This box contains a biography of the tenor taken (and slightly edited) from the Bach Cantatas website, followed by an obituary published in The Guardian (of London), which also reflects some opinions of the author, Alan Blyth.

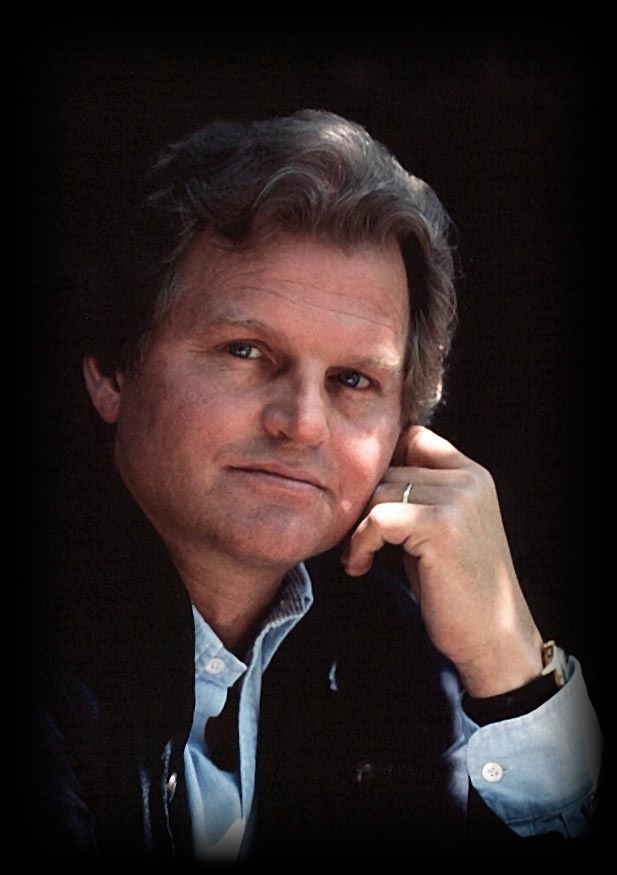

* * * * * Obituary by Alan Blyth in The Guardian Gösta Winbergh, who has died at the age of 58,

was one of the most admired tenors of recent times. He made his

name in Mozart, then progressed over the past 10 years to heavier

roles, which he served with the same distinction. His warm and attractive

timbre was used in the most artistic way, signifying his considerable

intelligence.

