’t included. This was

done as part of an American Academy Institute of Arts and Letters

Award. I had one side and

George Perle had

the other side, so I had to select twenty-five

minutes. I think I should have chosen parts 2 and 3, rather than

parts 1 and 2. For a

section of that length, it would have been better to go with the poems

3, 5 and 6,

rather than 1, 2 and 3. But it’s no problem. It’s okay as

it is. It’s a little

complicated... there are actually five poems set. A couple

are combined into one poem. The last poems of the Voyages series are so

incandescent and so transformed, where Venus

arises out of the sea on her half shell, and symbolizes the

immutable beauty of the world, which takes the

place of love.

HB:

The piece is little over ten

years old now, and I don’t remember exactly why I chose those, although

I can tell you something about it. Some years ago, I read Voyages of Hart Crane, and I

thought that there was

really something there that I had to grow up to. Then, ten years

later, I read them again, and felt, “Oh, my God,

this is

something I have to do. I have to try to set this cycle to music,

because I hear some resonances in this poetry that I want

to capture in terms of musical sound.”

Marvelous as the

language is, one sometimes is a little mystified as to its

meaning. Then, once I thought that I had captured certain

meanings under Crane, I wanted to capture them in music. So I

went ahead

and set that at Yaddo about twelve

years ago. I remember to some extent I

used the viola as the voice of the lover. Voyages is a cycle which depicts

the rise, flowering, and

final decay of a very wild love affair, and so the viola was the

voice of the lover, in a sense, in one of these middle voyages. [On the recording, shown at right, the

violist is Kim

Kashkashian.] The piece goes on for forty

minutes. On the disc we have the first twenty minutes of

it. The last two parts aren’t included. This was

done as part of an American Academy Institute of Arts and Letters

Award. I had one side and

George Perle had

the other side, so I had to select twenty-five

minutes. I think I should have chosen parts 2 and 3, rather than

parts 1 and 2. For a

section of that length, it would have been better to go with the poems

3, 5 and 6,

rather than 1, 2 and 3. But it’s no problem. It’s okay as

it is. It’s a little

complicated... there are actually five poems set. A couple

are combined into one poem. The last poems of the Voyages series are so

incandescent and so transformed, where Venus

arises out of the sea on her half shell, and symbolizes the

immutable beauty of the world, which takes the

place of love.  BD:

When you get a commission, how do you decide

if you’ll accept it or turn it down?

BD:

When you get a commission, how do you decide

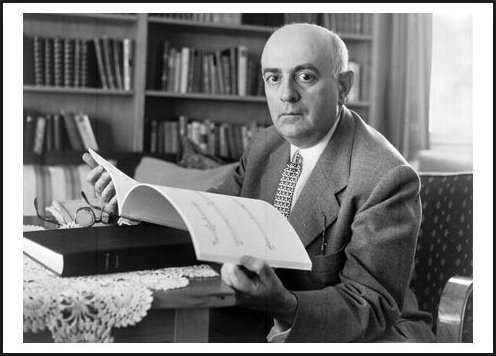

if you’ll accept it or turn it down?Theodor W. Adorno; born Theodor

Ludwig Wiesengrund; September 11, 1903 – August 6, 1969 was a German

philosopher, sociologist, and composer known for his critical theory of

society. He was a leading member of the Frankfurt School of

critical theory, whose work has come to be associated with thinkers

such as Ernst Bloch, Walter Benjamin, Max Horkheimer and Herbert

Marcuse, for whom the work of Freud, Marx, and Hegel were essential to

a critique of modern society. He is widely regarded as one of the 20th

century's foremost thinkers on aesthetics and philosophy, as well as

one of its preeminent essayists. As a critic of both fascism and what

he called the culture industry, his writings—such as Dialectic of

Enlightenment (1947), Minima Moralia (1951) and Negative Dialectics

(1966)—strongly influenced the European New Left. He was a leading member of the Frankfurt School of

