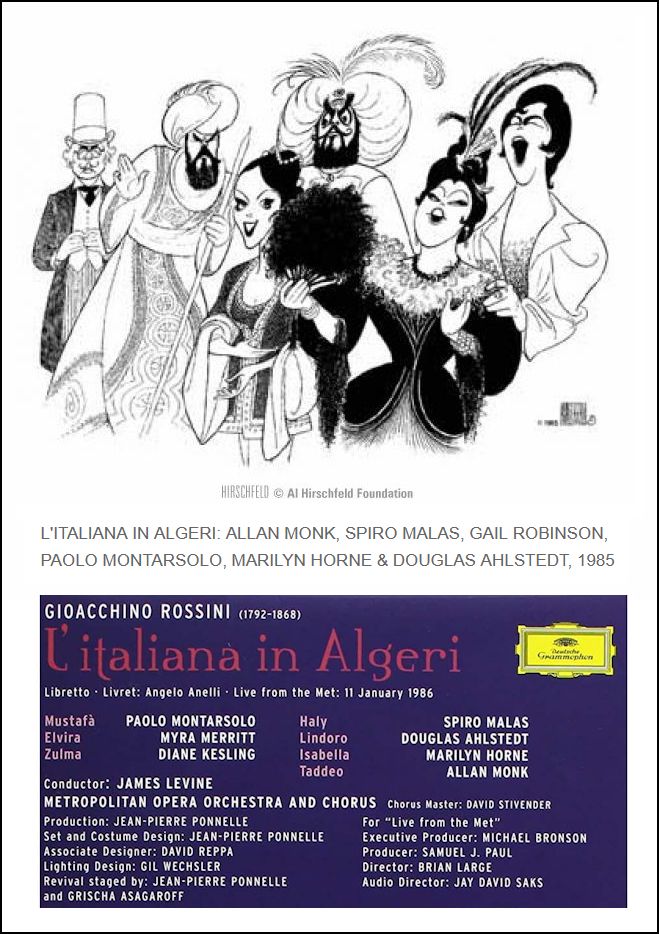

See my interviews with Paolo Montarsolo, Marilyn Horne, James Levine, and David Stivender

