Mezzo - Soprano Carol Madalin

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Mezzo-soprano Carol Madalin may not be a well-known name, but she has performed

operas and concerts both in Europe and the U.S. Her most notable accomplishment

could very well be what brought us together. We discuss the circumstances

at the end of this interview, but suffice it to say that the recording she

had made of music of Respighi and Martucci gave her both notoriety and satisfaction.

We met at the end of June of 1994, and as we were setting up to record

our conversation, we spoke of recordings . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Since we’re talking about recordings,

let me ask how you happened to decide to record some music of Martucci

[CD shown below-left].

Carol Madalin: That was interesting.

I was auditioning for Glimmerglass Opera, and there was a young conductor

there named Alfredo Bonavera. He was at the audition, which went

well, and everything was fine. I was staying in New York because

it was one of those gimmicks where you had to stay over a Saturday night

to get the good airfare. [Both laugh] I got a phone call

from my manager who said that the conductor who was there wanted to hear

me for something else. I asked what kind of music, and she said

he wanted to hear art-songs. I didn’t have any music with me except

what I was bringing for the auditions, which was a role in one of the

operas for the season at Glimmerglass. So I was scurrying around.

I called up Patelson’s [the famous sheet music store across from

Carnegie Hall, which closed in 2009]. I also called a couple of

other friends, and asked if they could help me out, as I had nothing.

So I got some music from them. I just happened to be staying at

a friend’s apartment, and the audition took place in that apartment because

they had a studio with a piano. The conductor came over, and I

sang. I had my accompanist there, and at first, I wasn’t even sure

what this was all about. My manager said that he

was making a recording. [Laughs]

To say I was skeptical would be an understatement, but I auditioned

for him, and he seemed very pleased. He then wanted to hear some

more Italian, and he proceeded to tell me what the music was. It

was the Martucci songs, and Il Tramonto of Respighi. He

said he was making a recording in London, and, “They

have a singer for me, and I don’t like her. I heard you yesterday,

and I love your voice, and I want you to do this.”

I still just didn’t believe it...

BD: “I will make

you a star!”

Madalin: [Laughs] That’s right!

Then I asked him what the time frame was. This was early October,

and he said it was the first two weeks in November. I was just

looking at the score for the first time, and so the whole proposition

was a little overwhelming. Then there was the problem about working

in Great Britain. There’s a real fine line about it. You

have to be an international singer, and you have to have worked on

different continents. I didn’t know anything about this.

So, I went home, and got a call from my manager. She said, “He

wants to use you with the English Chamber Orchestra. They’re a

wonderful orchestra, and they make all sorts of recordings.”

We tried several different angles of how to get me over there, and finally

decided that I was to be paid indirectly through the man who was sponsoring

the recordings, and who was putting the money up front.

BD: Then you weren’t actually working over

there?

Madalin: No. I wasn’t really forthcoming

about it when I went through customs as to why I was there, because

I didn’t want to start all that, and have them say I couldn’t do this.

I simply said I was visiting.

BD: Customs is not the kind of thing

you think about when you’re vocalizing.

Madalin: No, and I really couldn’t be bothered

with all that. I had so much to do just to learn the music, because

it was new pieces. The Martucci is a long piece. It’s very

involved and somewhat dramatic, and then there was Il Tramonto.

There was no recording of the Martucci. I could listen to a recording

of Il Tramonto, and I don’t like to listen to someone else’s interpretation.

It’s fine after you’ve worked on the piece for a while, and you figure

out what it means, and how you want to do things. Then you can hear

somebody else and say whether you like that, or don’t like that.

But if you listen to someone else’s interpretation for the very first time,

it’s very hard not to have it color your perception of it.

BD: I’m glad you didn’t use that just to cram

it into your mind.

Madalin: Oh, no, no, and so I worked really

hard, and I took a week, and went to New York. Fortunately, the

pianist that I was working with had performed these songs before with another

singer, so he was very familiar with them. That was really a saving

grace. Just a week before I was ready to go over to London, I thought

this is never going to come together. There is so much more that

I could with this. I felt just a little overwhelmed, because to

learn something that quickly, and to put my stamp on it, really does take

time. It’s wonderful to learn a piece of music, and then put it

away for a while, because when you bring it out again, it just matures

all on its own without you even looking at it. I don’t know if it’s

a subconscious thing, but there’s always some added dimension that comes

back when you put it away for a while. But I really didn’t have the opportunity

to do this. I could only put it away for a couple of days.

BD: That was not enough time for it to steep.

Madalin: No, it’s not. [Both laugh]

BD: I assume it all did come together.

