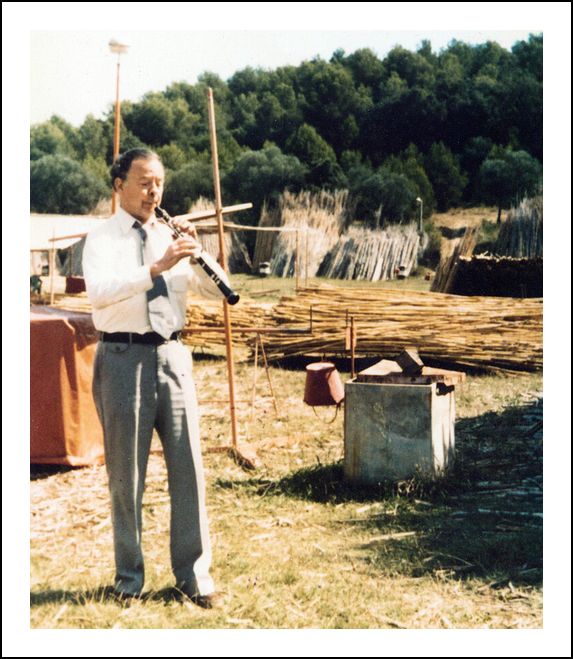

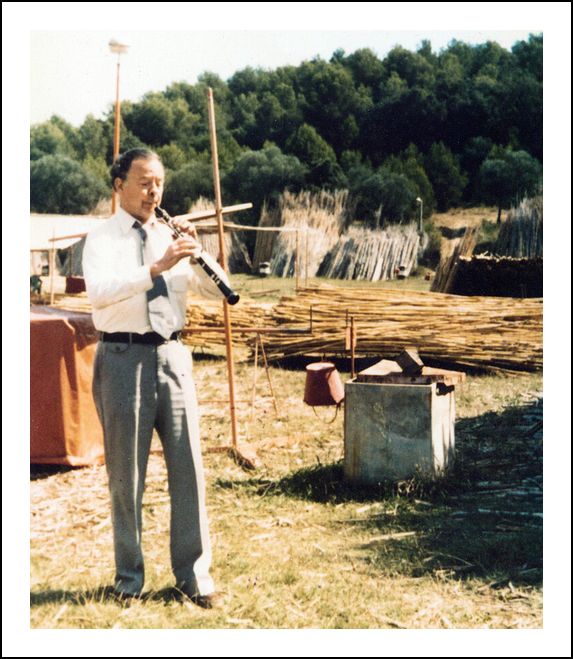

Oboist Ray Still

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

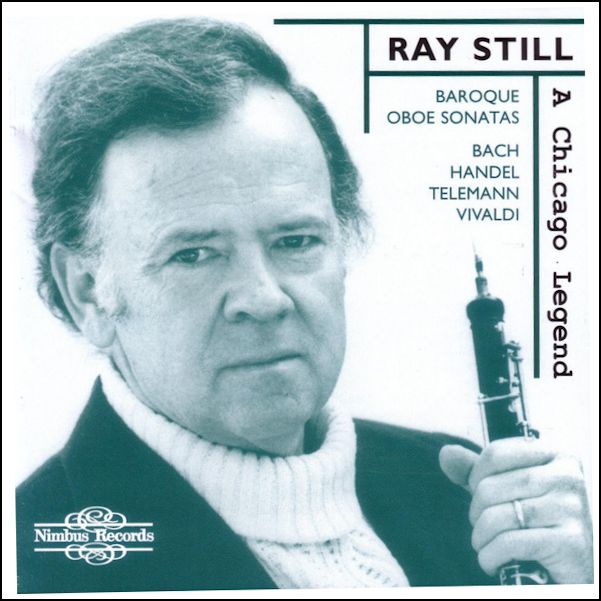

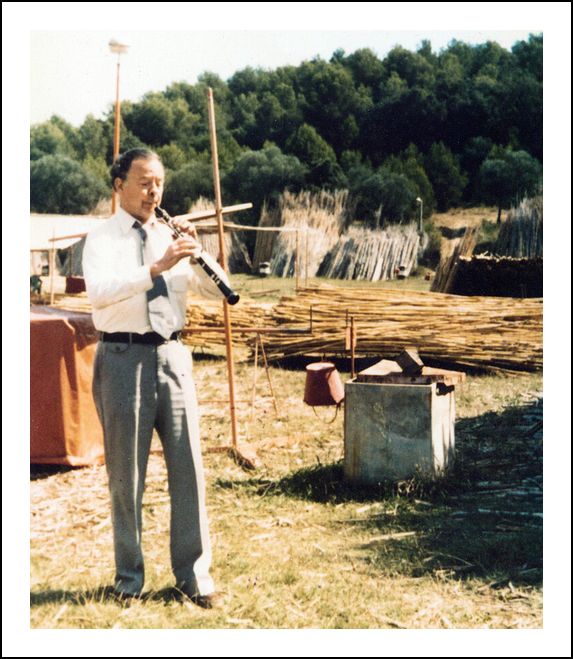

Ray Still (March 12, 1920 - March 12, 2014), was the first oboist

of the Chicago Symphony for forty years. He enjoyed a long and

distinguished career in orchestral, solo, and chamber music. He played

under almost all the major conductors of the last half of the 20th century,

and recorded much of the repertoire for oboe solo and ensemble. The

many students he taught in graduate and undergraduate programs and international

clinics and master classes now staff symphonies and universities around

the world.

After his retirement, he toured in Europe, Ireland, Canada, and Japan

and taught at Northwestern University, and the University of Maryland.

His distinctive tone and musical style have influenced and inspired

musicians throughout the world. Naturally, being brought up in

Evanston (home of Northwestern University), I had become used to the fact

that the Chicago Symphony was at the top of the orchestral world, and

that included the sound Still produced in performance and on records.

While I was with WNIB Classical 97 as Announcer/Producer, I hosted

a long series of programs which included interviews with the composer

and/or the featured performers. Having studied bassoon and contrabassoon

with Wilbur Simpson,

who played Second Bassoon in the CSO for forty-five years, he, as well as

several other CSO musicians graciously allowed me to chat with them for

these broadcasts. Names which are links on this page refer to transcripts

of my interviews which are posted on this website.

In May of 1994, Still had recently retired from the Symphony, and he

invited me to his home to do the interview . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Thank you very much for inviting

me to this lovely environment!

Ray Still: Thank you for coming. You

should see our garden. It’s really gorgeous out in the back yard.

We will go out and see it later. It’s my wife’s pride and joy.

She loves gardening.

BD: Does she like oboe playing?

BD: Does she like oboe playing?

Still: Yes, she likes oboe playing, but

she gets a little sick of it sometimes. I’m on a big practicing

kick right now — long hours

every day getting ready to make some new recordings. So, it gets

a little monotonous. She was asking me if I wanted to go to our

daughter’s place in Springfield, Ohio, for the weekend for Mother’s

Day, and I said, “No, I’m on a roll right now.” Then she came into

the studio and saw me with the Knicks & Nets [basketball] game on.

Luckily, I was also putting my hi-fi together, because the Nets &

Knicks in the next room were in the background.

BD: [With mock disgust] Are you not

a Bulls fan???

Still: [Laughs] I’m a Nets fan right

now because I want them to beat the Knicks. I want all the top

contenders to be knocked off so that the Bulls have a chance! [Much

laughter]

BD: Without Jordan it’s a little harder

for them. [This was when Michael Jordan was playing baseball,

between stints with the Bulls.]

Still: Yes, they’re having a tough time

of it.

BD: They just beat somebody three in a row...

Still: Yes, but it was the Cleveland Cavaliers

without three of their best players.

BD: Well, it’s Chicago without their best

player, so it evens out a little bit.

Still: Yes. They’ve still got Pippen,

and Grant, and Armstrong, so they’ve got three damn good players.

It’s just that they don’t have their Superman! [More laughter]

Did you notice in the paper that they’re putting a Jordan-Watch

on every day? They say what he did each day in baseball.

Every day they show just his eyes, and note that he struck out twice.

BD: Yesterday he got a hit, and a bloop

single.

Still: Yes, something like that. It’s

so silly! Here’s a guy down in a Double-A minor league

— which is third-class

— and they’re riding around in a first-class

bus that he bought them for $350,000! Those guys don’t want him

to be promoted.

BD: [Re-assuringly] Oh, they’ll get

to keep the bus.

Still: Yes, maybe. [Laughter continues]

BD: That was a classy thing to do, rather

than have the team be in an ordinary bus, while he was riding in his

Porsche.

Still: Oh, sure, sure!

BD: There seems to be a connection between

music and sports. A lot of the composers follow baseball, and

a lot of other musicians follow baseball and basketball. Is there

a special connection with all this?

Still: I don’t know that there is.

The guys in the Symphony used to talk sports, but that was probably

the same percentage of sports fanatics that there are as there in the

average population. A lot of the guys would not be interested at

all.

