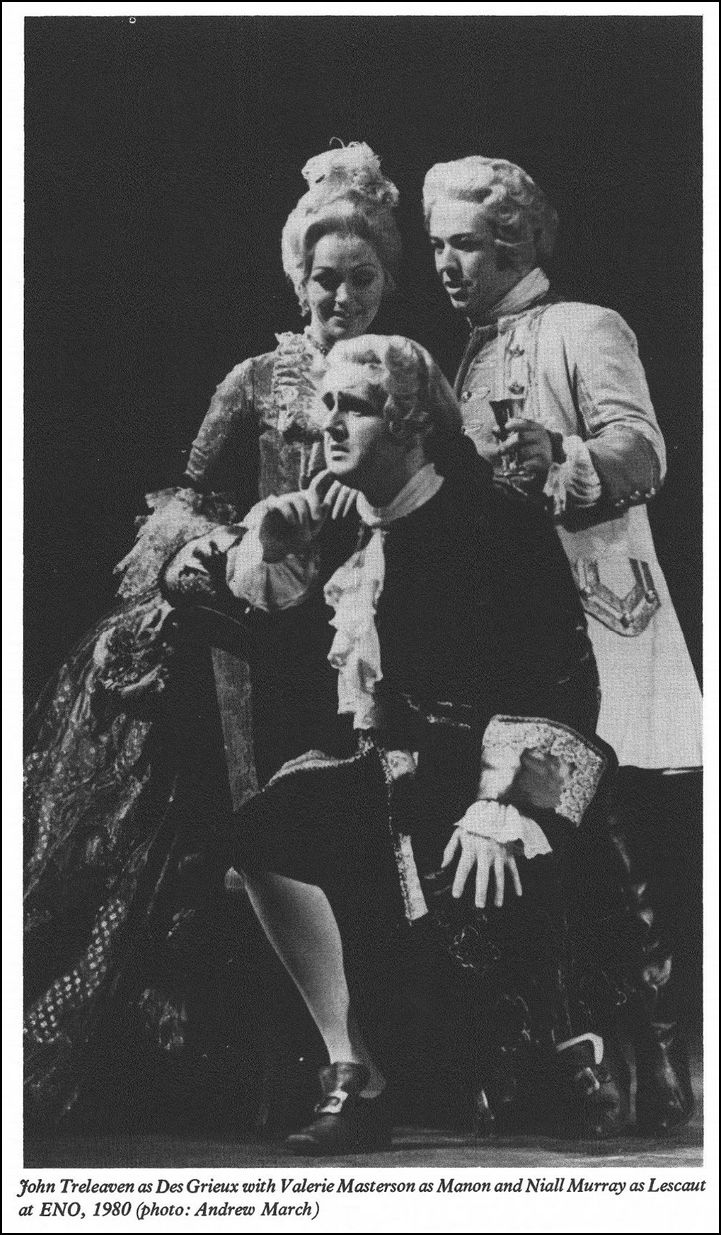

BD: Tell me about the role of Manon.

Do you enjoy her?

BD: Tell me about the role of Manon.

Do you enjoy her? BD: That’s interesting.

I usually think of that role as going to a mezzo.

BD: That’s interesting.

