A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

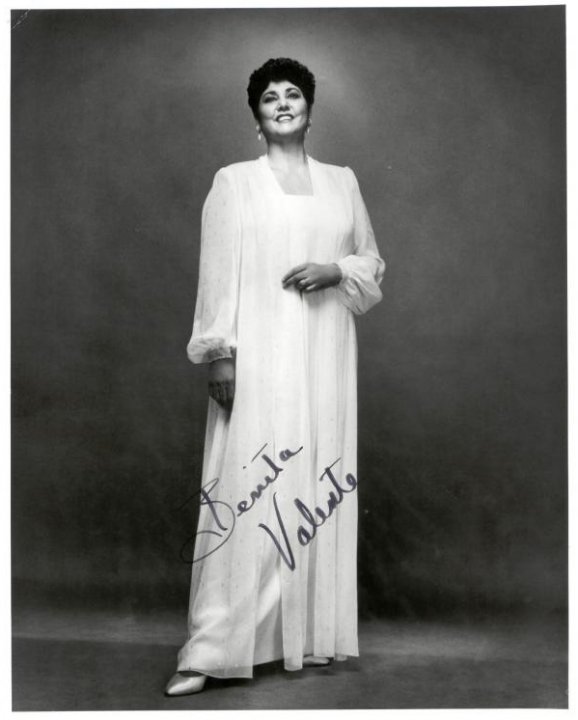

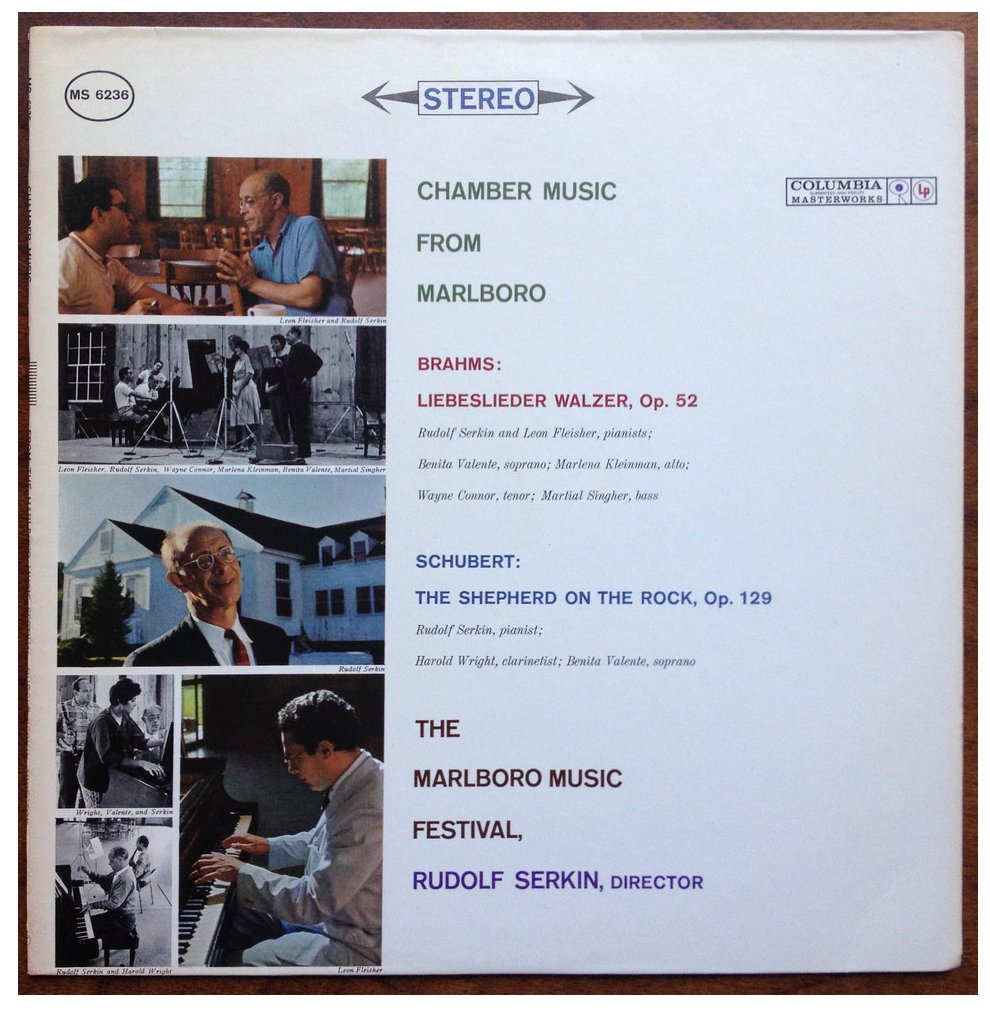

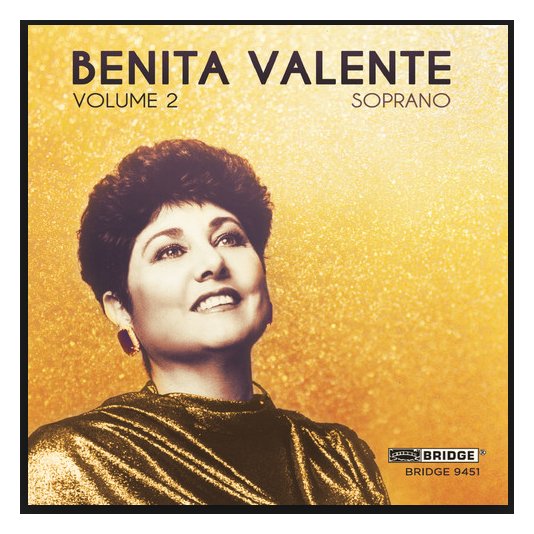

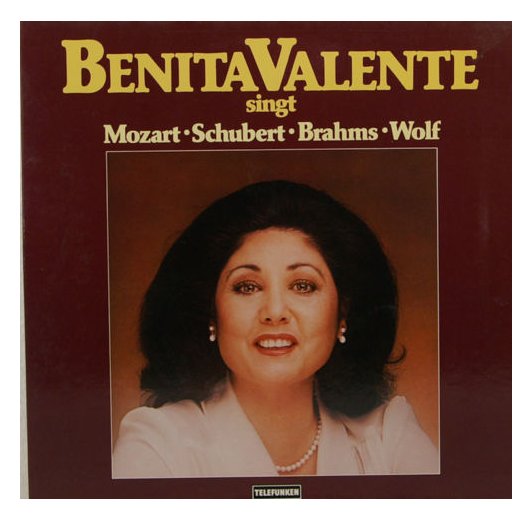

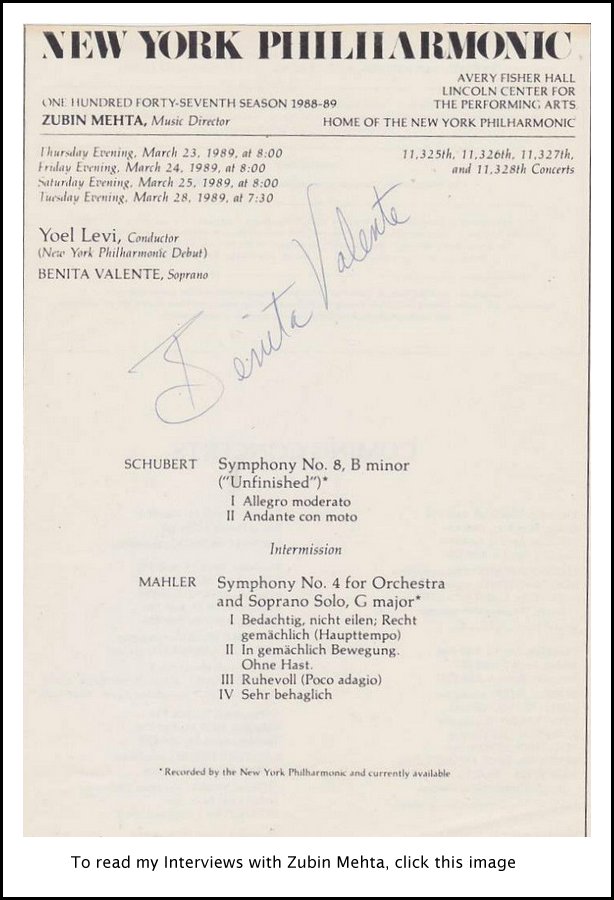

| Benita Valente (Soprano) Born: October 19, 1934 - Delano, California, USA The distinguished American soprano, Benita Valente, began serious musical training with Chester Hayden at Delano High School. At 16, she became a private pupil of Lotte Lehmann, and at 17 received a scholarship to continue her studies with Lehmann at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, where she got her initial professional music experience. There she also met and collaborated with Marilyn Horne. In 1955 she won a scholarship to the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where she studied with Martial Singher. Upon graduation in 1960, she made her formal debut in a Marlboro (Vermont) Festival concert. There she performed with Rudolf Serkin, Felix Galimir and Harold Wright. In October 1960 she made her New York concert debut at the New School for Social Research. After winning the Metropolitan Opera Auditions in 1960, she pursued further studies with Margaret Harshaw. She then sang with the Freiburg im Breisgau Opera, making her debut there as Parnina in Die Zauberflöte in 1962. After appearances with the Nuremberg Opera in 1966, she returned to the USA and established herself as a versatile recitalist, soloist with orchestra, and opera singer. Her interpretation of Pamina was especially well received, and it was in that role that she made her Metropolitan Opera debut in New York in September 1973. Her roles at the Metropolitan Opera have included also Gilda, Nanetta, Susanna, Ilia, and Almirena. Other roles include Euridice at Santa Fe, the Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro in Washington, and Dalilah in Florence. Festival appearances include Tanglewood, Aspen, Ravinia, Grand Tetons, Santa Fe, Vienna, Edinburgh, and Lyon.

