|

Recognized worldwide as one of today’s most exciting vocal stars, Denyce Graves continues to gather unparalleled popular and critical acclaim in performances on four continents. USA Today identifies her as “an operatic superstar of the 21st Century,” and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution exclaims, “if the human voice has the power to move you, you will be touched by Denyce Graves.”

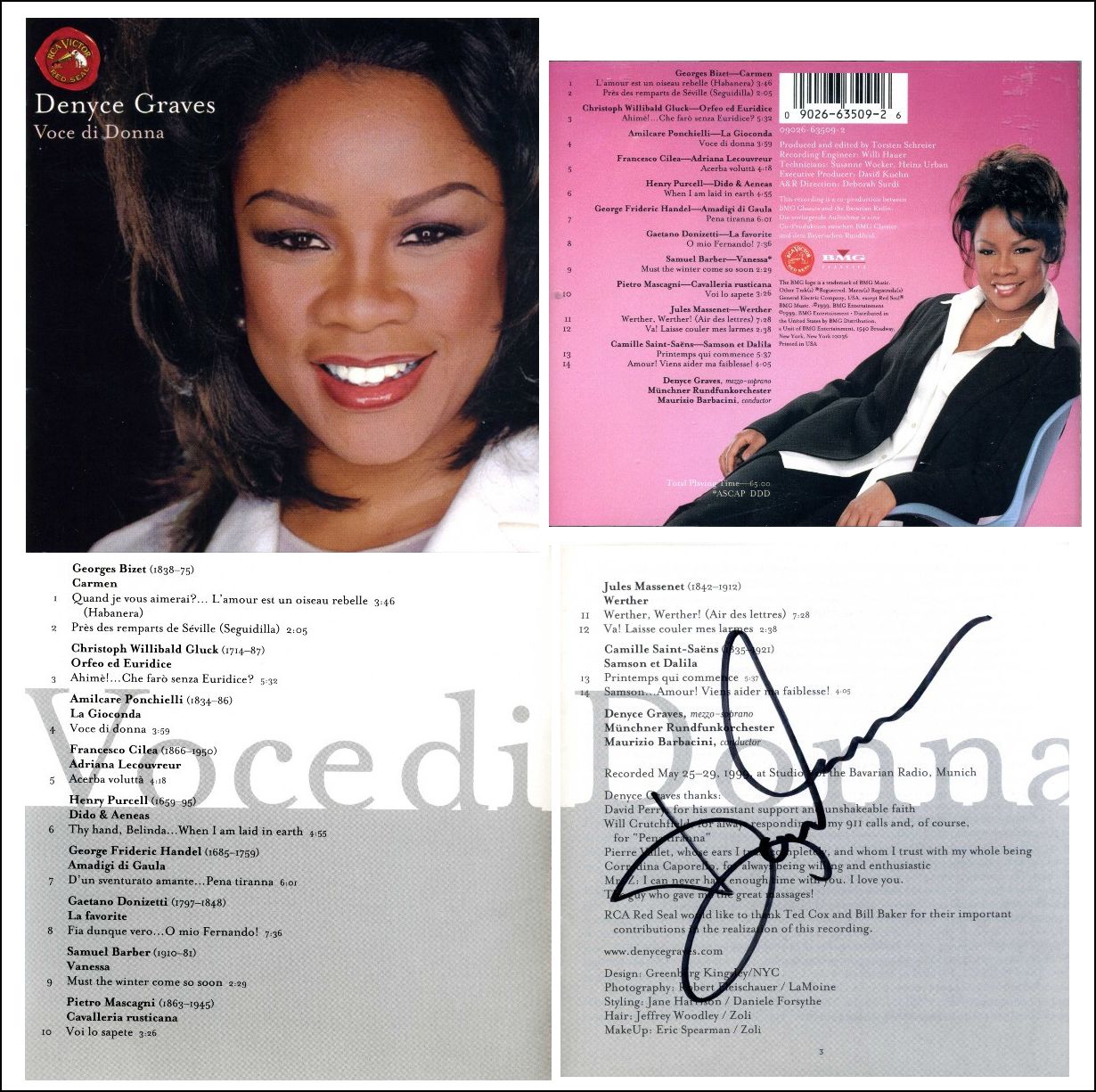

Graves’s 2012-13 season included two world premieres; she created the roles of Mrs. Miller in Minnesota Opera’s New Works Initiative commission of Doubt composed by Douglas J. Cuomo, and directed by Kevin Newbury, and of Emelda in Champion by Terence Blanchard at the Opera Theatre of St. Louis. The season also marked two role debuts for Graves as Herodias in Strauss’s Salome at Palm Beach Opera, and Katisha in Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado with the Lyric Opera of Kansas City. Graves makes numerous concert and recital performances including at Opera Carolina, Arizona Musicfest, National Philharmonic, San Diego Symphony, and several prestigious universities throughout the nation. As Graves’s dedication to teaching the singers of the next generation continues to be an important part of her career, she currently serves as the Rosa Ponselle Distinguished Faculty Artist at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore. Denyce Graves made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera in the 1995-96 season in the title role of Carmen. She returned the following season to lead the new Franco Zeffirelli production of this work, conducted by James Levine, and she sang the opening night performance of the Metropolitan Opera’s 1997-98 season as Carmen opposite Plácido Domingo. She was seen again that season as Bizet’s gypsy on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera for Domingo’s 30th Anniversary Gala, and she made her debut in Japan as Carmen, opposite the Don José of Roberto Alagna. Graves appeared in a new production of Samson et Dalila opposite Plácido Domingo at the Metropolitan Opera, and she performed Act III of this work opposite Mr. Domingo to open the Met’s season in 2005. She was partnered again with Mr. Domingo in the 1999 season-opening performances of this work for Los Angeles Opera. She was seen as Saint-Saëns’ seductress with Royal Opera, Covent Garden and The Washington Opera, both opposite José Cura – the latter under the baton of Maestro Domingo, as well as with Houston Grand Opera. Her debut in this signature role came in 1992 with the Chicago Symphony at the Ravinia Festival under the direction of James Levine and opposite Mr. Domingo and Sherrill Milnes, and she made a return engagement to the Festival in this same role in 1997. Graves appears continually in a broad range of repertoire with leading theaters in North America, Europe, and Asia. Highlights have included a Robert Lepage production of The Rake’s Progress at San Francisco Opera, the title role in Richard Danielpour’s Margaret Garner in the world premiere performances at Michigan Opera Theater with further performances at Cincinnati Opera, Opera Carolina, and the Opera Company of