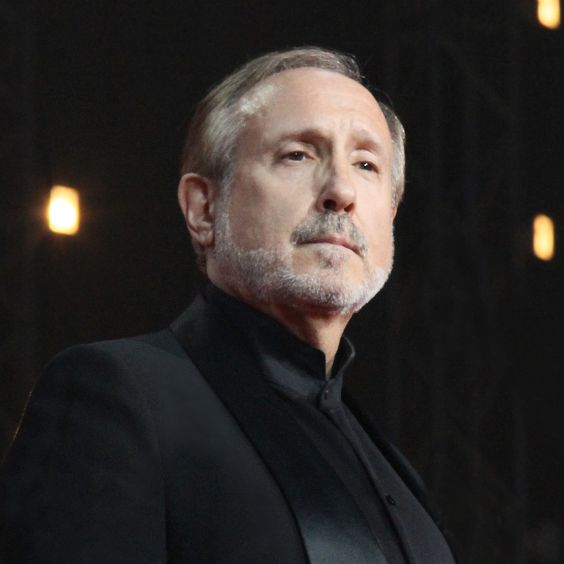

| Neil Shicoff (born June 2, 1949) is an American

Jewish opera singer and cantor known for his lyric tenor singing and his

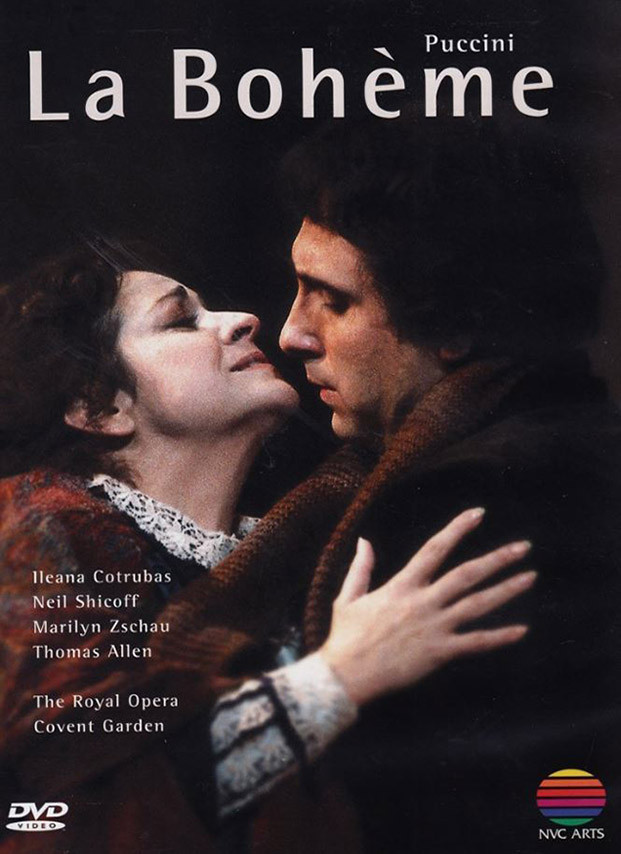

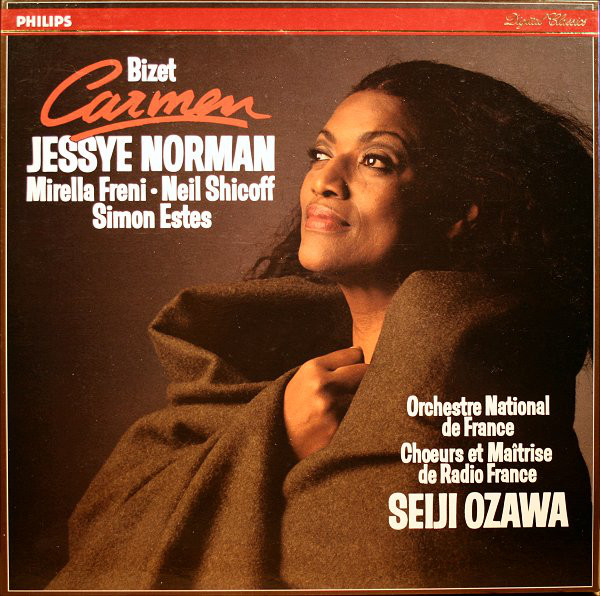

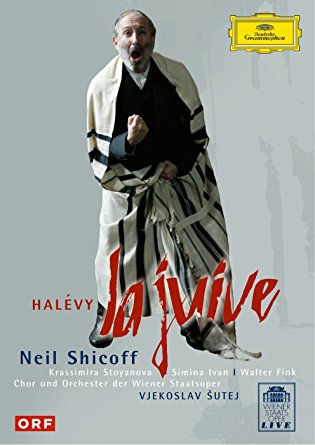

dramatic, emotional acting. He was born in Brooklyn, New York, and studied at the Juilliard School of Music, with his father, the hazzan Sidney Shicoff and others, including Franco Corelli in the early 1980s. He sang in small theaters in New York before music school, including a Don Jose in Bizet's Carmen at Amato Opera and small roles at Juilliard, and was an apprentice at the Santa Fe Opera in the summer of 1973. His professional debut as a tenor lead in a big opera house was in the title role in Verdi's Ernani, conducted by James Levine in Cincinnati in 1975. In 1976, Shicoff made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera as Rinuccio in Gianni Schicchi conducted by Levine. Shicoff was then engaged by the Met to sing the tenor leads in Rigoletto, La Bohème, Der Rosenkavalier, and Werther, which was to become one of his signature roles. He soon sang in the major opera houses in the U.S. and Europe, winning great notices and recording some of his roles. Shicoff experienced severe stage fright well into his career, which caused him to cancel a number of performances. He was known to be a perfectionist, carefully researching and preparing each role, both dramatically and vocally. In 1978, Shicoff married fellow Juilliard graduate, lyric soprano Judith Haddon. After the death of his mother in 1984, Shicoff suffered emotional problems, technical vocal difficulties and increasing performance anxiety. He cancelled numerous performances, and by the end of the 1980s he had developed a reputation for unreliability. Shicoff continued singing at the Met, but in 1991, he left America, fleeing the stresses and headlines engendered by his ongoing divorce proceeding and custody battle concerning his daughter, into a self-described European exile. He lived for three years in Berlin, then Zürich, performing throughout Europe (with a handful