BD: It would be the same as if you went

into any ordinary business office?

Still: Yes, probably. Some of us were

fanatics. The year the Cubs were winning there was a piece in

the paper about my having a radio on stage at Ravinia. It was funny,

because the conductor was Kurt Masur. He

was from an East German orchestra, and at that time it was Communist, where

they could have all the time they want. They didn’t dare protest

about overtime, or playing long hours, so he had all the time he wanted

in the world. But at Ravinia you have to be very thrifty with your

time. He was doing the Beethoven Ninth, and the Choral

Fantasy, and he just was wasting a lot of time, and all the guys were

asking me, “What the hell are the Cubs doing?” This was the

game that could make or lose the season, so I had this radio in my briefcase,

and a little earphone in my ear. I wasn’t supposed to be playing.

I was just supposed to be sitting there watching him explain bowings to the

fiddles, and the guys on either side of me were saying, “What’s the score?”

and I’d say, “Still the same thing!” I didn’t notice Masur him coming

up to me. Suddenly, he was standing right over my music stand, and

he said, “Is that a radio you’re listening to?” I said, “Oh, no, Maestro!

I was just checking the pitch!” [Gales of laughter]

BD: A constant 440 in your ear!

Still: Yes! Anyway, that made the

newspaper. In some ways, we’re pretty fanatical sports fans.

I’ve never done this, but some guys sitting in the back in brass or

percussion, have come with little portable TVs to use when they’re not

playing for a movement. [Continuous laughter throughout all of

this story]

BD: There are occasionally pictures of guys

who play in pit orchestras that have a crossword puzzle on their stand.

Still: Oh, they do. Dale Clevenger, the

horn player, was constantly doing crossword puzzles on the stage.

He had his nose in it all the time...

BD: ...but he never missed an entrance!

Still: Ah... I wouldn’t say that!

If his assistant nudges him in time, he doesn’t miss an entrance!

BD: There are sports fanatics everywhere.

Is it good that there are Symphony fanatics?

Still: Oh, yes! We appreciate

the fact that there are Symphony fanatics and Symphony groupies, and

people that follow the Symphony very closely. Those are our public,

and we know that it’s a much smaller public than the sports audience.

BD: Would you want your audience to be as

big as the sports public?

Still: I don’t know. I don’t

think the audience for great art — the

kind of art in great museums, or the great poetry, or Shakespearian

plays, or serious drama of any kind, or chamber music, or symphonic music

— is ever going to be as large as the

popular things. It’s never going to be as great as an audience for

the rock groups, and the popular groups, and so forth, but that’s the way

it is. The majority probably are people who will never dig below

the surface in any field. They never really put out the effort to

become fanatics.

Still: I don’t know. I don’t

think the audience for great art — the

kind of art in great museums, or the great poetry, or Shakespearian

plays, or serious drama of any kind, or chamber music, or symphonic music

— is ever going to be as large as the

popular things. It’s never going to be as great as an audience for

the rock groups, and the popular groups, and so forth, but that’s the way

it is. The majority probably are people who will never dig below

the surface in any field. They never really put out the effort to

become fanatics.

BD: Is this one of the things that we should

let people know — that classical

music can be enjoyed superficially as well as in great depth?

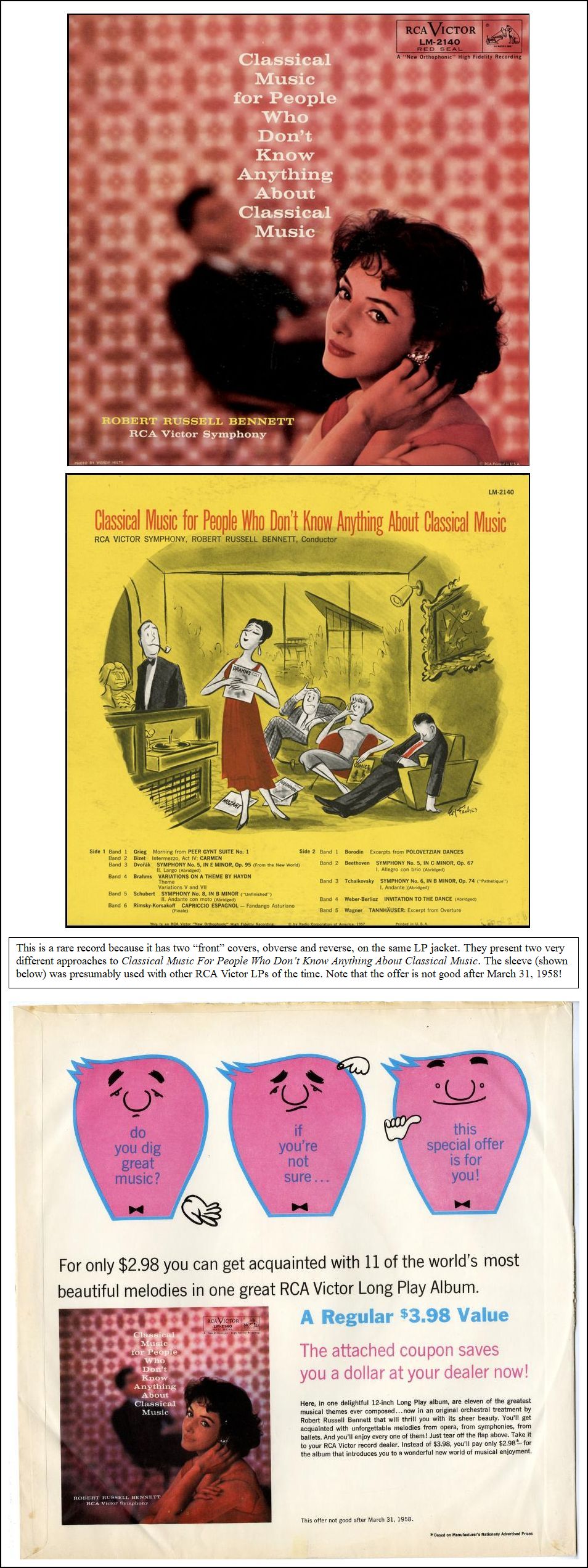

Still: Sure. I once made an album with

Robert Russell Bennett called Classical Music For People Who Don’t

Know Anything About Classical Music! It was just a bunch of

favorite easy, catchy tunes that anybody could like immediately.

There was a little bit from ‘Morning’ of the Peer Gynt Suite, and

the opening theme from Brahms’s Haydn Variations...

BD: Just the big hits?

Still: Yes, the hits. Anybody could

listen to those and say, “I don’t think classical music is so bad.

I can hear some tunes, and even that’s not bad.” [This LP,

with its very interesting visual design, is shown at the bottom of this

webpage.] You can draw people in with Beethoven’s Greatest

Hits, or Bach’s Greatest Hits. Real music-lovers look

down on that sort of thing, but if they drag anybody in, fine!

Even the picture Amadeus — which

I despise, personally. I didn’t

despise every part of it. I liked that one little speech that Salieri

made, where he talked about Mozart’s Gran Partita, and this simple

little bit he put into third movement with the horns, and then this little

syncopated beat comes in. Salieri says that’s all very ordinary,

but then, in the fourth bar, suddenly comes this oboe from heaven!

[Both laugh] I didn’t mind that part! It is a heavenly oboe

part. It’s a part that once you play it, you never forget it, and

once you hear it played really well, you never forget the theme. Salieri

was just dumbfounded by the genius of introducing the theme in that way,

so that’s the part I didn’t mind. However, I just hated the distortion

at the end. It is not facts, it’s fantasy.

BD: But at least now we don’t have to explain

who Amadeus is. Most people now know Mozart, at least a little

bit.

Still: Right.

BD: Is it your responsibility, as an oboe

player, to make sure that any phrase is indeed heavenly?

Still: It depends on your own taste, as an

oboe player, what you think is heavenly. What some oboe players

think is heavenly might include an extremely wobbly heavy vibrato, but

then another oboe player might have a very thin kind of a shaky tone, and

both might say that they are imitating a singer. In fact, all instrumentalists

without exception say, “I’m imitating a singer when I play my instrument.”

BD: Do you encourage this idea when you’re

teaching, to have a singing tone?

Still: Of course, but it all depends.

I encourage my oboe players not to listen to the oboe very much, but

to listen to singers, or violinists, or cellists much more than the

oboe.

BD: Specific singers or just singers?

Still: Very specific singers. I say

not to listen to ordinary singers. Don’t listen to Beverly Sills

in her declining days, where she vibrated a major third on either side

of the pitch. Do listen to anything that Fritz Wunderlich recorded.

