|

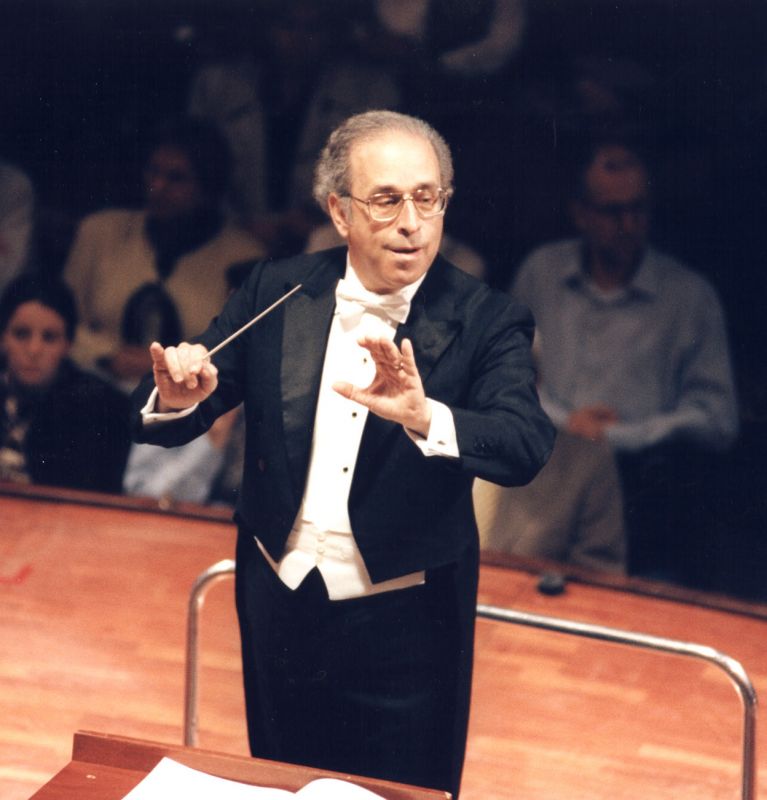

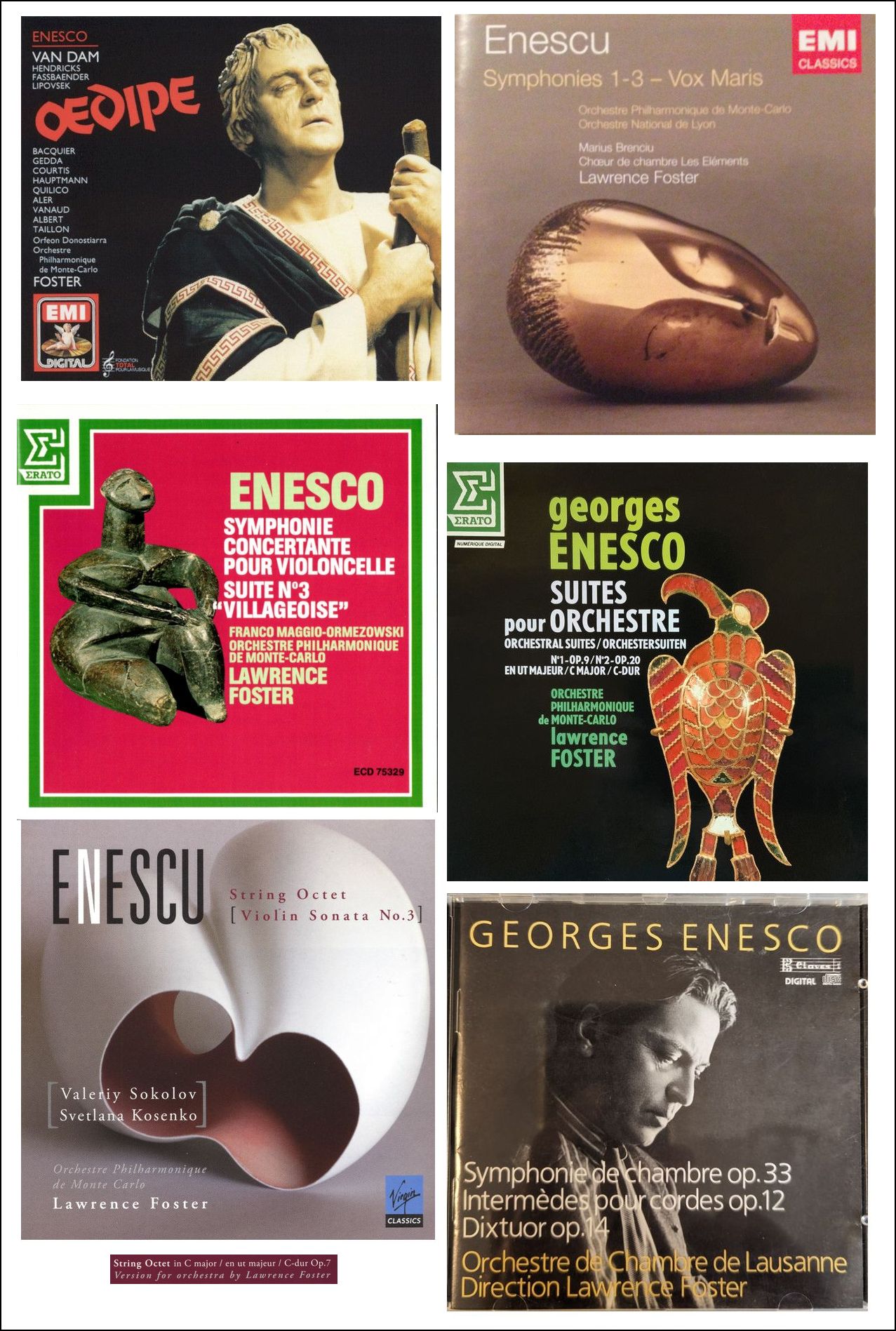

Lawrence Foster (born October 23, 1941) is an American conductor of Romanian ancestry. He was born in Los Angeles, California, to Romanian parents. His father died when Foster was three years old. He was later adopted by his stepfather which is why the last name is not traditionally Romanian. Foster studied conducting with German conductor Fritz Zweig and piano with Joanna Grauden, both in Los Angeles. His other teachers and mentors have included: Karl Böhm, Bruno Walter, Henry Lewis, and Franz Waxman. Foster became the conductor of the San Francisco Ballet at the age of 18, and served as assistant conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic under Zubin Mehta. He was awarded the Koussevitzky Conducting Prize at Tanglewood in 1966. In 1969 he was named chief guest conductor of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in London. He has held music directorships with the Houston Symphony, the Ojai Music Festival, the Monte-Carlo Philharmonic Orchestra, the Duisburg Philharmonic, the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra, and the Barcelona Symphony Orchestra and National Orchestra of Catalonia, among others. In 1990, Foster was appointed music director of the Aspen Music Festival and School. From 2002 to 2013, Foster was the music director of the Gulbenkian Orchestra of Lisbon, Portugal. He also served as music director of the Orchestre National de Montpellier and the Opéra National de Montpellier from 2009 to 2012. Foster was music director of Opéra de Marseille and the Orchestre philharmonique de Marseille from 2012 to 2023. From 2019 to 2023, Foster was artistic director and chief conductor of the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra (NOSPR). Foster is particularly noted as an interpreter of the works of George Enescu, and has made a comprehensive survey of commercial recordings of Enescu's music [which are shown at the bottom of this webpage]. He served as artistic director of the George Enescu Festival from 1998 to 2001. In 2003, Foster was decorated by the President for services to Romanian music. In 2023, Foster was awarded the Romanian National Order of Merit,

