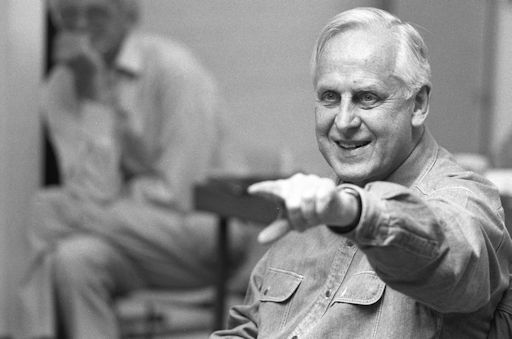

| Grammy and Tony Award-winning conductor John DeMain

(born January 11, 1944) is noted for his dynamic performances on concert

and opera stages throughout the world. American composer Jake Heggie assessed

the conductor’s broad appeal, saying, “There’s no one like John DeMain. In

my opinion, he’s one of the top conductors in the world.” In January 2023,

he received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Opera Association,

the NOA’s highest award.

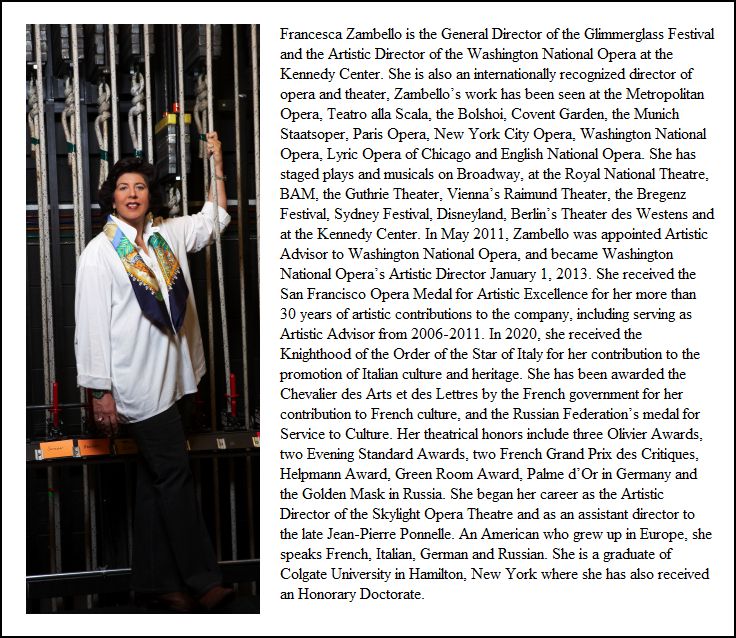

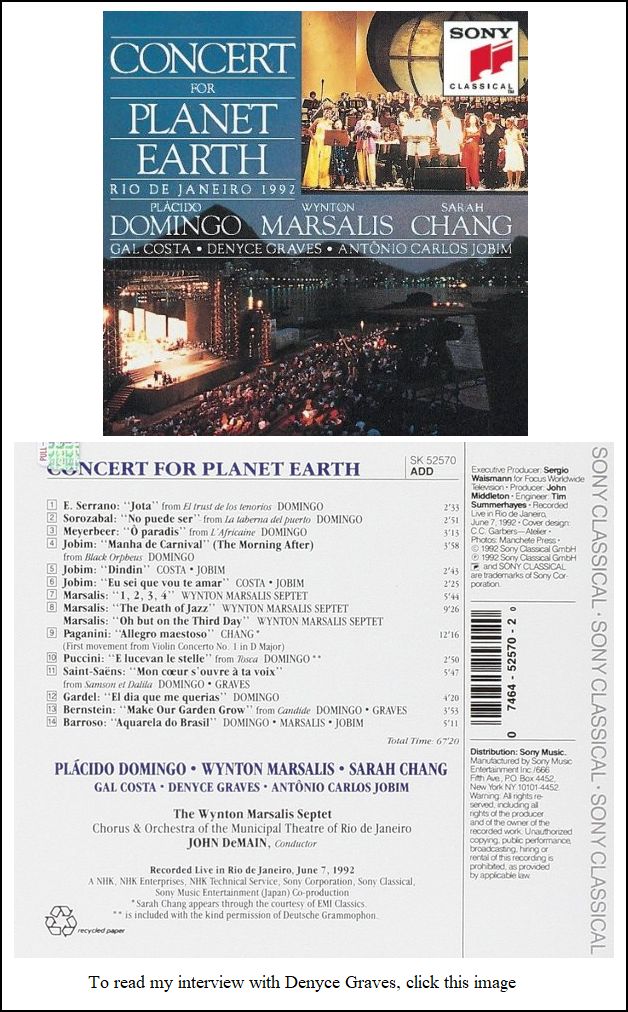

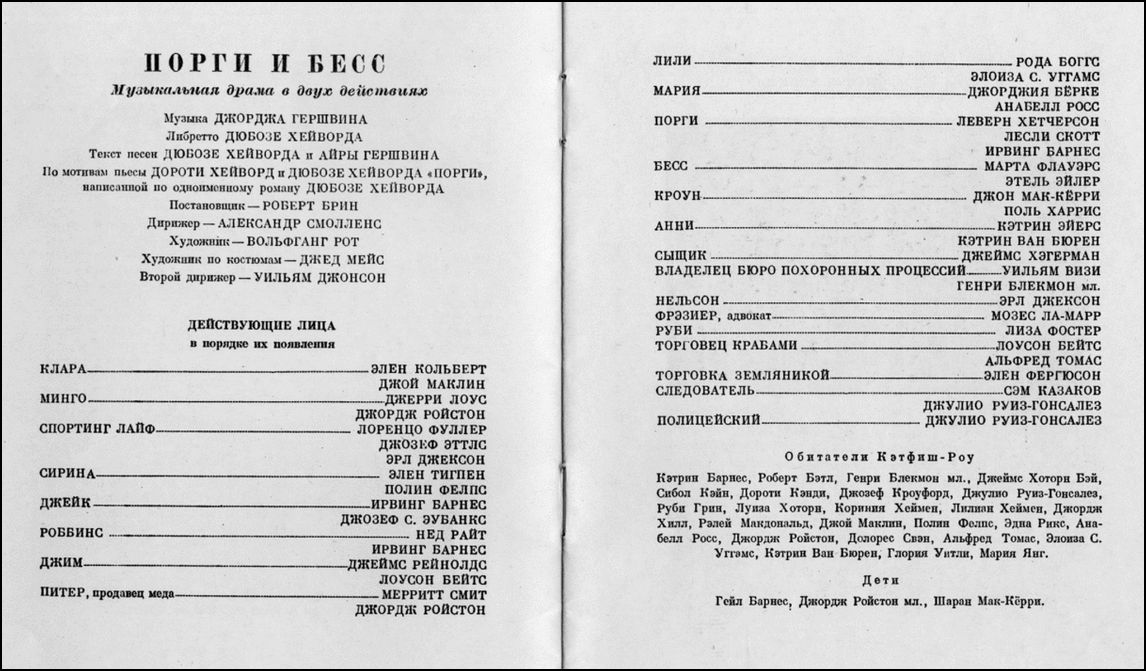

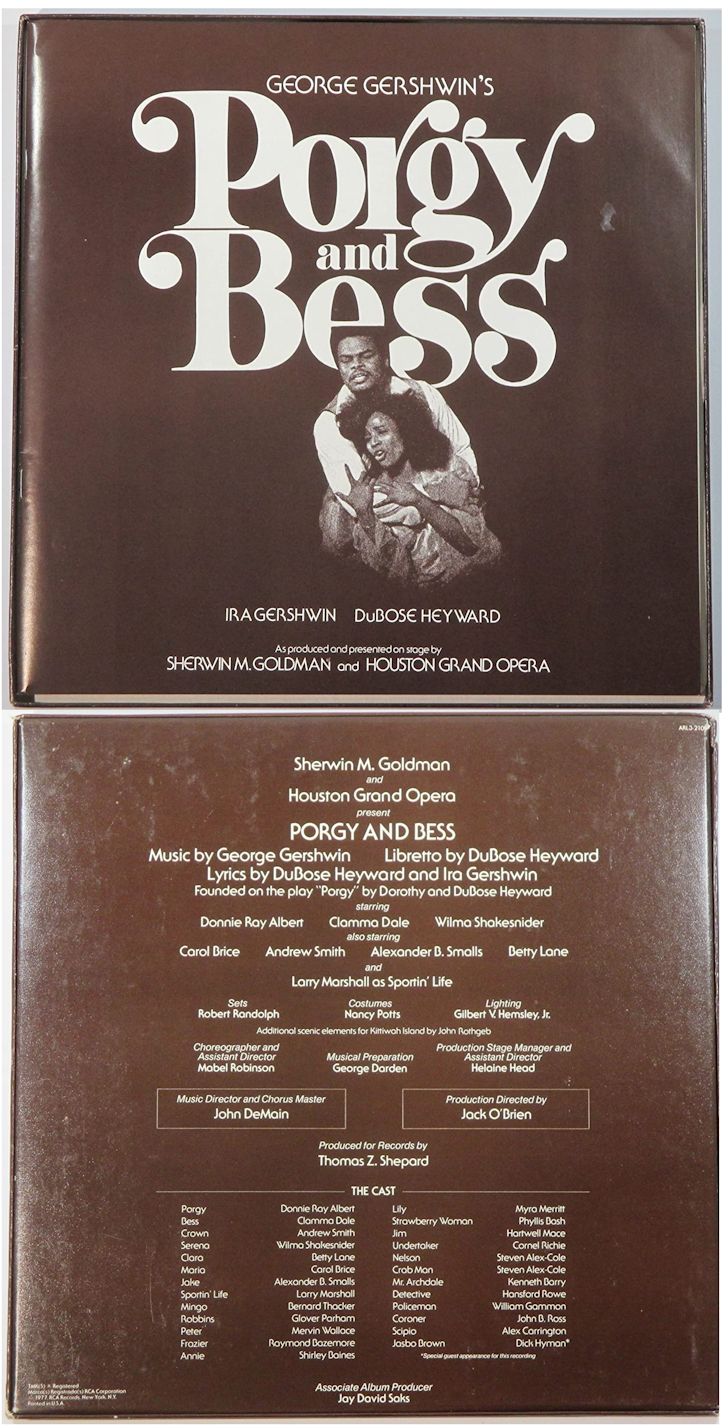

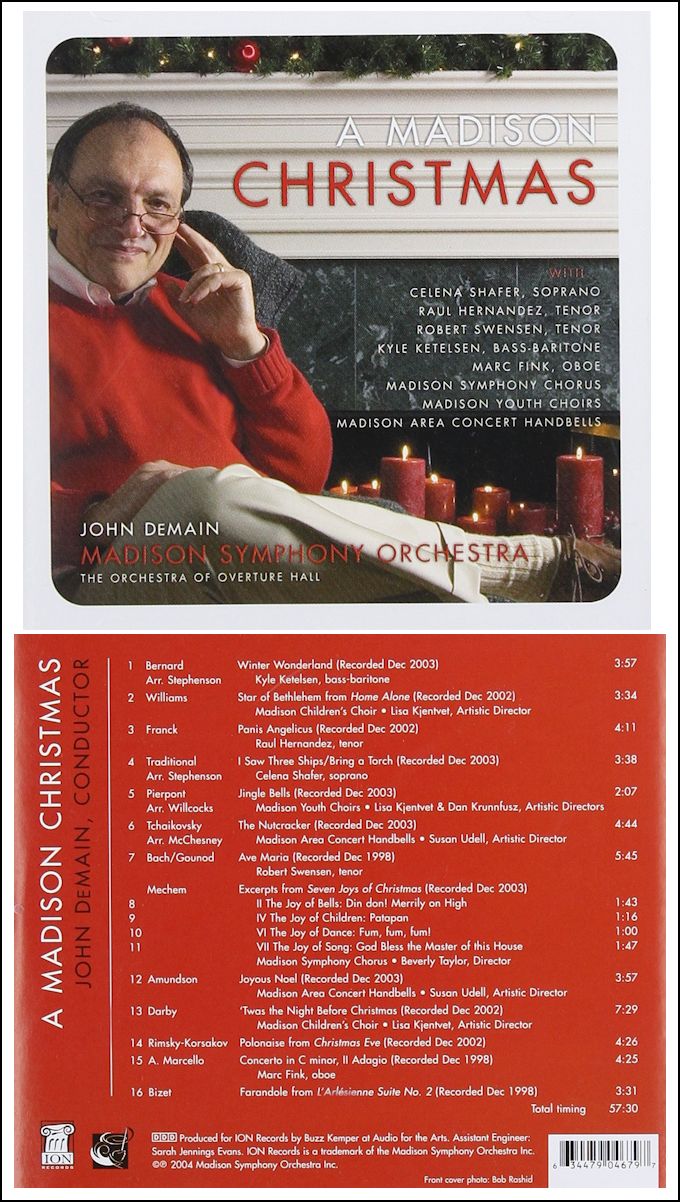

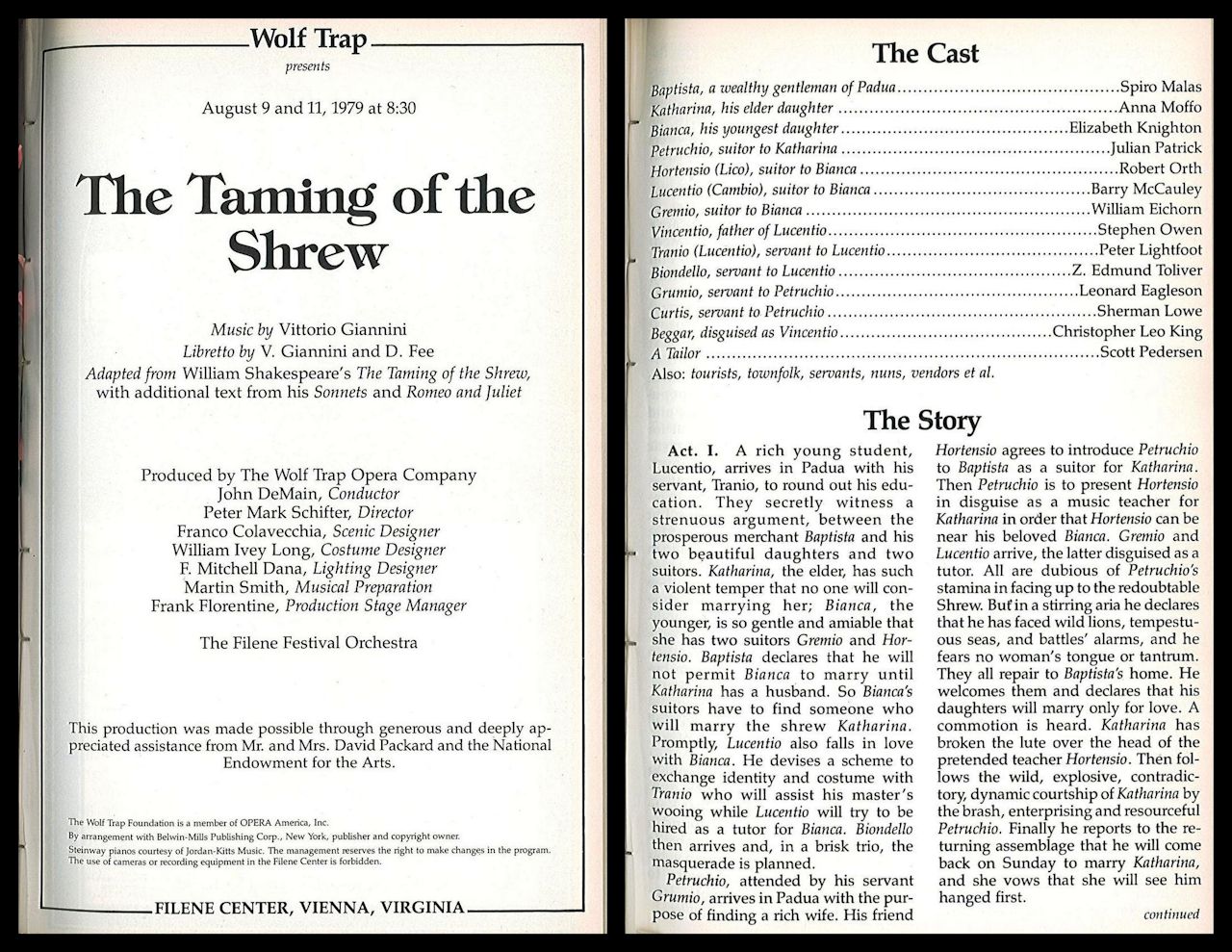

His active conducting schedule has taken him to the stages of the National Symphony, St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, the symphonies of Seattle, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Columbus, Houston, San Antonio, Long Beach, and Jacksonville, along with the Pacific Symphony, Boston Pops, Aspen Chamber Orchestra, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, London Sinfonietta, Orchestra of