Philadelphia, the role of Charlotte in Werther for Michigan Opera Theater opposite the Werther of Andrea Bocelli in his first staged operatic performances, and Judith in a William Friedkin production of Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle in her return to Los Angeles Opera: she also has sung Judith at the Washington National Opera and for the Dallas Opera. Highlights of the mezzo-soprano’s other recent appearances include Azucena in Il trovatore, Nicklausse in Les contes d’Hoffmann, and Dulcinée in Massenet’s Don Quichotte with The Washington Opera; Giovanna Seymour in a new production of Anna Bolena for Dallas Opera; the title role in La Périchole with the Opera Company of Philadelphia; a rare double-bill of El amor brujo and La vida breve specifically mounted for her by Dallas Opera; Federica in the Metropolitan Opera’s new production of Luisa Miller, led by James Levine; and Amneris in Aida with Cincinnati Opera. Graves’s debut with the Théâtre Musical de Paris – Chatelet was as Baba the Turk in a Peter Sellars/Esa-Pekka Salonen production of The Rake’s Progress, and she returned to Covent Garden as Cuniza in Verdi’s Oberto after her debut performances as Carmen. Her debut at Teatro alla Scala was as the High Priestess in La vestale led by Riccardo Muti, and she soon returned as Giulietta in a new production of Les contes d’Hoffmann and as Mère Marie in the Robert Carsen production of Les dialogues des Carmélites. She appeared at Teatro Bellini in Catania in the title role of La favorita, and audiences in Genoa saw her first performances of Charlotte soon after her debut there as Carmen. Her debut in Austria came as Carmen with the Vienna Staatsoper, and she has also been seen in this role with Grand Théâtre de Genève, Genoa’s Teatro Carlo Felice, the Bregenz Festival, and festivals in Macerata, Italy and San Sebastian, Spain. Graves gave her first performances of Adalgisa in Norma for Opernhaus Zürich. Denyce Graves has worked with leading symphony orchestras and conductors throughout the world in a wide range of repertoire. She has performed with Riccardo Chailly, Myung-Whun Chung, Charles Dutoit, Christoph Eschenbach, James Levine, Zubin Mehta, Lorin Maazel, Kurt Masur, Riccardo Muti, and Mstislav Rostropovich. Graves has appeared with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Boston Symphony Orchestra, the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Houston Symphony, Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Orchestre Philharmonique de Monte-Carlo, and National Symphony Orchestra among a host of others. One of the music world’s most sought-after recitalists, Graves combines her expressive vocalism and exceptional gifts for communication with her dynamic stage presence, enriching audiences around the world. Her programs include classical repertoire of German lieder, French mélodie, and English art song, as well as the popular music of Broadway musicals, crossover and jazz together with American spirituals. For her New York recital debut, the New York Times wrote, “[h]er voice is dusky and earthy. She is a strikingly attractive stage presence and a communicative artist who had the audience with her through four encores.”

