|

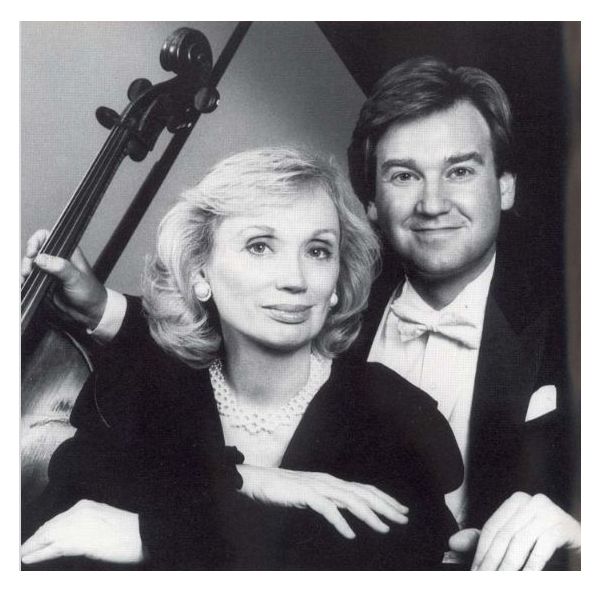

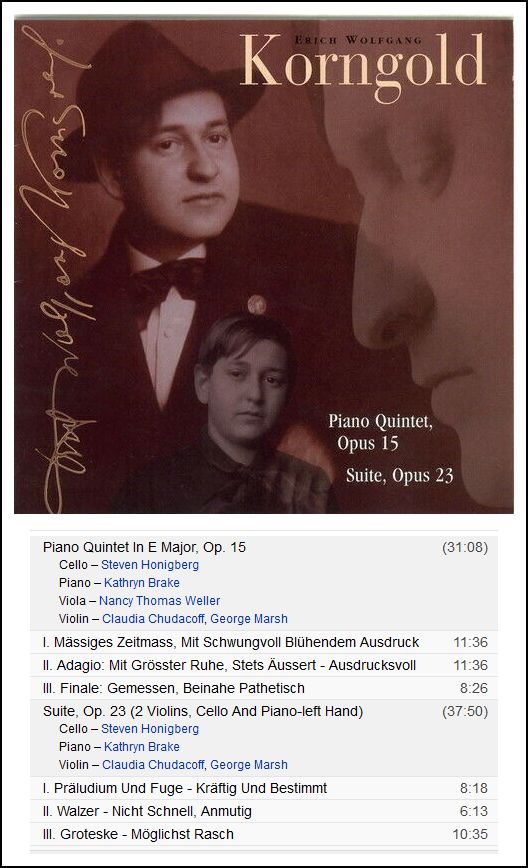

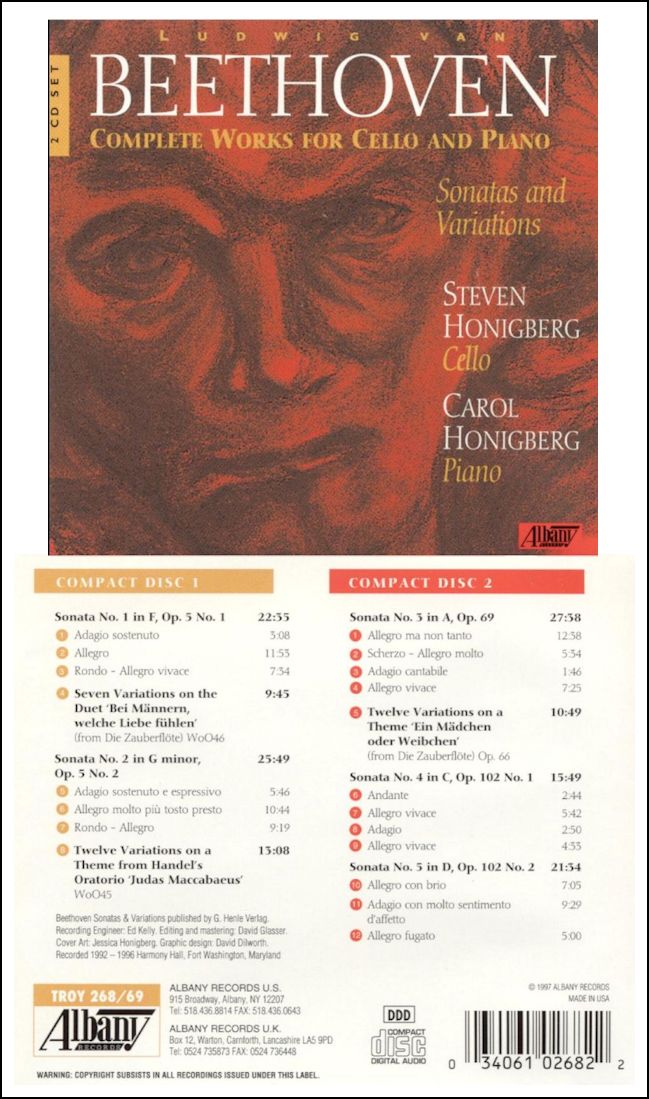

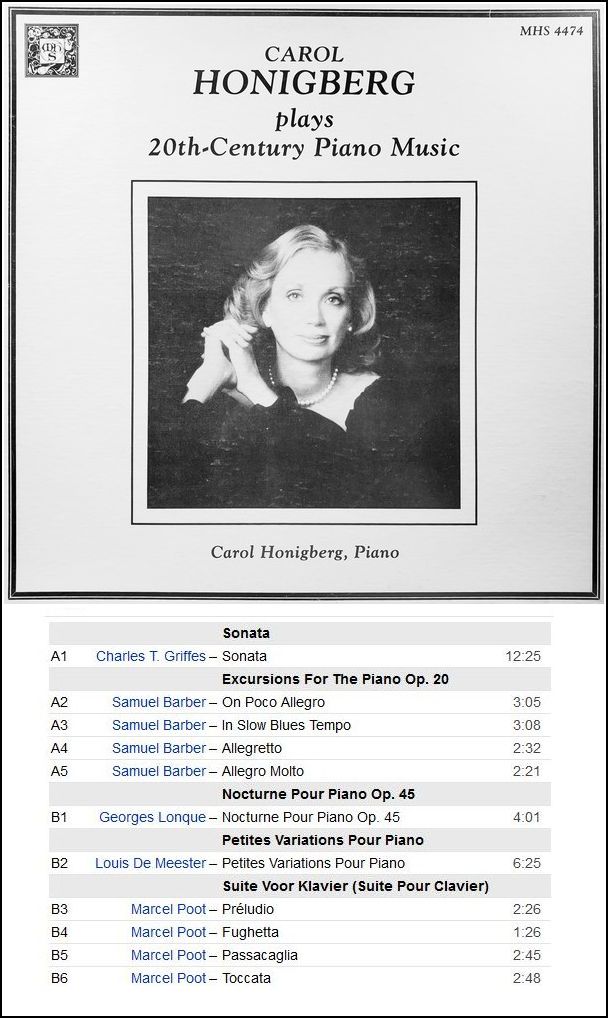

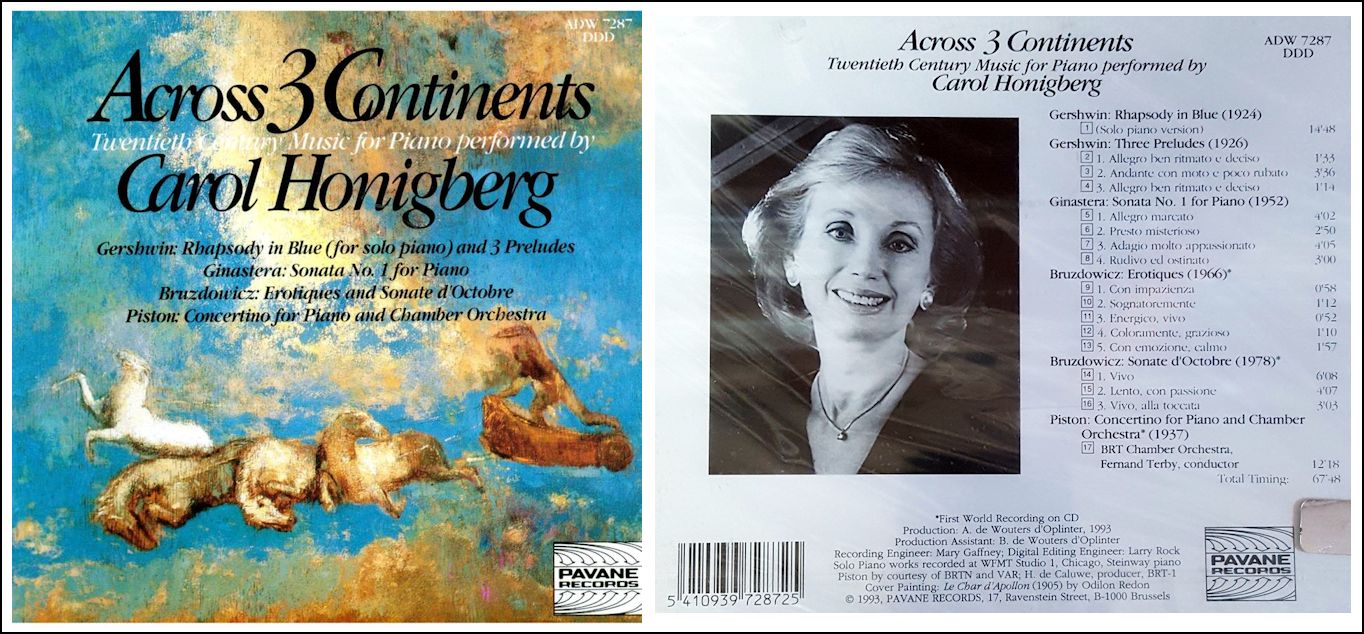

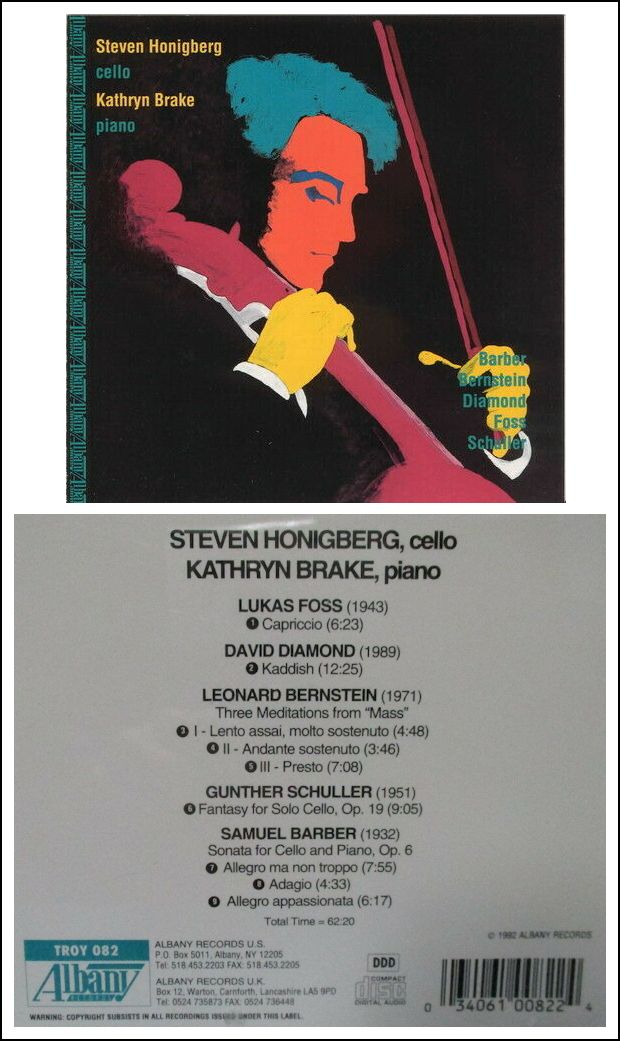

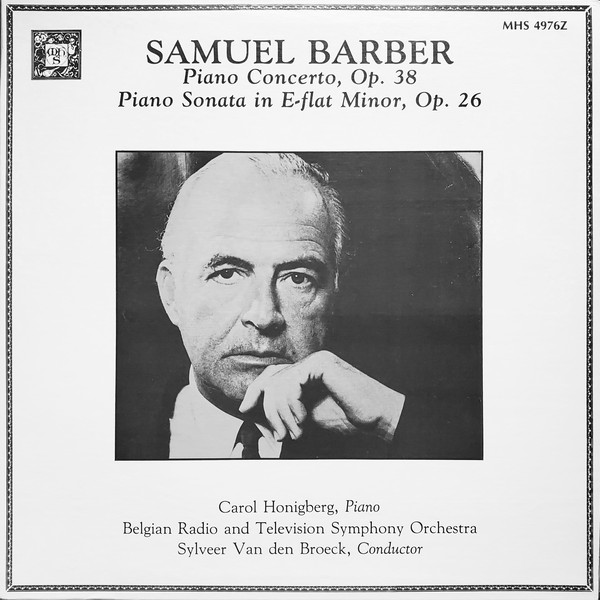

Carol Honigberg received her master's degree in Piano Performance, at Northwestern University and her bachelor's at Roosevelt University. A few of her significant teachers and mentors include former teachers Rudolph Ganz, Cecile Genhardt, and Marguerite Long in Paris, France. She was formerly a Professor of Piano at Roosevelt University, and is currently the Artistic Director of the Pilgrim Chamber Players. Ms. Honigberg has had the honor of performing numerous solo and chamber concerts throughout Europe and the United States, including Alice Tully Hall. Some of her solo appearances were with the Lake Forest Symphony, Grant Park Symphony, Highland Park Strings, and Chicago Chamber Orchestra. In addition to her performances in various concert halls and theater venues, she has also had the privilege to play live recitals on the Dame Myra Hess Recital Series at the Chicago Cultural Center. She also has several recordings which include a 20th Century piano recital on the Pavane label, Beethoven Cello Sonatas and Variations, and Complete Works by Chopin for Cello and Piano with Steven Honigberg on the Albany label. * * *