appearances in Buenos Aires), and he slowly rebuilt his reputation for reliability. He appeared at Vienna State Opera, La Scala, Paris Opera, Covent Garden, Berlin's Deutsche Oper, Bavarian State Opera, Zurich Opera House and numerous other opera houses and concert halls throughout Europe. By 1997, Shicoff and Haddon finally reached a divorce settlement. Their final decree left Shicoff free to marry soprano Dawn Kotoski, with whom he had lived since 1990, and to renew his relationship with his daughter, Aliza. Shicoff also returned to the Met, as Lensky in Eugene Onegin, to good notices. He has now been heard in nearly 200 performances of 20 roles at the Met. Due to his personal friendship with the Austrian Federal Chancellor, Alfred Gusenbauer, Shicoff was widely expected to follow Ioan Holender as director of the Vienna State Opera (Wiener Staatsoper) in 2010. In a surprise decision, and in defiance of Gusenbauer's publicly stated wish, Austrian Culture Minister Claudia Schmidt appointed Dominique Meyer as director, and Franz Welser-Möst as musical director on June 6, 2007. Shicoff's most famous roles (besides Werther), include the title roles in Tales of Hoffman,and Peter Grimes, Lensky in Eugene Onegin, and Eleazar in La Juive, as well as a number of the Romantic French and Italian lyric and spinto tenor roles. In addition to his opera performances, he has also sung concerts with the Israel Philharmonic conducted by Leonard Bernstein, the Berlin Philharmonic conducted by Claudio Abbado, the San Francisco Symphony conducted by Edo de Waart, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Seiji Ozawa, among others, and at many festivals. Shicoff became Head of Opera at the Mikhailovsky Theatre of St. Petersburg,

Russia in 2015. In recent seasons, Shicoff sang the roles of Cavaradossi in Tosca

and Hoffmann at La Scala and Paris’ Opéra Bastille; Des Grieux in

Manon Lescaut; Don José in Carmen at the Lyric

Opera of Chicago and the Zurich Opera House and Eleazar in Halévy's

La Juive at the Teatro La Fenice in Venice, with Wiener Staatsoper

and the Zurich Opera House, Peter Grimes at the Teatro Regio di Torino.

