A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

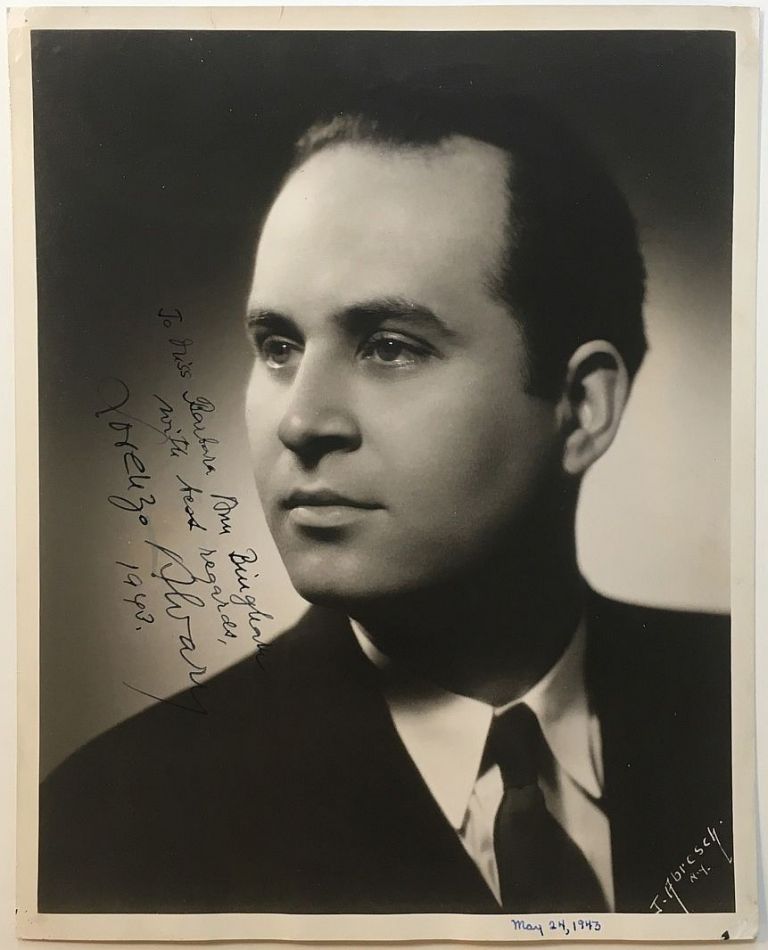

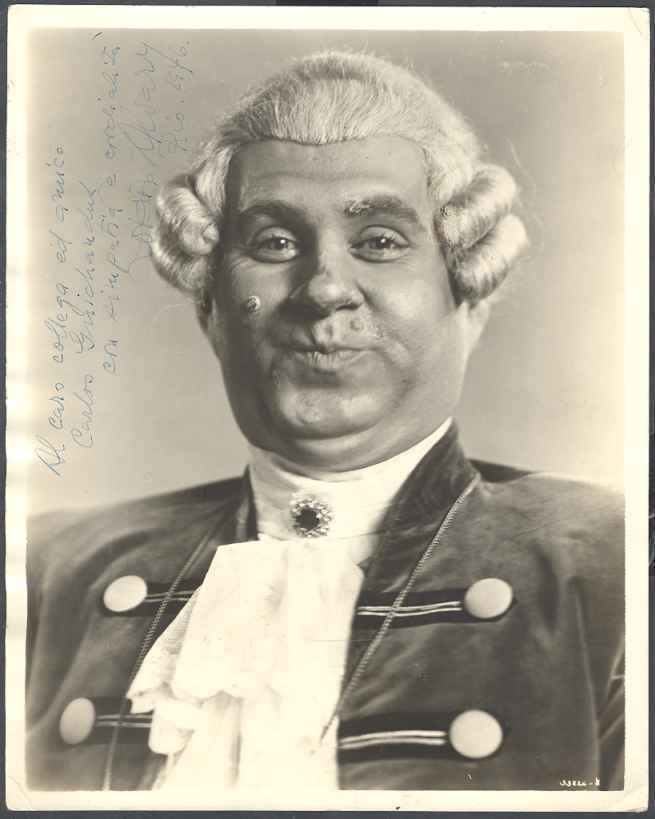

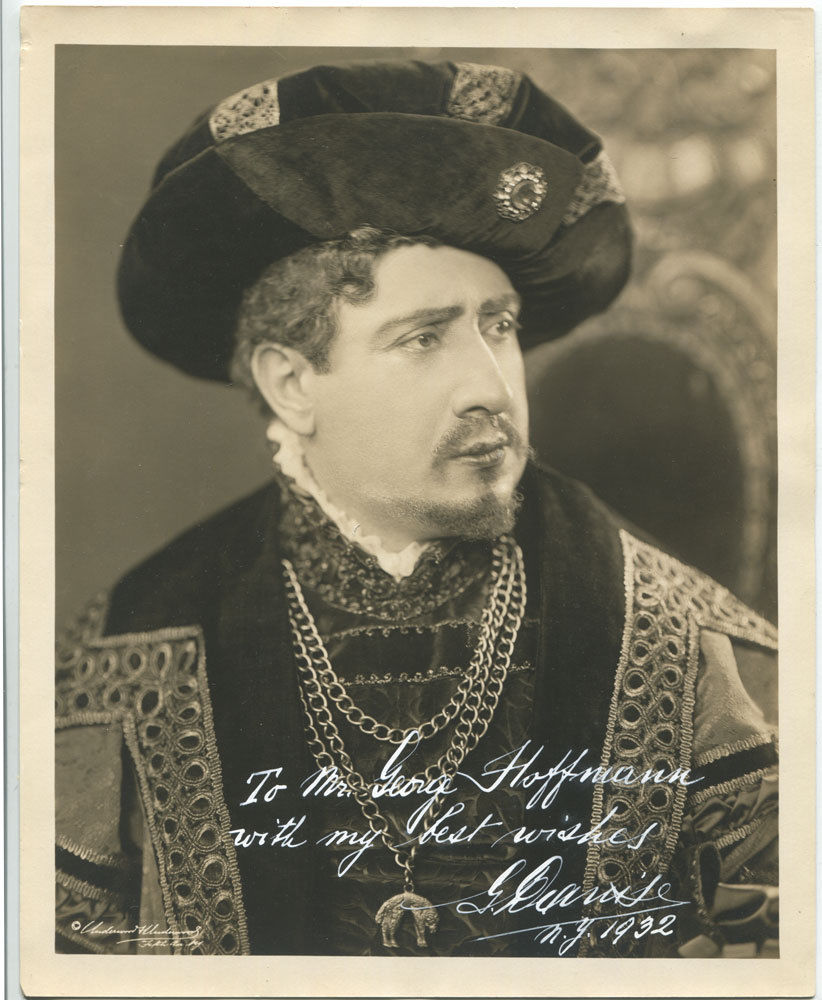

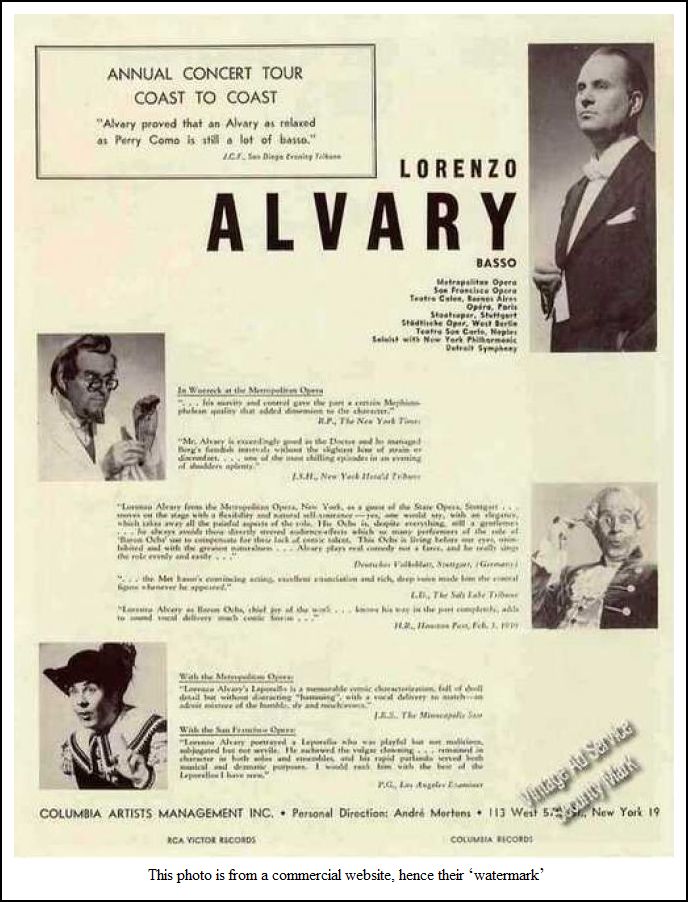

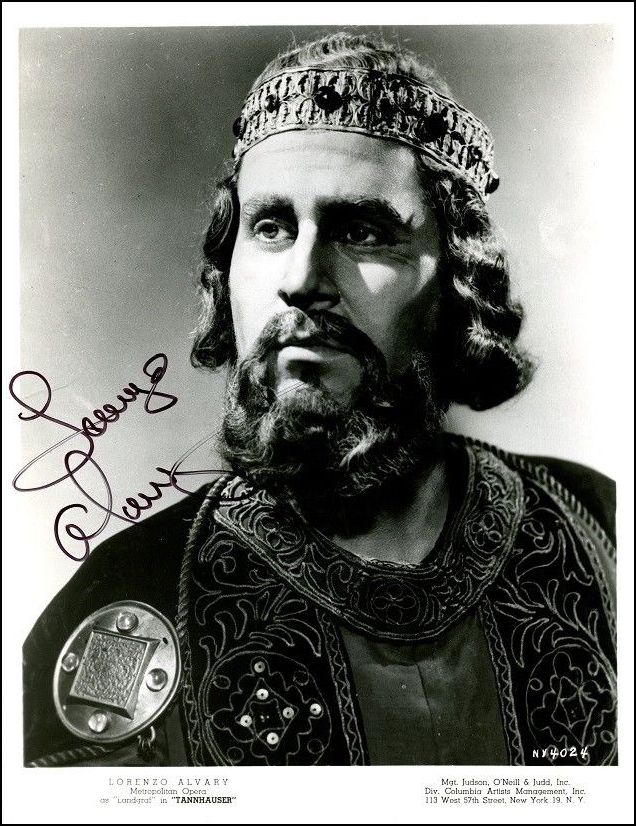

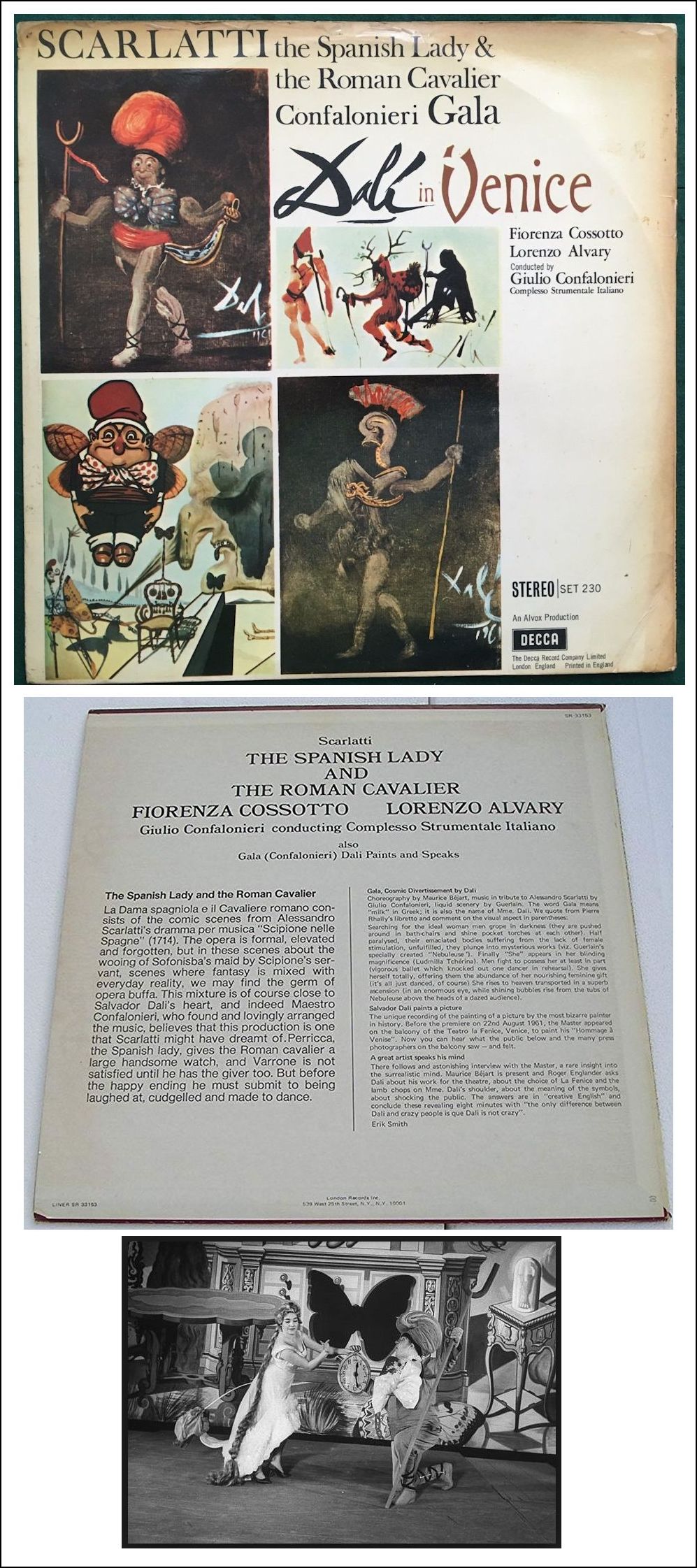

Lorenzo Alvary (February 20, 1909 – December 13, 1996) was a prolific singer and producer of many operas in the United States. Alvary was born in Debrecen, Hungary and studied law at the University of