A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

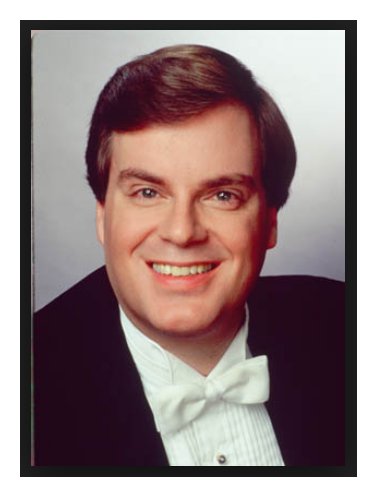

| The renowned American tenor John

Aler is one of the most acclaimed and admired singers on the

international stage. A consummate artist, he has been a frequent

performer with such orchestras as the New York Philharmonic, the

Cleveland and Philadelphia Orchestras, the Los Angeles Philharmonic and

the symphony orchestras of Boston, Chicago and San Francisco. He

has sung in Europe with the Berlin Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus,

Orchestre Nationale de France, and the BBC Symphony, among many others,

appearing with the world’s most respected conductors, including James

Conlon, Charles Dutoit,

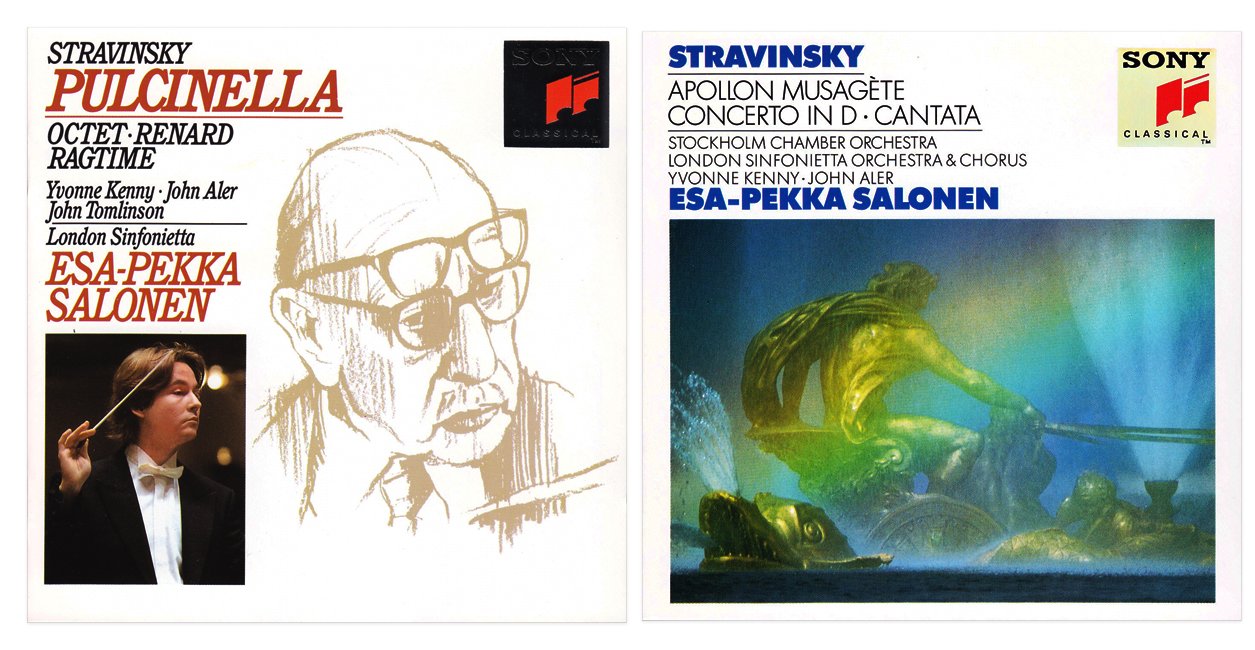

Daniel Barenboim, Pierre Boulez, Kurt Masur, Esa-Pekka

Salonen, Erich

Leinsdorf, Zubin

Mehta, Simon Rattle, Michael

Tilson Thomas, Herbert

Blomstedt, and Leonard

Slatkin, to name a few. He has performed at the major opera

houses of the world, including the Royal Opera Covent Garden, Deutsche

Oper Berlin, Vienna, Munich, Salzburg, Hamburg, Geneva, Madrid, and

Brussels, as well as the New York City Opera, the Washington Opera, and

Santa Fe. He is a regular performer at the major American summer

festivals, including Ravinia, Aspen, Chautauqua, Newport, and Grant

Park. Performances highlights of recent seasons have included Britten’s War Requiem with the Moscow Philharmonic and the Munich Philharmonic under James Conlon, Berlioz’s Damnation of Faust with Carlos Kalmar at the Grant Park Music Festival, Mendelssohn’s Elijah with the Dallas Symphony under Claus Peter Flor, Britten’s Saint Nicholas with the Indianapolis Symphony under their conductor laureate, Raymond Leppard, Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis at Strathmore Hall with the National Philharmonic, and his 24th season at the Cincinnati May Festival, where he performed Bach’s St. Matthew Passion and Mozart’s “Great” Mass in c minor under James Conlon. He returns to the May Festival in 2011 to sing Haydn’s Heiligemesse. Highlights of 2010 include Britten’s Canticle II, Abraham and Isaac with Marietta Simpson performed at the Kennedy Center, the