LH: Well, it has happened to me quite a bit.

I’m fortunate — or unfortunate — in

being a very quick study, and so quite often these things happen to me.

But anyway, it went very well actually. There was so much adrenaline

in my system by then. It really went very well, and this marvelous

collaboration began. I have to say I would come and sing with Music

of the Baroque anytime because I’m a great, great fan of the group.

It’s absolutely sensational. I believe that this chorus is today’s

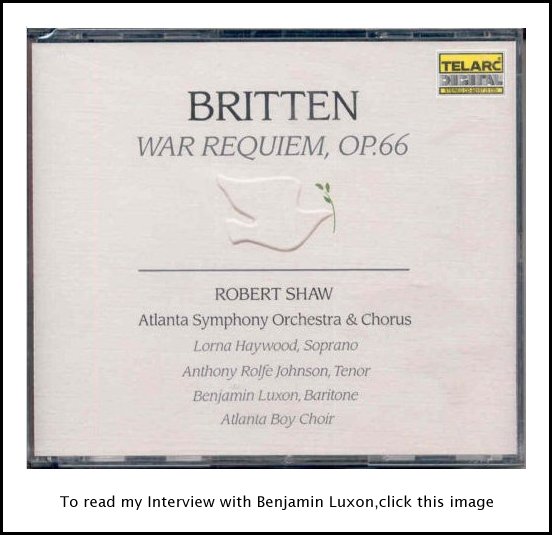

equivalent of the Robert

Shaw Chorale, which of course was a chorale par excellence. It

doesn’t exist anymore. Mr. Shaw has the Atlanta Symphony and the Chorus,

but the Chorale itself of course doesn’t exist anymore. This is the

closest thing to that; absolute perfection, and I never cease to be amazed.

Each time I come it seems to get better and better and better, and it’s introduced

me to a great number of Handel’s works that I otherwise would probably not

have heard of, let alone sung.

LH: Well, it has happened to me quite a bit.

I’m fortunate — or unfortunate — in

being a very quick study, and so quite often these things happen to me.

But anyway, it went very well actually. There was so much adrenaline

in my system by then. It really went very well, and this marvelous

collaboration began. I have to say I would come and sing with Music

of the Baroque anytime because I’m a great, great fan of the group.

It’s absolutely sensational. I believe that this chorus is today’s

equivalent of the Robert

Shaw Chorale, which of course was a chorale par excellence. It

doesn’t exist anymore. Mr. Shaw has the Atlanta Symphony and the Chorus,

but the Chorale itself of course doesn’t exist anymore. This is the

closest thing to that; absolute perfection, and I never cease to be amazed.

Each time I come it seems to get better and better and better, and it’s introduced

me to a great number of Handel’s works that I otherwise would probably not

have heard of, let alone sung. Florence Kopleff (May 2, 1924 in NYC - July 24, 2012 in Atlanta, GA) began

her career in 1941 when she was in her senior year of high school. In 1954

The New York Times termed

her performance at New York's Town Hall "a debut recital of considerable

distinction," and further stated that "Her voice is a large, powerful instrument

with a wonderful ringing sonority, evenly produced over a wide range." She

was very active as a concert and oratorio singer, appearing and recording

with many of the great conductors of her era, particularly as a soloist with

the Robert Shaw Chorale. Time magazine

once called her the "greatest living alto."

