JR: Yes. The only thing I’m sorry about is

that the time is really too short. In fact the week is not a week,

it’s just five days. I got here Sunday night and I started Monday morning

at 9 AM. I have got nine females to work with, and it’s just too short.

I’m not accustomed to that kind of short time to devote to every singer.

Generally if I work privately, I give one hour, which is never one hour.

It is always something like eighty minutes for one hour. So it’s very

difficult because I’ve got a lot to do.

JR: Yes. The only thing I’m sorry about is

that the time is really too short. In fact the week is not a week,

it’s just five days. I got here Sunday night and I started Monday morning

at 9 AM. I have got nine females to work with, and it’s just too short.

I’m not accustomed to that kind of short time to devote to every singer.

Generally if I work privately, I give one hour, which is never one hour.

It is always something like eighty minutes for one hour. So it’s very

difficult because I’ve got a lot to do.  BD: So this is the individual genius of the interpreter?

BD: So this is the individual genius of the interpreter? JR: Well, Japanese, German, American, English,

Italian, they all are different. But what I can tell you undoubtedly

is that generally speaking the singers with whom I get the best result are

the Anglo-Americans for many reasons. First of all there is the training.

They know what is hard work. The first time I had the opportunity to

work with Anglo-Saxon singers, I understood that the best singers had been

trained like sportsmen. They realize that the singer is not only a

pair of vocal cords.

JR: Well, Japanese, German, American, English,

Italian, they all are different. But what I can tell you undoubtedly

is that generally speaking the singers with whom I get the best result are

the Anglo-Americans for many reasons. First of all there is the training.

They know what is hard work. The first time I had the opportunity to

work with Anglo-Saxon singers, I understood that the best singers had been

trained like sportsmen. They realize that the singer is not only a

pair of vocal cords.

BD: Are most of the well-known singers receptive

to your kind of coaching?

BD: Are most of the well-known singers receptive

to your kind of coaching? BD: I just wondered because he was writing for such

a certain prescribed fashion, and if that fashion is now not used at all,

is his music lost?

BD: I just wondered because he was writing for such

a certain prescribed fashion, and if that fashion is now not used at all,

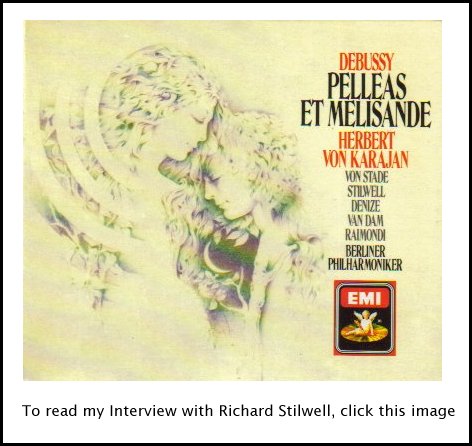

is his music lost? JR: Everything, everything! And above

all Pelléas et Mélisande,

which now, if I had to choose only one opera, I would take that one.

Before I started coaching Pelléas

et Mélisande and working on it for recording or anything like

that, I was almost reluctant because I knew I was going to suffer, and nobody

likes to suffer. So I’m very much conscious of that. It’s a kind

of reluctance even on my flesh, on my body because I love that work so much

that it’s a kind of ‘sofferenza’.

JR: Everything, everything! And above

all Pelléas et Mélisande,

which now, if I had to choose only one opera, I would take that one.

Before I started coaching Pelléas

et Mélisande and working on it for recording or anything like

that, I was almost reluctant because I knew I was going to suffer, and nobody

likes to suffer. So I’m very much conscious of that. It’s a kind

of reluctance even on my flesh, on my body because I love that work so much

that it’s a kind of ‘sofferenza’. JR: No. It matters just if you can reach

the high notes. If you can’t, you shouldn’t sing the part. But

he’s got to have a natural genuine poetry, part of dream, a real distinction;

something raffiné [refined].

That’s something you can’t teach. That’s something you can’t give.

That’s something you can’t bring to somebody.

JR: No. It matters just if you can reach

the high notes. If you can’t, you shouldn’t sing the part. But

he’s got to have a natural genuine poetry, part of dream, a real distinction;

something raffiné [refined].