Seville, the Leipzig MDR Sinfonieorchester, and Mexico’s Orquesta Sinfónica Nacional. [Photo at right shows the young DeMain (right) working with Leonard Bernstein.] Prior engagements include visiting San Francisco Opera as guest conductor for General Director David Gockley’s farewell gala, Northwestern University to conduct Carlisle Floyd’s Susannah, and the Washington National Opera at the Kennedy Center in D.C. to conduct Kurt Weill’s Lost in the Stars. In 2019, he conducted the world premiere of Tazewell Thompson’s Blue at the Glimmerglass Festival to critical acclaim. The New York Times wrote that he “drew a vibrant performance from an orchestra of nearly 50 players; the cast was superb.” DeMain also serves as artistic director for Madison Opera. He has been a regular guest conductor with Washington National Opera at the Kennedy Center, and has made appearances at the Teatre Liceu in Barcelona, New York City Opera, Michigan Opera Theatre, Los Angeles Opera, Seattle Opera, San Francisco Opera, Virginia Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Aspen Music Festival, Portland Opera, and Mexico’s National Opera. During his distinguished 17-year tenure with Houston Grand Opera, DeMain led a history-making production of Porgy and Bess, winning a Grammy Award, Tony Award, and France’s Grand Prix du Disque for the RCA recording. In spring 2014, the San Francisco Opera released an HD DVD of their most recent production of Porgy and Bess, which he conducted. DeMain began his career as a pianist and conductor in his native Youngstown, Ohio. He earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at The Juilliard School, and made a highly-acclaimed debut with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. DeMain was the second recipient of the Julius Rudel Award at New York City Opera, and was one of the first six conductors to receive the Exxon/National Endowment for the Arts Conductor Fellowship for his work with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra. DeMain holds honorary degrees from the University of Nebraska and

Edgewood College, and he is a Fellow of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences,

Arts and Letters. He resides in Madison and his daughter, Jennifer, is

a UW–Madison graduate. == From the Madison Symphony Orchestra website

[slightly edited] |

|