Listen to him for a singing tone. Listen to Elly Ameling, who has

one of the truest pitches of any singer that ever lived. She just

has a flawless pitch, and a flawless center to her tone. Also, Fischer-Dieskau,

and Jorma Hynninen, the Finish bass, who has infallible pitch and

a beautiful, beautiful vibrato. I also encourage them to hear Christa

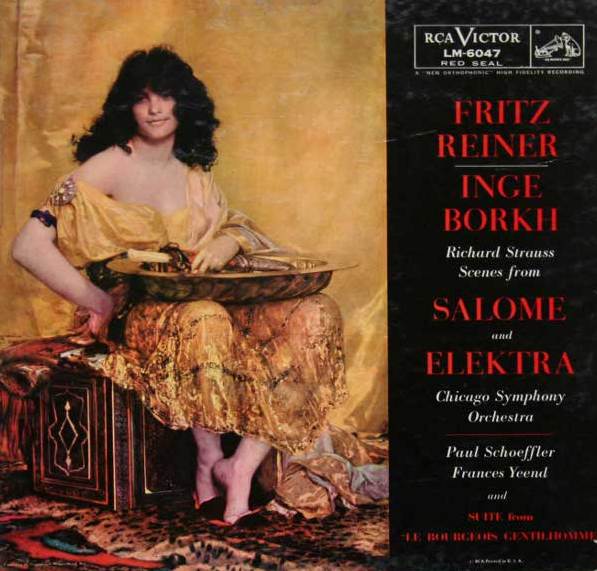

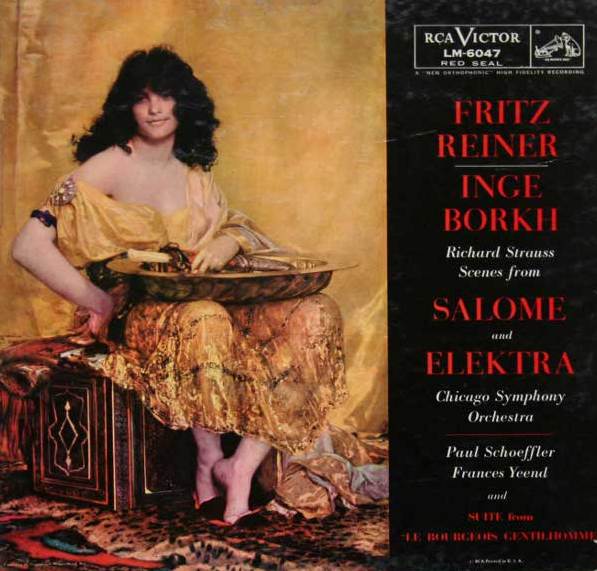

Ludwig in her prime. I often play for them a record that we made

with Reiner of the Soliloquy and the Recognition Scene from Elektra

with Inge Borkh. Nobody could sing any greater than that.

I heard another record of Elektra recently, and it turned out to

be Birgit Nilsson

with the Vienna Philharmonic and Solti conducting. That was pretty

great too, but Inge Borkh just happened to be with us at that time,

and I don’t think we ever made it any more exciting a record than that.

Two scenes from Elektra, and the final scene from Salome.

It was incredible.

To close the Orchestra’s sixty-fifth season, music director Fritz

Reiner chose Strauss’s Elektra. “This was a monumental performance

superbly cast, and scaled to the full grandeur of Inge Borkh’s magnificent

singing in the title role,” wrote Claudia Cassidy in the Chicago

Tribune. “I for one have heard nothing like the outpouring

of that amazing voice since the days of Kirsten Flagstad. . . . This

is a huge soprano, glistening in timbre, most beautiful when it mounts

the high tessitura and welcomes the merciless orchestra of the still fabulous

Strauss. She can ride the whirlwinds, or she can touch, surprisingly,

the heart.”

Borkh committed excerpts from Strauss’s Elektra and

Salome to disc shortly after her performances. With

Reiner and the Orchestra, she recorded Salome on December 10,

1955, and Elektra on April 16, 1956, both in Orchestra Hall.

== From the CSO Archives

Later CD re-issues of this material in "Living Stereo" would also

include Reiner's Dance of the Seven Veils.

On a related note, Solti would conduct Borkh in her U.S.

opera debut as Elektra in San Francisco in September of 1953, and as

Salome at Lyric Opera of Chicago in October of 1956. She was also Sieglinde

in Die Walküre with Solti in both theaters in those same

seasons.

|

|

[Still continues] I’m so fortunate that I was in the orchestra

for those two great eras — Reiner’s

and Solti’s. The rest I could gladly skip, but...

BD: Even when the conducting was perhaps

not as great, you didn’t feel that your playing

would help to raise the standard of the orchestra?

Still: It’s funny, because one of the complaints

that the French conductor, Martinon, made about me was that he felt

that I was sabotaging his concerts. ‘Sabotage’

is a French word. We pointed that out in the hearing that I

had afterwards, where I got my job back. He didn’t understand

that no musician worth his salt could ever do less than his best.

It’s like the short story of the knife thrower. The guy was a knife

thrower, and his wife was the one that he’d outlined with the knives

every night at the circus. He found out that she was cheating

on him, and he was dying to just make a mistake on purpose, and put a

knife right through her heart. But his art was at stake.

She’d stand there laughing at him, because she knew he was the victim

of doing his best all the time. He couldn’t just throw the knives

badly on purpose.

BD: That was her life insurance policy?

Still: Yes. Any good musician can’t

purposely play badly. There’s just too much of a reflection on

your art. You can’t do it in order, as he said, to try to sabotage

the conductor’s concert. You would sabotage your own career.

They don’t hear the notes coming out of the baton, they hear them coming

out of you. So, that was a particularly dismal era for me, but

then Solti came in and made everything right. Solti was a real Mensch,

like Reiner was, too. I was going to leave about the same time that

Solti did, but it was thirty-seven years, and I thought I’d stick around

three more years and make it forty, a nice round number. But I

really probably should have left at thirty-seven years. It was the

end of a magical era, and things didn’t seem the same after Solti left.

BD: [At the time of this interview in May

of 1994, the new Principal Oboe had not yet been selected. Alex Klein would win the

position in 1995.] They’re still working on trying to fill

your position. Is there any correlation between trying to fill

this position in the Symphony, and the Bulls trying to fill the position

now that Michael Jordan has left?

Still: That’s a very flattering comparison.

I would certainly love to be called the Michael Jordan of the oboe.

In fact, somebody sent in a very humorous piece from a suburban

newspaper. It was written as a satirical thing, supposedly about

the year 2001. Michael Jordan had just finished ten years of a successful

baseball career, and gotten three World Series rings, so he’s decided

to become a symphonic oboe player. [Much laughter] The guy

that wrote it was very, very clever, and said he’s having truck-loads of

cane for reeds delivered to his house, in anticipation of going into the

Symphony. After all, he’s only 41, so there’s no reason why he couldn’t

become a great symphonic oboe player. It was a great article.

* * *

* *

BD: Is it satisfying to be Principal Oboe

in the Symphony, and still have a solo career? Also, how did you

balance those two?

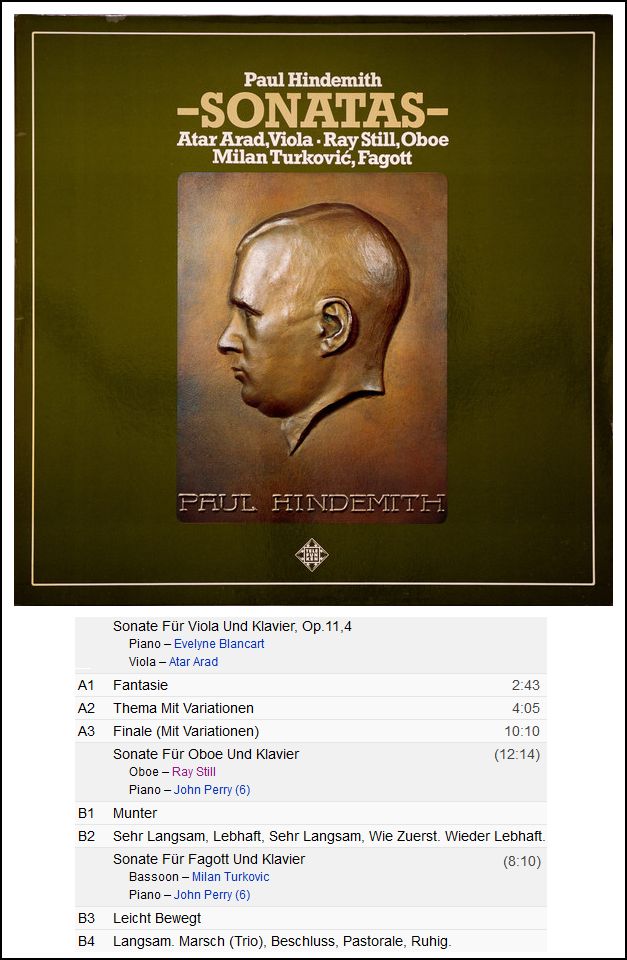

Still: When Solti first came to the Chicago

Symphony, I was really aching to go more into a solo career. That

was, after all, twenty-five years ago. I was fifty years old,

and I’d figured I’d had quite a lot of symphonic oboe playing. I

told him I was thinking of leaving because I wanted to make a lot of

solo recordings, and he was very upset. He said, “My dear, you should

not worry about that because I’m sure we can make some solo recordings

here with you.” A couple of years later I said, “Do you remember

the bit about the solo recordings?” He said, “I didn’t realize

that it’s such an expensive proposition to record with this orchestra.