He has sung also Edgardo in Lucia di Lammermoor, the title role in

Idomeneo, and Rodolfo in La bohème at the Wiener Staatsoper;

Rodolfo in Luisa Miller at the Met; Gabriele Adorno in Simon Boccanegra

at Covent Garden and in Paris; Hermann in Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's

Pique Dame; and Manrico, Cavaradossi and Pinkerton in Madama

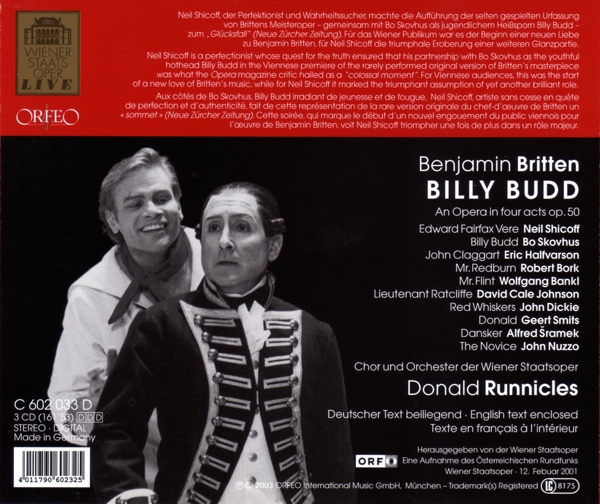

Butterfly at the Zurich Opera House, among others. A regular at Wiener

Staatsoper (where he attained the rank of Kammersänger and the rarely

awarded honorary lifetime membership in the company [shown in photo below])

he continues to triumph mostly in the verismo repertoire, and in February

2011 he repeated his huge success in the role of Captain Vere in Benjamin

Britten's Billy Budd which he sang in the company premiere of the

opera in 2001.

-- Throughout this webpage, names which are

links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

Neil Shicoff at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1979 - Bohème (Rodolfo) with Mitchell/Soviero,

Romero, Ramey, Zilio,

Nolen, Tajo; Chailly, Pizzi, Frisell, Schuler

[Note: A photo of Shicoff as Peter Grimes appears with the Zilio interview.] 1986-87 - Bohème (Rodolfo [one performance only]) with Daniels, Corbelli, Washington, Brown, Kreider, Capecchi; Mauceri, Pizzi, Copley, Schuler Lucia (Edgardo) with Gruberová, Raftery, Howell/Giaiotti; Mackerras/J. Rescigno, Bardon, Reichenbach, Schuler 1987-88 - Faust (Faust) with Gustafson/Soviero, Ramey, Raftery, White, Vozza; Fournet, Samaritani, Diaz, Tallchief, Schuler 1990-91 - Carmen (Don José) with Golden, Cowan, Mazzaria/Hartliep/Lawrence, Foster/Futral, Maultsby; Mata/Pappano, Ponnelle, Calábria. |

BD: Why a hundred and ten per cent?

BD: Why a hundred and ten per cent?  NS: Sometimes it’s very easy, as in a case of Manon

Lescaut, which is a part I very much want to do. I’m thirty-seven

now, and I won’t touch that role before forty-four. I want to

do it very badly, but I’ll wait. Pique Dame [The Queen

of Spades] is a part that I have been consistently offered a lot.

NS: Sometimes it’s very easy, as in a case of Manon

Lescaut, which is a part I very much want to do. I’m thirty-seven

now, and I won’t touch that role before forty-four. I want to

do it very badly, but I’ll wait. Pique Dame [The Queen

of Spades] is a part that I have been consistently offered a lot. NS: Do I think that I have to be as

good? No, I don’t feel that. I have to be as good as I

can be. I put enormous pressure on myself to be better than I

was at the last show. Do I relate that to how well Luciano sang

Ballo the other night? I don’t do that because he’s a different

tenor. He’s a quite spectacular tenor, and when I feel genuine

admiration for singers, it’s easier when they’re not your age. If

I were the same age as these tenors, it might be more difficult, but there’s

an age difference.