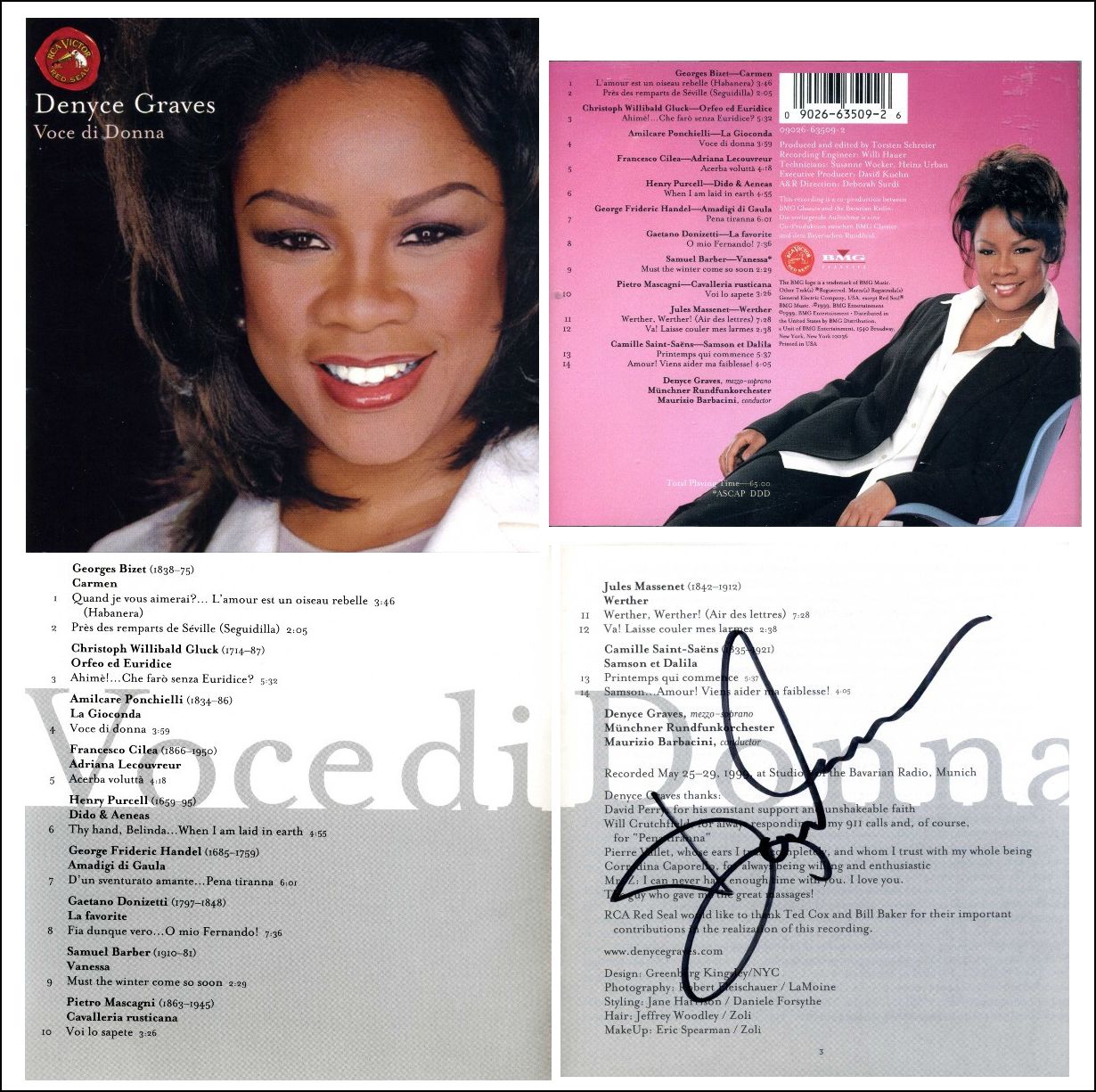

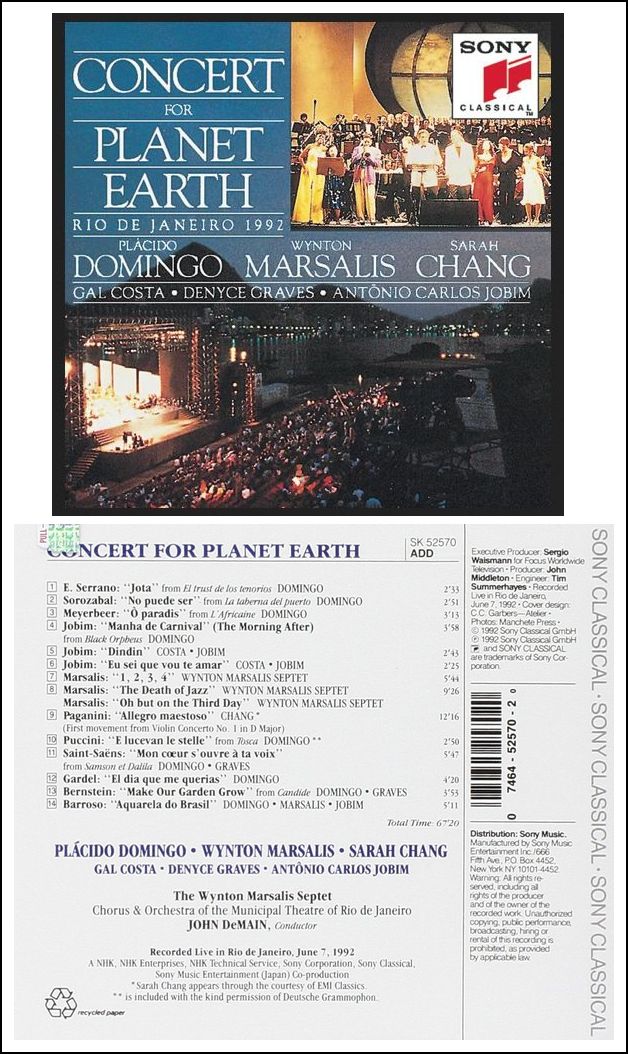

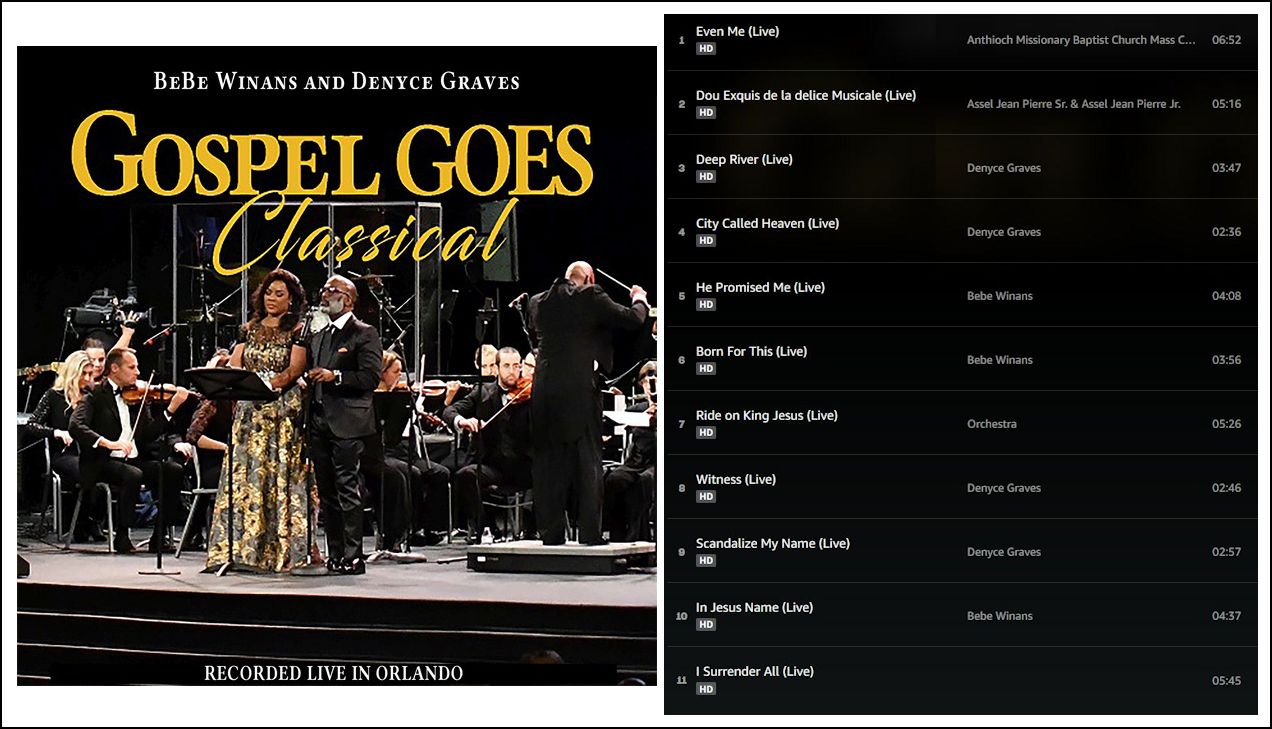

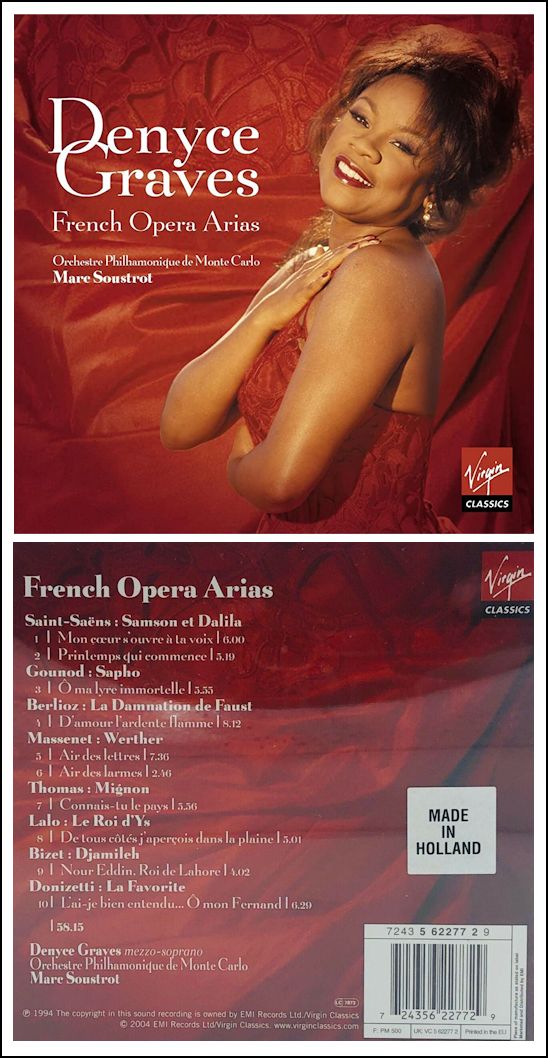

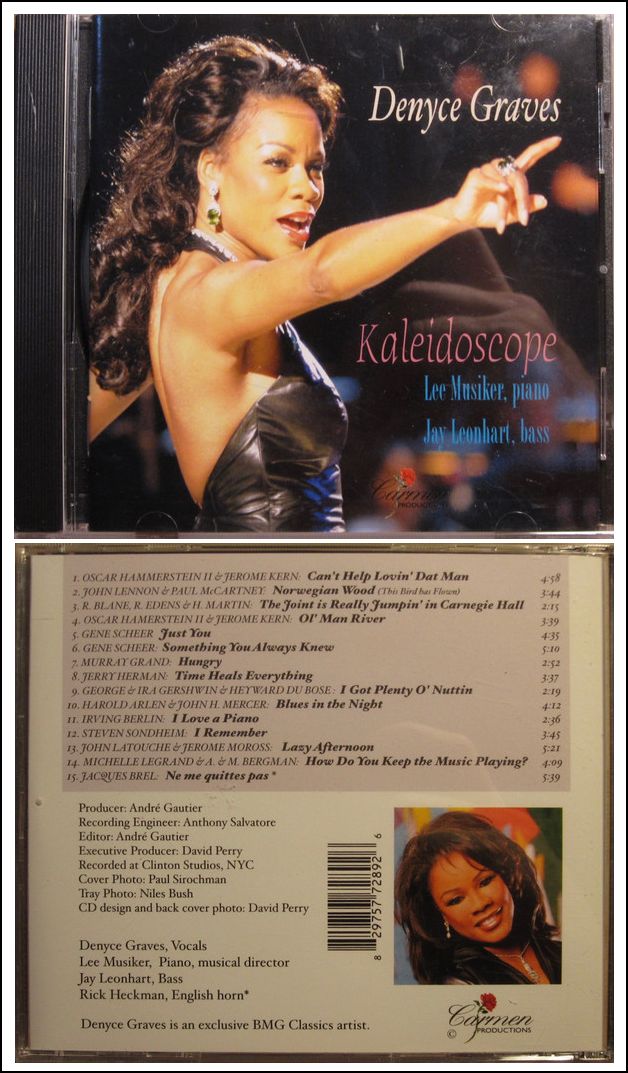

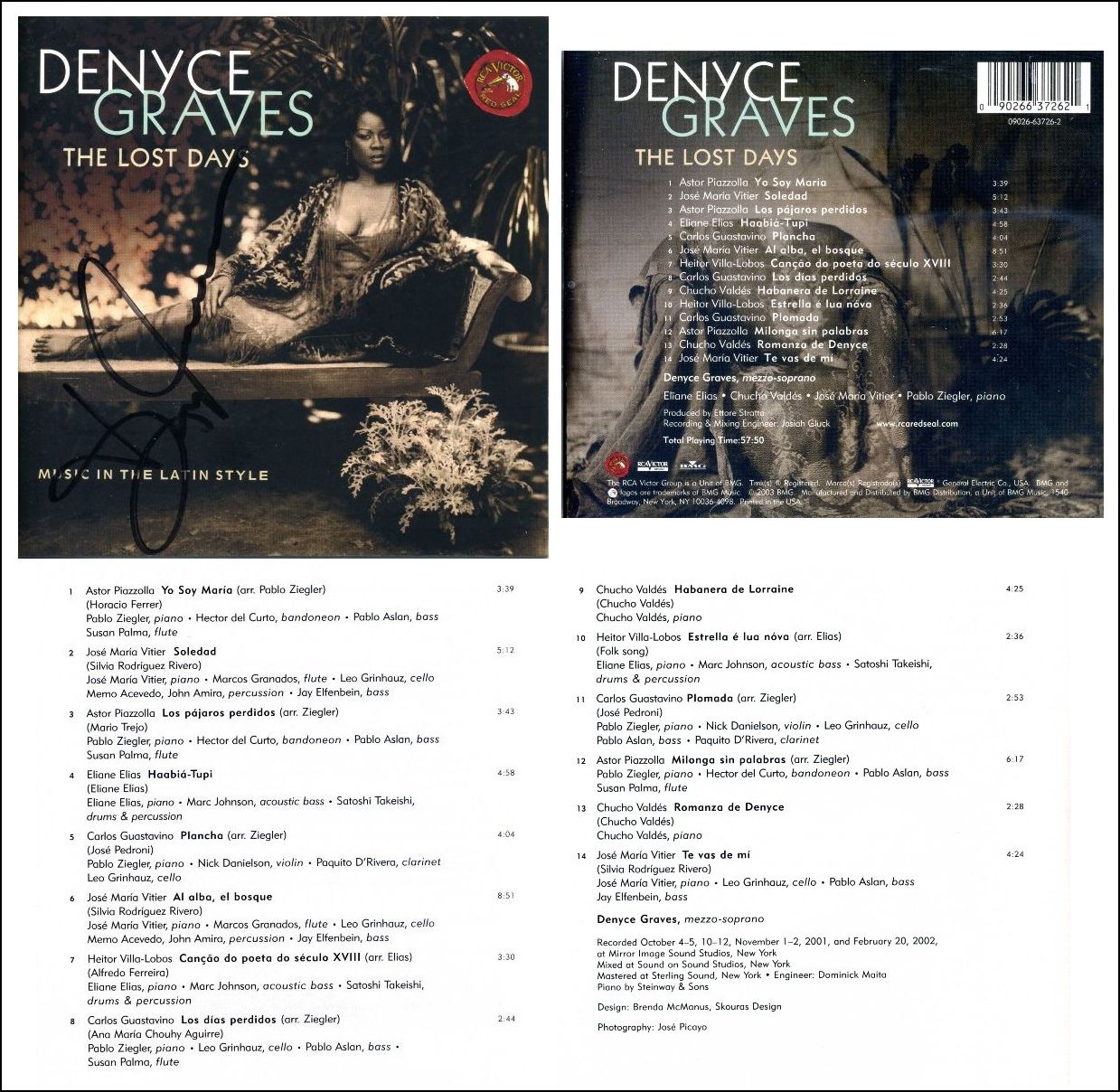

Graves appears regularly on radio and television as a musical performer, celebrity guest, and as the subject of documentaries and other special programming. In 1997 PBS Productions released a video and audio recording titled, Denyce Graves: A Cathedral Christmas, featuring Graves in a program of Christmas music from Washington’s National Cathedral. This celebration of music including chorus and orchestra is shown each year on PBS during the Christmas season. She was seen on the Emmy-award winning BBC special “The Royal Opera House,” highlighting Graves’s debut performances there, and in a program of crossover repertoire with the Boston Pops, which was taped for national television