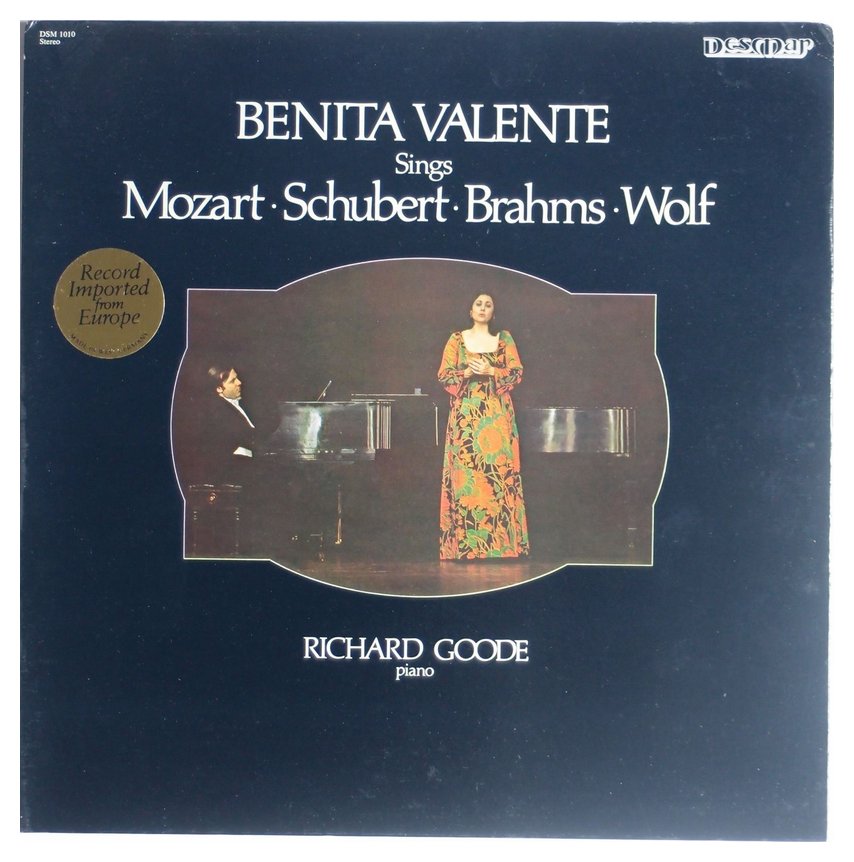

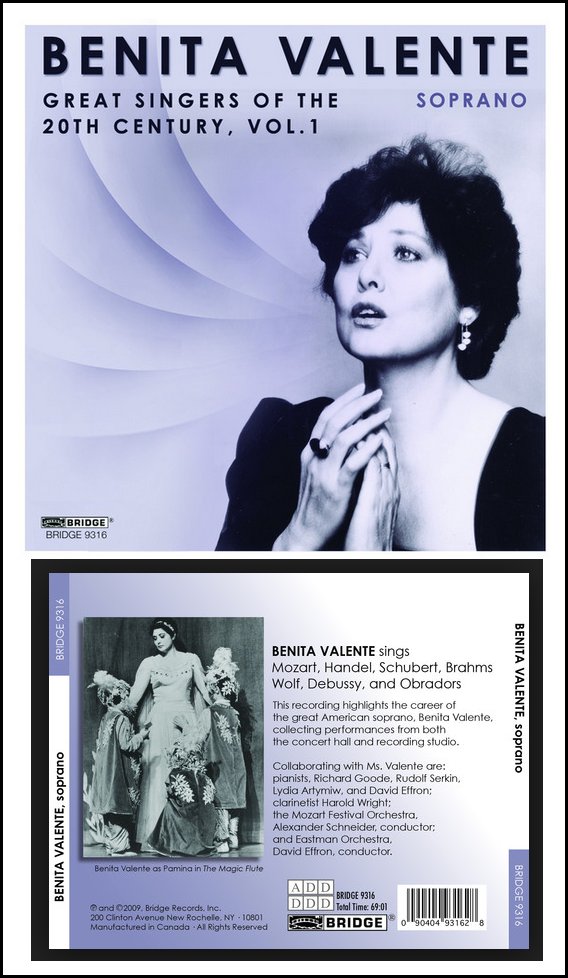

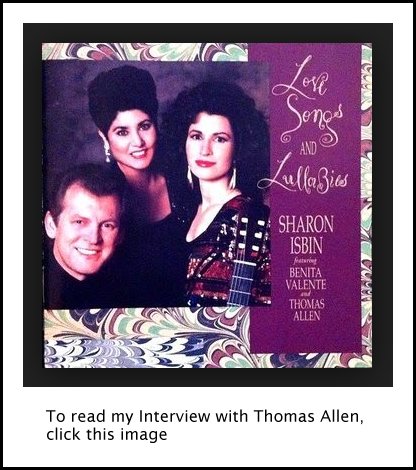

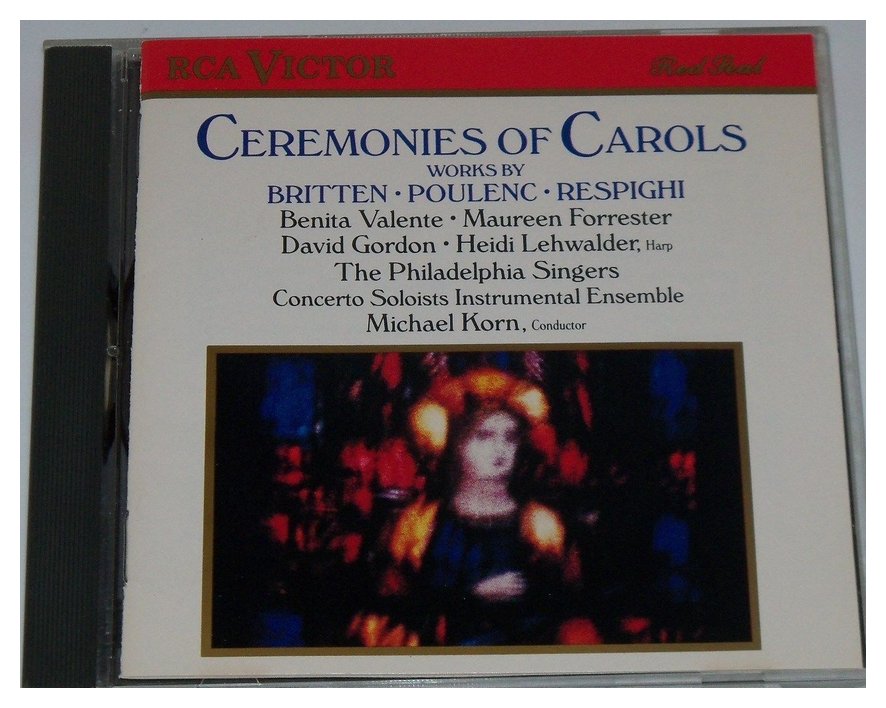

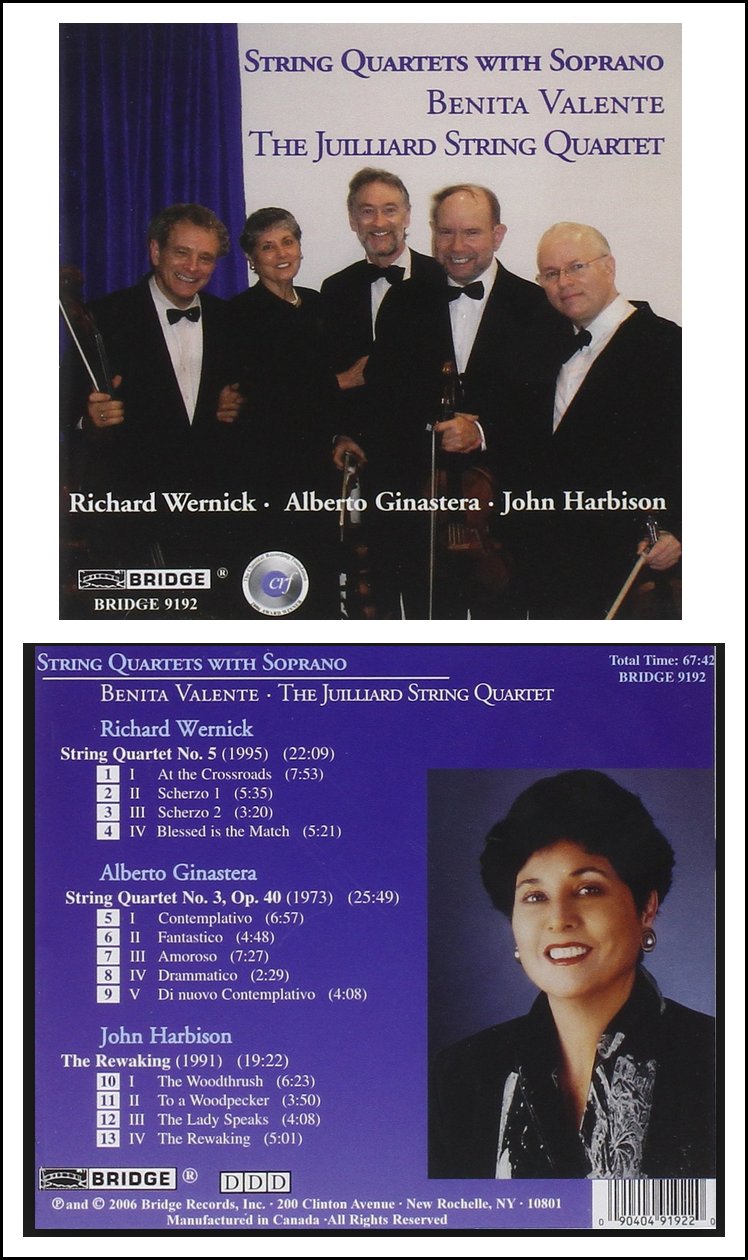

Benita Valente has been an internationally celebrated interpreter of Lieder, chamber music, oratorio, and opera. Her keen musicianship encompasses an astounding array of styles, from the Baroque of J.S. Bach and George Frideric Handel to the varied idioms of today's leading composers. She won praise for her performances in operas by Monteverdi, G.F. Handel, Verdi, Puccini, and Benjamin Britten. Her extensive recital and concert repertoire ranges from Schubert to Alberto Ginastera. Especially noted for her collaborations with living composers, she has sung in many chamber music and recital performances, often in world premieres. As the soprano in residence at the prestigious Marlboro Festival her performances and recordings with the legendary pianist Rudolf Serkin won great acclaim. Other major chamber music collaborators have included the Guarneri and Juilliard and Orion String Quartets, cellist Yo-Yo Ma, clarinetist Richard Stoltzman, guitarist Sharon Isbin and pianists Peter Serkin, Emanuel Ax, Leon Fleisher, Richard Goode, Malcolm Bilson and