NS: Do I think that I have to be as

good? No, I don’t feel that. I have to be as good as I

can be. I put enormous pressure on myself to be better than I

was at the last show. Do I relate that to how well Luciano sang

Ballo the other night? I don’t do that because he’s a different

tenor. He’s a quite spectacular tenor, and when I feel genuine

admiration for singers, it’s easier when they’re not your age. If

I were the same age as these tenors, it might be more difficult, but there’s

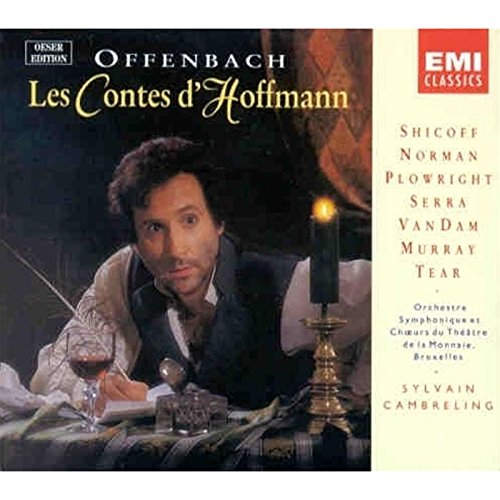

an age difference. NS: Studio recordings are never as good

as performances because they’re bigger than life. Firstly, you

hear the voice much clearer, but you don’t have the ambiance of the

voice that goes into the acoustics of a theater. I wouldn’t call

them a fraud. It becomes a fraud when you can’t sing a note softly,

and they make it soft for you; or when you can’t sing a high note.

Let’s say you have to sing a high C, and you only have a B. So

you record the B, and they jack it up to a C. I’ve never had to do

that. I haven’t made that many recordings. I’ve done Macbeth

and Rigoletto, and I’m now completing Hoffmann, which comes

out after this summer. I haven’t asked them to do something I haven’t

been able to do. I suppose you could say it would be a fraud if

they put a tremendous diminuendo in somewhere that you couldn’t do.

I haven’t needed to do that. I haven’t seen that either with

the colleagues I’ve worked with.

NS: Studio recordings are never as good

as performances because they’re bigger than life. Firstly, you

hear the voice much clearer, but you don’t have the ambiance of the

voice that goes into the acoustics of a theater. I wouldn’t call

them a fraud. It becomes a fraud when you can’t sing a note softly,

and they make it soft for you; or when you can’t sing a high note.

Let’s say you have to sing a high C, and you only have a B. So

you record the B, and they jack it up to a C. I’ve never had to do

that. I haven’t made that many recordings. I’ve done Macbeth

and Rigoletto, and I’m now completing Hoffmann, which comes

out after this summer. I haven’t asked them to do something I haven’t

been able to do. I suppose you could say it would be a fraud if

they put a tremendous diminuendo in somewhere that you couldn’t do.

I haven’t needed to do that. I haven’t seen that either with

the colleagues I’ve worked with.|

Malas has taught singing master classes at the Blossom Music Festival, the San Francisco Opera Center, the Santa Fe Opera, the European Center for Opera and Vocal Studies in Brussels, the Israel Vocal Studies Center, the English National Opera, the Metropolitan Opera National Council, Westminster Choir College, and Rutgers University. She has also served as a judge for the Metropolitan Opera National Council auditions. Most notably, in 1993, she taught master classes in collaboration with her mentors Joan Sutherland, Richard Bonynge, and Luigi Alva in association with the Sydney Opera House, at their first Opera Symposium. A native of New York City, Malas, a mezzo-soprano, graduated from the Curtis Institute of Music. She then sang with opera companies including Santa Fe, Boston, Miami, Washington, D.C., Baltimore, San Diego, and Milwaukee, and made appearances with the Marlboro and Casals Festivals as well as concert appearances with the Philadelphia Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic. She is featured on a definitive recording of Brahms’s Liebeslieder Waltzes under the direction of Rudolf Serkin and Leon Fleisher. Malas lives in Manhattan with her husband, renowned operatic bass and voice teacher Spiro Malas. They spend wonderful times there with their two sons Alexis and Nicol and their families, including their five beautiful grandchildren: Sascha, Reed, Grant, Max, and Flynn. |

BD: Are you looking forward to working with Maestro Rosenthal?

BD: Are you looking forward to working with Maestro Rosenthal? BD: Are you optimistic about the future

of opera?

BD: Are you optimistic about the future

of opera? BD: [At this point, Aliza again chimed in, demanding

her father’s

attention.] As a father, what are you going to tell your

daughter about opera? And is it going to be different because

you’re actually in it?

BD: [At this point, Aliza again chimed in, demanding

her father’s

attention.] As a father, what are you going to tell your

daughter about opera? And is it going to be different because

you’re actually in it? BD: Do you think opera works well

in translation?

BD: Do you think opera works well

in translation? NS: He’s a pretty neurotic character. There are

three women that are one woman. He says, that. These three

women — Olympia, Antonia, and Giulietta

— are Stella. I played them as separate women when

I was dealing with them. I don’t play them as three facets of

the same woman, although I say that in the Prologue. But they’re

individuals for me at the moment, and in each case, he doesn’t consummate

his relationship with them. Various things happen because of this

evil figure that looms throughout the opera.

