|

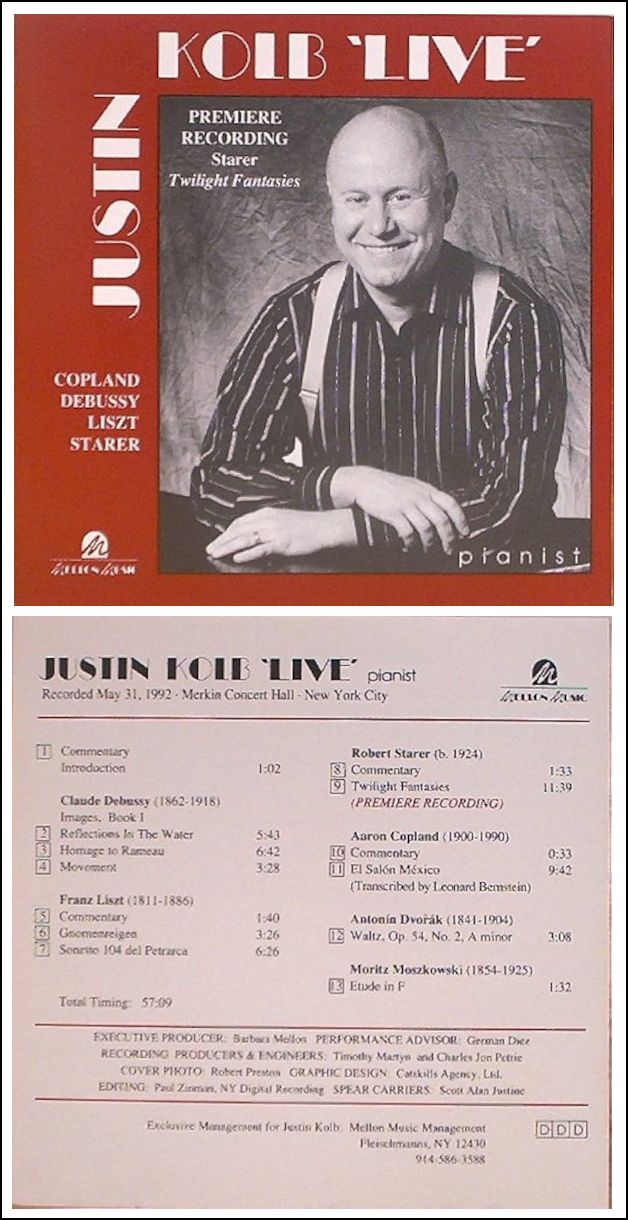

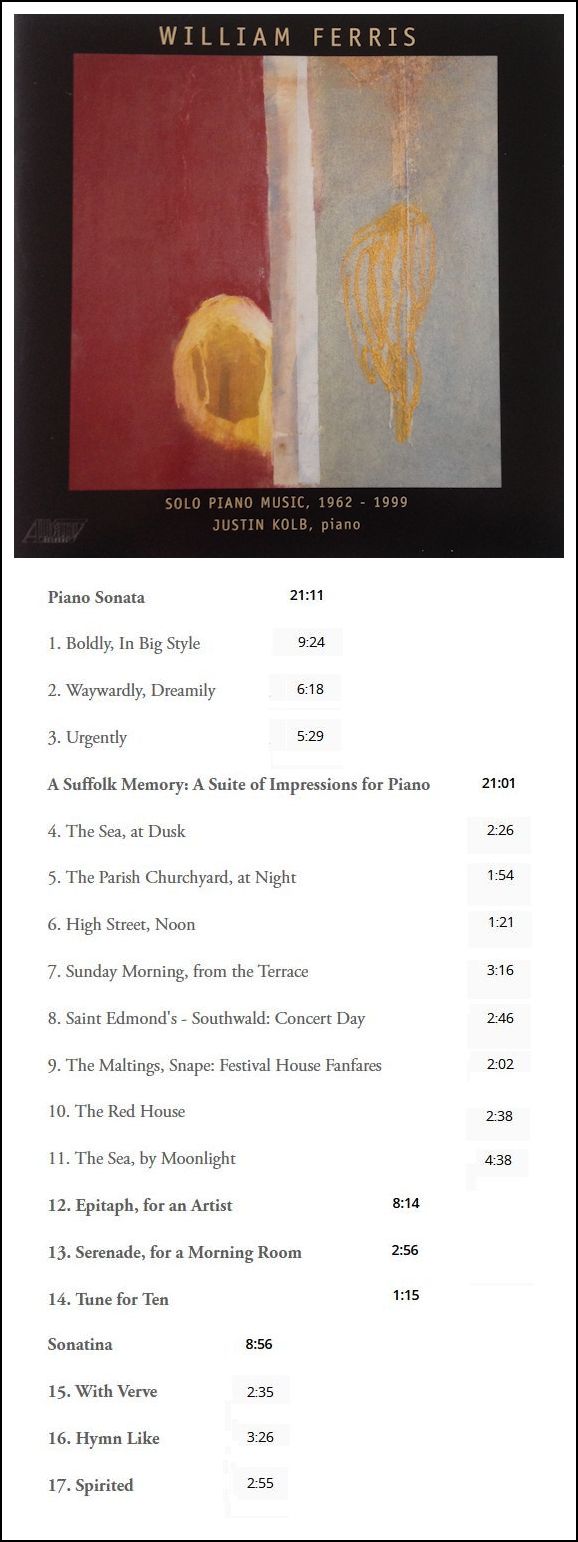

Justin Kolb’s recitals include lively commentary that is always

interesting and sometimes humorous. He enjoys programming music from the

traditional literature with music by living Americans — South, Central

and North — and Franz Liszt. A proponent of American music, Kolb frequently

performs the music of Joan

Tower, Tania León,

Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber, and Peter Schickele. His