When you record with the Chicago Symphony, you have to pay the whole

orchestra. So, if you do a Mozart concerto,”

— which I was very interested in doing at that

time — “you have to pay the whole

orchestra!” The whole orchestra means 110 people, even though

you’re only using twenty-five of them. That’s one of the reasons

we don’t record much small stuff. It wasn’t until I was about 65

years old that Claudio

Abbado decided to record four concertos with first chair men

— Adolph Herseth, Willard Elliot, Dale

Clavenger, and myself, on Deutsche Grammaphon. That was the first

and only solo recording I ever made with the Chicago Symphony.

Of course, and made a lot of orchestral recordings with big incidental solos,

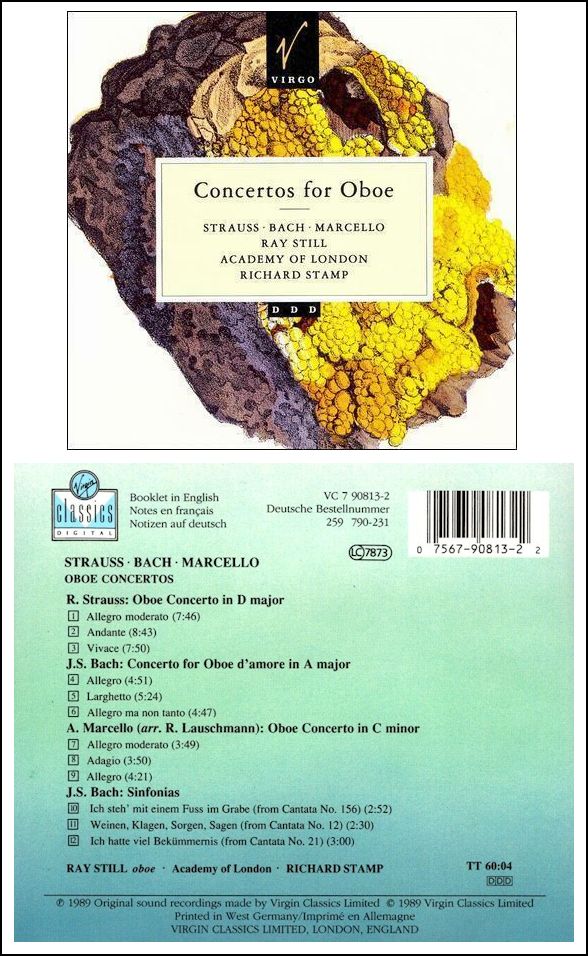

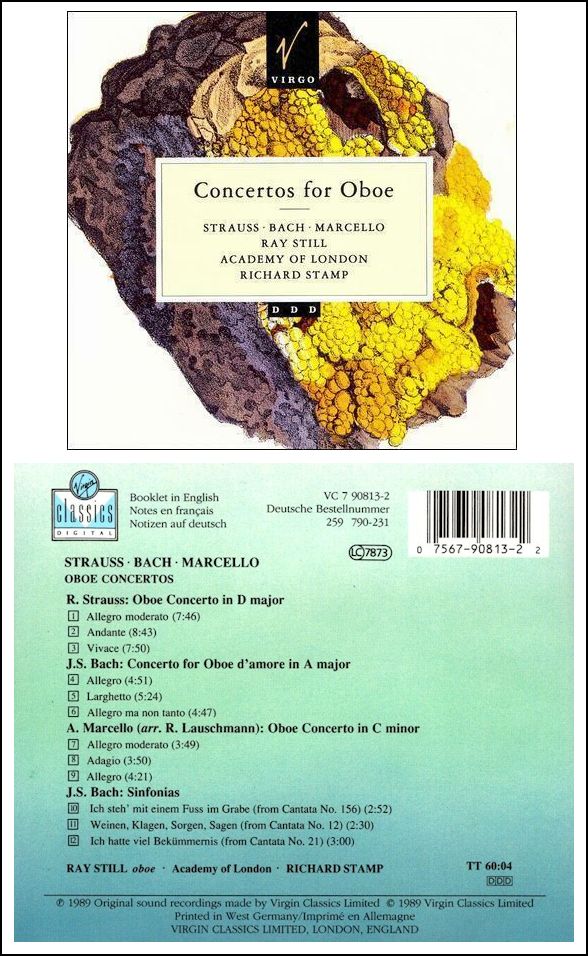

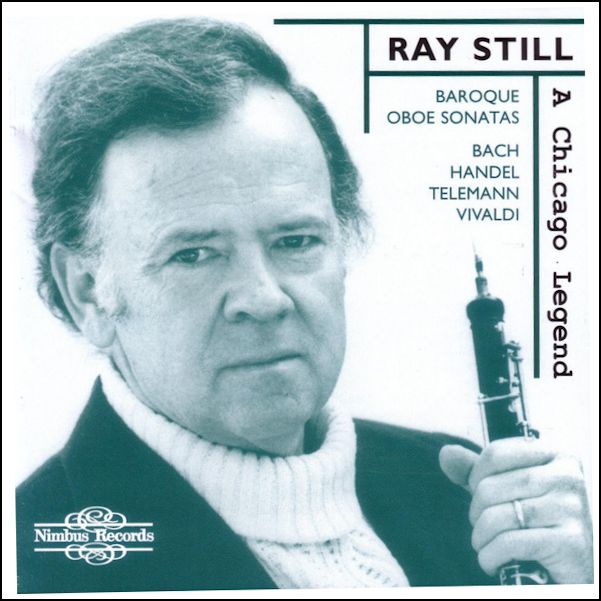

but my name was never on them as a solo player. The next year

after that, I made a solo recording in London, in which I did the Strauss

Concerto, and the J.S. Bach Oboe d’Amore concerto. All

this was after I was 65 years old. In fact, I think I’m the only

oboe player that ever played the Strauss concerto live in person after

70! [Laughs] I did that with Klaus Tennstedt four years

ago. Actually, in a way, I’m glad that I didn’t do my solo recordings

earlier. I did some chamber music recordings, like the one with Itzhak

Perlman, and another with Pinchas Zukerman and Lynn Harrell, plus the

oboe quartet records.

BD: Wasn’t there one

with the Fine Arts Quartet?

Still: Yes, that was about thirty-eight

years ago, when I first came here. Then I did the Bach Double

with Itzhak in Israel, and a few other things, but generally I haven’t

made a great number of solo recordings. But I recorded the things

that I really wanted to record the most, the best pieces of music. The

two best oboe concertos by far are the Strauss, and the Mozart. The

others are way behind those, so I’m glad that I waited until I was mature.

By that time, I had done those pieces many times with the Chicago

Symphony. In fact, I did the Strauss Concerto every ten years

with the Symphony — with Reiner,

with Martinon, with Solti, and finally with Tennstedt, all ten years

apart over a forty-year-period. So, by the time I finally recorded

it, I really knew what I wanted to do with it, because I had heard all

the radio tapes. We had discussed it so many times, and hated

the results, so when I finally got a chance to record it, I knew what

I wanted to do. Incidentally, the reason we were able to do the Mozart

with Abbado was because we put it on the tail end of another recording

session by Schlomo Mintz. His Prokofiev gave us a half-hour to record

the Mozart, after four hours of recording with him.

BD: An Anhang [appendix]!

Still: Yes, right! [Much laughter]

BD: Are you pleased with these solo recordings

now that do exist?

Still: Oh, yeah! I’m very pleased with

the Mozart. It is probably the best thing I’ve ever done, and

one of the best things about it was that it was basically made in thirty-five

minutes. From the take that we did the first day, we threw it all

out except the first page, because I didn’t like the reed that I had.

It just wasn’t satisfactory, and I didn’t even hear the results

because the recording director was sick, and he just didn’t want to play

anything for me. The following day, Abbado forgot to come upstairs.

I was supposed to have forty-minutes, so we had just thirty-five

minutes. This was just enough time to go through it once, and in

fact we started with the second movement. Then we did the third movement

with no stops. We had five minutes left, and I said, “Quick, let’s

go to the first movement, and take the second page.” We just had

barely enough time to go from that second page to the cadenza

— which I had pre-recorded

— so basically the whole thing is like direct-to-disc!

I’m very, very happy with it. I think it’s one of my best. The

Strauss, on the other hand, took six hours to record.

BD: When you make a record, which is presumably

technically perfect, do you set up an impossible standard for yourself

and for others?