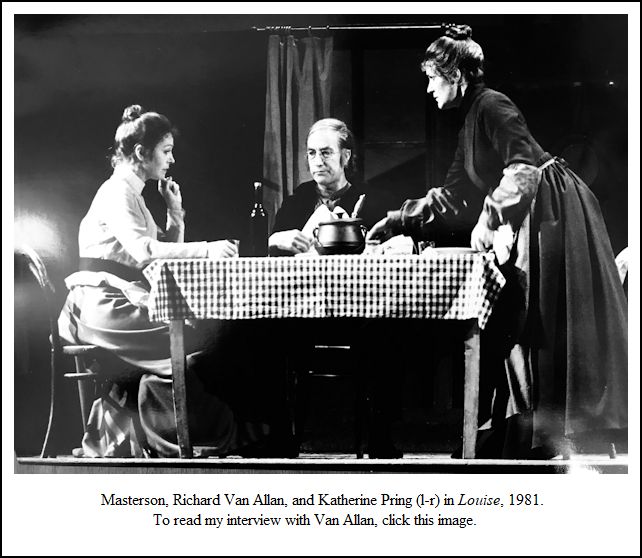

I usually think of that role as going to a mezzo.| Julien, ou La vie du poète

(Julien, or The Poet’s Life) is a poème lyrique or opera

by composer Gustave Charpentier. The work is devised in a prologue and

four acts and uses a French libretto by the composer. Julien is

a sequel to Charpentier's Louise (1900) and describes the artistic

aspirations of Louise’s suitor Julien. The opera premiered in Paris at

the Opéra-Comique on 4 June 1913. Like that of Louise, the plot of Julien is semi-autobiographical and requires many characters and chorus roles; in Julien, the female lead portrays four smaller characters in addition to the role of Louise. The opera integrates elements of an earlier composition, La Vie du Poète, a symphony-drama of 1888–1889. The chorus consists largely of filles du rêve ("girls of the dream"), fairies, and chimeras as well as various men's roles, mainly different kinds of working-class men. Charpentier stated that, except in the prologue, "Louise and the various characters who surround Julien are not so much real people as an exteriorized realization of their inner souls". The opera was not well received at its premiere, although it did gain Gabriel Fauré's admiration for its expressionist qualities. Apart from two productions in 1914, one of which was at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City with Geraldine Farrar and Enrico Caruso in the main roles, it had not been revived until 3 December 2000, when it had its German premiere. |

Masterson: Obviously as a singer, because I work terribly

hard at it. But it is interesting that along the way, and in

the very beginning, I could easily have gone into straight theater.

At one point in my life I would have liked that, and in the course

of my career, I have discussed in three countries the possibility to

do a straight play. I feel it could only help me on stage as

an actress. We get so little time to develop that side.

We just have to do it on instinct, and hope the producer will help us

through. We spend most of our time concentrating on the voice and

the music. If I was stretched by a dramatic part, it would give me

more equipment on stage.

Masterson: Obviously as a singer, because I work terribly

hard at it. But it is interesting that along the way, and in

the very beginning, I could easily have gone into straight theater.

At one point in my life I would have liked that, and in the course

of my career, I have discussed in three countries the possibility to

do a straight play. I feel it could only help me on stage as

an actress. We get so little time to develop that side.

We just have to do it on instinct, and hope the producer will help us

through. We spend most of our time concentrating on the voice and

the music. If I was stretched by a dramatic part, it would give me

more equipment on stage.

BD: Do you listen to your own records?

BD: Do you listen to your own records? BD: Have you ever wanted to stop singing and just

be a housewife, or grow vegetables in your yard?