Commander, for his contribution to Romanian culture and promotion of the

music of Enescu. His

recording of Enescu's Oedipe was awarded the Grand Prix du Disque

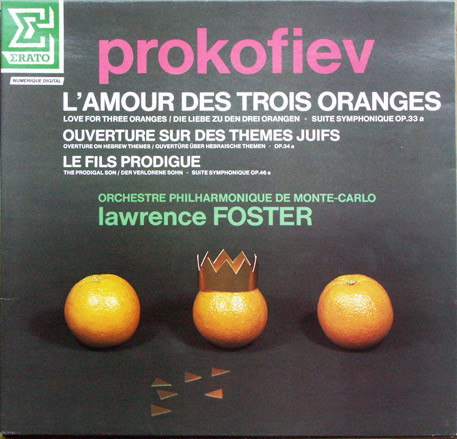

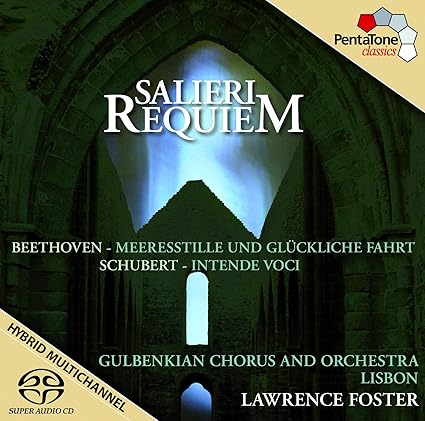

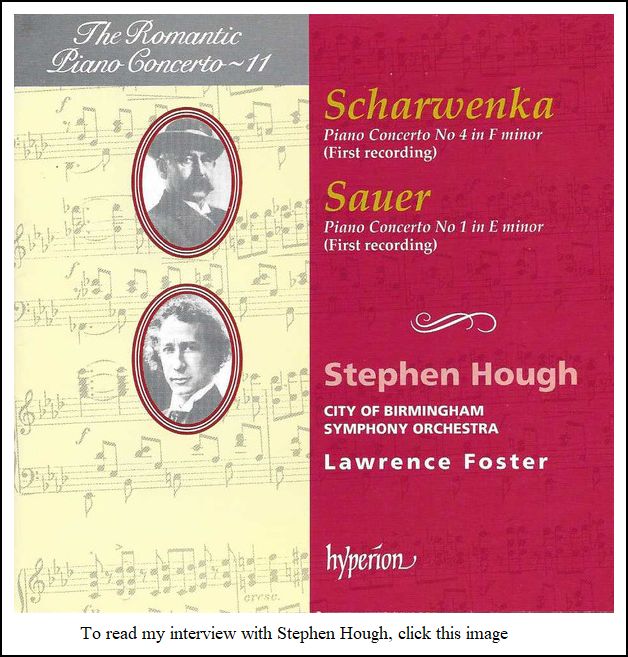

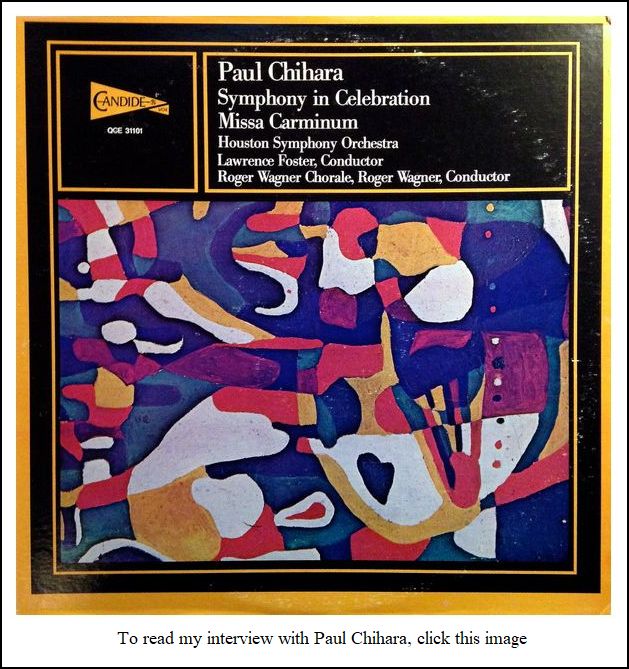

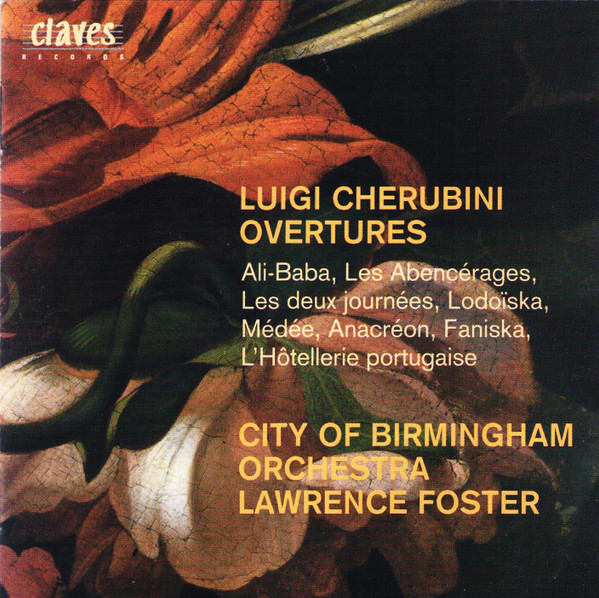

from the Académie Charles Cros in France. == Foster has made many recordings on various

labels, and just a few are used as illustrations on this webpage.

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

Walter Felsenstein (30 May 1901 – 8 October 1975) was an Austrian

theater and opera director. He was one of the most important

exponents of textual accuracy, and gave productions in which dramatic

and musical values were exquisitely researched and balanced.

In 1947 he created the Komische Oper in East Berlin, where he worked

as director until his death.

Walter Felsenstein (30 May 1901 – 8 October 1975) was an Austrian

theater and opera director. He was one of the most important

exponents of textual accuracy, and gave productions in which dramatic

and musical values were exquisitely researched and balanced.