* *

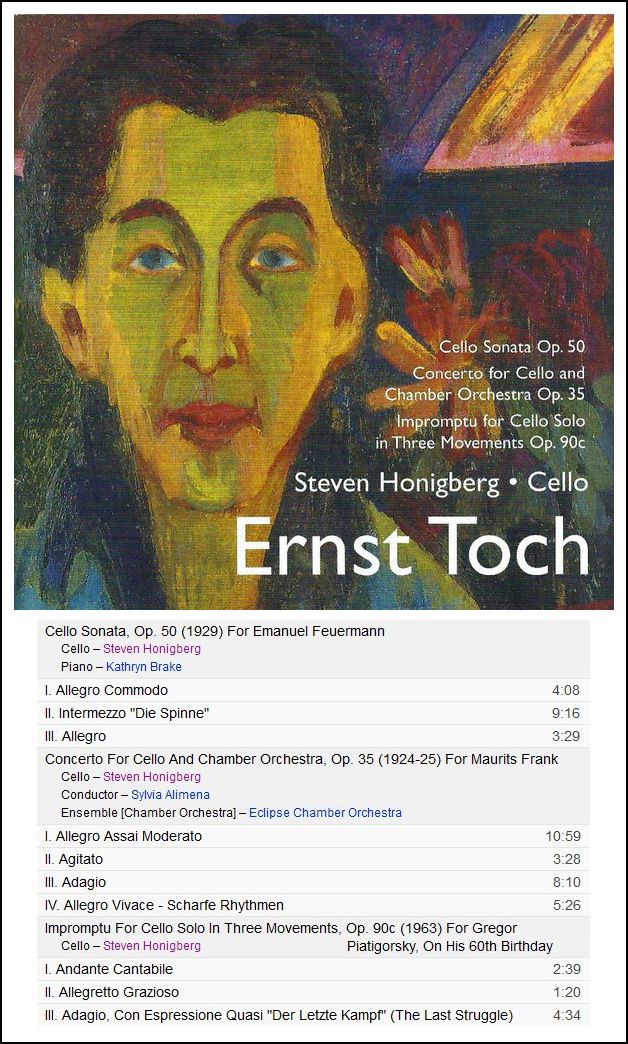

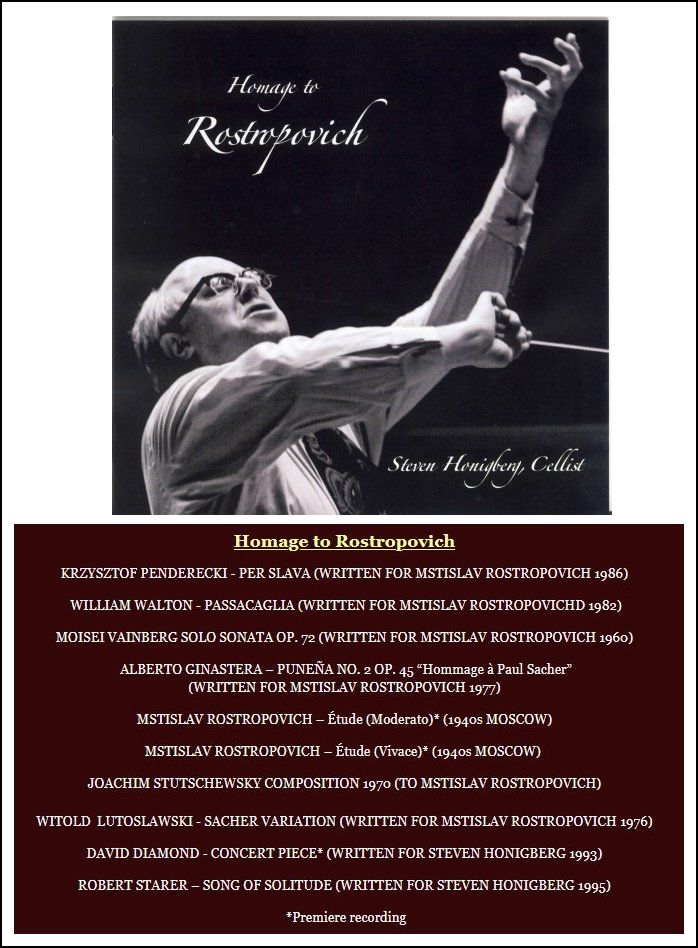

Steven Honigberg, hired by former Music Director Mstislav Rostropovich, joined the National Symphony Orchestra in 1984. That same year he presented his New York debut recital in Carnegie Recital Hall and performed Strauss's Don Quixote with the Juilliard Orchestra in Alice Tully Hall. In 1988, rave reviews accompanied the world premiere of David Ott's Concerto for Two Cellos performed with the National Symphony, Rostropovich conducting. The NSO programmed the work on two subsequent United States tours. Mr. Honigberg is a graduate of the Juilliard School of Music where he studied with Leonard Rose and Channing Robbins. Other mentors include Pierre Fournier and Maurice Gendron. In Chicago (his home town) he has appeared at the Ravinia Festival, and as soloist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Ars Viva Orchestra, Lake Forest Symphony, and New Philharmonic Orchestra among others. He appeared most recently as soloist with the National Symphony Orchestra in 2008 in a performance at the Kennedy Center of Erich Wolfgang Korngold's Cello Concerto. From 1990 to 2009, Honigberg was principal cellist and chamber music director of the Edgar M. Bronfman series in Sun Valley, Idaho, where he was featured as soloist with the summer symphony in concerti by Barber, Bartok, Bloch, Boccherini, Dvořák, Elgar, Goldschmidt, Haydn, Korngold, Popper, Saint-Saëns, Schumann, Shostakovich, Tchaikovsky, and Walton. In the summer of 2014, Mr. Honigberg was professor of cello in an International Course of study in Valbonne Sophia Antipolis, France. Honigberg is a member of Gerard Schwarz's All-Star Orchestra, which in August 2012 convened in New York City to record 8 one-hour programs for PBS television. He is also a member of the Smithsonian Chamber Society, the Phillips Camerata, and VERGE ensemble. As an author, in 2010 his first book was Leonard Rose: America's Golden Age and Its First Cellist. Honigberg performs on a Lorenzo Storioni cello made in Cremona in 1789. |

Steven: They’re different experiences, and there are

pleasures in both. Performing gives you immediate gratification.

You’re striving for perfection, but in a recording you have a chance

to do it over a few times. Then you’re sure to get it. You

could make a mistake, stop, and start again, so as long as your time

is lasting in the studio, you can keep doing it.

Steven: They’re different experiences, and there are

pleasures in both. Performing gives you immediate gratification.

