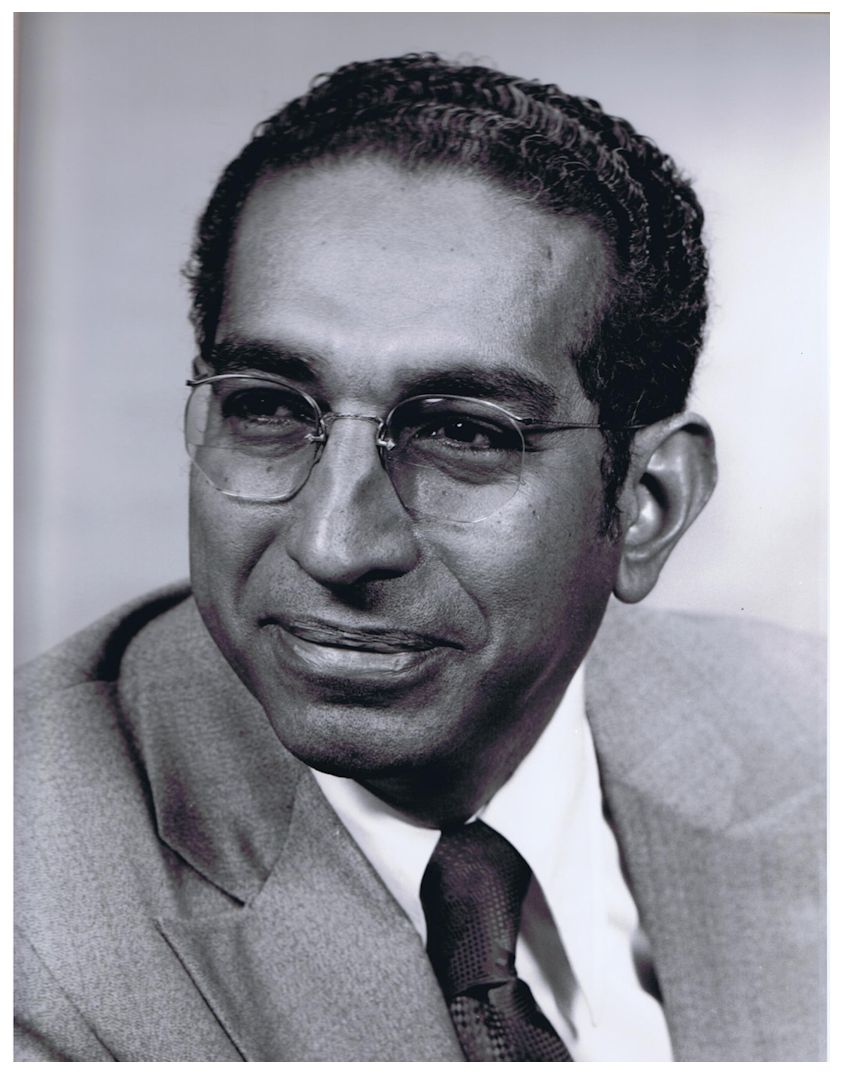

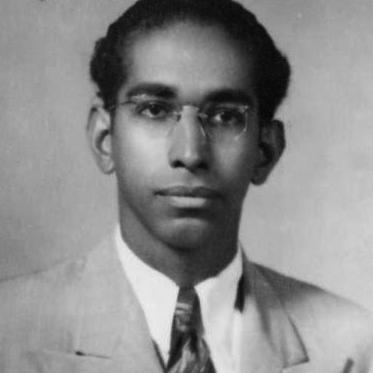

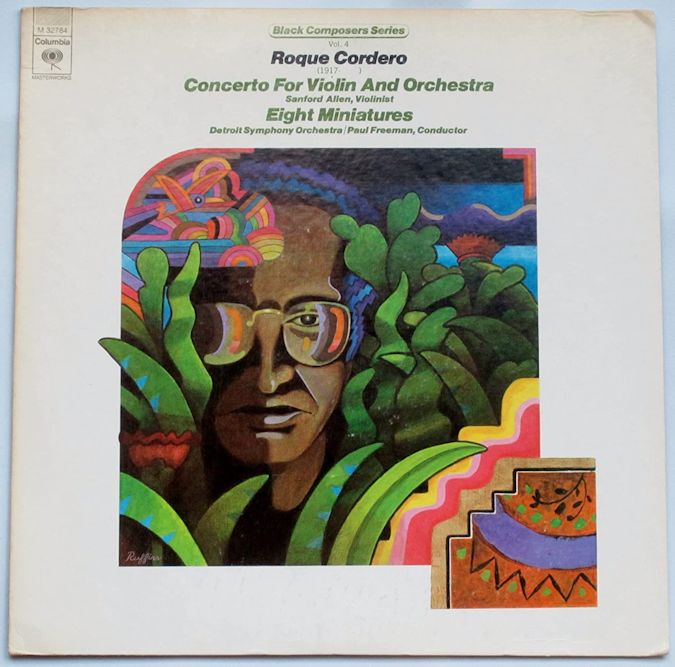

Roque Cordero

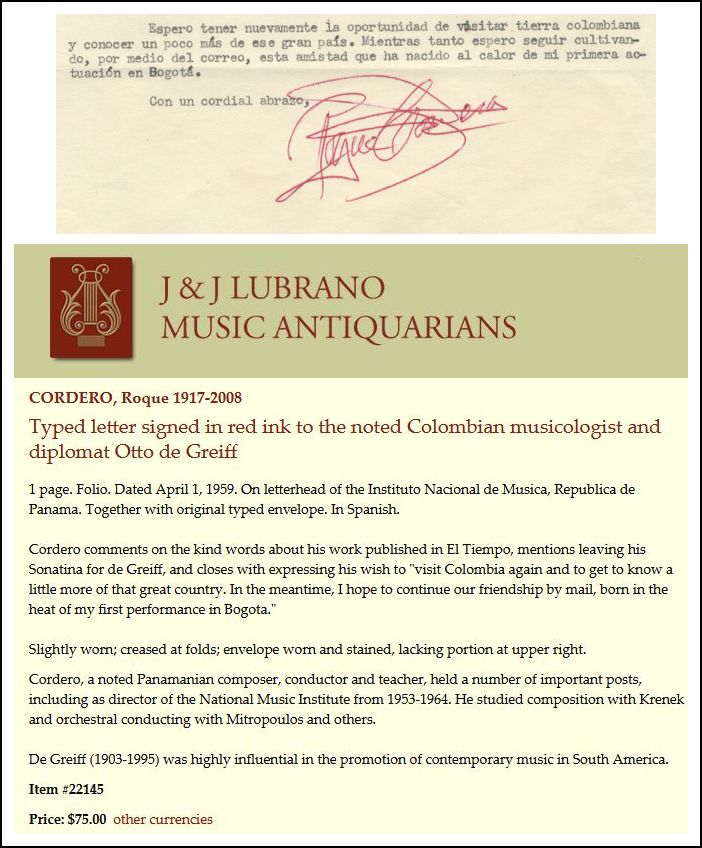

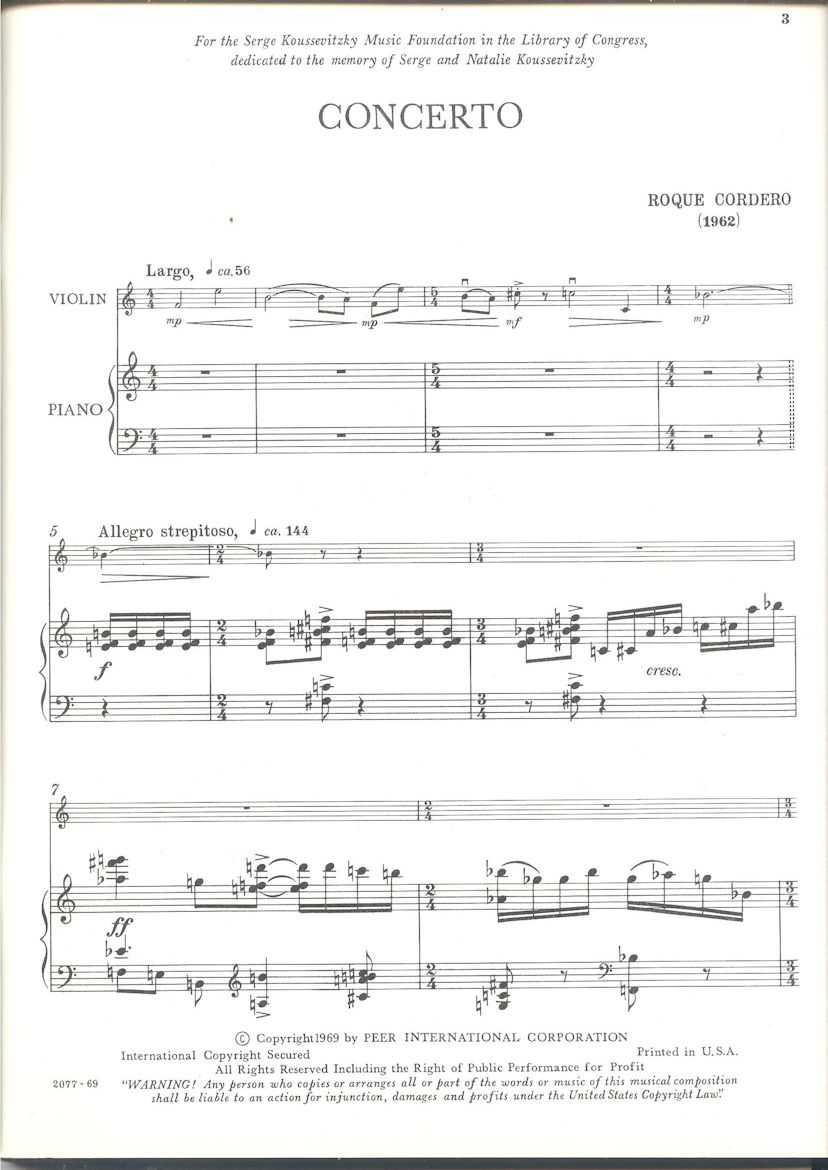

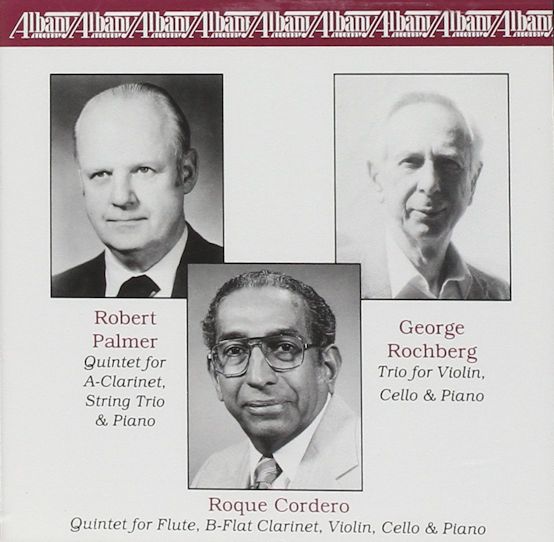

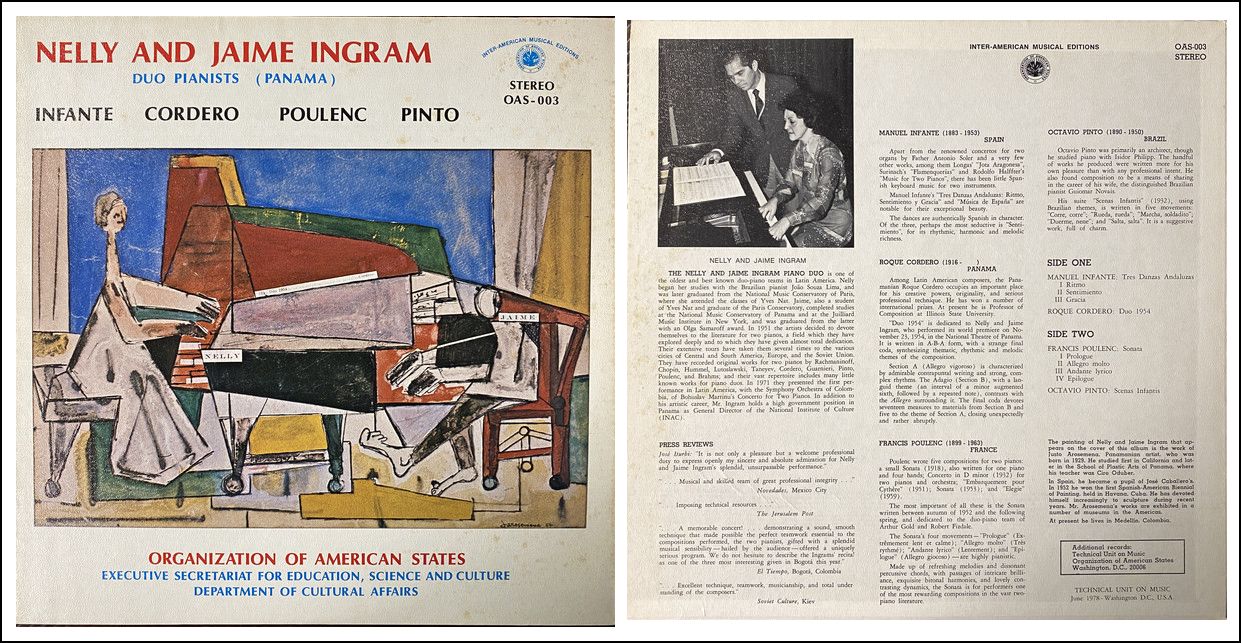

Roque CorderoBorn: August 16, 1917; Panama City, Panama Died: December 27, 2008; Dayton, OH His training began in Panama, where he was writing band pieces from an early age (he played clarinet in a fire brigade band from 1933). In 1943, he won a scholarship to the University of Minnesota, where he took conducting lessons from Dimitri Mitropoulos, who was impressed by Cordero's 1939 Capricho interiorano. While in Minnesota, he studied counterpoint and composition for four years with Ernst