Budapest, but he quickly abandoned his law career to study music in Milan and Berlin. He first sang for the Vienna Staatsoper, but joined the Metropolitan Opera in 1942, where he remained on the roster for over twenty seasons. His most memorable roles are Baron Ochs in Rosenkavalier, Don Alfonso in Così Fan Tutte, and Leporello in Don Giovanni. Alvary was known for his elaborate costumes and for always playing characters that were less than attractive. He also sang for the San Francisco Opera. In 1972, he became the artistic director for the Miami Opera Guild and he received critical praise for his work with the company. Alvary started his own radio show entitled Opera Topics, which he hosted from 1964 – 1986. He went on to produce the surrealistic opera, The Spanish Lady and the Roman Cavalier, with Salvador Dali. As well as a career in the United States, Alvary had great international success. He went on to sing in over sixty operas in South America and Europe. He also appeared in many solo recitals, and in concerts with such directors as Bruno Walter and Arturo Toscanini. -- Lorenzo Alvary Papers, JPB 06-16. Music

Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

|

Bruce Duffie:

You’ve been a singer, you’re a director, you’re judging vocal

competitions, so tell me about all of the things you have to do

with opera.

Bruce Duffie:

You’ve been a singer, you’re a director, you’re judging vocal

competitions, so tell me about all of the things you have to do

with opera. BD: Please tell me about these seventeen things.