broadcast. In December 1999 Graves participated in a concert given at the Nobel Peace Prize Awards in Oslo, Norway which was televised throughout Europe. As the only classical music artist to be invited for this event, she performed selections from her RCA Red Seal release alongside performances by Sting, Paul Simon, Tina Turner and others. She has been a frequent guest on television shows including Sesame Street, The Charlie Rose Show, and Larry King Live. In 1996 she was the subject of an Emmy-award winning profile on CBS’s 60 Minutes. In 1999 Denyce Graves began a relationship with BMG Classics/RCA Red Seal. That same year Voce di Donna, a solo recording of opera arias, was released on RCA Red Seal. The Lost Days, a recording with jazz musicians of Latin songs in the Spanish and Portuguese languages, was released in January 2003. In June 2003 Church was released – this recording, developed by Denyce Graves, brings together African-American divas from various forms of music, all of whom were first exposed to music through their upbringing in church. Participants recorded music of their choice and include Dr. Maya Angelou, Dionne Warwick, En Vogue, Patti LaBelle, and others. Other recordings of Graves include NPR Classics’ release of a recording of spirituals, Angels watching over me, featuring the mezzo-soprano in performance with her frequent partner, Warren Jones and an album of French arias, Héroïnes de l’Opéra romantique Français, with the Orchestre Philharmonique de Monte-Carlo under Marc Soustrot. Her full opera recordings include Gran Vestale in La vestale, recorded live from La Scala with Riccardo Muti for Sony Classical; Queen Gertrude in Thomas’s Hamlet for EMI Classics; Maddalena in Rigoletto with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra under James Levine; and Emilia in Otello with Plácido Domingo and the Opéra de Paris, Bastille Orchestra