Krenek at Hamline University, from which he graduated in 1947. It was through Mitropoulos that Cordero met Krenek and the young Panamanian regarded Mitropoulos as a father figure. It was Mitropoulos who premiered Cordero's Panamanian Overture No. 2 with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra in 1946. After graduation, Cordero remained in America to study conducting at the Berkshire Music Center, and then in New York with Leon Barzin. In 1949, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship for composition and conducting. Back in Panama, he took a post as professor of composition at the National Conservatory (later called National Music Institute) from 1950 to 1964, serving as the school's director for most of that time. His work there greatly improved the quality of music instruction in Panama. The Institute granted the country's first degrees in music teaching and composition. His Curso de solfeo became the basis of music theory instruction through much of Latin America. Cordero was appointed conductor of the Panama National Orchestra in 1964, and in 1966, he returned to the United States to help run the Latin American Music Center at Indiana University (1966 - 1969), and then teach at Illinois State University in Normal (1972 - 1987). Cordero's earliest works are basically tonal and nationalist, rather in the style of the pre-serial Ginastera, but from 1946, under Krenek's influence, he employed a modified, Bergian twelve-tone technique, starting with his Sonatina for Violin and Piano. Even then, his music could allude to Latin American rhythms, as in the outer movements of the Sonatina, and the ostinato patterns of his one-movement Symphony No. 2. Furthermore, the angularity of Panamanian folk melodies lent itself naturally to a serial environment. Over the next years, his style remained consistent, although gradually favoring more irregular phrases, more complex rhythmic layering, and greater fascination with timbral effects. Unusually for a composer/conductor, Cordero's catalog is swollen with chamber music, especially for unusual combinations of instruments (such as his Permutaciones 7 for Clarinet, Trumpet, Timpani, Piano, Violin, Viola, and Bass). However, he produced many significant orchestral works, including four symphonies and concertos for piano, violin, and viola. == Biography adapted from James Reel's article

on the Allmusic websitte.