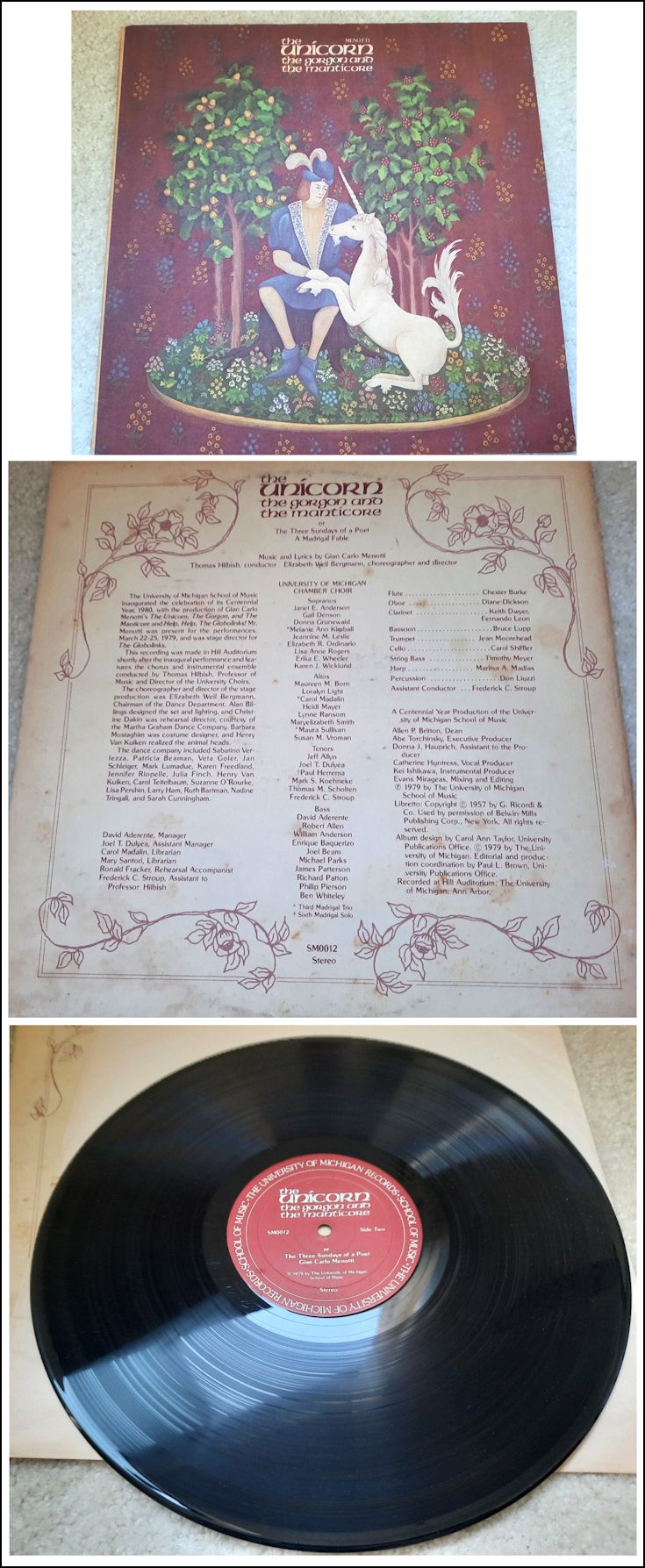

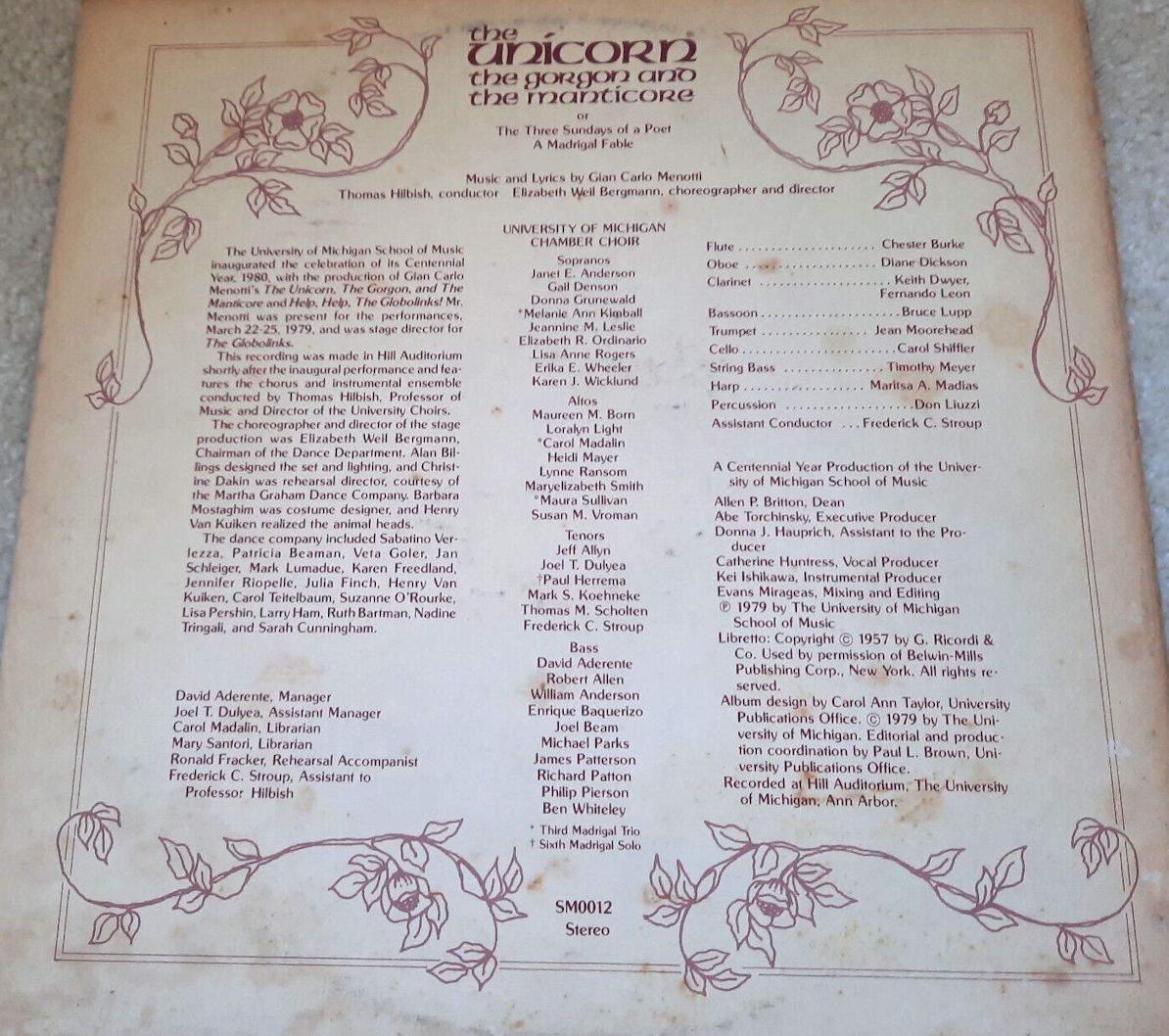

Madalin: It did. I was so naïve when

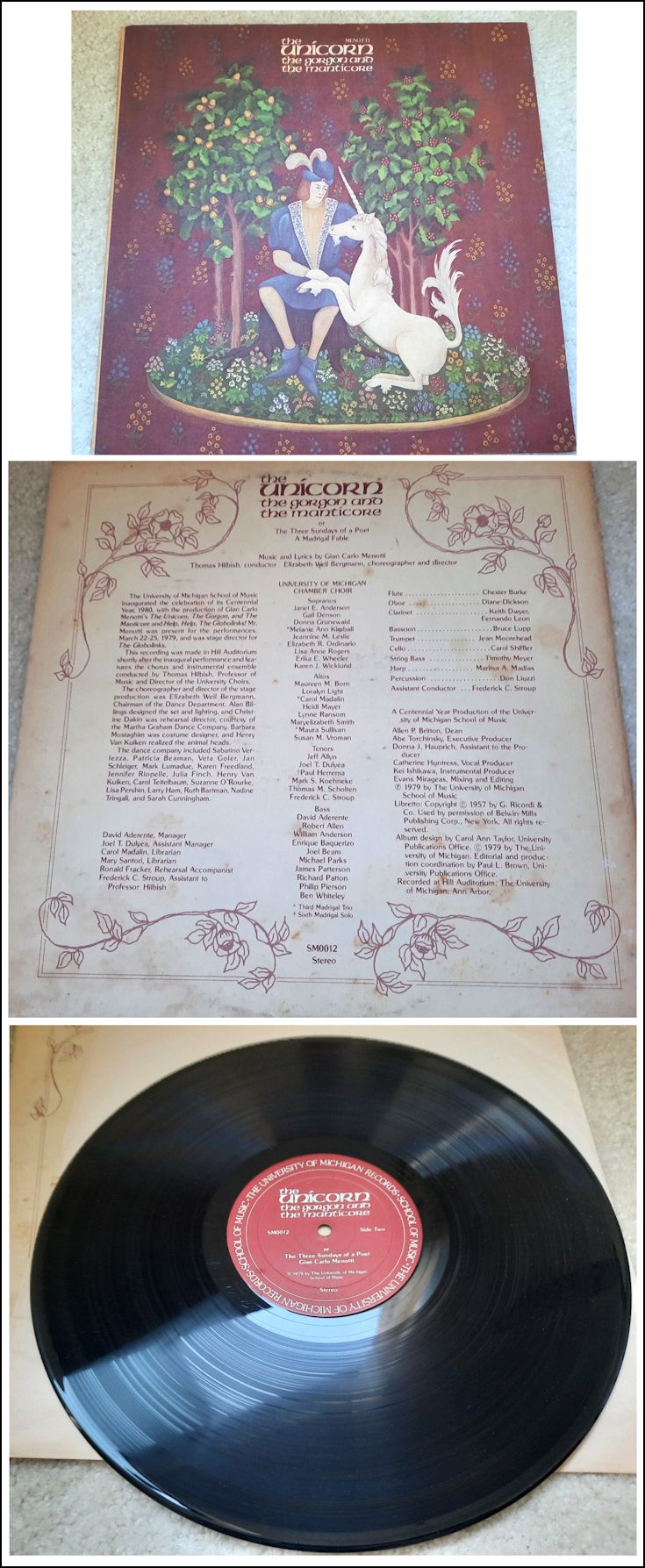

I went in there. The only recording that I had done was with my

college. We recorded The Unicorn, the Gorgon, and the Manticore

of Menotti [LP

shown below-right]. I had done one part of the trio, but I

just remember we were all standing around and trying to be quiet a lot.

I had no clue as to the whole process. When I got to London,

there was this professional well-put-together orchestra, and all they

knew is that this conductor was coming in, and he was bringing his American

singer with him. I found out later that they were all ready just

to put me on a chopping block. Then I opened my mouth to sing, and

they changed their minds immediately! They said, “Where

did you find her?” So, I was happy about

that.

BD: You were a true discovery.

Madalin: I’m glad I didn’t know that beforehand.

There were some things I was naïve about, because it would have

all frazzled me a bit.

BD: It’s nice to know that you got up there,

and proved yourself immediately.

Madalin: Yes. I don’t know if you’ve

been in London in November, but it was very damp. We recorded

this in an old stone chapel, not in a studio. There was no little