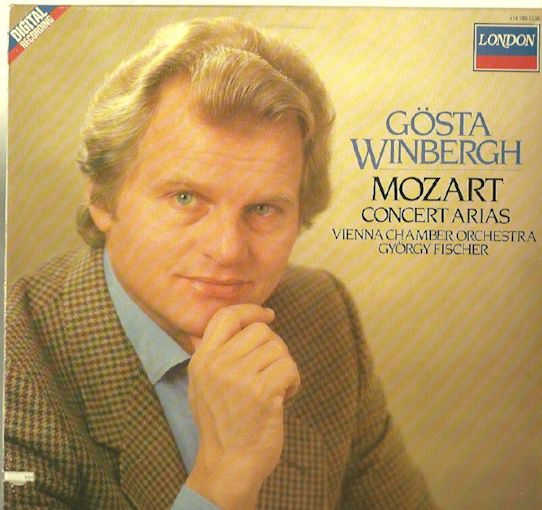

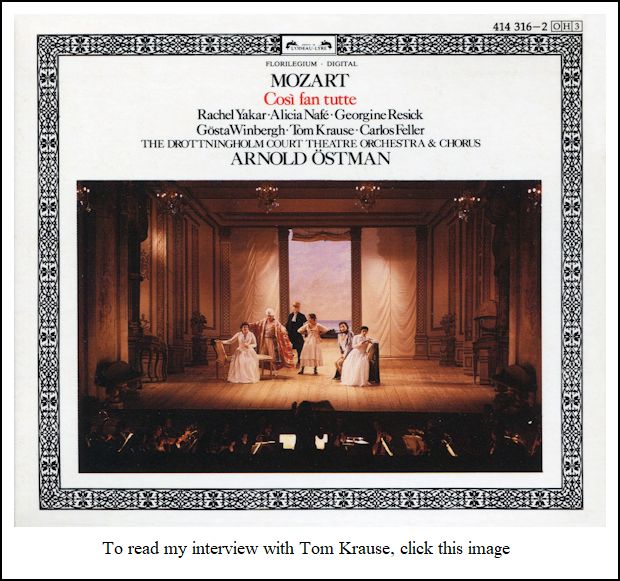

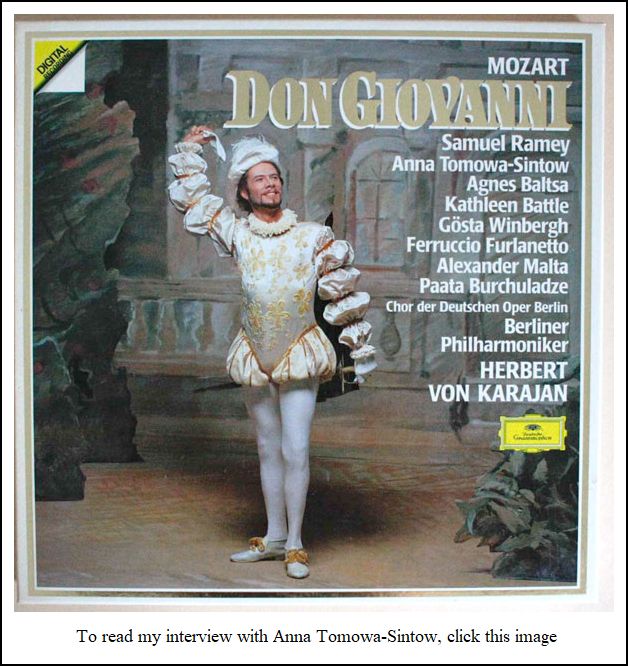

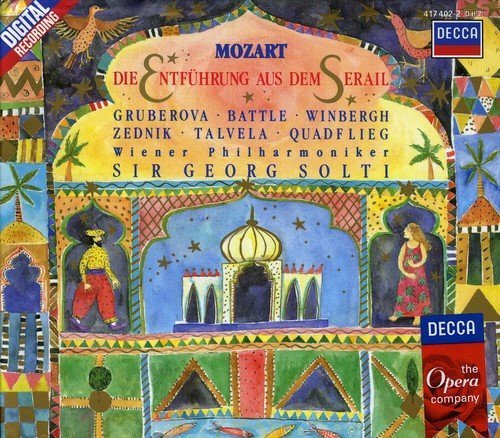

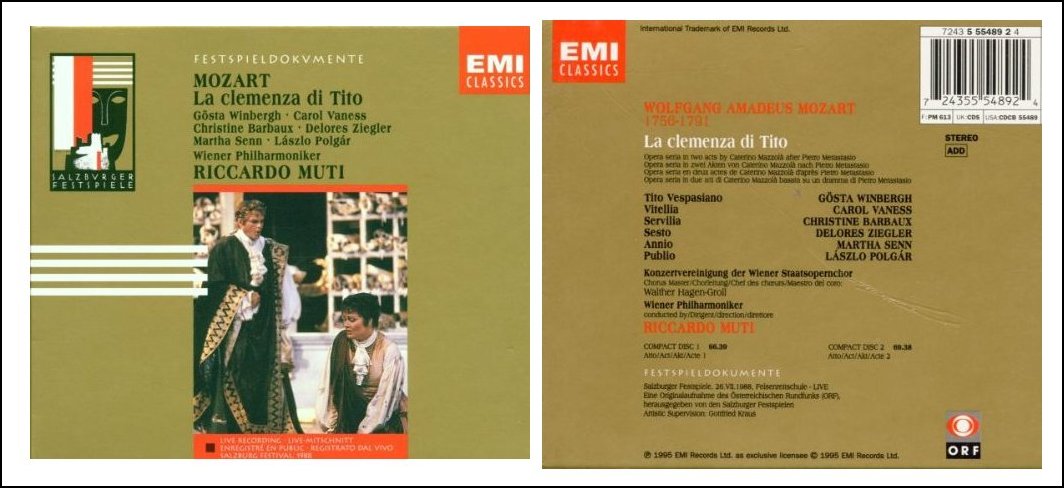

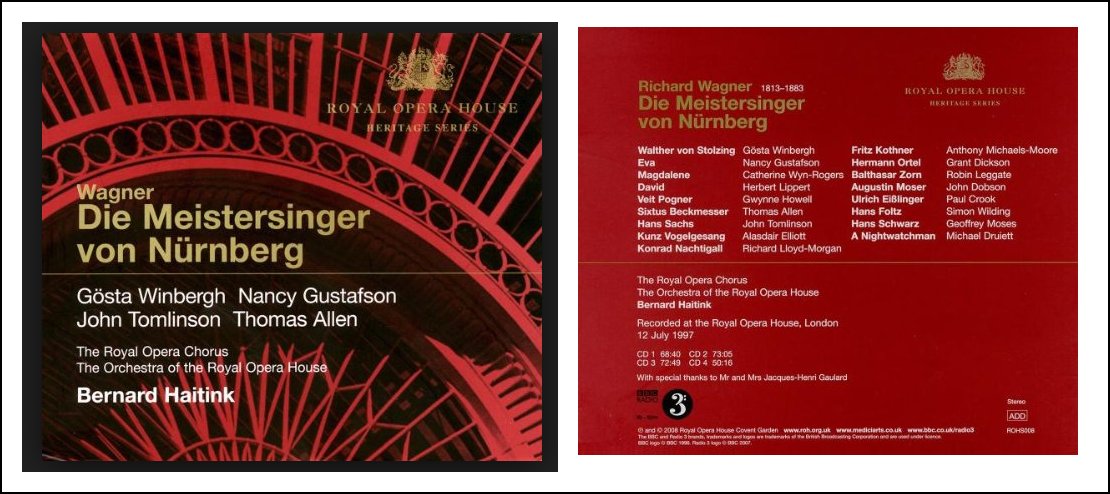

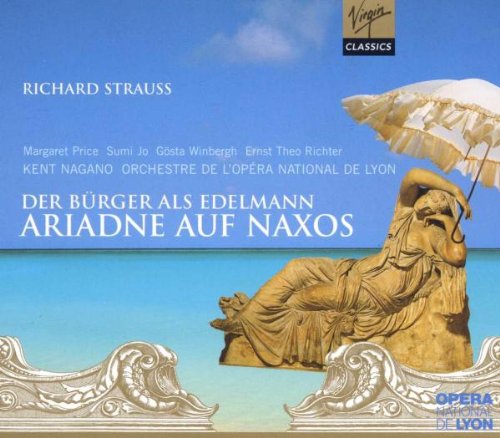

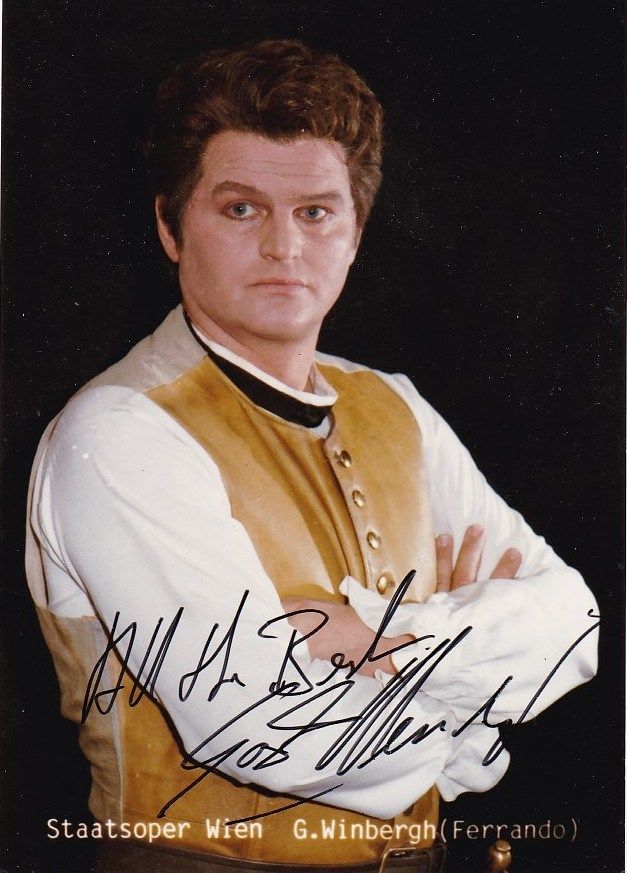

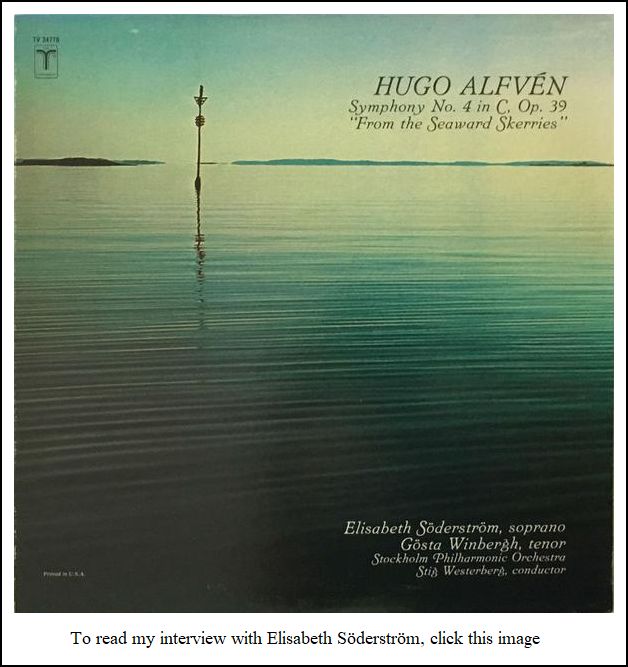

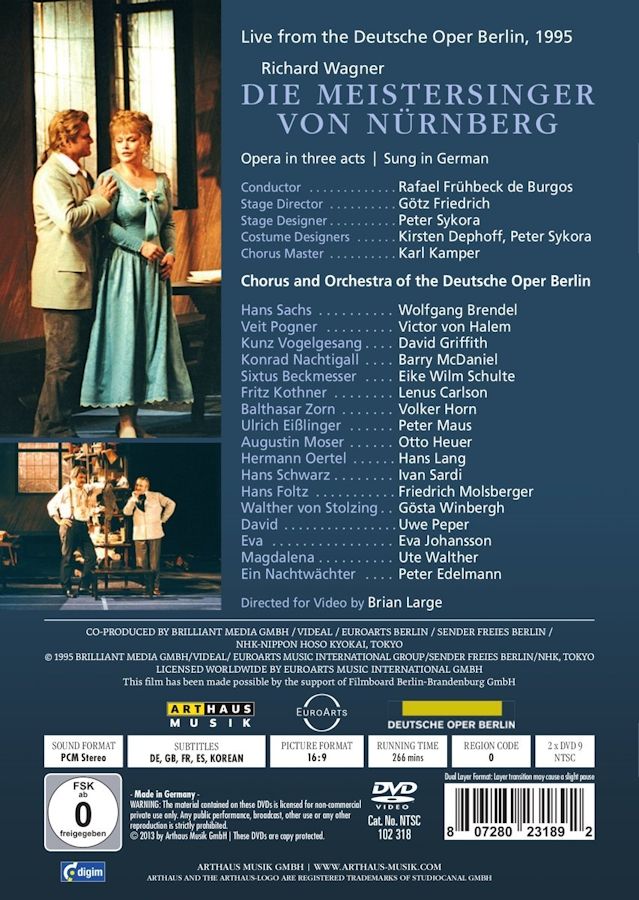

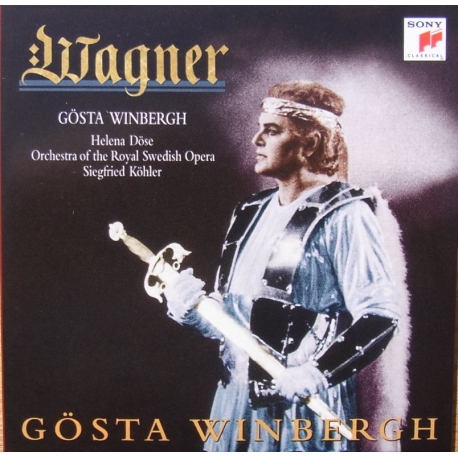

Covent Garden utilised him first in 1991 as a manly and authoritative Emperor Titus in Mozart's La Clemenza Di Tito, a role he made very much his own. He returned, first as Mozart's Mitridate, and then in his new guise as a Wagnerian to sing a handsome - vocally and dramatically - and lyrical Lohengrin (a role he had first sung in Zurich in an avant-garde staging in 1991), which brought him critical and public praise. He