Ravinia Festival where he sang Bernstein’s Candide under John Axelrod, and Mozart’s Nozze di Figaro, conducted by James Conlon with the Chicago Symphony. Anther recent major performance is Corigliano's Dylan Trilogy with Leonard Slatkin and the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington and the Carnegie Hall. Mr. Aler has an extensive concert repertoire, which ranges from the Evangelist in the Passions of Bach to the War Requiem and Serenade for Tenor Horn and Strings of Benjamin Britten and Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd, which he performed with the San Francisco Symphony, at the Ravinia Festival under Andrew Litton, and with the New York Philharmonic, who recorded it for a limited release under its New York Philharmonic Special Edition label.  John Aler is featured on three Grammy Award-winning recordings: in the role of Jupiter in an all-star recording of Handel’s Semele with John Nelson and the English chamber Orchestra for DGG, which won “Best Opera Recording”; Bartók’s Cantata Profana with Pierre Boulez and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, also on DGG, which won “Best Classical Album”; and the Berlioz Requiem with the Atlanta Symphony led by Robert Shaw on Telarc, which won for “Best Vocal Soloist.” He has an extensive discography and can be heard on more than 60 recordings on DGG, Decca, EMI/Angel, Telarc, Teldec, and more than a dozen other labels. A recitalist of note, he has several recordings of chansons, Lieder and song including a solo album entitled “Songs We Forgot to Remember” on Delos. In December 2006, he recorded Bach’s Coffee Cantata with the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center in a downloadable format for Deutsche Grammophon. A native of Baltimore, John Aler (born October 4, 1949) is an alumnus of the Catholic University in Washington, DC and the Juilliard School. -- Names which are links in this

box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website.

BD

|

BD: [With a

gentle nudge] You don’t want to do Siegfried tomorrow?

BD: [With a

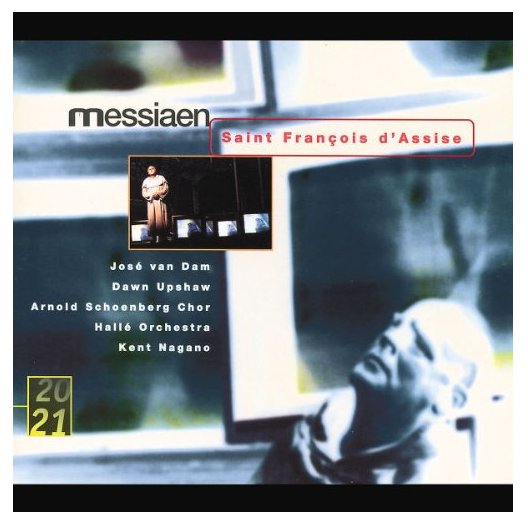

gentle nudge] You don’t want to do Siegfried tomorrow?(...) Because of its scale,