booth that I stood in with headphones. We were all doing it together

and we had two days to do it all. He spent much of the first day on

the Martucci piece that is just the solo orchestra. That’s the thing

he wanted to start with, and I was just standing in the back, pacing, and

wondering if I was ever going to get to do my part. I knew we just

didn’t have that much time, so finally when I got to sing, it was such

a relief. We rehearsed each piece before we recorded it, and they

wanted to hear me, so I would turn around to the orchestra, and sing to them.

Then we would work out a few things, and I would turn back to the front

when we did the recording. Had I been a seasoned person who does

lots of recordings, I would have realized that this was very taxing vocally.

BD: You shouldn’t sing full-out in rehearsals,

and then sing full-out for the recording.

Madalin: Right, exactly. The second

day I realized that, because I could feel that my voice was getting

tired! In opera rehearsals, unless it’s a dress rehearsal they

never expect you to sing full-out.

BD: Sure. You have to ‘mark’.

Madalin: That’s right. I was so excited

about singing it, and it was so exciting. It was wonderful to finally

hear it with the orchestra, because the orchestration is really special,

especially in the Martucci. I just wanted to sing, and had I been

a little smarter, I would have saved my voice just a bit. The recording

engineer, whose name was Martin Compton, was just a special person. He

was very sensitive, and was really concerned about my welfare. So

he would come up to me in private and he’d say, “Now Carol,

I think you can do that a little better this time, because this

note wasn’t quite the same tone.”

BD: He was being helpful?

Madalin: He was wonderful, because the conductor,

Alfredo Bonavera, had so much going on. He was so concerned and

so involved with the orchestra, and I felt like Martin was really on

my side. He was listening to me, and making sure that I was at

my best, even though he didn’t know me. We had just met. During

the breaks he’d ask me if I wanted to hear some of what we had just recorded.

It was such a wonderful experience because of him. Before we

left London, he gave me the copy of the recording. It wasn’t the

master. It wasn’t the finished product, but it was what he thought

was the best material. My mother was with me, and he had us over

to listen to the recording. We had tea, and it just so happened that

it was my birthday. It couldn’t have been a nicer birthday present

to hear what we had done just a few days before.