Cynthia Raim. Benita Valente has been orchestral soloist with virtually every important conductor and orchestra in the world. She has sung under the batons of Claudio Abbado, Daniel Barenboim, Mario Bernardi, Leonard Bernstein, Sergiu Comissiona, James Conlon, Edo de Waart, Christoph Eschenbach, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Rafael Kubelík, Erich Leinsdorf, Raymond Leppard, James Levine, Kurt Masur, Riccardo Muti, Seiji Ozawa, Robert Shaw, Leonard Slatkin and Klaus Tennstedt, and with every major symphony in the USA, Canada and Europe. Valente has been recorded by seventeen recording companies. She received a Grammy Award for her recording of Arnold Schoenberg's Quartet No.2 and a Grammy nomination for her recording of Haydn's Seven Last Words of Christ, both performed with The Juilliard String Quartet. Her recent recordings include music of Ralph Vaughan Williams, Debussy, and Bolcom. Valente was the 1999 Recipient of Chamber Music America's Highest Award: The Richard J. Bogomolny National Service Award, the first vocalist to receive the award in its twenty-year history. -- Edited from the Bach Cantatas

website

-- Names which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

Valente:

When all of that is past, then the joys come back again, and yes, when it’s

over with, you feel that it was a wonderful piece and I’m glad I did it.

I think I’ll feel that way about the Shostakovich, too. It is a beautiful

piece.

Valente:

When all of that is past, then the joys come back again, and yes, when it’s

over with, you feel that it was a wonderful piece and I’m glad I did it.

I think I’ll feel that way about the Shostakovich, too. It is a beautiful

piece. BD: Do you enjoy the technical side of making records?

BD: Do you enjoy the technical side of making records? Valente: I try to do all of my Lieder recitals in one period of time

because I can’t jump from Lieder

recitals to opera. When I’m doing a Lieder recital, I want to do just that

and not have my attention divided by having other kinds of repertoire to work.

First of all, it takes a lot of time and work to find the kind of program

you want to do. You have to sort it out, decide what songs you want

to do, rehearse it with your pianist, get it ready and perform it. It

takes months. So I allow two or three months a season to do that, and

then I perform this Lieder program

over the next two months.

Valente: I try to do all of my Lieder recitals in one period of time

because I can’t jump from Lieder

recitals to opera. When I’m doing a Lieder recital, I want to do just that

and not have my attention divided by having other kinds of repertoire to work.

First of all, it takes a lot of time and work to find the kind of program

you want to do. You have to sort it out, decide what songs you want

to do, rehearse it with your pianist, get it ready and perform it. It

takes months. So I allow two or three months a season to do that, and

then I perform this Lieder program

over the next two months. Valente:

I don’t think so. My voice is not going to change in the direction that

this piece would need. It’s pretty dramatic singing. There is

one aria that is higher, and I could probably do very easily, but the rest

of the role keeps sinking down into the lower register and is heavier.

Valente:

I don’t think so. My voice is not going to change in the direction that

this piece would need. It’s pretty dramatic singing. There is

one aria that is higher, and I could probably do very easily, but the rest

of the role keeps sinking down into the lower register and is heavier. Valente: Yes, they are. It depends on

their education, too. We were talking about a place like Cincinnati.

I go there a couple times every year, and I feel the audience is educated.