BD: Please tell me about these seventeen things. BD: It’s a war in the competitions. Is it also

a war in performance?

BD: It’s a war in the competitions. Is it also

a war in performance? LA: Not every judge has this idea, but I have this

idea. We are looking for people who can become professional

singers, and I always have only one thing in mind

— will this candidate be engaged? Is this candidate

ready to go into a theater and perform a role? This means that

out of the seventeen things, at least thirteen or fourteen have to be

there, because if thirteen or fourteen are not there, and only the voice

is there, then it won’t work. There is a certain level which that

person has to show, and especially is that person engageable?

This is the reason why the most important judges are managers.

Sometimes, someone gets the first prize, but the managers don’t believe

that person can be sold. Actually, everything has only a value

if people can use it for something, and an artist is a value in the

opera company.

LA: Not every judge has this idea, but I have this

idea. We are looking for people who can become professional

singers, and I always have only one thing in mind

— will this candidate be engaged? Is this candidate

ready to go into a theater and perform a role? This means that

out of the seventeen things, at least thirteen or fourteen have to be

there, because if thirteen or fourteen are not there, and only the voice

is there, then it won’t work. There is a certain level which that

person has to show, and especially is that person engageable?

This is the reason why the most important judges are managers.

Sometimes, someone gets the first prize, but the managers don’t believe

that person can be sold. Actually, everything has only a value

if people can use it for something, and an artist is a value in the

opera company.At this point, the first side of the forty-five minute cassette ran out, and I asked my guest if he wished to continue.

LA: This is a question I would like to answer, but I

don’t know. I ask myself the same question because it is not

true that opera can be fundamentally changed. That is not possible

because up to now, every time, every tentative change was negative.

Not only this, but you don’t even know if it going to be Boulez, or is it going

to be Richard Strauss who has to continue? Is it going to

be Stravinsky? Stravinsky, for me, is something colossal, or it

is going to be like Glass

and these people? I don’t know what people want. I know

only one thing — that the real opera lover

is very conservative. The real opera lover wants to hear a phrase,

wants to hear, for example, a very beautiful high C. For me, a

beautiful sound is the biological need, like food and many other things

which I use. I cannot stand cacophonic sounds because they disturb

me, probably because I was educated in the classical way. My mother

was a pianist, a Dohnányi pupil, and my father was a violinist.

He was a grocer, but also a violinist at the same time. I started

as a cellist, and I was a string quartet player before I started to sing.

But I don’t believe that the human voice lends itself for anything else.

I don’t say beautiful singing, but beautiful phrasing. For

example, the way Tebaldi phrases. Also, Licia Albanese. When

she sings that very difficult and very thankless role Michaela in Carmen,

she stole every show. Why? Because this is the bel

canto, and the bel canto can also be sung in Wagner. The

great Wagner singers also can sing bel canto, not with all

that shouting, yelling, or imitating an instrument with the voice.

The instrument should imitate the voice, not vice-versa.

So, I see a very dark period if we are not going to go back where we

were. But I don’t know if we have the talent to go back.

It’s very difficult to be a conservative, because the conservative has

to apply himself according to certain rules. But these people

now who are taking liberty, naturally overdo the liberty. Freedom

and liberty are only valuable if they are given in doses, not if they are

completely free and everybody can do whatever they want. So I see

it all very dark, and I am a great pessimist, I’m very sorry to say, and

very unhappy with what I hear.

LA: This is a question I would like to answer, but I

don’t know. I ask myself the same question because it is not

true that opera can be fundamentally changed. That is not possible

because up to now, every time, every tentative change was negative.