That’s something you can’t teach. That’s something you can’t give.

That’s something you can’t bring to somebody. BD: Plasson mentioned Serge Nigg.

BD: Plasson mentioned Serge Nigg. BD: Is Purcell the same school as Lully?

BD: Is Purcell the same school as Lully? BD: [Laughs] It was too much of a dilemma?

BD: [Laughs] It was too much of a dilemma?

|

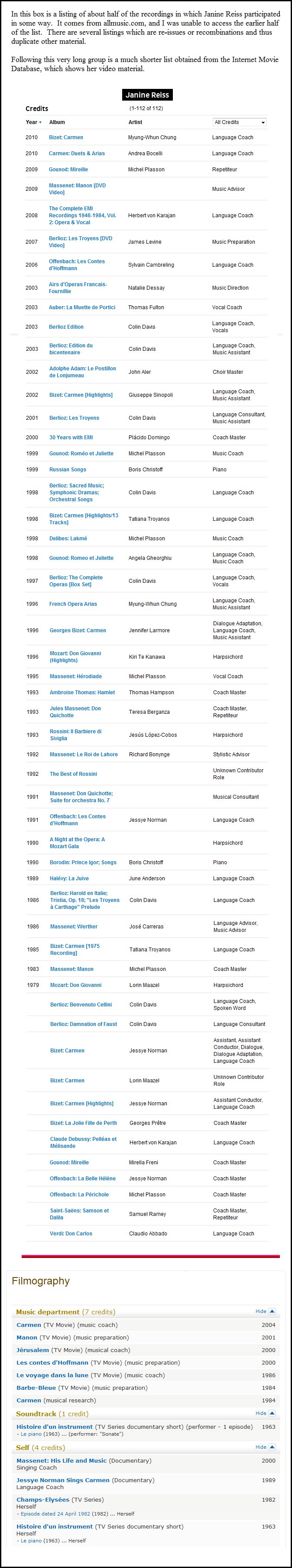

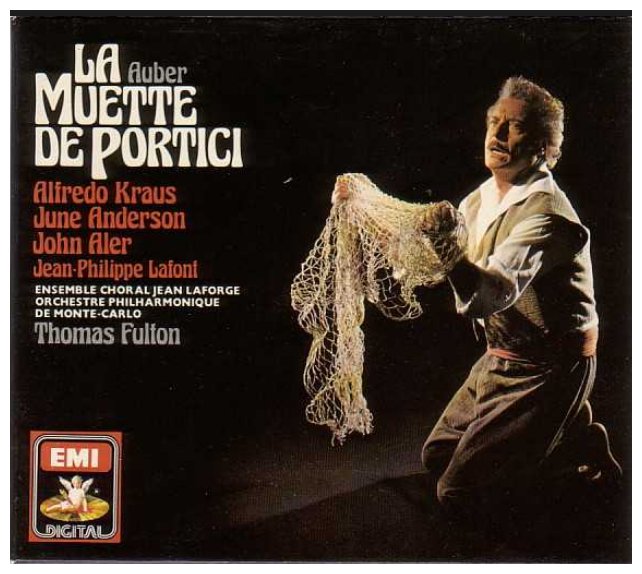

To read my Interview with John Aler, click HERE.

To read my Interviews with Jennifer Larmore, click HERE. To read my Interview with Thomas Moser, click HERE. To read my Interview with Giuseppe Sinopoli, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Jon Vickers, click HERE. To read my Interview with Ryland Davies, click HERE. To read my Interview with Anne Howells, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Jesús López-Cobos, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Sutherland and Bonynge, click HERE. To read my Interviews with Sherrill Milnes, click HERE. To read my Interviews with Nicolai Ghiaurov, click HERE. == == == == == From the box at left, there are two other names which have been my Interview guests... Tatiana Troyanos, HERE Thomas Hampson, HERE |

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in the studios of WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago on July 21, 1982. A few quotes were used in Opera Scene magazine the following November. Portions were broadcast (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1988, 1990 and 1996. A copy of the unedited audio was given to De Paul University. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website early in 2015. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.