== Names and items which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews and articles elsewhere on my website. BD |

I tend not to go into detail about my own biography, but

in this instance, a bit of background is in order.

I tend not to go into detail about my own biography, but

in this instance, a bit of background is in order.

BD: You weren’t ready for it!

BD: You weren’t ready for it! Cordero: When I came to this country, the scholarship

was only for nine months. On March 18, 1943, I left my country.

I was supposed to be back before Christmas, but by luck, when the school

realized that I was a composer, and I also was a conductor, they invited

me to conduct the concert band at the university, with a concert march

that had won my prize (in 1937) in Panama [Reina de Amor].

The music critic of the Minneapolis Journal, John K. Sherman,

attended the concert, and was impressed by the music, and my conducting.

He came to see me, and said, “I suppose

that you have shown your music to Maestro Mitropoulos?”

[Dimitri Mitropoulos was Music Director of the Minneapolis Symphony

(now called the Minnesota Orchestra) from 1937-1949.] I said,

“No, I am not worthy. He’s

a big man. He won’t pay attention to me

knocking at the door. If somebody introduced me to him, perhaps he

will look at my music.” So, Sherman said,

“I will introduce you to him.”

That was April 19, 1943. I had been in this country for less than

one month. It was not until October 11 of the same year that he arranged

a meeting, a dinner with Mitropoulos in downtown Minneapolis. I

brought my Capricho and showed it to him, and that changed my life.

He asked me many questions about the piece. He praised the orchestration,

and said, “You must have very good teacher.”

I said, “Yes, I study the music of Beethoven,

and Brahms, and Tchaikovsky.” He said, “Those

are the best teachers.” I

had learned orchestration by myself. I taught myself how to read

music, too. When I started composing, I didn’t

know how to read music, although I was playing violin in the high school

orchestra. You could play it, and not read music. If you

had a good ear, you believe you are reading. [Laughs] Honestly,

you believe you are reading, but when I tried to write something, I could

play it myself, but my teacher could not read it. Then I taught

myself harmony so I could write the piano part. Yes, I am mostly

self-taught. Although I had some teachers later on tell me some

things, they could not push me as far as I wanted. Then Mitropoulos,

knowing that I was supposed to be going back in December, knew I really

wanted to be a composer. I was only 26. He said,

“You have four more years to become your own master.

After that, if you are not your own master, you should stop.”

So, if you are willing to stay here, and work for four years, I am willing

to pay all your expenses. You’re going

to study with Ernst Krenek... if he accepts you.”

Cordero: When I came to this country, the scholarship

was only for nine months. On March 18, 1943, I left my country.

I was supposed to be back before Christmas, but by luck, when the school

realized that I was a composer, and I also was a conductor, they invited

me to conduct the concert band at the university, with a concert march

that had won my prize (in 1937) in Panama [Reina de Amor].

The music critic of the Minneapolis Journal, John K. Sherman,

attended the concert, and was impressed by the music, and my conducting.

He came to see me, and said, “I suppose

that you have shown your music to Maestro Mitropoulos?”

[Dimitri Mitropoulos was Music Director of the Minneapolis Symphony

(now called the Minnesota Orchestra) from 1937-1949.] I said,

“No, I am not worthy. He’s

a big man. He won’t pay attention to me

knocking at the door. If somebody introduced me to him, perhaps he

will look at my music.” So, Sherman said,

“I will introduce you to him.”