Still: [Thinks a moment] I don’t think

so, because there’ll be plenty of other oboe players. Even though

I’m pleased with it, there’ll be plenty of other oboe players of other

‘schools’ of oboe playing. They will pick holes in it and say,

“Oh, my God! Did you hear the way he played that appoggiatura?”

or “Listen how sharp that high D was!” You can take anybody’s recording,

and pick it apart. But just in general, I like it. It represents

the best of my playing. It’s the kind of thing that I want people

to hear if it is still around and can be heard fifty or a hundred years

from today.

BD: It’s in

plastic. Do you not feel that it will be around in a hundred years

from now???

Still: I don’t know. You can’t tell

how those things are going to hold up.

BD: Well, is there such a thing as a musical

perfection?

Still: There is, but sometimes it’s very boring.

I made a record of the Bach big G Minor Sonata for the Swedish

Radio with my son, Tom, which is almost as near as I would probably ever

come to perfection. But even there, I can always hear those little

imperfections in it. However, I would say this one is not boring.

This is probably the best record that I’ve ever made, but none of my

records that I’ve made are ever perfect. There’s always something

that I’m taking a chance with to make it better musically, and if you

are taking a chance, you’re bound to have some little flaws, and I don’t

mind those flaws.

BD: It’s good to have little flaws and a

big sweep?

Still: Yes. It’s not necessary to

have the flaws, and these days with these splicing techniques that

are used, you can hear absolutely apparently flawless records. But

you and I know that those would not really be so flawless if they were

live performances.

BD: Then at what point does this cut-and-splice

become a fraud?

Still: As Herseth said to me many times, the

whole recording business is a swindle. In a way it’s a swindle

if it’s infinitely spliced, but it’s still an art to be able to play well

enough so that you can splice the takes together, or take the best of the

takes, and make it sound continuous as though it’s perfect.

BD: [Gently protesting] But that’s

an engineering art.

Still: Yes, but it’s partly the artist, too,

because people with a lot of experience in recording know how to build

the continuity in there. They know how to keep the same feeling,

even when they’re interrupted several times. When I was rehearsing

with Itzhak Perlman and Pinchas Zukerman and Lynn Harrell in Itzhak’s

apartment in New York, they were always pulling jokes on each other. Itzhak

said, “Pinkie, come here. I want you to hear something.” So,

he took him into the other room, and he played for him the tape of a new

recording that was about to be issued. It was a Sinding piece that

was made famous by Heifetz, and it was just incredible. It was so

spectacular. It just took your breath away. It was absolutely

flawless. Itzhak said, “How do you like it?” and Zukerman said,

“It’s fantastic. I bet you wish you could play like that!”

[Much laughter] Actually, Itzhak can play with that perfection

on occasion, but even with Heifetz, who was known for perfection, you can

hear lots of places in his records where he’s a little out of tune.

BD: He was supposed to be a machine.

Still: Yes, he was a machine. He was

pretty damn perfect, but even so, he was exciting. I haven’t said

he was boring in his perfection.

* * *

* *

BD: Has the standard of playing

— either violin or oboe

— risen over the last forty years?

Still: Oh, very much so. In the movie Fantasia,

I was the stand-in for Marcel Tabuteau. I was seventeen years old,

and I was the stand-in for him on the set as Fantasia was being

photographed. My silhouette was being photographed, but not my

sound. It was Tabuteau’s recorded sound. He was the famous

oboe player who has taught so many oboe players in the United States.

Now, if you listen to his playing in that movie, and if you listen to any

of his other records that he made at that time, there are many students

around today who can play much better than that. Any number of professional

players can play better than he played, but he was a pioneer in developing

a new way of playing, and developing a new kind of sound on the oboe. It

was a new approach.

BD: This is about technical perfection,

and being able to play the notes. Has the musical ability and

musical concentration also gotten better over forty years?

Still: [Thinks a moment] Yes, but the percentage

is about the same of people who are good, journeyman players that you’d

listen to in an audience, and you’d say, “Well, they are good.

That’s a good flute player, or that’s good bassoon playing,” as opposed

to someone whom you listen to and say, “Oh, my God, this is a great music

lesson. Listen to this guy or girl play! It’s just miraculous.

It’s pure musical inspiration coming out of that instrument.”

Now when you can say that, you can also say it has a musical personality

with it. One can talk about how you shouldn’t individualize the

music too much, but the very process of playing is subjective. You

react to the music in your own particular way, and then you play it the

way you feel it, governed, to a certain extent, by the conductor.

If the conductor doesn’t like it, he can always say, “We want it a little

less Schmaltzy there.” In the very seductive solo in the last

part of Afternoon of a Faun, I started to play it and Reiner stopped

me. He said, “Ray, you don’t play with enough color at this point.

I heard Tabuteau play this solo, and he played it...”

I don’t remember whether he said ‘so sexy’

or ‘so voluptuously’.

I hadn’t heard Tabuteau play it, but I took up the challenge, and played

it with more Schmaltz. I don’t know whether that satisfied

him or not, but you sometimes err on the side of not putting enough personality

into it for certain kinds of music, and then at other times, the conductor

will ask for more. I asked Reiner at that time if I had to go with

a glissando downward, and he said, “No!!!”

BD: This is one of the big complaints that

we hear about pianists these days, that they’re all sounding alike, and

they lack individuality.

Still: Yes, that’s true.

BD: With your students, do you try to encourage

their individuality?

Still: Not individuality just to be different.

I encourage them to listen to an awful lot of music, and then follow

their musical instincts, especially, as I said before, not listening

so much to oboe players, but to listen to other instruments. If

you listen to oboe players, you’re listening to the limitations of an

oboe. But if you listen to a really great singer, or a great pianist,

or a great violinist, or a great cellist, you’re hearing the best musical

results by some of the top artists of the world, not just oboe players.

So, I encourage them to go for it. You’re going to be influenced

by your teacher to a certain extent, but I always say that I’m trying not

to tell them how to play the oboe. I’m trying to free them up physically,

and to improve their efficiency in the way they use their body, so that

they can play any way they want. They can play any style, with any

kind of vibrato, any get the sound that they want. That’s my job

is as an ‘oboe doctor’, or an ‘oboe analyst’

— to analyze what is wrong with the way they’re doing it

physically. So many of them end up with so much tension in their bodies

that they end up doing most of the work against their own glottis.

[Demonstrates a tight, gripped throat] You hear even when they talk.

BD: That’s not just the result of the small

bit of breath that has to go into the oboe?

Still: No. When playing the oboe,

you have to fool yourself into thinking that it takes more than a tuba

takes. You actually psyche yourself into believing that you’re

blowing more air through the oboe than you would have to on a low note

of a tuba. By doing that, you keep the blowing muscles free, and

then when all that breath encounters the reed, it sets up a natural

pressure behind the reed. Then your ear tells you exactly how

much to use, and not 1,000th of an ounce more of pressure, or not 1,000th

of a erg more energy.

BD: Have you consulted with Arnold Jacobs

[Principal Tuba with the Chicago Symphony 1944-88] about this?

Still: Oh yes! Jacobs has been my

principal teacher for years.

BD: For breath support?

Still: Or just general use of the body efficiently.

I’ve always said that I really studied with Jacobs, because I

would pick his brain at every opportunity. We actually made some

tests when we were both playing in a band out in Colorado together. He

did some tests, and he checked the way I was using my breath, and found

out that I was using it wrong. He said he talked to some of my students,

and was disturbed by the fact that I was telling them things that he

thought were exactly the opposite of the way they should be done. I

was kind of shocked by that, but then I started talking to him, and I

realized he was right! So, every time I got into any kind of difficulty

through the years, I’d go to Arnold, and he’d get me straightened out.

BD: It’s a great

tribute to a great colleague.

Still: Oh, yes, he’s very unselfish that

way, but I don’t just pass it on. I’m constantly experimenting

on myself, and on my students with the information to prove that it

works. I use myself as a guinea pig, and I use my students as guinea

pigs. Students who come to me might be fairly advanced in their

technical way of playing the oboe, but their tones are very constricted

and very shallow, because they’re blowing backwards.

They’re blowing by locking the muscles down here below the ribs. These

are the muscles which are for the expelling the air, and they’re the

most efficient at emptying your lungs in the quickest way. So, these

students lock those muscles so that they are immobilized. The fact

is that the oboe takes such an incredibly tiny amount of air, they’re able

to play the oboe just by compressing their chests, You might say

it’s like trying to get the toothpaste out of the tube in one swoop, but

only squeezing it at the top. You have to start from the bottom

to get a continuous flow. Oboe players sometimes take a little time

to develop the maturity of sound, the bigness of sound, like singers do.

Singers reach a certain age of maturity when their sound is at its best,

and oboe players tend to do that, too.

BD: Then does it level off, or is there

a decline, and can you maintain it?

Still: It all depends. Like singers,

there are stories of some tenors who sang beautifully until they were

seventy-five years old, and still had very clear voices. Then you

have people who sang beautifully, and suddenly stop at about forty. Many

singers seem to hit their peaks around forty-five or fifty, and then start

declining. The strange thing is that in Europe, everybody was always

so amazed that I was still playing the oboe in the Chicago Symphony at

the age of seventy-three, or seventy-four. Over there, there’s

a stipulation that they retire from the First Chair when they’re sixty.