BD: Have you ever wanted to stop singing and just

be a housewife, or grow vegetables in your yard? BD: We’ve talked a bit about

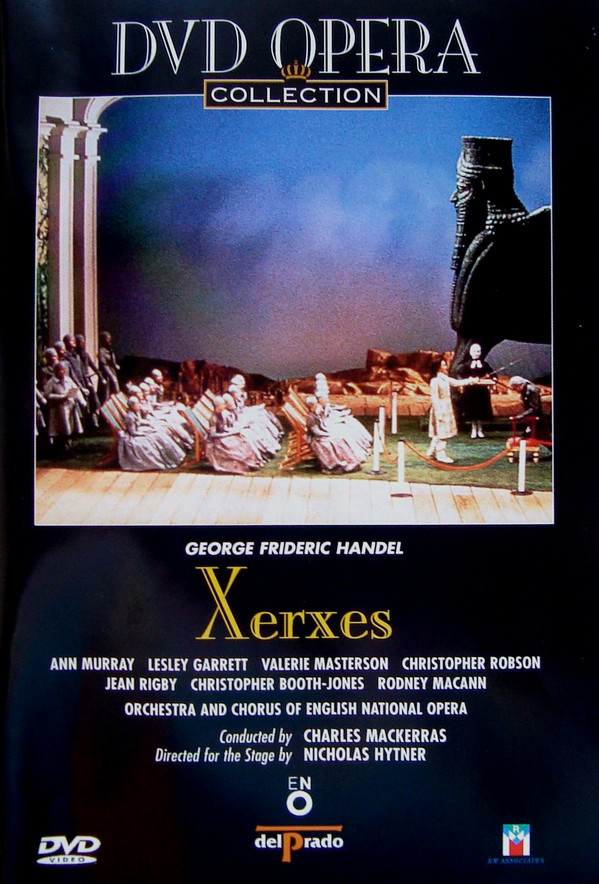

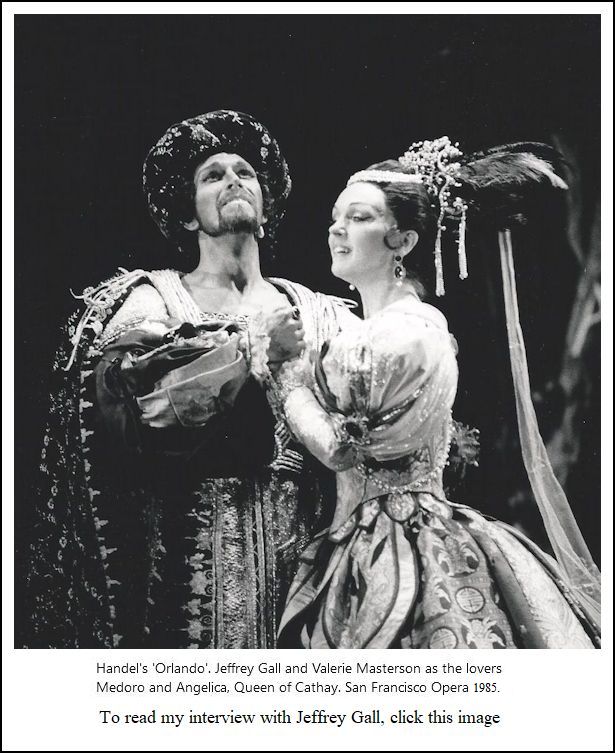

Handel, so let’s go back further to Monteverdi. Do you find

that music grateful for the voice?

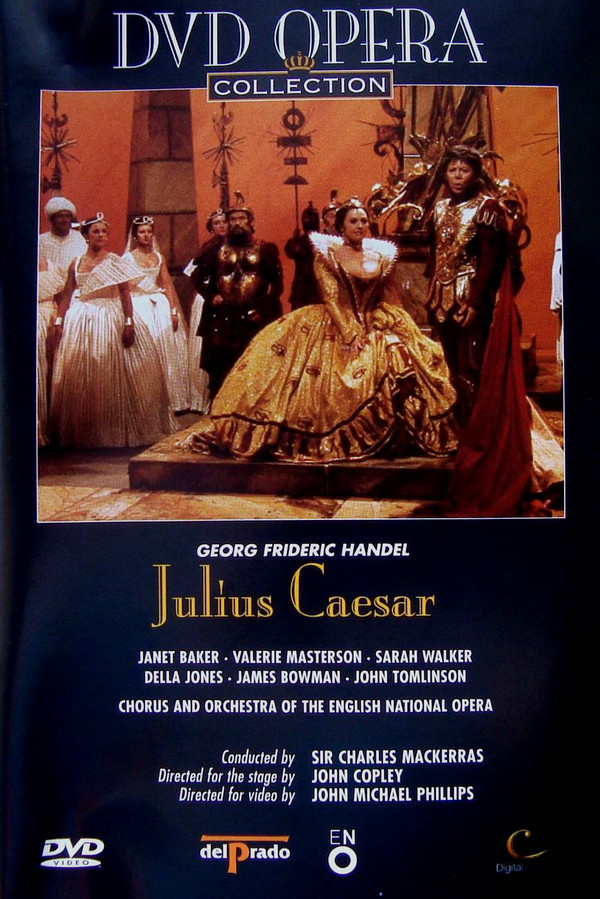

BD: We’ve talked a bit about

Handel, so let’s go back further to Monteverdi. Do you find

that music grateful for the voice? BD: Tell me about Konstanze.

BD: Tell me about Konstanze. BD: Coming back to Handel, when doing the three-part

arias, do you ever want a little TV screen placed downstage, that had

the score, just to keep track of where you are?

BD: Coming back to Handel, when doing the three-part

arias, do you ever want a little TV screen placed downstage, that had

the score, just to keep track of where you are?

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on September 28, 1982. Much of it was transcribed and published in the Massenet Newsletter in January, 1985. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1987, and again in 1997. The rest was transcribed in 2020, and it all was posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.