That was April 19, 1943. I had been in this country for less than

one month. It was not until October 11 of the same year that he arranged

a meeting, a dinner with Mitropoulos in downtown Minneapolis. I

brought my Capricho and showed it to him, and that changed my life.

He asked me many questions about the piece. He praised the orchestration,

and said, “You must have very good teacher.”

I said, “Yes, I study the music of Beethoven,

and Brahms, and Tchaikovsky.” He said, “Those

are the best teachers.” I

had learned orchestration by myself. I taught myself how to read

music, too. When I started composing, I didn’t

know how to read music, although I was playing violin in the high school

orchestra. You could play it, and not read music. If you

had a good ear, you believe you are reading. [Laughs] Honestly,

you believe you are reading, but when I tried to write something, I could

play it myself, but my teacher could not read it. Then I taught

myself harmony so I could write the piano part. Yes, I am mostly

self-taught. Although I had some teachers later on tell me some

things, they could not push me as far as I wanted. Then Mitropoulos,

knowing that I was supposed to be going back in December, knew I really

wanted to be a composer. I was only 26. He said,

“You have four more years to become your own master.

After that, if you are not your own master, you should stop.”

So, if you are willing to stay here, and work for four years, I am willing

to pay all your expenses. You’re going

to study with Ernst Krenek... if he accepts you.” BD: You have to have the burning desire in the heart.

BD: You have to have the burning desire in the heart. BD: Twenty years later.

BD: Twenty years later.[At this point, I turned over the cassette to continue recording our conversation.]

BD: But they don’t

have to.