NS: He’s a pretty neurotic character. There are

three women that are one woman. He says, that. These three

women — Olympia, Antonia, and Giulietta

— are Stella. I played them as separate women when

I was dealing with them. I don’t play them as three facets of

the same woman, although I say that in the Prologue. But they’re

individuals for me at the moment, and in each case, he doesn’t consummate

his relationship with them. Various things happen because of this

evil figure that looms throughout the opera. NS: No, it’s a contest of me versus me, clearly.

It has nothing to do with the audience. For me, what the audience

is for is to try to show them a part of myself through this character.

That’s an interesting point. They’re very important to evening. It’s

not like doing it in a practice room. What happens to me is frequently

I can’t get through a piece in a room. Given the pressure of

having to do it in front of three thousand people, my body reacts chemically,

much differently than it would if they weren’t sitting out there.

Even in this Lucia, there are times at the end of the piece when

there’s no way I’d be able to finish the piece. It’s very high

at the end, and I sing it in the original key, and that key is a high

key. But in front of a public, what always crosses my mind is that

I’m going to die if I don’t do this now. I’m literally going to die

up here if I don’t finish this, and so I finish it. It may not sound

fantastic, but if I didn’t have that, I wouldn’t put myself through it.

I would say that I’m going to do it another day, but that’s not what

I want to get into. What I want to get into is that with an audience

there’s an electricity that exists, and that is what’s between us.

There are nights that audiences are total disasters, and it takes a lot

out of my performing because I feel they’re wearing white ties, and they’re

not involved, and they’ve got a big gala after-party. Then the performance

simply belongs to me. I do it for me. That doesn’t mean

that if it’s a gala performance that they’re not necessarily involved,

but that can happen. It can happen a lot of nights. You can

grab an audience that just came from work, they’re

tired, they couldn’t eat, but they are involved. They can pull

a lot out of me and I can give them a lot.

NS: No, it’s a contest of me versus me, clearly.

It has nothing to do with the audience. For me, what the audience

is for is to try to show them a part of myself through this character.

That’s an interesting point. They’re very important to evening. It’s

not like doing it in a practice room. What happens to me is frequently

I can’t get through a piece in a room. Given the pressure of

having to do it in front of three thousand people, my body reacts chemically,

much differently than it would if they weren’t sitting out there.

Even in this Lucia, there are times at the end of the piece when

there’s no way I’d be able to finish the piece. It’s very high

at the end, and I sing it in the original key, and that key is a high

key. But in front of a public, what always crosses my mind is that

I’m going to die if I don’t do this now. I’m literally going to die

up here if I don’t finish this, and so I finish it. It may not sound

fantastic, but if I didn’t have that, I wouldn’t put myself through it.

I would say that I’m going to do it another day, but that’s not what

I want to get into. What I want to get into is that with an audience

there’s an electricity that exists, and that is what’s between us.

There are nights that audiences are total disasters, and it takes a lot

out of my performing because I feel they’re wearing white ties, and they’re

not involved, and they’ve got a big gala after-party. Then the performance

simply belongs to me. I do it for me. That doesn’t mean

that if it’s a gala performance that they’re not necessarily involved,

but that can happen. It can happen a lot of nights. You can

grab an audience that just came from work, they’re

tired, they couldn’t eat, but they are involved. They can pull

a lot out of me and I can give them a lot. BD: Is opera art, or is opera entertainment?

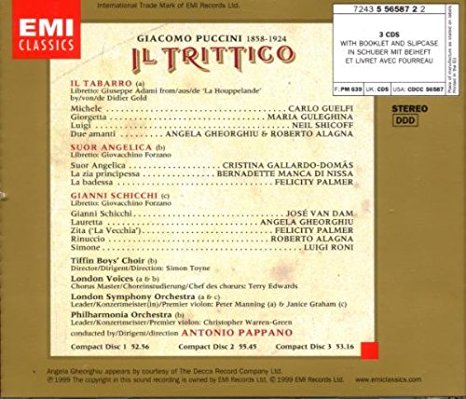

BD: Is opera art, or is opera entertainment? BD: The Met is also a very big house. [Vis-a-vis

the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Bernadette Manca di Nissa,

and Felicity Palmer.]

BD: The Met is also a very big house. [Vis-a-vis

the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Bernadette Manca di Nissa,

and Felicity Palmer.]© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 20, 1986. Portions were broadcast on WNIB twice in 1989, and again in 1993, 1994, and 1999. This transcription was made in 2018, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.