followed that with an even more impressive Walther in Die Meistersinger (1993). Usually tenors find this among the most taxing of parts, but Winbergh delivered it with such ease and musicality that one wondered why others have found it so difficult. A bonus to Winbergh's excellent singing was his stage deportment. He actually looked right for both these parts, conveying a deal of romantic ardour. Most recently he had tackled Tristan and Parsifal, though, sadly, not for British audiences. Also among his latter-day successes were the Emperor in Richard Strauss's Die Frau Ohne Schatten and Florestan in Beethoven's Fidelio (it was the day after performing that role at the Vienna State Opera that he suffered his fatal heart attack). Recently he recorded the part for the budget label Naxos, but there was nothing "budget" about his performance: his ringing tones and his remarkable execution of the final section of his big act two scene were truly astonishing in a part that is a nemesis for so many tenors. Winbergh might never have become a singer, as he trained as a structural engineer before enrolling at the Royal Academy in his native Stockholm, studying with the famous baritone Erik Saeden. His 1972 debut at Göteborg as Rodolfo immediately attracted the attention of the Royal Opera in Stockholm, where he was engaged as principal tenor, remaining a member of the ensemble until 1981. However, he was soon in demand abroad, mostly for his Mozartian roles. He was engaged as early as 1980 by Glyndebourne, where he sang a mellifluous Belmonte in Die Entführung. His first appearance at the Metropolitan in 1983 was as Don Ottavio, and at La Scala in 1985 as Tamino; he returned there for Idomeneo in 1990. He was a regular visitor to the Salzburg Festival, where he was a notable Ferrando in Così Fan Tutte. Even in those years Winbergh was not confined to Mozart. His repertory included, among others, Count Almaviva, Nemorino, the Duke of Mantua, Alfredo, Lensky and Faust, all of which benefited from his sweet, refined singing and alert acting. The earlier part of Winbergh's career is preserved on CD in his charming account of Ernesto in Don Pasquale, his Don Ottavio for Karajan, Tito for Muti, Belmonte for Solti, and Ferrando for Arnold Östmann in a performance at Drottningholm, where he had appeared in the part on stage. Even more important is a recent issue on DVD of his Walther in a fine Berlin performance of Die Meistersinger. In every respect it captures the essence of his skills in the role, both vocal and dramatic. He is survived by his wife, a son and a daughter. ·Gösta Winbergh, tenor, born December 30 1943;