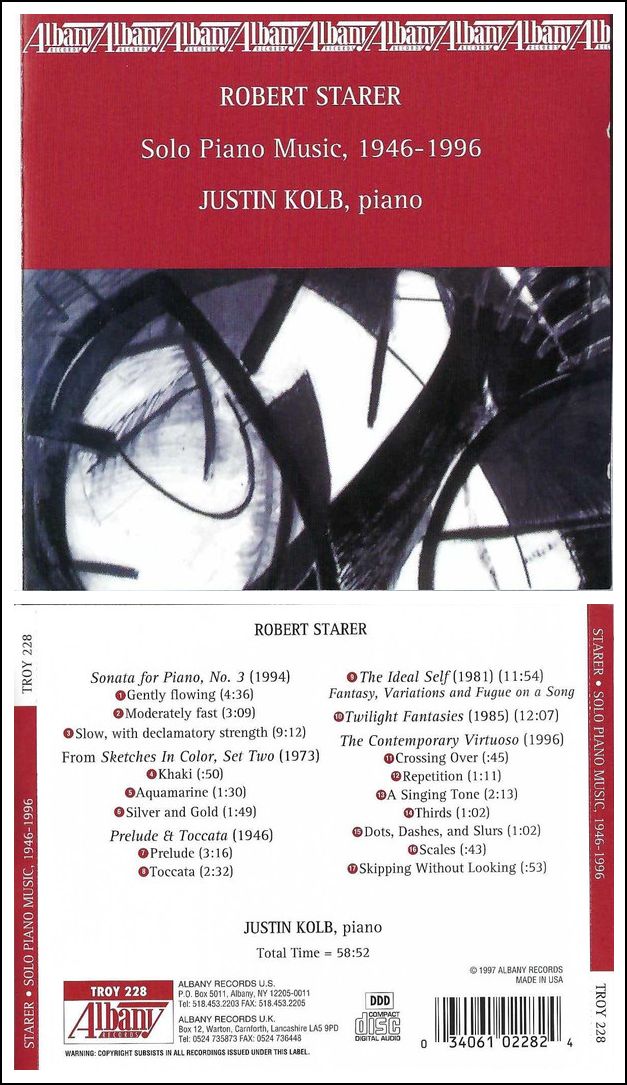

performances include premieres of compositions of Robert Starer, Paul Alan

Levi, and Jan Bach.

Kolb's program of Starer's solo piano music in Weill Recital Hall at Carnegie

Hall was hailed by The New York Times as, "A Piano Recital Program With A Difference." Kolb also

performs much of the standard keyboard literature with an emphasis on

Beethoven, Liszt, and Alkan. Kolb began his piano studies at age four and soon became a student

of Francis Clark and Lillian Whitaker DeCamp in Hammond, Indiana. He

made his concert debut at the age of ten in solo performances with the

Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the Gary Symphony. While serving as artistic director, Mr. Kolb

designed and developed The Belleayre Conservatory Summer Music Festival

in the Catskill Mountains, and serves as program advisor to several arts

organizations including the Woodstock Guild in Woodstock, New York and

The Center for the Performing Arts in Rhinebeck, New York. Kolb is frequently

engaged by colleges and universities to present his interactive lecture

titled KNOW THE SCORE: Inspiration and

Motivation for Surviving in the Business of Music. Also Travels with a Piano

Player and How

to Avoid Being a Nerd are two programs presented

by Kolb to grades K-12. These music enrichment and student motivation

programs are popular in the private and public school sectors. His musical

impact in all areas prompted DePaul University to present him with the

1994 Distinguished Alumni Award. At DePaul University, Kolb studied with Herman Shapiro, Alexander Tcherepnin, and Paul Stassevich. On loan from the US Army, Kolb was among the first to serve as a cultural ambassador under the US Dept of State and the United States Information Service. Performing concerts he also addressed student youth groups in Europe and the Middle East. He has studied with Rolf Beyer in Heidelberg, Gui Mombaerts in Chicago, Martin Canin and German Diez in NYC. Private lessons with Hans Rosbaud in the Chicago studio of Fritz Reiner are a special memory. Luiz de Moura Castro currently coaches Kolb. Kolb is currently on the Board of Directors of the American Liszt Society, is a co-founder of the Phoenicia Int’l Festival of the Voice and was recently named Chairman Emeritus. Kolb is married to prize-winning mosaic artist Barbara Mellon Kolb,

and they make their home in New York’s Catskill Mountains.

== Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

© 2002 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on May 18, 2002. Portions were broadcast on WNUR the following year, and again in 2006. This transcription was made at the beginning of 2026, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.