BD: Can they stay in the section, but stop

being Principal?

Still: Yes. In some places, they don’t

have that anymore. They can stay but they choose not to.

It’s too hard on brass players especially. They’re astounded that

Bud Herseth can still play all the high trumpet parts, and he’s just six

months younger than I am. He’s also seventy-four. [Herseth

was Principal Trumpet in the CSO from 1948-2001, and continued in the section

until 2004.]

BD: The voice is a muscle that can deteriorate

with age. With the oboe, you have the embouchure that’s a muscle,

but it’s not actually what is producing so much of the sound.

It’s controlling the sound.

Still: It’s

controlling the sound, but the main thing that’s controlling the sound

is the breath, and that’s the main thing that’s controlling the voice

also. I heard Hans Hotter sing an incredible song recital in

Aspen. At a party afterwards, some woman asked him, “How do you

get that incredible control all through your upper range, and through

your lower range?” He said, “It’s the breath. Once you learn

the breath, that’s everything.” Now, that isn’t exactly true, any

more than somebody who would tell you that baseball is all pitching.

That’s an oversimplification. Somebody’s got to catch the ball,

and you have to have several other players out there besides the pitcher

and the catcher who are pretty damn good, because you can’t strike out

every batter. Then it would be a hundred per cent of the game.

But in brass or woodwind playing, the efficiency with which you use the

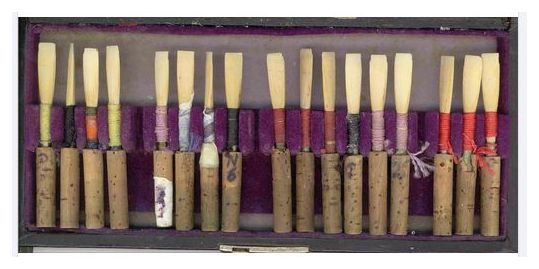

breath is such a huge part of it. Of course, in oboe playing the

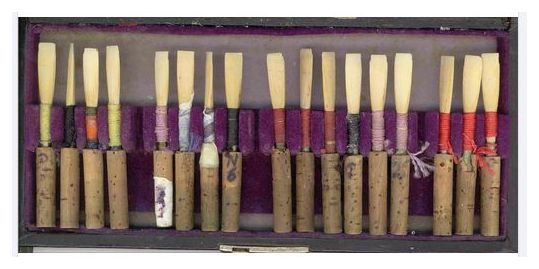

reed is important, too. You have to have a pretty good reed, and

it takes an awful long time to develop the ability to make these reeds.

You’re really making the major part of your instrument every day.

Still: It’s

controlling the sound, but the main thing that’s controlling the sound

is the breath, and that’s the main thing that’s controlling the voice

also. I heard Hans Hotter sing an incredible song recital in

Aspen. At a party afterwards, some woman asked him, “How do you

get that incredible control all through your upper range, and through

your lower range?” He said, “It’s the breath. Once you learn

the breath, that’s everything.” Now, that isn’t exactly true, any

more than somebody who would tell you that baseball is all pitching.

That’s an oversimplification. Somebody’s got to catch the ball,

and you have to have several other players out there besides the pitcher

and the catcher who are pretty damn good, because you can’t strike out

every batter. Then it would be a hundred per cent of the game.

But in brass or woodwind playing, the efficiency with which you use the

breath is such a huge part of it. Of course, in oboe playing the

reed is important, too. You have to have a pretty good reed, and

it takes an awful long time to develop the ability to make these reeds.

You’re really making the major part of your instrument every day.

BD: How long should a reed last?

Still: I had one amazing reed last summer that

I kept ‘babying’, and not playing on it for anything that was unimportant.

I played it for mostly the important solos, and it lasted me something

like five weeks. I was so happy with it. I played the big solos

in the Brahms Violin Concerto, which started the season, and Romeo

and Juliet of Berlioz, and the Shostakovich First. I

just saved it for those, and I didn’t play it in rehearsals at all.

[Laughs]

BD: Generally, though, how long do they last

— maybe a week?

Still: Probably a week. Maybe you

can coax two weeks out them, but you have to rotate them. If

you play six hours a day with really brutal treatment, you’re going

to have a wet dish rag on your hands. They just can’t take that

continuous blowing.

BD: Do you ever envy the flute players that

don’t have to tinker with reeds at all?

Still: Yes... but they envy us because we

have our excuses for playing badly. [Big burst of laughter]

* * *

* *

BD: Let me ask the big philosophical question.

What’s the purpose of music?

Still: Hmmm... You’re talking generally

for the world’s population?