Nunn has been nominated for the Tony Award for Best Direction of a Musical, the Tony Award for Best Direction of a Play, the Laurence Olivier Award for Best Director, and the Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Director of a Musical, winning Tonys for Cats, Les Misérables, and Nicholas Nickleby and the Olivier Awards for productions of Summerfolk, The Merchant of Venice, Troilus and Cressida, and Nicholas Nickleby. In 2008 The Telegraph named him among the most influential people in British culture. He has also directed works for film and television. In 2014, Nunn told The Telegraph that Shakespeare was his religion. "Shakespeare has more wisdom and insight about our lives, about how to live and how not to live, how to forgive and how to understand our fellow creatures, than any religious tract. One hundred times more than the Bible. I'm sorry to say that. But over and over again in the plays there is an understanding of the human condition that doesn't exist in religious books." |

|

Smallens was born in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and emigrated to the United States as a child, becoming an American citizen in 1919. He studied at the New York Institute of Musical Art until 1909, when he traveled to France to study at the Conservatoire de Paris. Returning to the United States, Smallens was a conductor or music director at several American music organizations including the Boston Opera Company (1911–1914), the Anna Pavlova Ballet Company (1917–1919), the Chicago Opera Company (1919–1923), the Philadelphia Civic Opera Company (1924–1930), the Philadelphia Orchestra (1928–1934) and the Radio City Music Hall (1947–1950). In addition, Smallens worked briefly on Broadway, conducting the premieres of Thomson's Four Saints in Three Acts in 1934 and Gershwin's Porgy and Bess the next year. (Both works were operas, not the musicals normally expected in Broadway theaters.) Smallens also conducted the Porgy and Bess revivals on Broadway in 1942 and 1953, as well as the famous 1952 world tour of the work, which culminated in that 1953 Broadway production. Smallens also conducted orchestras for music as part of several

documentary films in the late 1930s and early 1940s. He retired from music

in 1958 and moved to Sicily. In 1972, He died in Tucson, Arizona and is

buried there. |

© 2007 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on December 17, 2007. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.