|

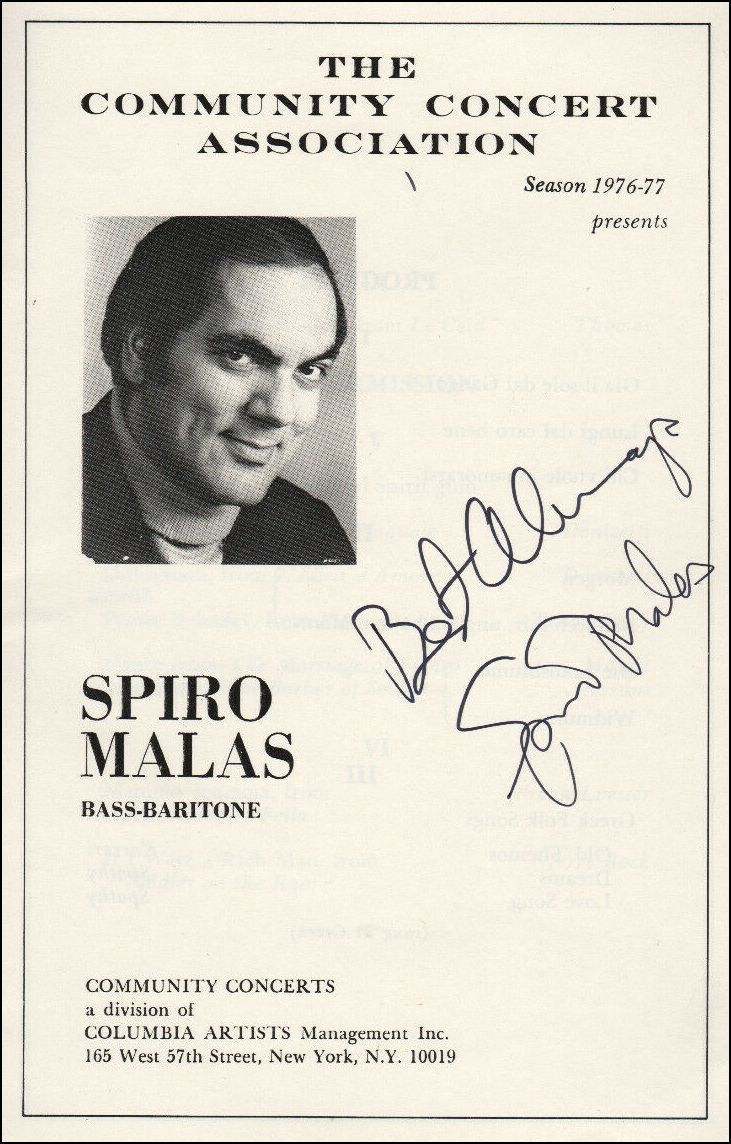

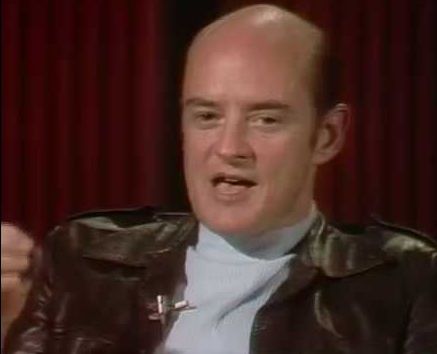

Spiro Malas (January 28, 1933 in Baltimore

- June 23, 2019 in New York City)