They have been doing music, they’ve been having music in their city for many

years, and they have a tradition. When you go to Germany, that’s what

you feel — the tradition. And the size of the

halls is important. They haven’t built the halls large enough to hold

thousands of people because of the money. They built them because of

the art, because of certain needs of the composers, and certain kind of space.

You don’t want to be too far away from those halls, and the public is just

so educated. They are willing to listen to anything. We did one

contemporary opera a season, and everybody in town would be talking about

how they hated it or loved it or whatever. But at least they were talking

about it, and if they met you on the street, they would speak to you and say

how wonderful it is that you’re and opera singer, that you’re in their country

to sing, and how much they appreciated us and that our work was totally accepted.

Whereas if you’re a singer in the United States, there are still those thousands

of people who think you just stand on the stage and sing. It’s slowly

changing, but it’s taking a while. They don’t understand there’s work

involved. It may be something that you love very much and wouldn’t

want to trade anything for. Nonetheless, there’s a lot of work and

knowledge that goes into it, but they don’t realize that. It is partly

that we were so busy settling our country that we have not caught up yet

with the arts.

Valente: Yes, they are. It depends on

their education, too. We were talking about a place like Cincinnati.

I go there a couple times every year, and I feel the audience is educated.

They have been doing music, they’ve been having music in their city for many

years, and they have a tradition. When you go to Germany, that’s what

you feel — the tradition. And the size of the

halls is important. They haven’t built the halls large enough to hold

thousands of people because of the money. They built them because of

the art, because of certain needs of the composers, and certain kind of space.

You don’t want to be too far away from those halls, and the public is just

so educated. They are willing to listen to anything. We did one

contemporary opera a season, and everybody in town would be talking about

how they hated it or loved it or whatever. But at least they were talking

about it, and if they met you on the street, they would speak to you and say

how wonderful it is that you’re and opera singer, that you’re in their country

to sing, and how much they appreciated us and that our work was totally accepted.

Whereas if you’re a singer in the United States, there are still those thousands

of people who think you just stand on the stage and sing. It’s slowly

changing, but it’s taking a while. They don’t understand there’s work

involved. It may be something that you love very much and wouldn’t

want to trade anything for. Nonetheless, there’s a lot of work and

knowledge that goes into it, but they don’t realize that. It is partly

that we were so busy settling our country that we have not caught up yet

with the arts. Valente: I don’t know what advice to give.

You either have the gift or you don’t and keep plodding along. What

advice I do have for young musicians, or young singers, is that they have

to have a tremendous amount of patience and don’t leave any stone unturned

because a lot of it is experimental. You don’t know how it’s going to

work. You don’t know how your voice works. You don’t know how

your instrument works. We singers usually don’t start as young as the

instrumentalists, and it takes us a while to catch up. It’s not just

ingrained. It’s something we want to do and we go through all the frustrations.

When you hit your late teens you finally start taking voice lessons, and

you get to 25 and people are saying you’re too old already, which is all

silly. Singers themselves say we’re too old when we’re 25, so just

have a lot of patience and keep working. Be expressive. Enjoy

it. It only goes by once.

Valente: I don’t know what advice to give.

You either have the gift or you don’t and keep plodding along. What

advice I do have for young musicians, or young singers, is that they have

to have a tremendous amount of patience and don’t leave any stone unturned

because a lot of it is experimental. You don’t know how it’s going to

work. You don’t know how your voice works. You don’t know how

your instrument works. We singers usually don’t start as young as the

instrumentalists, and it takes us a while to catch up. It’s not just

ingrained. It’s something we want to do and we go through all the frustrations.

When you hit your late teens you finally start taking voice lessons, and

you get to 25 and people are saying you’re too old already, which is all

silly. Singers themselves say we’re too old when we’re 25, so just

have a lot of patience and keep working. Be expressive. Enjoy

it. It only goes by once. Valente: If we’d half the size hall, more people

might have stayed. We would’ve had to have more performances and a smaller

audience each time, and they would’ve been more caught up in what was happening

on the stage. But the Academy of Music seats three thousand or so,

and I guess the people in the last reaches just didn’t feel like they were

having anything to do with the stage. So they just left. I think

that’s part of it.