BD: Are you pleased with the end-product that

has been issued?

Madalin: Yes, I am. We did a lot of

takes at the beginning of Il Tramonto, and there was one where

I had a frog in my throat. I had to clear my throat, but I kept

singing. This is one thing I also learned. If you have a

problem, or if you make a mistake, you have to stop, because if you don’t,

and you keep going, the tape keeps going and they can use that. In

the Respighi, anytime one of the strings made a mistake, the whole process

stopped. They made sure that it did, [Both laugh] You

learn a lot from previous experience.

BD: I trust they didn’t use that take with

the frog in your throat...

Madalin: When Martin and I were listening

to it, I said, “Oh, no!”

He asked what it was, and that was the take when I had the frog in my

throat. He said “Yes, but even though you

have that, the mood that you’re creating was so special that I really

wanted to use it.” I decided to leave it

up to their judgment if they think if it’s more magical. The beginning

of that piece is very exposed, and it really sets up the whole story

for the piece. I will just get over the fact that there’s one note

I have a frog in my throat. It was really just one note, and it

was just for a short time on that note. But being a singer, I could

hear it. [Laughs]

BD: You knew it was there, so you’re anticipating

it. But no one else will know it.

Madalin: No, and when the recording came out,

there was no frog! [Has a huge laugh]

BD: There you are!

Madalin: It was very interesting that it was

coming out on cassette and compact disc, because that was about the

time that Hyperion was totally phasing out vinyl records. I was

really surprised. I was talking to one of the mangers of Hyperion,

and he was very pleased with the whole recording. He said that he

could see within a year or two that it will all be CDs...

BD: ...and he was right! [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown at right, a larger size image of the back cover can

be seen at the bottom of this webpage. Note that Madalin is also a

librarian for the group!]

Madalin: He was so right. My father

bought the CD, and then he had to go out and buy the CD player!

BD: Was that manager Ted Perry?

Madalin: Yes.

BD: He blew through town several years ago,

and I did an interview with him marking twenty years of Hyperion recordings.

He was a very nice fellow.

Madalin: Yes, very nice. We had a Guinness

stout in a pub together.

BD: So, the dangerous question... Why

haven’t they asked you to make more records?

Madalin: I would love to go back and work with

them. The English Chamber Orchestra called me a year later, and wanted

me to come and perform. They wanted me to do some Haydn, and things

were in the works to start that ball rolling. I was so excited. They

said it was going to be in the Royal Festival Hall, but unfortunately

what happened was the whole status of working and being intercontinental.

I was still just a North American performer. That’s how they

label it. There are all sorts of stipulations, and that’s what held

it up because it just didn’t materialize. I was really disappointed.

Ted Perry liked me very much, and there was a man who was Swiss who

was financing this recording, because he was friends with the conductor.

Bonavera had said this music must be recorded. It’s very important,

and this is what he wanted to do. Making recordings is a tricky thing.

I really admire the Hyperion label because they do have some unique

pieces, and they don’t really seem to care necessarily about keeping it

mainstream. As for my own career right now, I need to make those

contacts again, because I did it all through Ted Perry. He brought

me into it, but when you make a contact like that, you have to pursue it.

He liked me, and he wanted me to do other things. He was very

proud of how the whole thing came out, and he was also pleased with the professional

way I handled myself during the recording. The first day we never

had to stop because of a mistake that I made. It was always someone

else. The second day, on the very first take I said a wrong word,

so we had to stop. Then for about ten minutes I was nervous. On

the first day there wasn’t a nerve in my body. It was such a wonderful

experience to do this recording, and to hear this music. Then, on

the second day it kind of caught up with me. Then I pulled it back

together, and all was fine.

BD: Now that you’ve made this recording, have

you tried to get other live performances of these pieces?

Madalin: I tried that when I came back, especially

on a local level. I was really trying to get some of these symphony

orchestras that are in the area. I met a conductor of one of

the Chicago area symphony orchestras, and I told him that there are these

great pieces, and I had recorded them, and he really had to listen to

them. But it’s a matter of familiarity. People have never heard

of this music. They don’t know the history, and they’re not really

sure what it’s all about. Also, it can be a problem getting a singer

to be the soloist. The whole piece is one-singer-with-orchestra,

and that overwhelms a few conductors as far as programming, and putting

it in their series.

BD: Has this encouraged you to do more art-songs,

as opposed to opera?

Madalin: Oh, absolutely. I always felt there

were some connections with the art-song, because, as a lyric mezzo,

the roles that I have in opera are not always the most exciting.