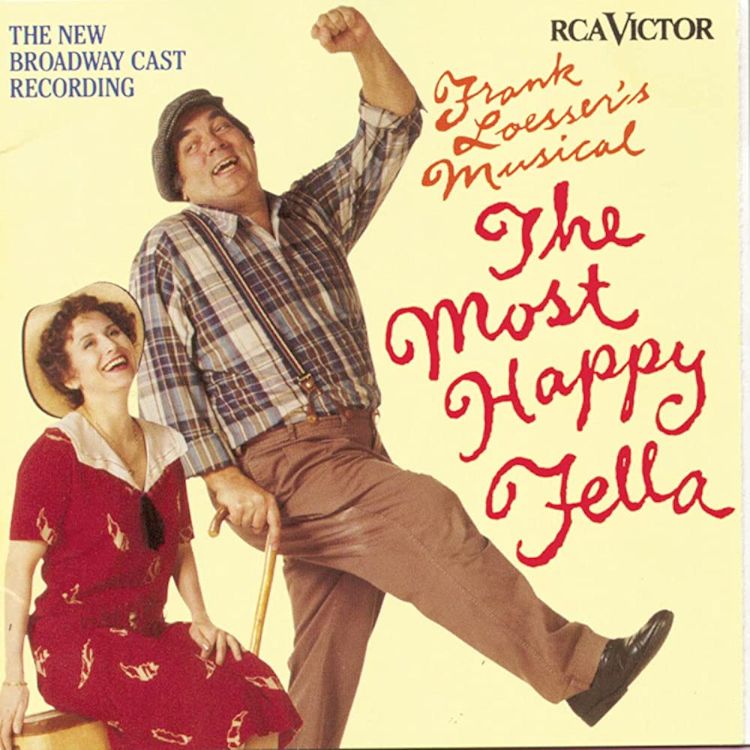

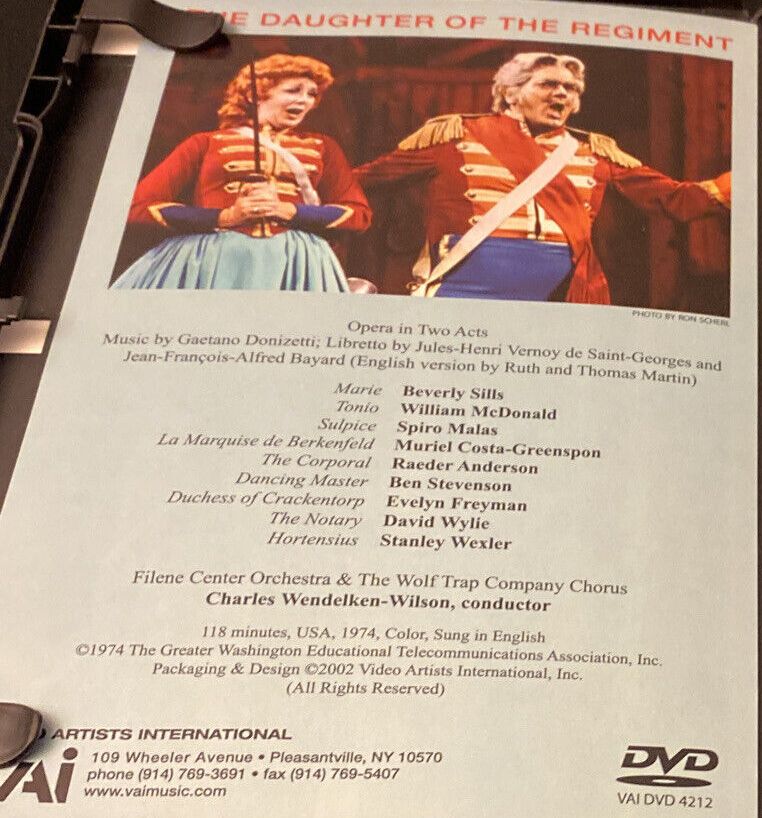

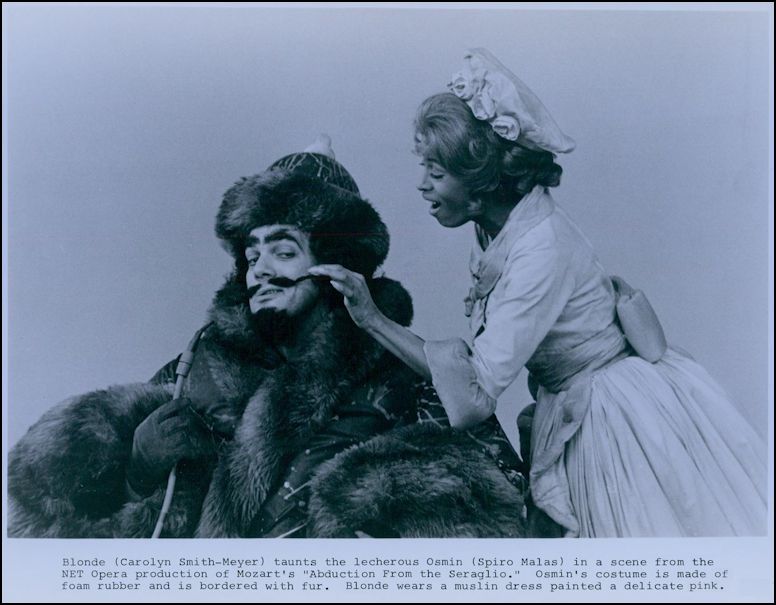

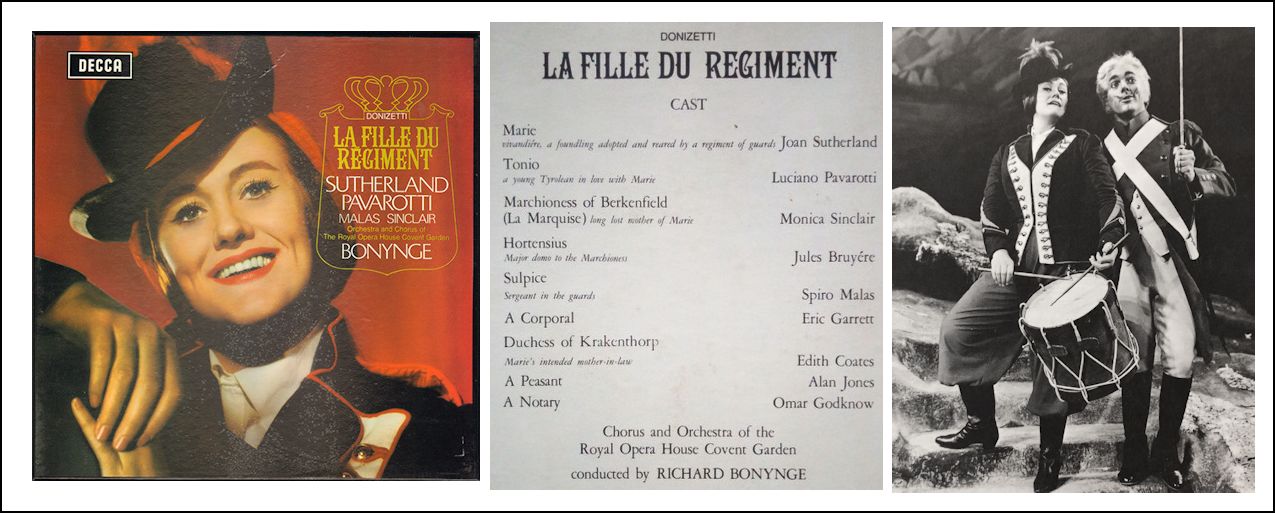

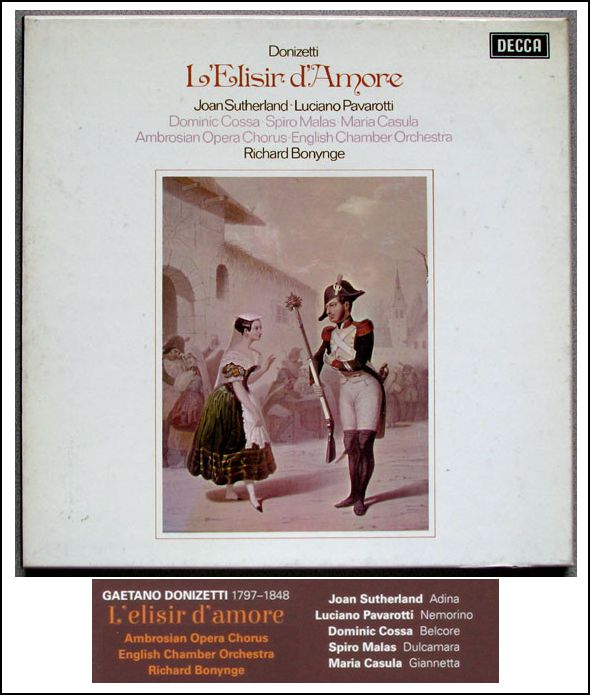

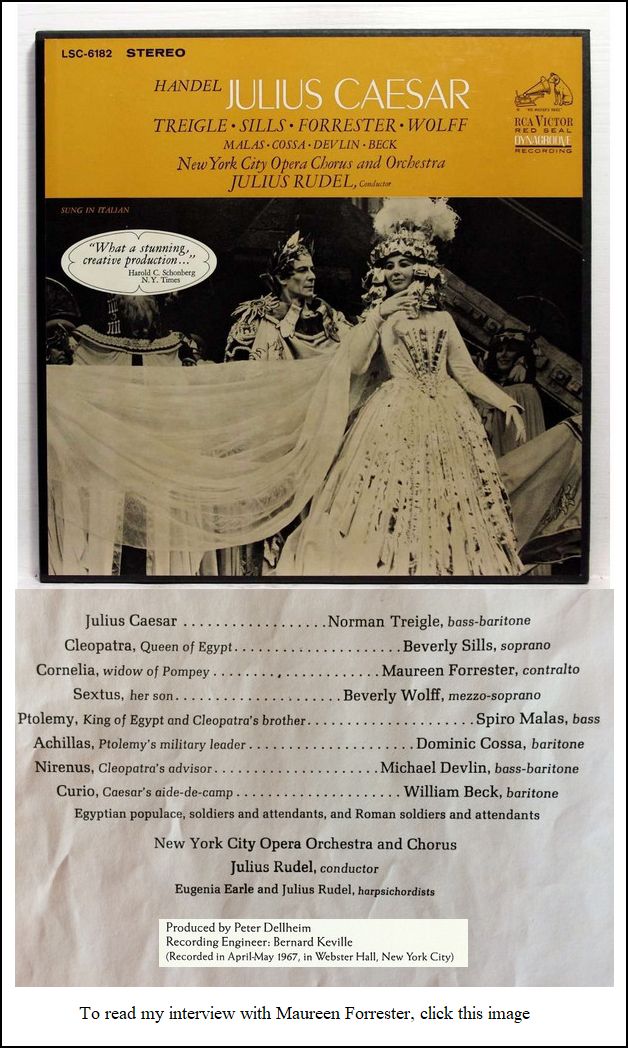

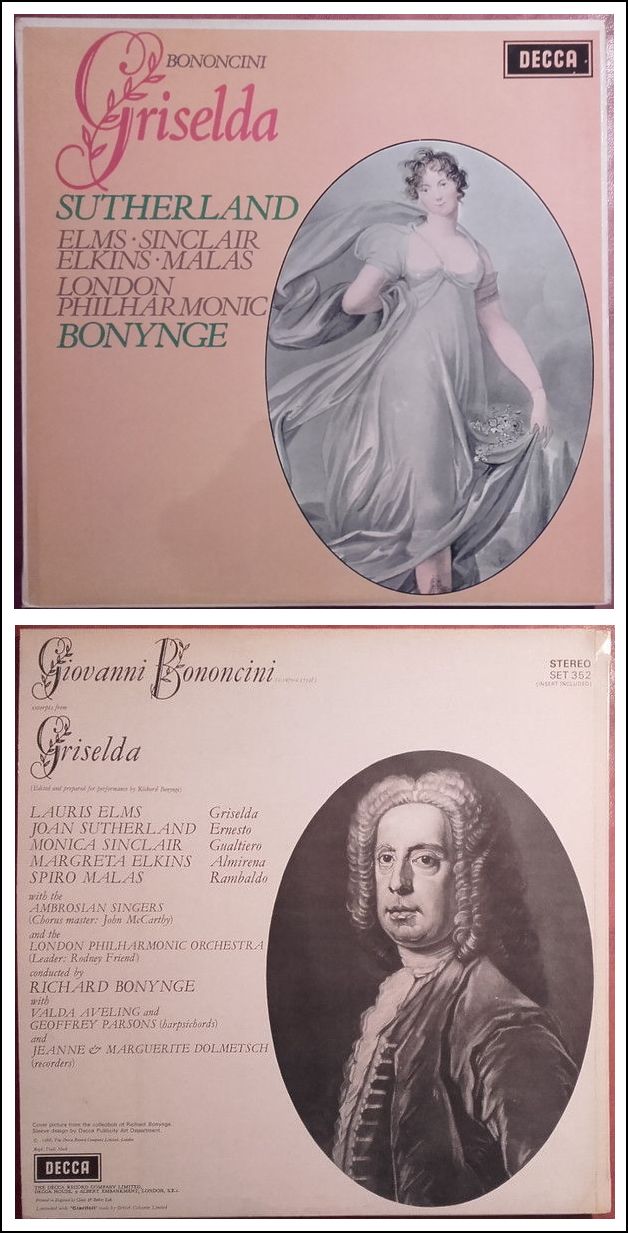

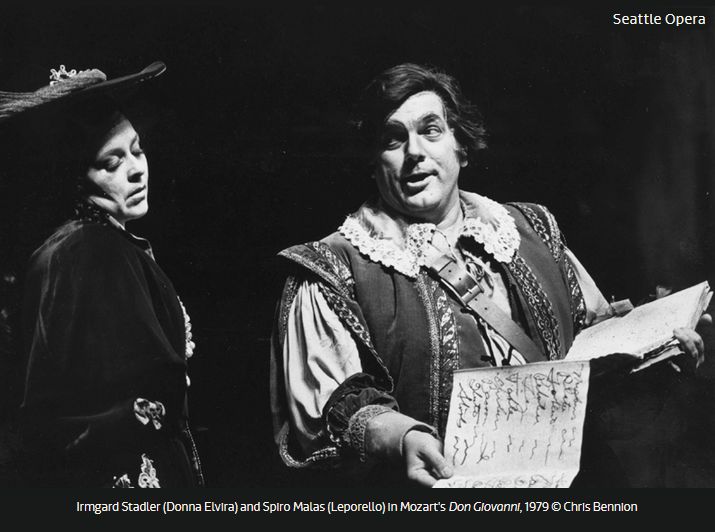

Spiro Malas, a stalwart at New York City Opera and the Metropolitan Opera, was celebrated for his acting ability. His voice was modestly scaled, but he used it cannily, always finding ways for voice and gesture to illuminate character. Malas’s family owned Duffy’s, a restaurant in Baltimore’s Southwest neighborhood. When he told his father he did not plan to join the business, the elder Malas staked him to four years of singing lessons. Malas attended Towson State College in Maryland and taught geography for a year after graduation while continuing his vocal training at Peabody Conservatory, where he caught the attention of Rosa Ponselle. In 1960, he was a winner at both the American Opera Auditions and the Met National Council Auditions. He made his City Opera debut as Spinelloccio in Gianni Schicchi that year and over the next two decades appeared in hundreds of performances with the company, in roles ranging from Mozart’s Figaro and Daland in Der Fliegende Holländer to General