Not only this, but you don’t even know if it going to be Boulez, or is it going

to be Richard Strauss who has to continue? Is it going to

be Stravinsky? Stravinsky, for me, is something colossal, or it

is going to be like Glass

and these people? I don’t know what people want. I know

only one thing — that the real opera lover

is very conservative. The real opera lover wants to hear a phrase,

wants to hear, for example, a very beautiful high C. For me, a

beautiful sound is the biological need, like food and many other things

which I use. I cannot stand cacophonic sounds because they disturb

me, probably because I was educated in the classical way. My mother

was a pianist, a Dohnányi pupil, and my father was a violinist.

He was a grocer, but also a violinist at the same time. I started

as a cellist, and I was a string quartet player before I started to sing.

But I don’t believe that the human voice lends itself for anything else.

I don’t say beautiful singing, but beautiful phrasing. For

example, the way Tebaldi phrases. Also, Licia Albanese. When

she sings that very difficult and very thankless role Michaela in Carmen,

she stole every show. Why? Because this is the bel

canto, and the bel canto can also be sung in Wagner. The

great Wagner singers also can sing bel canto, not with all

that shouting, yelling, or imitating an instrument with the voice.

The instrument should imitate the voice, not vice-versa.

So, I see a very dark period if we are not going to go back where we

were. But I don’t know if we have the talent to go back.

It’s very difficult to be a conservative, because the conservative has

to apply himself according to certain rules. But these people

now who are taking liberty, naturally overdo the liberty. Freedom

and liberty are only valuable if they are given in doses, not if they are

completely free and everybody can do whatever they want. So I see

it all very dark, and I am a great pessimist, I’m very sorry to say, and

very unhappy with what I hear.

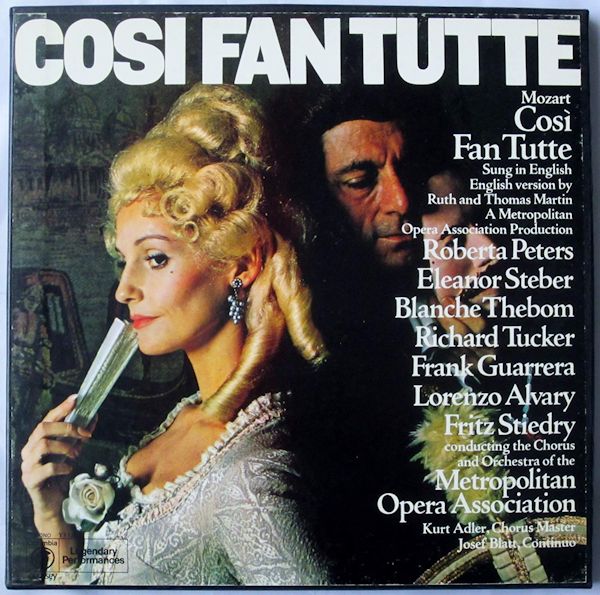

LA: That was a very special cast because, first of

all, we had one of the greatest stage directors who ever touched

opera, Alfred Lunt, so actually it was very easy to record because we

had been together so often. It went by itself, and Fritz Stiedry

was a very congenial conductor... not a great conductor, but a congenial

one. Many people have told me that it is a very excellent recording.

I did it also in Italian with Schwarzkopf, but I believe that this recording

with Eleanor Steber

is the best Fiordiligi who ever lived. I don’t know if you agree

with me...

LA: That was a very special cast because, first of

all, we had one of the greatest stage directors who ever touched

opera, Alfred Lunt, so actually it was very easy to record because we

had been together so often. It went by itself, and Fritz Stiedry

was a very congenial conductor... not a great conductor, but a congenial

one. Many people have told me that it is a very excellent recording.

I did it also in Italian with Schwarzkopf, but I believe that this recording

with Eleanor Steber

is the best Fiordiligi who ever lived. I don’t know if you agree

with me... LA: Yes!