Rosina is definitely something that’s wonderful, and I would perform

that wherever. But a lot of the stuff I was singing, and that I

was being considered for, was just not that satisfying. It was

fun, and I enjoyed Stéphano in Gounod’s Romeo and Juliet,

especially doing my sword fight. I had a good time, but musically

it’s not that challenging. There’s not a

lot of levels to being a page, or even portraying Dorabella [in Così

fan Tutte]. As much as I love her, she doesn’t have a whole lot

of depth to her soul. With art-song I did the Schumann Frauenliebe

und Leben for the women’s group that I’m involved with, the Musicians

Club of Women. [Musicians Club of Women is dedicated to creating

a vibrant classical music community in Chicago. Founded in 1875, MCW

is one of the oldest musical organizations in Chicago, continuously supporting

emerging and established women musicians through scholarships and performance

opportunities.] I specifically wanted to do that for

the ladies (as I call them), because it’s a wonderful piece. The whole

cycle goes through the life of an adult woman, from the time she sees this

man, to him talking to her, to her realizing that this man has chosen her,

to their wedding, to the fact that she has a child with him. Then

it takes a big step when he finally is no longer in her life because he has

died, and she’s all alone. There’s something really special about

singing a whole cycle like this Schumann, or the Martucci, because you

have the start, the middle, and the finish. It’s a complete work,

and it flows. Each song is in a key which is related to the others,

and it’s so wonderful to be able to do the whole thing. That’s why

I wanted to do it. I didn’t do that for the performance in the public

library. I really wasn’t sure that their Cultural Center was ready

for that particular piece. [To see photos of the Chicago Cultural

Center in the former Chicago Public Library, click HERE.]

It’s different if you perform a whole recital, just yourself, and

you can program that piece.

BD: This was half a recital?

Madalin: Right, right.

BD: I hope you get asked back so you can do

more of these things.

Madalin: Yes. With regards to the Cultural

Center, they usually split it up between two or three performers. The

Dame Myra Hess concerts usually have two different artists, and the

Award Winners in Concert is also two different artists. But it’s

a rare opportunity to be able to perform art-songs. The genre

is so huge, and there are so many wonderful composers, and even more contemporary

composers.

BD: With the vast array of items to choose

from, how do you select them, and form a program?

Madalin: [Laughs] That’s a good question!

I have so much music at home, and I literally just flip through it and

see what I love. I have just started working on the Elgar Sea

Pictures. I did two of those at the library, and I would

love the opportunity to do that whole cycle. I just think it’s

wonderful. One time when I was on the road, I heard Marilyn Horne perform those,

and I thought these are really wonderful songs! So, I would like

to do the complete set, and also Les Nuits d’Été

of Berlioz. The first person I heard was sing that was Janet Baker.

Except for some American music, I’ll hear recordings and something

will speak to me. I’ll hear a song and I’ll think that I really want

to hear the rest of it. Or I’ll wonder if

there’s more to it than just the one song. In college, we always

tried to explore. If it was a song cycle, we always tried to explore

the poet and the whole cycle.

* * *

* *

BD: Now you’ve taken a couple of years off, and

had a family and a couple of children. Is it good now to be getting

back into this whole routine, and maybe going back out on the road?

Madalin: [Laughs] Just this past Monday,

I said to my accompanist that when we finally get to the Cultural Center,

then it’s going to be easy, because it’s a madhouse before that.

My three-year-old can just tell when Mommy is about to perform, because

the tension level gets high, and she feels it, even though she can’t

quite comprehend what it’s all about. But it’s a good time now

to get my career going again, since I’ve had the family and the children...

BD: [With mock horror] But you can’t

just put them aside!

Madalin: [Laughs] No, but my plan of action

here is not necessarily opera, because usually opera is a big time commitment.

But I really want to explore the concert avenue, because there are

times where you go in to the city in which you’re performing, you have

two rehearsals, usually one rehearsal with the conductor and just the

singers, then one with the orchestra. It depends on the organization,

but then there is the performance. So it’s generally a four-day commitment.

You have to know your music when you come, and it is all very satisfying.

I did the Beethoven Missa Solemnis when I was pregnant with my

first child, and it was just a wonderful experience. It is wonderful

music, especially to perform it with the orchestra and chorus. So

I’m really looking at that avenue to get myself back in. In this

country, it’s very hard to be a concert singer, so I’m going to have to

find people to ask what’s the best way to pursue this. There have

been people who do this. Janet Baker is one. She did a lot

of concert work, and she got into opera a little bit later. Also,

Jessye Norman and Kathleen Ferrier did a lot of concert work, oratorio,

and recitals. Then when people’s ears perked up, they said they’d

love to hear that singer in an opera!