Boom in The Grand Duchess of Gerolstein, Don Magnifico in Cenerentola and King Dodon in Le Coq d’Or. He first worked with Joan Sutherland and Richard Bonynge in 1964, as Giorgio in I Puritani with Sarah Caldwell’s Boston Opera Group. His collaboration with the soprano–conductor team lasted many years and included a tour of Australia in 1965, the Decca recordings of Semiramide, La Fille du Régiment and L’Elisir d’Amore and the children's television series Who's Afraid of Opera? Although his career was largely based in the U.S., Malas appeared

at the Edinburgh Festival, Florence’s Maggio Musicale and the Salzburg

Festival. His Met debut came in 1983, when he joined Sutherland and Bonynge

for a Fille revival, as Sergeant Sulpice. He went on to appear

with the company 155 times over seven seasons in such roles as Frank in

Die Fledermaus, Capulet in Roméo et Juliette,

Zuniga in Carmen, the Police Commissioner in Der Rosenkavalier

and the Innkeeper in both Manon and Manon Lescaut.

Malas married mezzo-soprano Marlena Kleinman, a City Opera colleague,

on September 30, 1963, in a City Hall wedding that took place between opera

rehearsals. As Marlena Malas, she is now a celebrated voice teacher.

== Obituary by Fred Cohn

|

William Gormaly Ball (April 29, 1931 in Chicago – July 30, 1991