Valente: If we’d half the size hall, more people

might have stayed. We would’ve had to have more performances and a smaller

audience each time, and they would’ve been more caught up in what was happening

on the stage. But the Academy of Music seats three thousand or so,

and I guess the people in the last reaches just didn’t feel like they were

having anything to do with the stage. So they just left. I think

that’s part of it.

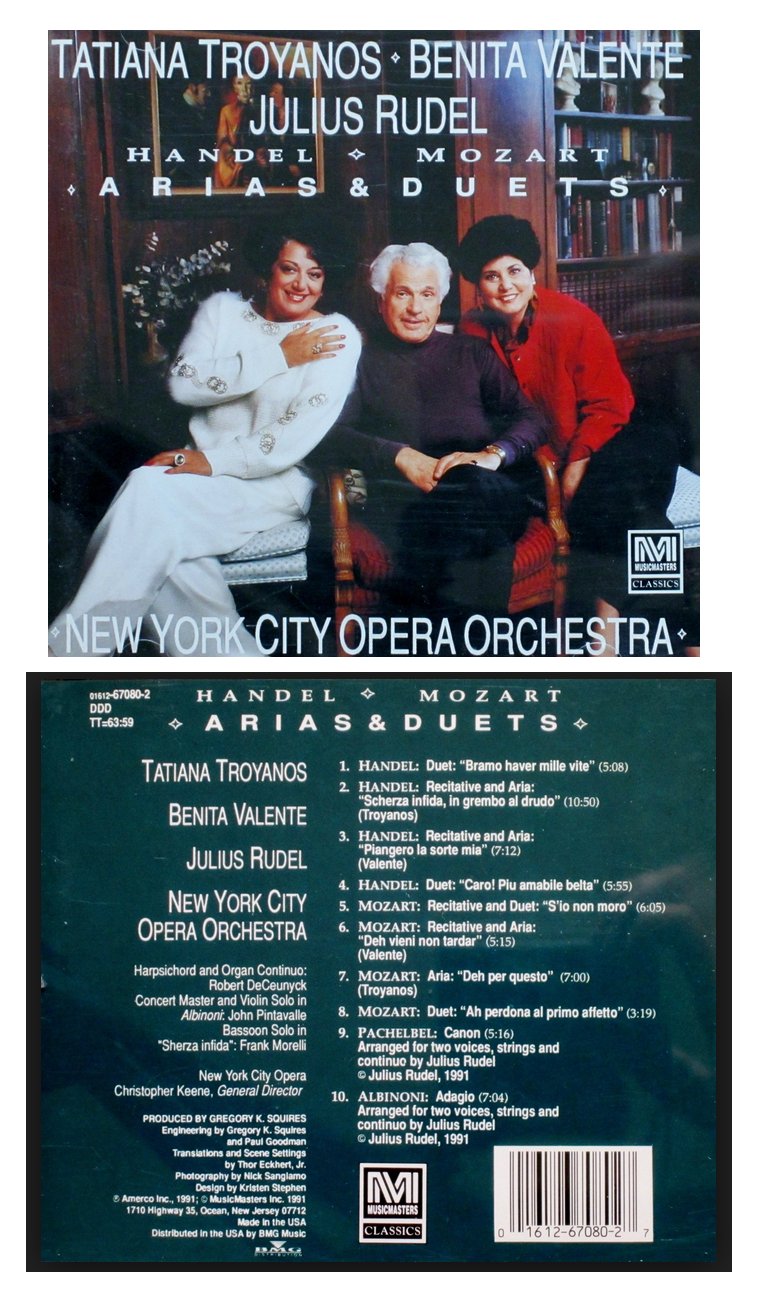

To read my Interview with Tatiana Troyanos, click HERE. To read my Interview with Julius Rudel, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Maureen Forrester, click HERE. To read my Interview with David Gordon, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Richard Wernick, click HERE. To read my Interview with John Harbison, click HERE.

|

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on May 7, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB 1989 and again in 1994 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2016, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.