BD: But they don’t

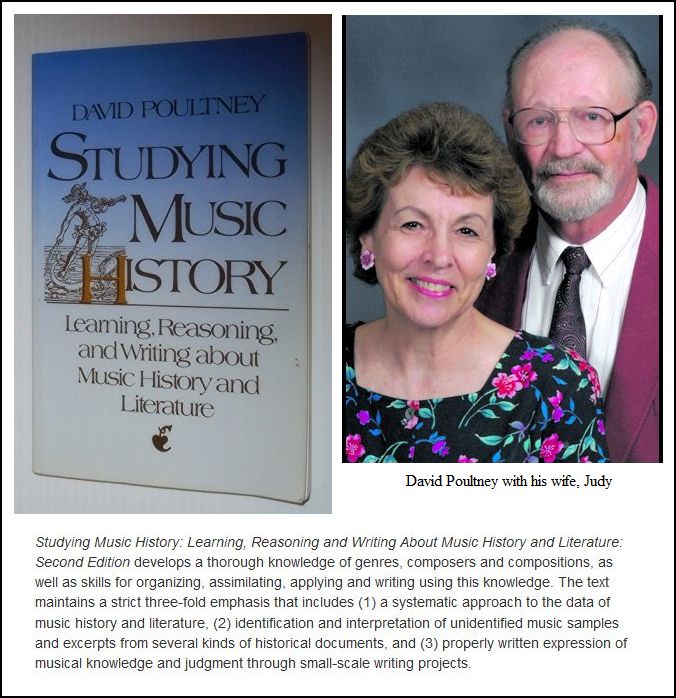

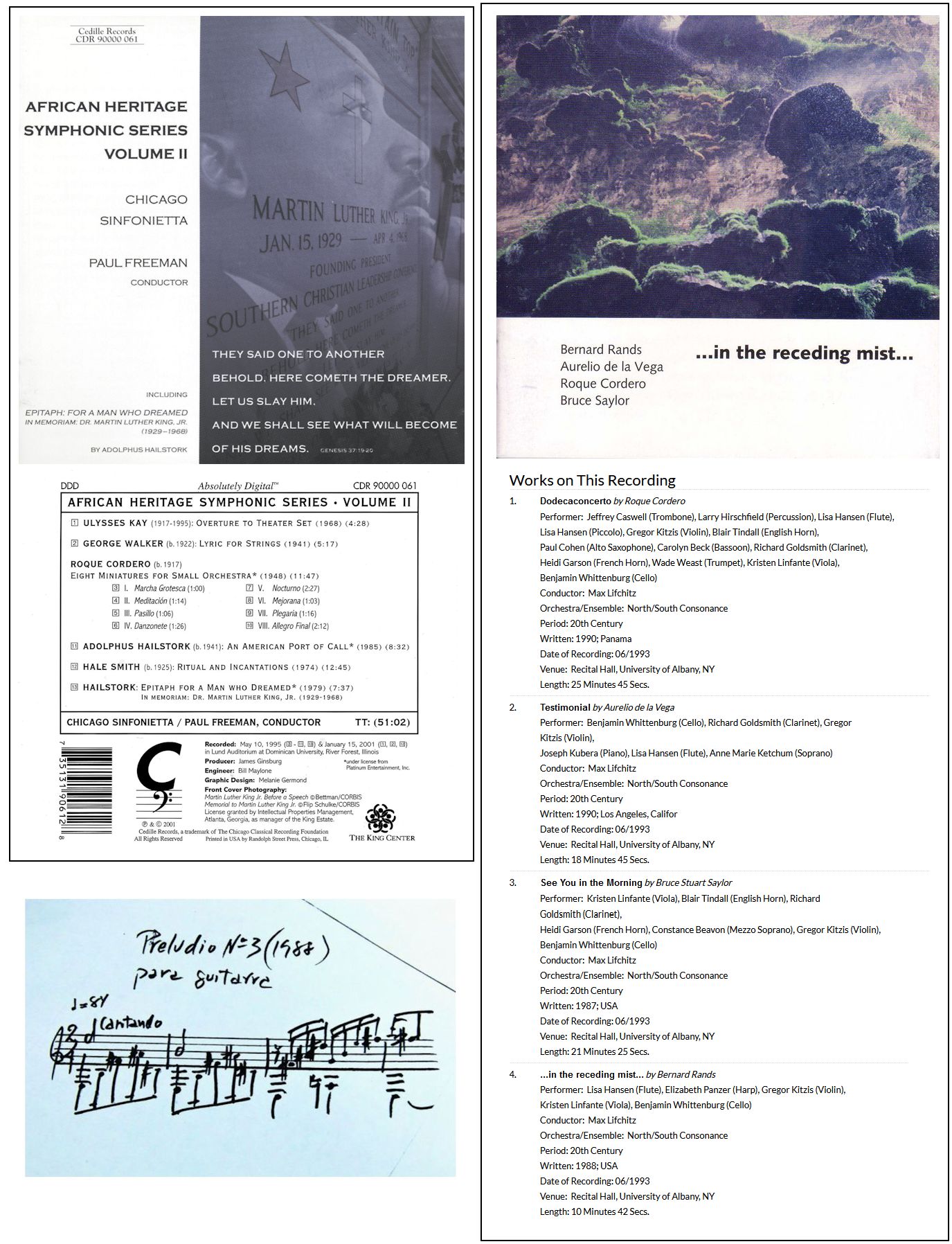

have to. Cordero: Yes. The Louisville Orchestra played it

at that time, and then they decided to record it. Before that, my

publisher decided to publish the score, knowing that he wasn’t

going to make any money with it, because of expenses. Just the

engraving alone is $2,000. But he had some extra money at that moment,

and said to me, “Roque, I am going to publish

this, and I will send it to all the orchestras of the land.”

He sent that to all the orchestras with a letter of presentation.

This was not only to the big orchestras, because when I came to Illinois

State in 1972, I went to a concert of the Bloomington-Normal Symphony.

I introduced myself to the conductor [Bernard Goodman, who conducted

the Bloomington-Normal Symphony from 1971 to 1974], and he was

surprised. “What are you doing here?”

he asked, and I said, “I just moved here.”