In 1947 he created the Komische Oper in East Berlin, where he worked

as director until his death. Preparations for each new production could last two months or longer. If singers meticulously coached and trained in their parts fell ill, performances were simply canceled. Since the glamorous superstars of the day could never spare the time Felsenstein required, he worked with his own hand-picked troupe of devoted singers, most from Eastern Europe and virtually unknown in the West. Everything was sung in German, usually in his own translations. Whoever wanted to experience this singular operatic mix had to make the pilgrimage to East Berlin, a trip that became even dicier after the wall went up. Together with the Komische Oper troupe he visited the USSR a few times. In Moscow it was stated that his way of the opera staging was similar to the principles of Konstantin Stanislavsky. His most famous students were Götz Friedrich and Harry Kupfer, both of whom went on to have important careers developing Felsenstein's work. |

| Marius Constant (February 7, 1925 –

May 15, 2004) was a Romanian-born French composer and conductor. Although

known in the classical world primarily for his ballet scores, his most

widely known music was the iconic theme for The Twilight Zone American

television series. Constant was born in Bucharest, Romania, and studied piano and composition at the Bucharest Conservatory, receiving the George Enescu Award in 1944. In 1946, he moved to Paris, studying at the Conservatoire de Paris with Olivier Messiaen, Tony Aubin, Arthur Honegger and Nadia Boulanger. His compositions earned several prizes, including the Prix Italia in 1952 for Le joueur de flûte. From 1950 on, he was increasingly involved with electronic music, and joined Pierre Schaeffer's Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète.

For the 1957 Aix-en-Provence Festival, he wrote a piano concerto, but won wider recognition for the premiere, conducted by Leonard Bernstein, of 24 Préludes pour Orchestre (1958). In the late 1950s, Constant was commissioned by Lud Gluskin of CBS to create a number of short pieces for the CBS stock music library that could be used in CBS radio and TV shows. The unusual, sometimes discordant nature of Constant's work meant that the pieces were seldom heard or used. In 1960, Gluskin was asked to find a new theme for the main title and end credits of the CBS television series The Twilight Zone, then entering its second season, to replace the original one by Bernard Herrmann. New pieces submitted by Herrmann, Jerry Goldsmith, Leith Stevens, and others, were considered unsuitable. In desperation, Gluskin edited together two pieces by Constant ("Étrange No. 3", a series of repeated four-note phrases on electric guitar, and "Milieu No. 2", an odd pattern of guitar notes, bongo drums, brass and flutes). The resulting theme quickly became iconic, and is easily Constant's most well-known work. Constant himself was apparently unaware for some years that his music was being used as The Twilight Zone theme. Because the music was part of a "work made for hire" agreement with CBS, Constant derived no ongoing income from it. In 1970, he took over the musical direction of the ORTF [French National Radio and Television]. From 1973 to 1978 he directed at the Paris Opera, and in 1988 and 1989 was Professor of Orchestration at the Paris Conservatory. Besides these appointments, he taught at Stanford University and in Hilversum. La tragédie de Carmen (1981), his adaptation of Bizet's opera for director Peter Brook, was an international success. * * *

* *

Interestingly, in my interview with the great French vocal and diction coach Janine Reiss, the name Dukas came up, and I received a brief lesson... BD: Is there a line from Lully through half a dozen other composers, to Massenet, to Charpentier, to Boulez? Janine Reiss: I’m afraid I don’t think there is a line from Lully. That’s very strange. For the others, yes. There is a line, not a direct line but there is something in common between Massenet, Charpentier, Rousseau, Bizet, Saint-Saëns, Roussel, Pierne, more or less. BD: Ducasse? [At this point I got a lesson in exact pronunciation. I had said doo-KASS, but meant Paul Dukas.] JR: Ducasse, more or less. Roger Ducasse [doo-KASS] and Paul Dukas [doo-KAH]. BD: [Very grateful for this instruction] I see... Pourquoi? [Why?] JR: C’est la question que n'est jamais fait. [This is a question which is never asked!] [Both burst out laughing] If you say ‘pourquoi’ to a French, ‘le pays de la logique’ [the country of logic], he will reply, ‘Il est pêchu!’ [It’s peachy!] [More laughter] Generally when an ‘s’ comes after an ‘a’, it darkens the ‘a’. I’ll give an example. In the old French, an hôtel was an ‘hostelerie’ [hostelry], and it has become hôtel. BD: [Since we were speaking and not writing] With a circumflex? JR: With a circumflex, which means that the ‘o’ is darkened. Instead of ‘hôtel’ [pronounced like hot] it’s ‘hôtel’ [pronounced like note], and the ‘s’ disappeared. So for Paul Dukas, it’s not Dukas [pronounced like cat] but Dukas [pronounced like car] because of the ‘s’ which remains, but it’s the old spelling of the name. For a name it’s rare that the spelling changes. |

See my interviews with Brigitte Fassbaender,

and John Aler

© 1994 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 7, 1994. Portions were broadcast on WNIB five days later, and again in 1996. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.