died March 18 2002. |

||||||||||||

Gösta Winbergh at Lyric

Opera of Chicago

1982 - Così fan tutte (Ferrando) with

Yakar, Howells,

Stilwell,

Hynes, Trimarchi; Rudel, Sciutti, Griffin,

Schuler

1988-89 - Don Giovanni (Don Ottavio) with Ramey, Vaness, Mattila, Desderi, McLaughlin, Macurdy; Bychkov, Ponnelle/Lata, Schuler 1989-90 - Clemenza di Tito (Tito) with Vaness, Troyanos/Mentzer, Graham, Doss; Davis, Rochaix, Toffolutti, Sullivan 1998-99 - Meistersinger (Walther) with Rootering, Gustafson, Pape, Schulte, Schade, Redmon, Del Carlo; Thielemann, Horres, Reinhardt, Schuler 2001-02 - Parsifal (Parsifal) [Final performance on March 9, 2002] with Salminen, Malfitano, Delavan, Kristansson; Davis, Lehnhoff, Bauer, Schuler |

GW: The secret of singing Mozart! It’s work,

hard work!

GW: The secret of singing Mozart! It’s work,

hard work!  BD: Do you do any of the lesser-known ones, like

La Finta Semplice?

BD: Do you do any of the lesser-known ones, like

La Finta Semplice? BD: Do you like these characters that you sing?

BD: Do you like these characters that you sing?

BD: You try to put more strength into the role?

BD: You try to put more strength into the role?

GW: He’s a young man who’s met this Konstanze before.

He’s heard that she’s sitting as a prisoner on this little

island. He’s a very warm and innocent person, because his love

is steering him all the time. Without Pedrillo he would never

do it. He would never have been strong enough to go and

make up all these stories to get Konstanze. Osmin would have kicked

him away long ago. He’s one of those weak characters of Mozart

— like Don Ottavio — but I think

Pedrillo is the one who really sets everything up for him. Without

Pedrillo he would never have been able to find her, or make up the story

that he’s an architect. He does what Pedrillo says and goes along

with the plot, and it works out. I hadn’t really thought a lot

about Belmonte.

GW: He’s a young man who’s met this Konstanze before.

He’s heard that she’s sitting as a prisoner on this little

island. He’s a very warm and innocent person, because his love

is steering him all the time. Without Pedrillo he would never

do it. He would never have been strong enough to go and

make up all these stories to get Konstanze. Osmin would have kicked

him away long ago. He’s one of those weak characters of Mozart

— like Don Ottavio — but I think

Pedrillo is the one who really sets everything up for him. Without

Pedrillo he would never have been able to find her, or make up the story

that he’s an architect. He does what Pedrillo says and goes along

with the plot, and it works out. I hadn’t really thought a lot

about Belmonte.

BD: More so than other opera houses?

BD: More so than other opera houses?

GW: Yes. I work on them for a certain amount

of time, and then if I feel good, I go on with them. But if I

feel that it didn’t really work for me, I would drop it.

GW: Yes. I work on them for a certain amount

of time, and then if I feel good, I go on with them. But if I

feel that it didn’t really work for me, I would drop it.  BD: It’s just more singing?