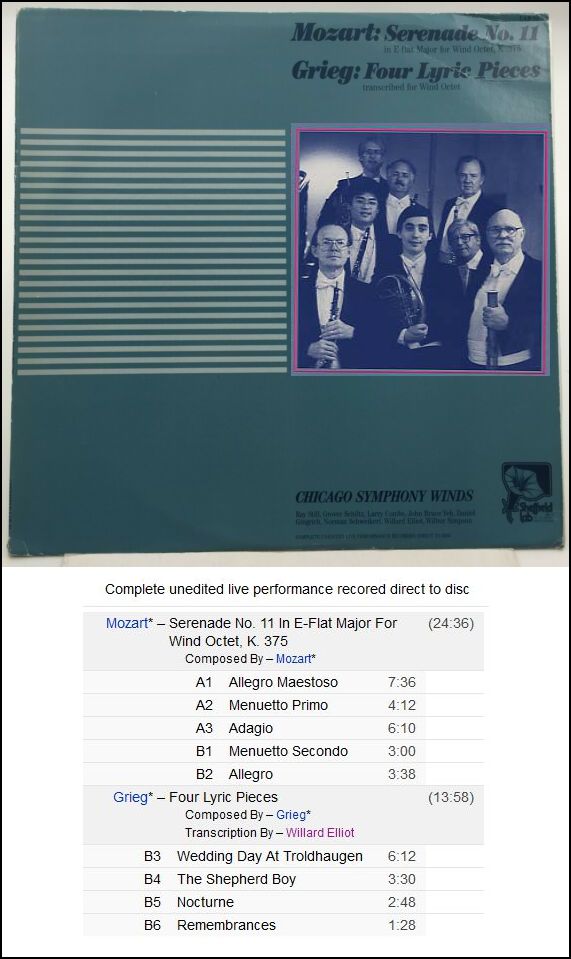

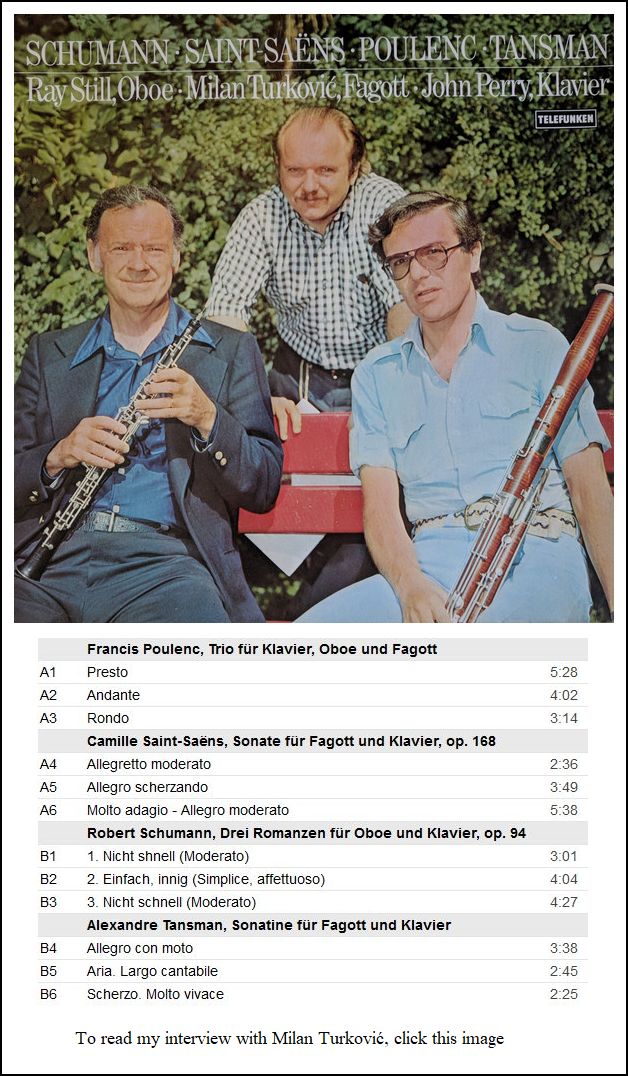

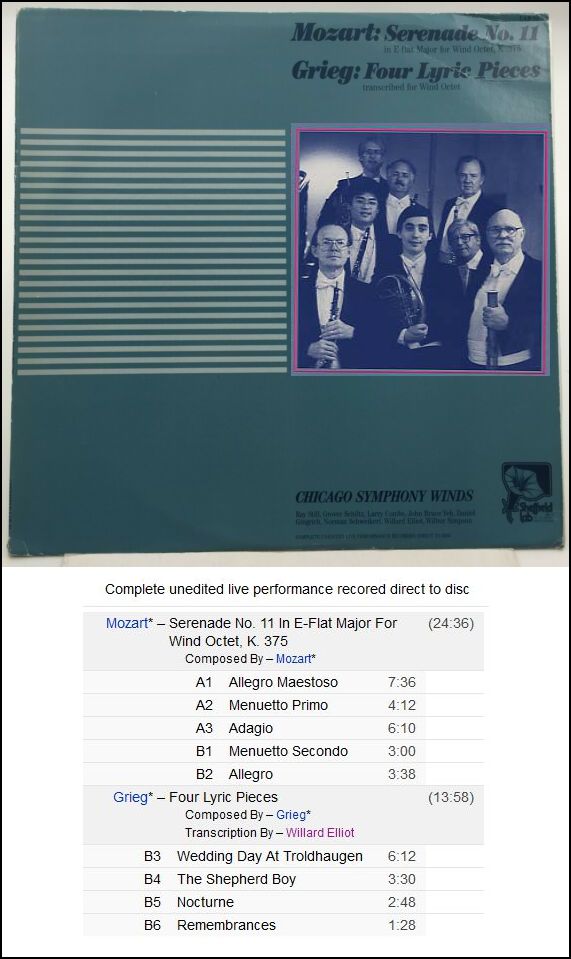

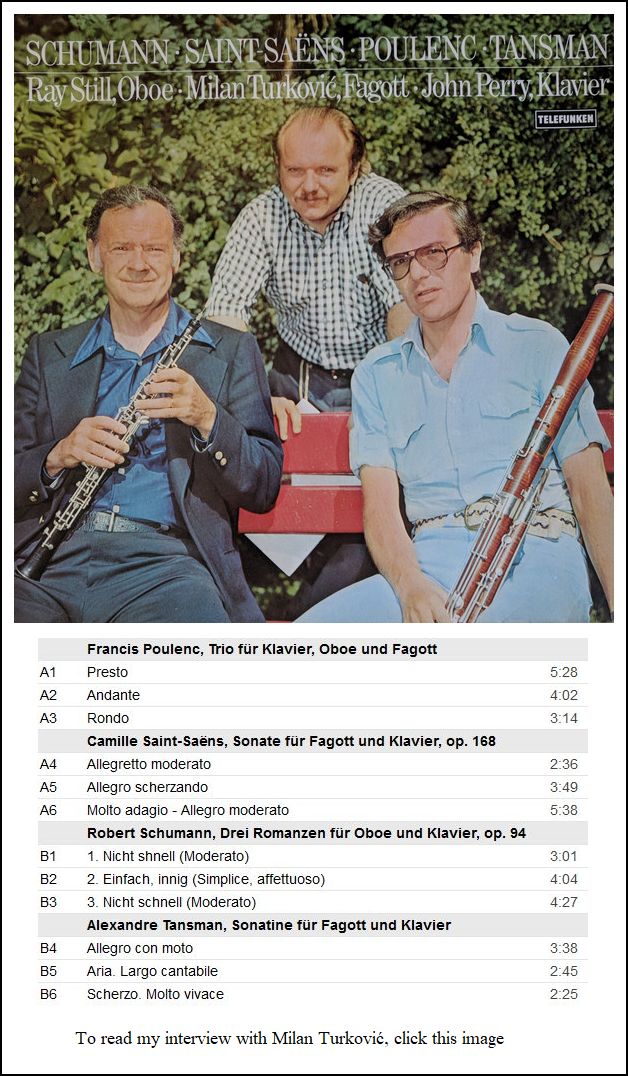

BD: Yes. [Vis-à-vis

the photo on the record cover at right, the performers are Williard Elliot

(also the transcriber of the Grieg) at far right, immediately left of

him is Wilbur Simpson, and behind Wilbur is Ray Still. Others shown

(l-r) are Grover Schiltz, oboe, John Bruce Yeh, clarinet,

Norman Schweikert (top), horn, Larry Combs, clarinet,

and Daniel Gingrich, horn.]

Still: I don’t know. It seems to be

a necessity. People have always had music, even if it’s only been

rhythmic. They’ve had some kind of music since the beginning of

time. The oboe goes back to ancient Egypt, and maybe before that

as some sort of double-reed instrument. There’s some kind of a

need for music. Whether it’s for playing an instrument, or for

singing, there seems to be a basic psychological need for release of emotion

through musical sound. It all depends. There are so many different

kinds of music. I have a grandson who’s mostly interested in rock,

and the stuff that he’s interested in absolutely puzzles me that he can

listen to stuff that is monotonous and simplistic. My second love,

besides symphonic and chamber music and so forth, is jazz. I listen

to jazz quite a lot, to the point that my wife says, “Will you stop playing

that stuff and listen to something else. You’re beating a dead horse

by playing that stuff so much!” I play things mostly from the late

’30s through the early ’50s.

BD: Isn’t that when

it was the most complex?

Still: Not necessarily the most complex.

It got complex in the middle ’40s when Dizzy Gillespie

and Bird (Charlie Parker) were combining to start the Bop era.

It got pretty complicated with the chord structures of Lenny Tristano,

and a lot of the music of that period began to get quite complex harmonically.

I’m not over-enamored of the Bop school, and in its early form it didn’t

really last very well. I’m interested a lot in early recordings of

what I would call chamber music — the

small recordings of Billie Holiday, and Lester Young, with the all-star

groups that were behind them. I have three CDs that include all

the Columbia recordings that I listen to an awful lot, and I listen to

the 1928-1930 records of Louis Armstrong, and Ben Webster, and Coleman

Hawkins. I also listen to a lot of records of the Duke Ellington Band

and the Count Basie Band.

BD: Does all of this make you a better musician,

and in turn a better oboe player?

Still: It certainly has an effect on my playing,

and on my expressiveness on my instrument. For instance, I’ve developed

a philosophy which is, in some ways, influenced by Johnny Hodges, the

great alto player with the Duke Ellington Band for many years, and Lester

Young. Most jazz players are not worthy of their salt if they can’t

make a glissando between notes on the instrument like the human voice.

There have been so-called jazz oboe players, but they’re completely unable

to imitate the jazz glissando. I make it part of the training of

my students that the glissando is a must. They must be able to glissando.

BD: It that, maybe, why Reiner didn’t want

it, because he’d never heard it? Maybe he should have heard you

do it!

Still: [Laughs] No, he had heard me

do it. There’s a place in Rhapsodie Espagnole of Ravel

where there’s a little melody in the cellos [sings it with a glissando

semitone]. It’s a beautiful little glissando. It’s just a

half-tone glissando, and then the oboe has it later, and I would do the

same. Frank would always look over at me and laugh because an oboe

is not supposed to do that.

BD: On a string instrument it’s easy, but

on the oboe it’s very difficult?

Still: It’s just the ability to do it. Herseth

can do it on the trumpet very well, and Peck does it on the flute.

Most people can do it. [Reiner appointed Donald Peck as Assistant

Principal, then promoted him to Principal the following year. He

remained with the Orchestra until 1999.]

BD: Of course, the clarinet player has to do it

to open Rhapsody In Blue.

Still: Yes, they have tricky ways of doing

that. They do partly finger-glissando by half-holing the fingers

and gradually lifting them, but my God, if you’d listened to Barney Bigard

of the old Duke Ellington Band, it was such a supple instrument.

He glissandoed from anything to anything. It was just like a

voice. That’s one of the things which makes playing flexible, and

allows you to play more expressively, and make it more like a human voice.

A human voice doesn’t have any keys that you can press. With

the human voice, you have to make the notes, and it’s almost impossible

to go from one note to another in the voice without some sort of little

transition between them, unless you stop the tone, and make it staccato.

BD: I was always amazed at Birgit Nilsson when

she would sing Brünnhilde’s Ho-Yo-To-Ho

in Die Walküre. It sounded almost like a clarinet

hitting the register key for the octave skips. There was no glissando

there, nothing in between those notes. It wasn’t smeared, and it

wasn’t a slide.

Still: Right, but if you slowed it down

to about one-fourth the speed, you’d hear that she does it so cleverly

that it’s integrated. It’s totally smooth. String players

treat that as part of their expressiveness on their instruments.

I believe in that kind of flexibility.

* * *

* *

BD: I want to ask you now about new music.

Are there some new concertos being written for the oboe?

Still: Yes there are, but I don’t play them.

I leave that to the younger players. There are plenty of players

who don’t feel comfortable with Mozart, and don’t feel quite at home

with Bach and Strauss, so they become specialists at newer music.

BD: Would you advise someone who’s writing a work

for the oboe, to include these glissandos that we’re talking about?