Florence Kopleff (May 2, 1924 in NYC - July 24, 2012 in Atlanta, GA) began

her career in 1941 when she was in her senior year of high school. In 1954

The New York Times termed

her performance at New York's Town Hall "a debut recital of considerable

distinction," and further stated that "Her voice is a large, powerful instrument

with a wonderful ringing sonority, evenly produced over a wide range." She

was very active as a concert and oratorio singer, appearing and recording

with many of the great conductors of her era, particularly as a soloist with

the Robert Shaw Chorale. Time magazine

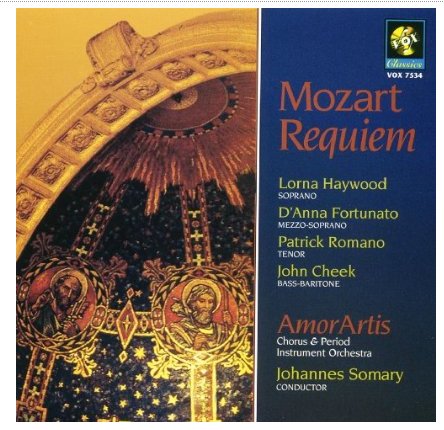

once called her the "greatest living alto."She taught at Georgia State University starting in 1968, when she became a professor and the school's first artist-in-residence. The GSU School of Music's recital hall is named for her. Her recordings include... Bach: Mass in B minor with Robert Shaw, RCA Victor, Grammy winner, 1961. Beethoven: 9th Symphony with Chicago Symphony and Fritz Reiner, Phyllis Curtin, John McCollum, Donald Gramm, RCA Victor. Berlioz: L'Enfance du Christ, with Boston Symphony and Charles Münch, Cesare Valletti, Giorgio Tozzi, Gerard Souzay, RCA Victor. Also a 1966 video of a live performance, again with the Boston Symphony conducted by Munch, with John McCollum, Donald Gramm, Theodor Uppman, VAI. Mahler: Symphony No. 2 with Utah Symphony and Maurice Abravanel, Beverly Sills, Vanguard. Handel: Messiah with Robert Shaw, RCA Victor, Grammy winner, 1967. |

BD: Is that a mistake?

BD: Is that a mistake? LH: I saw a production of Measure for Measure this summer, and

it’s exactly the same predicament. The sister goes to plead for the

life of her brother, and the person in authority says, “I

will spare your brother’s life if you surrender yourself to me.”

She refuses, and she says she would rather have her brother lose his life.

You could hear an audible groan from the audience at that point. It

was such a brilliant production that they ultimately pulled it off, but

there is that modern reaction to things like that. At least in Theodora there are many more religious

connotations that get people’s sympathies, and allow that to be accepted

in some way.

LH: I saw a production of Measure for Measure this summer, and

it’s exactly the same predicament. The sister goes to plead for the

life of her brother, and the person in authority says, “I

will spare your brother’s life if you surrender yourself to me.”

She refuses, and she says she would rather have her brother lose his life.

You could hear an audible groan from the audience at that point. It

was such a brilliant production that they ultimately pulled it off, but

there is that modern reaction to things like that. At least in Theodora there are many more religious

connotations that get people’s sympathies, and allow that to be accepted

in some way.  BD: Do you like making records?

BD: Do you like making records? LH: I expect them to get there in time to

read the program notes, and to have done a little bit of homework as to

the plot so they have just a skeleton idea of what actually takes place

in the opera or in the oratorio. There’s a lot of criticism of how

to get taught singing in English. There’s a lot of criticism leveled

for poor diction while singing in English, their own language. There’s

a lot of snobbery that goes on, “I’d much prefer to

hear it in the original language!” Having done

a little bit of research on it, it’s my experience that people who prefer

to hear it in the original language do not speak that original language

at all. Some of them have a smattering, but there are very few people

who are really fluent in those languages. They are prepared to sit

back and just listen to it in French, Italian, German, whatever, and think

that it’s just wonderful. It’s as if they can hear every single word

and understand every single word. They can’t, and they don’t!

However when the language is English, which they speak and should understand,

they feel a sudden irritation because the fact that it is in their own language

puts an extra burden on them. They have to listen carefully in an

attempt to get it all. They can’t help themselves, but they do try

to catch every word, and that irritates them. They can’t just sit back

and ‘be entertained’.

LH: I expect them to get there in time to

read the program notes, and to have done a little bit of homework as to

the plot so they have just a skeleton idea of what actually takes place

in the opera or in the oratorio. There’s a lot of criticism of how

to get taught singing in English. There’s a lot of criticism leveled

for poor diction while singing in English, their own language. There’s

a lot of snobbery that goes on, “I’d much prefer to

hear it in the original language!” Having done

a little bit of research on it, it’s my experience that people who prefer

to hear it in the original language do not speak that original language

at all. Some of them have a smattering, but there are very few people

who are really fluent in those languages. They are prepared to sit

back and just listen to it in French, Italian, German, whatever, and think

that it’s just wonderful. It’s as if they can hear every single word

and understand every single word. They can’t, and they don’t!