''St. Francois'' will always be a rare work, and this is right: it

needs to be a special occasion. But it also needs to be available. For

the moment, its future lies with the 1992 Salzburg Festival production,

which has been brought back this year and may now appear again in Paris

and Berlin. Sooner or later the work must also be done in the United

States. Coming to the virtues of the present revival, it is hard

to know where to start. Triumph was general at Monday night's

performance: for Jose van Dam in the title role; for all the other

soloists; for Kent Nagano, the conductor; for his magnificent British

orchestra, the Halle of Manchester, and for the Arnold Schoenberg Choir

from Vienna. Coming to the virtues of the present revival, it is hard

to know where to start. Triumph was general at Monday night's

performance: for Jose van Dam in the title role; for all the other

soloists; for Kent Nagano, the conductor; for his magnificent British

orchestra, the Halle of Manchester, and for the Arnold Schoenberg Choir

from Vienna.Mr. van Dam, who has been St. Francis in every staged performance so far, sings with unswerving force. He sounds like a dark, low trumpet, always there to the full, always secure, and at first his certainty is forbidding. But this is surely how Messiaen wanted it. The opening scene is there to show that Francis's feelings are not earthly but divine: he shows compassion for an anxious young monk not by lending comfort but by demanding more suffering. As the performance goes on, Mr. van Dam's hardy strength, formidably sustained throughout this long role, proves itself. Sentimentality is a trivial loss. Power counts. Dawn Upshaw just is, simply and purely, the voice of the Angel. Chris Merritt writhes with vocal fury as the Leper. Urban Malmberg gives a fine, appealing performance as Brother Leo, his youthful baritone seeming to pick up resilience from Mr. van Dam. Contrasted tenors, Guy Renard and John Aler, enact the distemperate Brother Elia and the head-in-the-clouds Brother Masseo. Ms. Upshaw, Mr. Malmberg and Mr. Aler were all there with Mr. van Dam when this production was first done, and their performances have grown with his. It is not a question of finding more in the music, but of trying less. There is serenity and acceptance in what they do. Perhaps we are beginning to understand what we have got in this work -- or at least to understand what a puzzle and a challenge we have got. Besides being huge and humble, the score is as ancient as plainsong and as new as yesterday in its musical resources. Most paradoxically of all, it is, in a godless century, as bold as an icon. Any staging is bound to be measured by its failures, and Peter Sellars has defiantly kept his most extravagant ones from 1992: the video monitors that litter the stage, flickering with unwanted images. But he is responsible, too, for visual wonder, in the workings of a huge array of fluorescent tubes responding to the light and color in the music. And there is appropriateness in the quiet care with which the principals onstage handle one another and comport themselves. (...) -- Part of a review in The New York Times by Paul

Griffiths, August 27, 1998

[Photo of recording added for this website presentation] |

BD: Is that the

way you like it?

BD: Is that the

way you like it? JA: Theoretically you can but

it’s not always the case. For instance, during Stravinsky’s

Renard he used an instrument

called a cimbalom, the Hungarian gypsy instrument. It is not only

very hard to find, but

incredibly hard to find the player!

JA: Theoretically you can but

it’s not always the case. For instance, during Stravinsky’s

Renard he used an instrument

called a cimbalom, the Hungarian gypsy instrument. It is not only

very hard to find, but

incredibly hard to find the player! JA: Yes.

I like them a lot,

actually. I was rather pleased with them, particularly

considering the mikeing situation. There’s

only one mike, for instance, that was used for the Liszt

recording! They only had one mike set up about twelve feet high

in the air above me and the pianist,

Daniel Blumenthal. I thought that came out very

well. I was surprised how true that sounded. I don’t like

over-produced recordings.

JA: Yes.

I like them a lot,

actually. I was rather pleased with them, particularly

considering the mikeing situation. There’s

only one mike, for instance, that was used for the Liszt

recording! They only had one mike set up about twelve feet high

in the air above me and the pianist,

Daniel Blumenthal. I thought that came out very

well. I was surprised how true that sounded. I don’t like

over-produced recordings.

JA: Yes. Kraus had the

role of Masaniello, and the opera sometimes is called Masaniello. The second tenor