Still: They do now. They have them

written in. I was showing a student how to do these half-tone

glissandos when they were written into the music just recently.

BD: Without mentioning specific names,

are there any concertos or solos being written today that will take

their place alongside the Strauss and the Mozart?

Still: I really wouldn’t know because

I’m not that interested. Don’t get me wrong... I am interested in

contemporary music. I heard a recital just two days ago with Easley Blackwood and

a very good violinist, Sharon Polifrone. She was excellent, and

they played one of Blackwood’s sonatas for violin and piano. They

also played an Ives sonata, a Beethoven sonata, and another piece at

the end. I actually enjoyed Easley’s piece more than the Beethoven

sonata. The Beethoven sonata was good, but maybe it was just the

fact that the Blackwood sonata was more unusual, or maybe it could have

had something to do with their playing in the Beethoven.

BD: Was the Blackwood a new work, or an

old work? He has recently come back to the tonal system.

Still: Yes he has, and he says that

this work is not the kind of work that he really is very much enamored

with these days, but he still doesn’t mind it being played. But today

he’s writing totally different music. The Fifth Symphony

that the Orchestra played is almost like Sibelius. Like

Somerset Maughan said once, “When ten new books come out, I read an

old one!” [Both laugh] I’ve enjoyed playing some of the contemporary

stuff, but I enjoy listening to it in the audience much more than playing

it. Some of the things I used to hate to play, because it made

you feel so stupid as a player. It didn’t require any of the techniques

that you studied so hard all your life to produce a beautiful sound.

It just said, “Play all these notes, and you can play any notes you want,

and just make some general sounds.” They didn’t show whether it was

ugly or pretty.

BD: [Indicating a bright idea] But

if it says to play any notes you want, you can select Telemann’s!

Still: Yes! In one piece maybe by

John Cage, he said, “You

can sit anywhere you want in the orchestra, and you can play any instrument

you want!” The music was in little frames, and didn’t have any

notes. It just told you whether to go up or down. [Laughing]

Imagine a fiddle player there trying to go up and down on a flute...

BD: We’re back to Michael Jordan again,

when he starts playing oboe after being a baseball player!

Still: Yes!

BD: Are you optimistic about the whole future

of music, and of oboe playing?

Still: Oh, sure! The way things are

happening now, there’s so many young virtuosos on the oboe that they’re

going to take it to much greater heights. There are going to

be ten skillful technicians, and ten very good oboe players for every

unusual oboe player — somebody

who has really something to say. They don’t often have that much

to say musically, any more than you’d say that of ten fiddle players that

you hear around today.

BD: Will many of these good technicians fill slots

in orchestras, and do very well for themselves?

Still: Oh yes! But the ones who will really

put the art ahead are those with a super-imagination. They will

carry the expressiveness of the instrument further, and the technique,

too. But there’s so many technicians on the oboe. I served

on the jury in Munich at one time. There were sixty oboe players

there, and every one of them had fabulous fingers. Every one of them

was able to finger the passage, so you have to come to the conclusion that

the fingering part of the oboe is by far the easiest part, because so many

people can do it well.

BD: You get that down, and that’s the

beginning? From there you take off?

Still: Yes, but you keep improving.

You keep practicing your fingering technique. Some people are

obsessed with it, and they go through all these études books.

They think the more complicated études they play, the better

they’re going to get, not realizing what the really difficult thing is

to do on the instrument. If I would write a resumé on these

people, I’d say “Fantastic fingers!” That would be my first comment,

and then I’d say, “Tone very boring, spread, dull. Intonation very

inaccurate.” They would always start out with fantastic fingers,

and after a while, I’d start writing “Fantastic fingers... so what?”

Everybody had fantastic fingers. If the fingers were everything,

you could teach a very dexterous stenographer to play Daphnis and

Chloé on the oboe in about six months.

BD: It’s also got to be musicianship?

Still: As Hans Hotter said, it’s first the

breath, and after that comes nothing for a long time. Then comes

the embouchure. Next after that in importance comes the tongue,

and after that come the fingers.

BD: We haven’t talked at all about baroque and

other early instruments. What are your thoughts on these?

Still: For a long time I didn’t like the

sound they were getting on recordings of baroque instruments, but recently

I’ve heard a lot of players who do very, very well. Some of the

players from a group in Cologne, for instance, do very well, as do The

London Consort with Trevor Pinnock. They had one fellow who was

an American, who died recently, and now there’s Richard Goodwin who plays

very well. They play in tune, and there’s something about the sound

of a baroque instrument for certain kinds of music which is better than

certain kinds of modern instruments, especially where you get the hard

thin tone on the modern instrument.

BD: Have you ever played the older instruments

yourself?

Still: No, I haven’t. We have a player

in the orchestra, Grover Schiltz, the English Horn player, who likes

to play around with them. He also plays the classical oboe, and so

forth.

BD: He had a little solo for oboe d’amore

not too long ago. It was just part of the instrumentation that

called for it.

Still: Yes. When I was playing, usually

the one who played the oboe d’amore was Michael Henoch, who is the Assistant

Principal. He would play the oboe d’amore when it was called for

in a Debussy piece, for instance, or in the Ravel’s Bolero. In

the Domestic Symphony of Strauss he would stick to the English

horn, but now that they have only have a three-men section, I’m not sure

who does which.

BD: Grover played it a couple of weeks ago.

They’ve had to shuffle a little bit, and Grover has even played

Principal a couple of times. They’re trying to uphold the section

while you’re not there. They’re trying to find someone to fill

your shoes, and those will be very difficult shoes to fill!

Still: Thank you very much!

BD: Thank you for being such a fine musician,

and giving your talent to the Chicago Symphony for forty years.

Still: Thank you! I enjoy listening

to your station. I listen to it all the time.

© 1994 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at the home of Ray Still in suburban

Chicago on May 6, 1994. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following

year, and again in

2000. This transcription was made in

2022, and posted on this website at that time.

My thanks to British soprano

Una Barry for

her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this

website, click here.

To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as

well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster

Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975 until

its final moment as a classical station in

February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared

in various magazines and journals since 1980, and

he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to

visit his website for

more information about his work, including

selected transcripts of other interviews, plus

a full list

of his guests. He would also like to call your attention

to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

BD: Does she like oboe playing?

BD: Does she like oboe playing? Still: I don’t know. I don’t

think the audience for great art — the

kind of art in great museums, or the great poetry, or Shakespearian

plays, or serious drama of any kind, or chamber music, or symphonic music

— is ever going to be as large as the

popular things. It’s never going to be as great as an audience for

the rock groups, and the popular groups, and so forth, but that’s the way

it is. The majority probably are people who will never dig below

the surface in any field. They never really put out the effort to

become fanatics.

Still: I don’t know. I don’t

think the audience for great art — the

kind of art in great museums, or the great poetry, or Shakespearian

plays, or serious drama of any kind, or chamber music, or symphonic music

— is ever going to be as large as the

popular things. It’s never going to be as great as an audience for

the rock groups, and the popular groups, and so forth, but that’s the way

it is. The majority probably are people who will never dig below

the surface in any field. They never really put out the effort to

become fanatics.

Still: It’s

controlling the sound, but the main thing that’s controlling the sound

is the breath, and that’s the main thing that’s controlling the voice

also. I heard Hans Hotter sing an incredible song recital in

Aspen. At a party afterwards, some woman asked him, “How do you

get that incredible control all through your upper range, and through

your lower range?” He said, “It’s the breath. Once you learn

the breath, that’s everything.” Now, that isn’t exactly true, any

more than somebody who would tell you that baseball is all pitching.

That’s an oversimplification. Somebody’s got to catch the ball,

and you have to have several other players out there besides the pitcher

and the catcher who are pretty damn good, because you can’t strike out

every batter. Then it would be a hundred per cent of the game.

But in brass or woodwind playing, the efficiency with which you use the

breath is such a huge part of it. Of course, in oboe playing the

reed is important, too. You have to have a pretty good reed, and

it takes an awful long time to develop the ability to make these reeds.

You’re really making the major part of your instrument every day.

Still: It’s

controlling the sound, but the main thing that’s controlling the sound

is the breath, and that’s the main thing that’s controlling the voice

also. I heard Hans Hotter sing an incredible song recital in

Aspen. At a party afterwards, some woman asked him, “How do you

get that incredible control all through your upper range, and through

your lower range?” He said, “It’s the breath. Once you learn

the breath, that’s everything.” Now, that isn’t exactly true, any

more than somebody who would tell you that baseball is all pitching.

That’s an oversimplification. Somebody’s got to catch the ball,

and you have to have several other players out there besides the pitcher

and the catcher who are pretty damn good, because you can’t strike out

every batter. Then it would be a hundred per cent of the game.

But in brass or woodwind playing, the efficiency with which you use the

breath is such a huge part of it. Of course, in oboe playing the

reed is important, too. You have to have a pretty good reed, and

it takes an awful long time to develop the ability to make these reeds.

You’re really making the major part of your instrument every day.