BD: So, you’ll have roles like Orfeo

and a few other things ready, but do the art-songs first?

Madalin: Yes. There is wonderful concert

repertoire, with lots of Mozart concert arias, and Haydn, and other items.

These are things which need be explored.

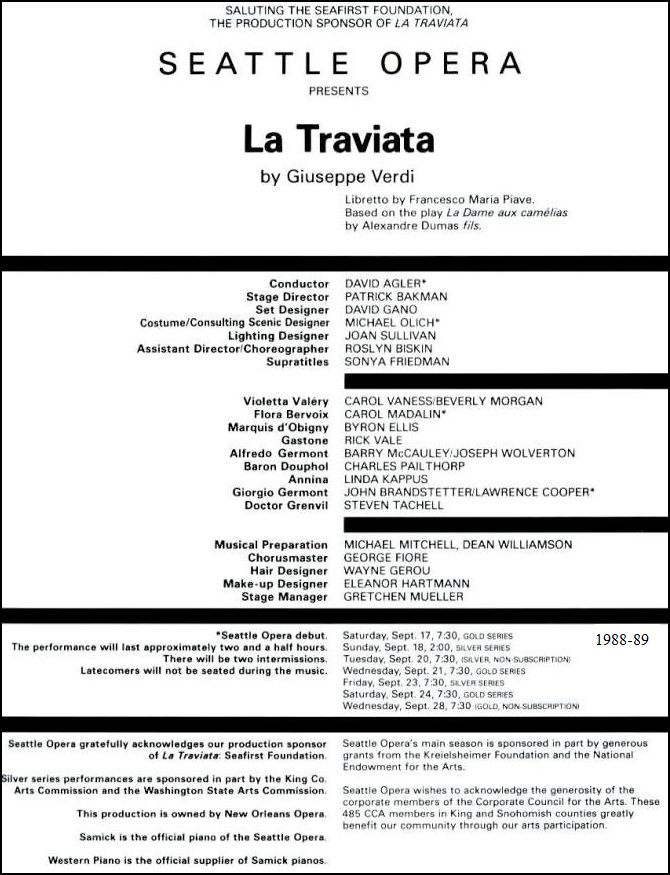

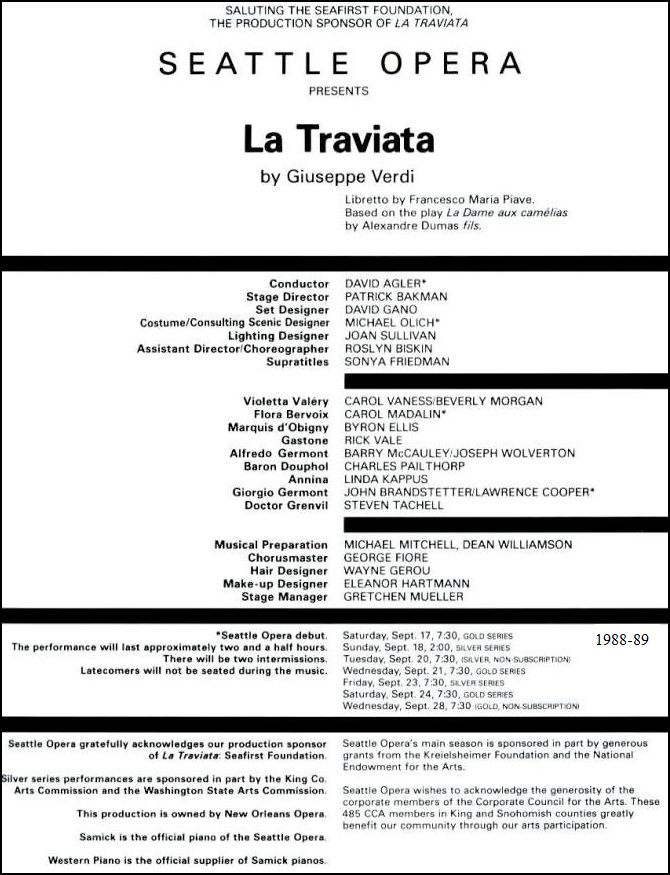

BD: No matter what the work, is singing fun? [Vis-à-vis

the program shown at left, see my interviews with Patrick Bakman, Carol Vaness, and Barry McCauley.]

Madalin: Oh, it’s great fun. [Laughs]

Yesterday I was telling somebody about this. You stand up there

and pour your heart out. The first time I sang at the Cultural Center,

there were people who were asleep. You think that people are just

not paying attention. They’re not listening. They don’t care.