role is called Alphonse, who is the beloved of the soprano. The

opera is named

after La Muette, which means the mute girl. It’s a dancing part,

so she’s from the ballet. Then there are a

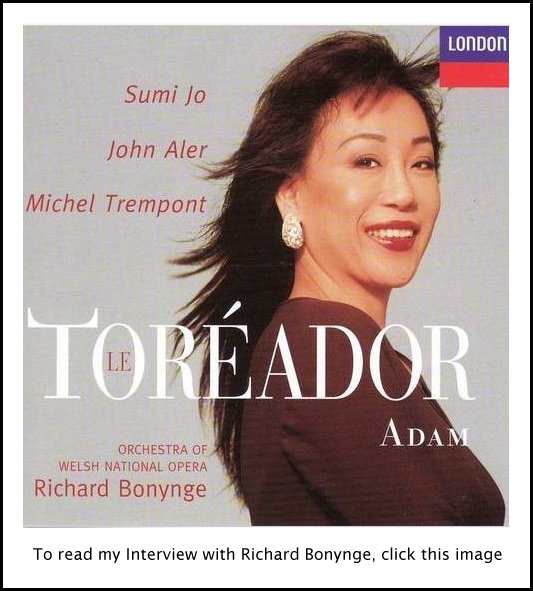

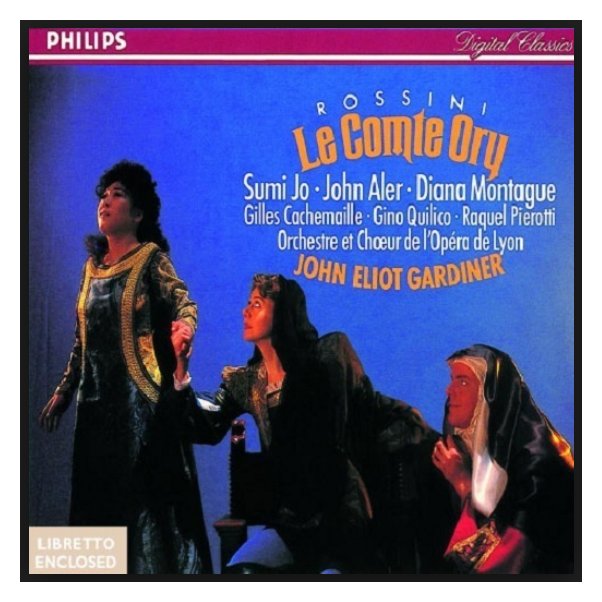

couple of things for Philips conducted by John Eliot Gardiner including

Comte Ory of Rossini, which is

a

very good recording with Sumi Jo [see

photo of booklet cover at right with Aler as a nun!], and Iphigénie

en Tauride. Iphigénie

en Aulide is on Erato, as is another Rameau opera which called Les Boréades. Those

are also with Gardiner, so there’s kind of a lot. I did a couple

of complete

Messiahs, one on RCA with

Richard Westenburg dn the Music Sacra Chorus and Orchestra from New

York, and one on EMI with Andrew Davis and the Toronto Symphony.

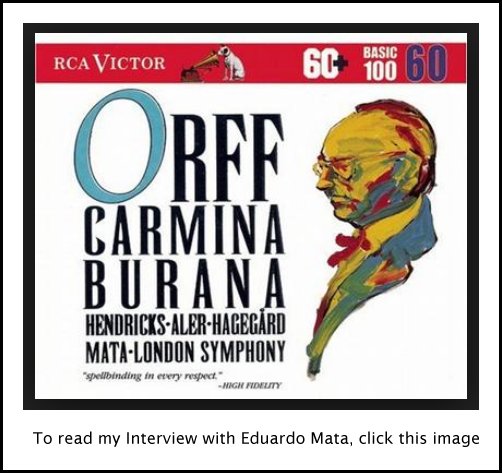

I’ve also done a couple of Carmina

Buranas.

JA: Yes. Kraus had the

role of Masaniello, and the opera sometimes is called Masaniello. The second tenor

role is called Alphonse, who is the beloved of the soprano. The

opera is named

after La Muette, which means the mute girl. It’s a dancing part,

so she’s from the ballet. Then there are a

couple of things for Philips conducted by John Eliot Gardiner including

Comte Ory of Rossini, which is

a

very good recording with Sumi Jo [see

photo of booklet cover at right with Aler as a nun!], and Iphigénie

en Tauride. Iphigénie

en Aulide is on Erato, as is another Rameau opera which called Les Boréades. Those

are also with Gardiner, so there’s kind of a lot. I did a couple

of complete

Messiahs, one on RCA with

Richard Westenburg dn the Music Sacra Chorus and Orchestra from New

York, and one on EMI with Andrew Davis and the Toronto Symphony.

I’ve also done a couple of Carmina

Buranas. BD: But you

can’t force it.

BD: But you

can’t force it. JA: Well, I’ve

gotten a couple like that.

JA: Well, I’ve

gotten a couple like that. JA: It is for

me, yes! It’s great. I’m

really lucky. I love it! I like singing with other

people. I

love ensemble singing.

JA: It is for

me, yes! It’s great. I’m

really lucky. I love it! I like singing with other

people. I

love ensemble singing.© 1992 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at his hotel in Chicago on January 13, 1992. Portions were broadcast on WNIB later that year, and again in 1994 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.