under Myung-Whun Chung, both for Deutsche Grammophon. Denyce Graves is a native of Washington, D.C., where she attended the Duke Ellington School for the Performing Arts. She continued her education at Oberlin College Conservatory of Music and the New England Conservatory. In 1998, Graves received an honorary doctorate from Oberlin College Conservatory of Music. She was named one of the “50 Leaders of Tomorrow” by Ebony Magazine and was one of Glamour Magazine’s 1997 “Women of the Year.” In 1999 WQXR Radio in New York named her as one of classical music’s “Standard Bearers for the 21st Century.” Denyce Graves has been invited on several occasions to perform in recital at the White House, and she provides many benefit performances for various causes special to her throughout each season. Denyce Graves has been the recipient of many awards, including the Grand Prix du Concours International de Chant de Paris, the Eleanor Steber Music Award in the Opera Columbus Vocal Competition, and a Jacobson Study Grant from the Richard Tucker Music Foundation. In 1991, she received the Grand Prix Lyrique, awarded once every three years by the Association des amis de l’opéra de Monte-Carlo, and the Marian Anderson Award, presented to her by Miss Anderson. In addition Graves has received honorary doctorates from Oberlin College, College of Saint Mary and Centre College. == Biography [text only] is from the website

of the Peabody Institute of Johns Hopkins University

== Names in this box, and below, refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

© 1997 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in suburban Chicago, at her hotel near the Ravinia Festival, on August 7, 1997. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 2001. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website early in 2023. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.