You’re striving for perfection, but in a recording you have a chance

to do it over a few times. Then you’re sure to get it. You

could make a mistake, stop, and start again, so as long as your time

is lasting in the studio, you can keep doing it. BD: Now you’re recording the Beethoven material. Is

this even better than the sound Beethoven would have imagined?

BD: Now you’re recording the Beethoven material. Is

this even better than the sound Beethoven would have imagined?

Steven: Vilnius [Capital of Lithuania].

Steven: Vilnius [Capital of Lithuania].

Ellen Zwilich conceived her Symphony No. 2 to "exploit the

artistry and virtuosity" of the cello section of a modern symphony orchestra.

In the score program note, the composer wrote, "To me, the cello is the

quintessential singer among string instruments, encompassing, as it

does, the entire human vocal range from the lowest bass voice to the

highest soprano. Another aspect of the cello that fascinates me is the

enormous range of expression, so I wanted to explore a wide gamut of techniques

and dramatic moods. Additionally, I find the sound of multiple cellos

thrilling. For these reasons, I decided that I would combine concepts of

symphonic development with a concerto attitude." She continued, "The

work bears the subtitle Cello Symphony because it is a symphony in which

the cello section is the protagonist. In fact, the piece is virtually a

concerto for the cello section, calling for highly virtuosic playing and

exploring the full range and scope of the instrument. The first movement

even has a cadenza for the cello section!"

Ellen Zwilich conceived her Symphony No. 2 to "exploit the

artistry and virtuosity" of the cello section of a modern symphony orchestra.

In the score program note, the composer wrote, "To me, the cello is the

quintessential singer among string instruments, encompassing, as it

does, the entire human vocal range from the lowest bass voice to the

highest soprano. Another aspect of the cello that fascinates me is the

enormous range of expression, so I wanted to explore a wide gamut of techniques

and dramatic moods. Additionally, I find the sound of multiple cellos

thrilling. For these reasons, I decided that I would combine concepts of

symphonic development with a concerto attitude." She continued, "The

work bears the subtitle Cello Symphony because it is a symphony in which

the cello section is the protagonist. In fact, the piece is virtually a

concerto for the cello section, calling for highly virtuosic playing and

exploring the full range and scope of the instrument. The first movement

even has a cadenza for the cello section!"The work was composed in 1985 on a commission from the San Francisco Symphony. It was first performed on November 13, 1985, by the San Francisco Symphony under the direction of Edo de Waart, to whom the piece is dedicated. The symphony has a performance duration of roughly 24 minutes and is cast in three movements in the traditional fast-slow-fast concerto form. |

BD: When you’re asked to play one of these pieces

that was written with him or for him, do you have to be a little bit

like Rostropovich, or are you still completely Honigberg?

BD: When you’re asked to play one of these pieces

that was written with him or for him, do you have to be a little bit

like Rostropovich, or are you still completely Honigberg? Carol: It’s a very special arrangement.

First of all, we speak the same language. Often, you really

can’t really speak with your children in the same language, can you?

As they grow up, they’re doing something else, and they’re on to another

life almost. The communication is different. In this

way, we really are speaking the same language, which is music, and

we can really pull it apart as far as we want to discover every aspect

of the music. This is not just the performances, but the emotions

that go with it — the ups and

downs that music has that you can’t help that come with it. There

are disappointments, and the wonderful thrills. There’s a lot

surrounding a musician, and a career. It goes up and down, even

though an outside person doesn’t see it. It’s a very difficult profession,

actually.

Carol: It’s a very special arrangement.

First of all, we speak the same language. Often, you really

can’t really speak with your children in the same language, can you?

As they grow up, they’re doing something else, and they’re on to another

life almost. The communication is different. In this

way, we really are speaking the same language, which is music, and

we can really pull it apart as far as we want to discover every aspect

of the music. This is not just the performances, but the emotions

that go with it — the ups and

downs that music has that you can’t help that come with it. There

are disappointments, and the wonderful thrills. There’s a lot

surrounding a musician, and a career. It goes up and down, even

though an outside person doesn’t see it. It’s a very difficult profession,

actually. BD: [To Carol] Your career divides a little differently

because you’re also doing some teaching.

BD: [To Carol] Your career divides a little differently

because you’re also doing some teaching.

© 1993 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 15, 1993. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1997, and on WNUR in 2005, 2009, and 2017. This transcription was made in 2021, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.