“I thought you were in New York because I just

received your symphony.” But he never played

it. It’s in the library of all the orchestras,

even small ones like that, but no conductors have ever looked at it,

because the name ‘Cordero’

doesn’t mean anything to them. So, the

piece hasn’t been played. [Pauses a moment]

I tried to get Mr.

Solti [Music Director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra from 1969

to 1991] interested in my music. They arranged a meeting, so

I went to Chicago. That night they were playing a clarinet concerto

by Mr. Corigliano,

who had just been appointed as composer-in-residence. The concerto

was excellent, and when I was going down to meet Maestro Solti, I stopped

Mr. Corigliano, and congratulated him. Then I was taken to meet

Maestro Solti. We spoke for thirty seconds, and we had to leave.

He said I could send the music to him. I don’t

like to be sending music that I know is going to be put in a corner.

So I wrote back to him later on, reminding him that we had met.

My idea was to show him my most ambitious work, the Cantata for Peace

[Cantata para la Paz (1979)], which was one of the Bicentennial

Commissions of the National Endowment for the Arts. It was written

to the memory of four men who spoke of peace, and were victims of violence

— Abraham Lincoln, Mahatma Gandhi, John F. Kennedy,

and Martin Luther King, Jr. It is really in the memory of all men,

women and children who die in the name of peace. I wrote my own

text. I didn’t want to quote from any of

the four men, although I read their writings, and I found that we have

the ideal of peace in common. So I created my own text

in Spanish, but there is also an English setting done by my wife.

She’s a musician, so she could really get the

music, and write the English translation to fit the music.

Cordero: Yes. The Louisville Orchestra played it

at that time, and then they decided to record it. Before that, my

publisher decided to publish the score, knowing that he wasn’t

going to make any money with it, because of expenses. Just the

engraving alone is $2,000. But he had some extra money at that moment,

and said to me, “Roque, I am going to publish

this, and I will send it to all the orchestras of the land.”

He sent that to all the orchestras with a letter of presentation.

This was not only to the big orchestras, because when I came to Illinois

State in 1972, I went to a concert of the Bloomington-Normal Symphony.

I introduced myself to the conductor [Bernard Goodman, who conducted

the Bloomington-Normal Symphony from 1971 to 1974], and he was

surprised. “What are you doing here?”

he asked, and I said, “I just moved here.”

“I thought you were in New York because I just

received your symphony.” But he never played

it. It’s in the library of all the orchestras,

even small ones like that, but no conductors have ever looked at it,

because the name ‘Cordero’

doesn’t mean anything to them. So, the

piece hasn’t been played. [Pauses a moment]

I tried to get Mr.

Solti [Music Director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra from 1969

to 1991] interested in my music. They arranged a meeting, so

I went to Chicago. That night they were playing a clarinet concerto

by Mr. Corigliano,

who had just been appointed as composer-in-residence. The concerto

was excellent, and when I was going down to meet Maestro Solti, I stopped

Mr. Corigliano, and congratulated him. Then I was taken to meet

Maestro Solti. We spoke for thirty seconds, and we had to leave.

He said I could send the music to him. I don’t

like to be sending music that I know is going to be put in a corner.

So I wrote back to him later on, reminding him that we had met.

My idea was to show him my most ambitious work, the Cantata for Peace

[Cantata para la Paz (1979)], which was one of the Bicentennial

Commissions of the National Endowment for the Arts. It was written

to the memory of four men who spoke of peace, and were victims of violence

— Abraham Lincoln, Mahatma Gandhi, John F. Kennedy,

and Martin Luther King, Jr. It is really in the memory of all men,

women and children who die in the name of peace. I wrote my own

text. I didn’t want to quote from any of

the four men, although I read their writings, and I found that we have

the ideal of peace in common. So I created my own text

in Spanish, but there is also an English setting done by my wife.

She’s a musician, so she could really get the

music, and write the English translation to fit the music.

© 1989 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at Illinois State University in Normal, Illinois, on August 30, 1989. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following November. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to David Badagnani for his help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.