critical theory, whose work has come to be associated with thinkers

such as Ernst Bloch, Walter Benjamin, Max Horkheimer and Herbert

Marcuse, for whom the work of Freud, Marx, and Hegel were essential to

a critique of modern society. He is widely regarded as one of the 20th

century's foremost thinkers on aesthetics and philosophy, as well as

one of its preeminent essayists. As a critic of both fascism and what

he called the culture industry, his writings—such as Dialectic of

Enlightenment (1947), Minima Moralia (1951) and Negative Dialectics

(1966)—strongly influenced the European New Left.Amidst the vogue enjoyed by existentialism and positivism in early 20th-century Europe, Adorno advanced a dialectical conception of natural history that critiqued the twin temptations of ontology and empiricism through studies of Kierkegaard and Husserl. As a classically trained pianist whose sympathies with the twelve-tone technique of Arnold Schoenberg resulted in his studying composition with Alban Berg of the Second Viennese School, Adorno's commitment to avant-garde music formed the backdrop of his subsequent writings and led to his collaboration with Thomas Mann on the latter's novel Doctor Faustus, while the two men lived in California as exiles during the Second World War. Working for the newly relocated Institute for Social Research, Adorno collaborated on influential studies of authoritarianism, antisemitism and propaganda that would later serve as models for sociological studies the Institute carried out in post-war Germany. Upon his return to Frankfurt, Adorno was involved with the reconstitution of German intellectual life through debates with Karl Popper on the limitations of positivist science, critiques of Heidegger's language of authenticity, writings on German responsibility for the Holocaust, and continued interventions into matters of public policy. As a writer of polemics in the tradition of Nietzsche and Karl Kraus, Adorno delivered scathing critiques of contemporary Western culture. Adorno's posthumously published Aesthetic Theory, which he planned to dedicate to Samuel Beckett, is the culmination of a lifelong commitment to modern art which attempts to revoke the "fatal separation" of feeling and understanding long demanded by the history of philosophy and explode the privilege aesthetics accords to content over form and contemplation over immersion. |

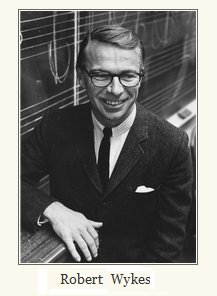

Robert

A. Wykes (born May 19, 1926 in Aliquippa, Pennsylvania) is an American

composer of contemporary classical music and flautist. Robert

A. Wykes (born May 19, 1926 in Aliquippa, Pennsylvania) is an American

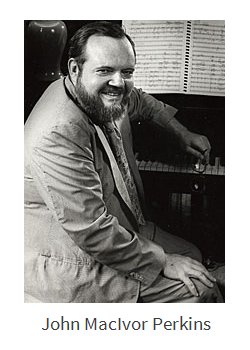

composer of contemporary classical music and flautist.He began studying the flute as a child, then served in World War II. He then attended the Eastman School of Music, obtaining a master's degree in music theory. He taught at Bowling Green State University from 1950 to 1952, also playing flute with the Toledo Symphony. His opera The Prankster premiered at the University in January 1952. Later that year, Wykes left Bowling Green to study and teach at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign where he stayed until he graduated with a doctorate in music in 1955. He was appointed to the music faculty of Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri in 1955, becoming a full professor in 1965. He played flute with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra from 1963 to 1967 and with the Studio for New Music from 1966 to 1969. He retired from Washington University in 1988. He was appointed composer-in-residence at the Djerassi Foundation in Woodside, California in 1989 and was a visiting scholar at the Computer Center for Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) at Stanford University in 1991. His notable students include Olly Wilson. Wykes's orchestral works have been performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Minnesota Orchestra, the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra, the National Orchestra of Brazil and the Pro Arte Symphony of Brazil, and the Denver Symphony.  John MacIvor Perkins (Born Aug. 2, 1935, in St. Louis, died Nov 12, 2010) Perkins graduated from John Burroughs School in 1953 and in 1958 earned both a bachelor of arts degree from Harvard University and a bachelor of music degree from the New England Conservatory of Music.  In

1962, Perkins earned a master of fine arts degree from Brandeis

University. He spent several years on faculty at the University of

Chicago, but, in 1965, he returned to Harvard, where he taught for the

next five years. In

1962, Perkins earned a master of fine arts degree from Brandeis

University. He spent several years on faculty at the University of

Chicago, but, in 1965, he returned to Harvard, where he taught for the

next five years.Perkins came to Washington University in 1970 as an associate professor of music, and he also served as chair of music until 1976. His scholarly interests ranged from 20th-century serial music and rhythmic notation to the works of composers Igor Stravinsky, Anton Webern and Luigi Dallapiccola. Perkin’s own compositions include approximately three dozen works, ranging from one-act operas and songs for voice and piano to various compositions for orchestra, chorus, chamber groups and solo piano. His numerous honors included a Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship and the American Academy and National Institute of Arts and Letters Award as well as commissions from Harvard’s Fromm Music Foundation, the New Music Circle of St. Louis, concert pianist Easley Blackwood and the Smithsonian Institution, among others. Perkins retired in 2001, though he continued to teach composition and counterpoint tutorials. To mark his retirement, the Department of Music hosted a concert “Celebrating the Music of John MacIvor Perkins” in Edison Theatre. More recently, the Washington University Symphony Orchestra premiered a new work by Perkins, After and Before, as part of its 2004 Chancellor’s Concert. [More information about this concert is in the box below.] -Liam Otten  Roland Carroll Jordan, Jr. (born

1938) is an American composer and music theorist. He studied in Texas

and Pennsylvania before receiving his Ph.D. from Washington University

in St. Louis, where he taught theory and composition for three decades.

As a composer, Jordan has written for both large ensembles and chamber

groups, and as a music theorist, he has explored the uses of

phenomenological methodology and structuralist/post-structuralist

theory.

|

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on July 16, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB three months later, and again in 1993 and 1998. This transcription was made in 2016, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.