However when the language is English, which they speak and should understand,

they feel a sudden irritation because the fact that it is in their own language

puts an extra burden on them. They have to listen carefully in an

attempt to get it all. They can’t help themselves, but they do try

to catch every word, and that irritates them. They can’t just sit back

and ‘be entertained’. BD: What really is Rock music?

BD: What really is Rock music?

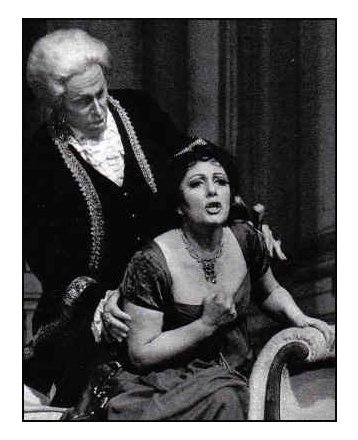

LH: Yes, right! It’s insulting anyway to

expect people to spoon-feed you these things. If it’s you that’s going

to be out there, it’s you that should do the basic work. Then you gather

from other people’s expertise. He taught me that when the curtain

goes up it is at a certain moment in time. It just happens to go up

at that moment in time. Before the curtain goes up, things have already

been going on, and when the curtain comes down, life continues. It

just happens to go up and down at those two moments. So there is a

flow of action that starts before the curtain goes up and continues after

the curtain is down. You need to learn big things about your own character

before you appear. You listen to what people say about you for big

clues. For instance, you learn a lot about Tosca before she ever shows

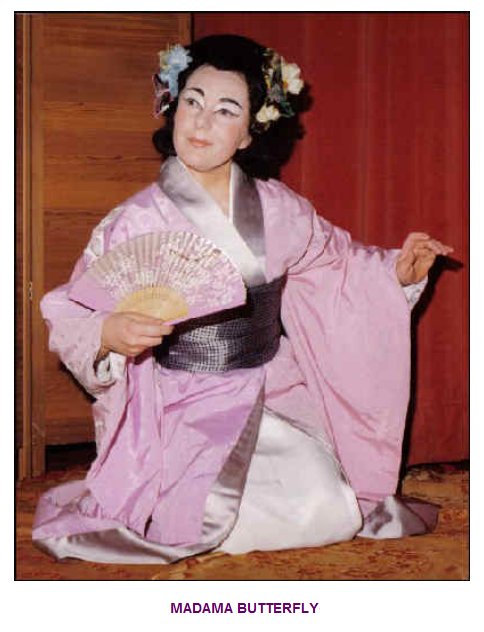

her face. You learn a lot about Butterfly by listening to the conversation

between Pinkerton and Sharpless. Those are big clues, and so to learn

only your part is pretty stupid. The only way you can get a complete

round character is by eavesdropping. You might think that if you’re

that person you wouldn’t be there to hear that conversation, but the point

is that you are two people. You are the character that you are portraying

but you’re also the artist doing the portraying. So you have to know

these things.

LH: Yes, right! It’s insulting anyway to

expect people to spoon-feed you these things. If it’s you that’s going

to be out there, it’s you that should do the basic work. Then you gather

from other people’s expertise. He taught me that when the curtain

goes up it is at a certain moment in time. It just happens to go up

at that moment in time. Before the curtain goes up, things have already

been going on, and when the curtain comes down, life continues. It

just happens to go up and down at those two moments. So there is a

flow of action that starts before the curtain goes up and continues after

the curtain is down. You need to learn big things about your own character

before you appear. You listen to what people say about you for big

clues. For instance, you learn a lot about Tosca before she ever shows

her face. You learn a lot about Butterfly by listening to the conversation

between Pinkerton and Sharpless. Those are big clues, and so to learn

only your part is pretty stupid. The only way you can get a complete

round character is by eavesdropping. You might think that if you’re

that person you wouldn’t be there to hear that conversation, but the point

is that you are two people. You are the character that you are portraying

but you’re also the artist doing the portraying. So you have to know

these things. This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 13, 1985. Portions were broadcast on WNIB two days later. This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.