in Los Angeles) was an American stage director and founder of the American

Conservatory Theater (ACT). He was awarded the Drama Desk Vernon Rice Award

in 1959 for his production of Chekhov's Ivanov and was nominated

for a Tony Award in 1965 for his production of Molière's Tartuffe,

starring Michael O'Sullivan and René Auberjonois. He was also a noted

director of opera.

William Gormaly Ball (April 29, 1931 in Chicago – July 30, 1991

in Los Angeles) was an American stage director and founder of the American

Conservatory Theater (ACT). He was awarded the Drama Desk Vernon Rice Award

in 1959 for his production of Chekhov's Ivanov and was nominated

for a Tony Award in 1965 for his production of Molière's Tartuffe,

starring Michael O'Sullivan and René Auberjonois. He was also a noted

director of opera.Ball founded the American Conservatory Theater in Pittsburgh in 1965. This was a company of up to 30 full-time paid actors who studied all disciplines of the theater arts during the day and performed at night. Ball had a falling out with ACT's financial benefactors in Pittsburgh and took the company on the road. His 1966 productions of Albee's Tiny Alice, Pirandello's Six Characters in Search of an Author, and others at the Stanford University Summer Festival led a group of financiers to offer his company a home in San Francisco, which had recently lost the Actor's Workshop to New York's Lincoln Center. In its first season, Ball's ACT produced twenty-seven full-length

plays in two theaters over the course of seven months. Some actors

would do one role in the early part of a play at the Geary Theatre then

run two blocks up the hill to the Marines Memorial Theatre to appear in

the last part of another. Ball's 1974 production of Cyrano de Bergerac

and his 1976 production of The Taming of the Shrew were televised

nationally on PBS. In 1979, ACT received the Tony Award for excellence in

regional theatre. At the New York City Opera, from 1959 to 1964, Ball directed productions of Weisgall's Six Characters in Search of an Author (world premiere, with Beverly Sills), Mozart's Così fan tutte (with Phyllis Curtin), Egk's The Inspector General (with the composer conducting), Gershwin's Porgy and Bess (with Julius Rudel conducting), Britten's A Midsummer Night's Dream (with Tatiana Troyanos as Hippolyta), Mozart's Don Giovanni (with Norman Treigle in the title role), and Hoiby's Natalia Petrovna (world premiere). |

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on May 19,1982. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1987, 1989, 1990, 1993, 1997. and 1998. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.