BD: It’s just more singing?  GW: Not really. The way

I sing the part is the same in all houses. It is the acoustic in

each house which makes the voice grow larger or smaller. In

smaller houses it’s more difficult to sing dramatic parts because the

voice doesn’t carry; it doesn’t grow. In a big house, the

voice has time to grow and to develop. In small houses it just

bounces off the back wall, and doesn’t go anywhere. It’s very important

for me to sing in houses like the Met, and in here in Chicago, and San

Francisco. Munich and Vienna are also big houses, but not as big

as here in America. They also have different acoustics. If

you compare the acoustic in Vienna with the acoustic here in Chicago,

the acoustic is good here in Chicago, but in Vienna it’s Zauber,

it’s magic! The Metropolitan has a very good acoustic, and

even San Francisco. Now, after they rebuilt it, it has a fabulous

acoustic. Some houses are so dry, and it gets worse and worse sometimes

when it is rebuilt. I was in San Francisco last year, and it was

a really, really nice acoustic. It’s important for us to feel that

the voice responds when you’re on the stage, that it comes back. Sometimes

you feel that it goes, and you just stand in a closet and sing, which is

hard.

GW: Not really. The way

I sing the part is the same in all houses. It is the acoustic in

each house which makes the voice grow larger or smaller. In

smaller houses it’s more difficult to sing dramatic parts because the

voice doesn’t carry; it doesn’t grow. In a big house, the

voice has time to grow and to develop. In small houses it just

bounces off the back wall, and doesn’t go anywhere. It’s very important

for me to sing in houses like the Met, and in here in Chicago, and San

Francisco. Munich and Vienna are also big houses, but not as big

as here in America. They also have different acoustics. If

you compare the acoustic in Vienna with the acoustic here in Chicago,

the acoustic is good here in Chicago, but in Vienna it’s Zauber,

it’s magic! The Metropolitan has a very good acoustic, and

even San Francisco. Now, after they rebuilt it, it has a fabulous

acoustic. Some houses are so dry, and it gets worse and worse sometimes

when it is rebuilt. I was in San Francisco last year, and it was

a really, really nice acoustic. It’s important for us to feel that

the voice responds when you’re on the stage, that it comes back. Sometimes

you feel that it goes, and you just stand in a closet and sing, which is

hard.  GW: Not all of them! You spoke

about Lohengrin. He’s not a real person, he’s some fantasy

figure.

GW: Not all of them! You spoke

about Lohengrin. He’s not a real person, he’s some fantasy

figure. BD: Do you have to be perfect

in them?

BD: Do you have to be perfect

in them? BD: Now you are here in Chicago singing Meistersinger,

so let me ask you a bit about Walther. Are he and Eva happy

in ‘Act Four’?

BD: Now you are here in Chicago singing Meistersinger,

so let me ask you a bit about Walther. Are he and Eva happy

in ‘Act Four’?  BD: So you’ve paced your career very well?

BD: So you’ve paced your career very well?

© 1982 & 1999 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in Chicago on November 3, 1982, and February 25, 1999. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1985, 1987, 1991 and in 1993. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website early in 2018. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

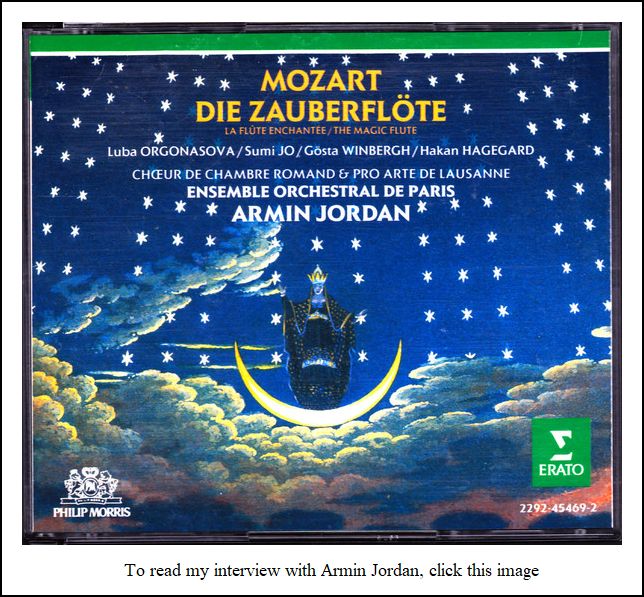

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.