LA: Yes!|

This recording of Così fan tutte is a souvenir of a memorable production that took place early in the tenure of Metropolitan Opera General Manager Sir Rudolph Bing. During that period, the Met and Bing, hoping to attract Broadway audiences, staged new productions of operetta and "light" opera. The performances featured English translations of the original librettos, and were directed by luminaries of the dramatic stage. December 20, 1950, the Met unveiled its new production of Johann Strauss' Die Fledermaus, directed by Garson Kanin. Mozart's Così fan tutte made its debut December 28, 1951, directed by Alfred Lunt, who also made an unforgettable cameo appearance at the start of each performance as a candle-lighting servant. The Met's sparkling new Così proved to be successful with both critics and audiences. The following June, the Met and Columbia Records joined forces to produce this recording. With the exception of Despina and Don Alfonso, the cast is identical to that of the Met premiere (in the recording Roberta Peters and Lorenzo Alvary replace Patrice Munsel and John Brownlee). There are many reasons why this cannot be the preferred recording of Mozart's masterpiece. First, any translation must, by definition, deprive us of Mozart's sublime wedding of music to the poetry of Lorenzo da Ponte's original Italian libretto. While for the most part Ruth and Thomas Martin's translation "sings" relatively well, it is still a matter of compromise as far as the delicate synthesis of text and music is concerned. Further, the translation contains more than its share of dated colloquialisms that, for me at least, grate upon repeated hearing. For example, Despina's admonition, "Paghiam, o femmine, d'ugual moneta questa malefica razza indiscreta" ("Ladies, pay in kind this impudent, evil breed"), becomes "Pay them in kind when they flirt and philander. Sauce for the goose is the same for the gander!" If that sort of thing bothers you, consider yourself forewarned. Other shortcomings include a modern piano as accompaniment for recitatives, and the lack of such stylistic considerations as appogiaturas and ornamentation. Further, there are several cuts in recitatives, as well as deletion of Ferrando and Dorabella's second-act arias. That said, there are many reasons why I would not want to be without this recording. It contains two outstanding performances -- Eleanor Steber's Fiordiligi and Richard Tucker's Ferrando. Steber was a renowned Mozart singer who, in addition to Fiordiligi, also sang the Countess, Donna Elvira, Pamina, and Donna Anna at the Met. The voice is rich, full, and beautiful throughout its range, and the florid requirements of the role pose no hurdles for Steber. Further, she masterfully portrays the pain the character experiences as, little by little, she succumbs to temptation. Tucker's masterful Ferrando may well come as more of a surprise. After all, this was a singer who made his greatest reputation in lirico-spinto and spinto roles. Even at this relatively early stage of his career Tucker had already sung such formidable roles as Enzo, Riccardo, Turiddu, Gabriele Adorno, Des Grieux, Cavaradossi and Don Carlo at the Met, as well as Radames in a concert performance with Toscanini. Tucker's voice certainly is more heroic than one would normally expect for Ferrando, but that is not necessarily a drawback, given the grace with which Tucker negotiates this demanding music. Tucker's identification with the role, enhanced by his superb diction, is also first-rate. It is unfortunate the production did not include Ferrando's second-act arias; as it is, Tucker's performance is a valuable memento of a great tenor who was too often taken for granted. The remainder of the cast, while not on this exalted level, is never less than acceptable. Neither Thebom nor Guarrera match the vocal splendor of their higher-voiced counterparts, but they are engaging, vital singers. The young Roberta Peters employs her bright tone and vivacious energy to good effect as Despina, although I wish she was consistent (one way or the other) in terms of rolling her "r's." Lorenzo Alvary, while not an outstanding vocalist, does winningly project Don Alfonso's insinuating nature. Fritz Stiedry's conducting is rather heavy-handed, but still provides reasonable support. The remastered monophonic sound is superb. K.M.-- Review from classicalcdreview.com

|

Lorenzo Alvary, Plaintiff-appellant, v. United States of America, Defendant-appellee, 302 F.2d 790 (2d Cir. 1962)Annotate this Case US Court of Appeals

for the Second Circuit - 302 F.2d 790 (2d Cir. 1962)

Argued December 14, 1961

|

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on March 21, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB later in the year, and again in 1989 and 1994. This transcription was made in 2018, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.