Then there’s that one person who comes up to you afterwards and says

that you touched their soul when you sang! It’s just such a great

feeling. It’s hard to describe. I just

want to thank that person for understanding what I’m trying to do here,

and what this is all about. That’s happened a number of times. It’s

funny, because sometimes it happens when I feel like it was really awful!

Then someone comes up and says that it was just so special! Sometimes

people are so overwhelmed. Maybe it’s the quality of my voice, or

something that they hear or feel that I’m expressing or sharing. It’s

almost embarrassing. It’s like they know something

about me, and I can’t figure out how they know.

BD: In a way, when you’re standing up there

singing, you’re baring your soul for them.

Madalin: Yes, definitely. There’s some music

that just speaks so strongly. The Verdi Requiem is just such

a piece. Every time I sing that, there’s something else to be discovered.

Even though Verdi was a professed atheist, there is still something

that comes through in that music, and it speaks to millions of people.

It didn’t matter what he believed, or what he felt personally, and

that’s exciting. That’s the thing which makes it all worthwhile.

It’s not always whether the critic is going to like me. A

lot of people lose sight of that. I know a lot of really successful

singers that become jaded because they lose sight of what it’s really

all about, and that’s just music. Music can cross any barriers.

Music can speak to people in any language. It doesn’t matter if

you even have the same beliefs, or even if you’re on the same side.

It’s just not important. Music can, as they say ‘soothe a savage

beast!’ [William

Congreve (1670-1729) is famous for the line ‘Music

hath charms to soothe a savage breast’, which he wrote in his 1697 play,

The Mourning Bride.

While

often misquoted as ‘Music hath charms to soothe a savage

beast’, the original quote refers to the

power of music to calm a wild or angry heart.]

But it can provide much more, and I just feel it’s so important

to have that in our lives. I want my children to appreciate all music,

not just the music that I like. They should find something worthwhile

in all music and the arts, because it removes us from our little selves

so that we see the bigger picture. That’s what it really is for me,

and sometimes it’s just so much fun. On Monday, the last piece I sang

was Una voce poco fa [Barber of Seville], and I thought I

should just do it and have fun with it. I knew that the audience could

tell. They can see that. It’s so wonderful to be able to stand

up there and feel that confidence in my ability to make it fun for them,

and to show them that even though they might not like classical music, this

is fun, even though they don’t know what I’m singing about because it’s in

Italian. One of my neighbors who works downtown came up afterwards.

She’s not an opera fan, but she said she really believes that opera

should be sung in the original language, because even though she didn’t

know what I was singing about, she had so much fun! She could just

tell from the gestures and the inflections in the voice what it was all

about.

BD: I’m glad you are the possessor of a voice than

people enjoy hearing, and also have the intelligence to do something

with that voice. It’s quite a combination.

Madalin: Yes, it is. The instrument is just

unbelievable, and yet as far as doing something with music or saying

something with music, that’s really it, because that’s not something

people can teach you. Coaches say to do this or do that, or sing

it this way, but it’s just like the great actors of our time. If

they don’t put something of themselves into it, then there’s really not

much that gets communicated. You have to be willing to put yourself

out there, and there is a great deal of vulnerability. Sometimes it’s

a little scary, but...

BD: Thank you for being willing.

Madalin: You’re welcome!

BD: It’s been nice to chat with you. I’ve

admired this recording for a long time...

Madalin: Oh, thank you.

BD: ...and I had no idea that you were living

amongst us! You’re going to remain with the Chicago area as your

base?

Madalin: Yes. It’s a really great place to

be, and there are a lot of opportunities here. I have yet to partake

of some of them, but I’d like to, and it’s a good jumping off point. There’s

a lot of work in the Midwest, and it’s easy to get to both coasts. Plus,

it’s a wonderful place to raise a family.

BD: Yes. Never lose sight of that.

Madalin: Right, absolutely. They won’t

let me! [Much laughter] My second daughter is enchanted with

singing. She just loves it. She just goes, “Ooo,”

and, “Ahhh,” so she’ll be

the easier one to get to accept my career.

BD: Your hubby is supportive of all this?

Madalin: Oh, absolutely! Sometimes he’s

actually a little anxious for me to get back and do it. He’s probably

my biggest fan, and my best critic, because he really believes in me.

That makes a big difference.

BD: What’s next on the calendar?

Madalin: I’m doing a Messiah in Corpus Christi,

Texas, but that’s not until the fall. Last fall, when all the auditions

were taking place, I was having a baby, so I’m going to miss a whole season.

People don’t know that I have to get my name out again now, and let

them know I’m back on the circuit. Then in the fall I have to

make some trips to New York, and also do some auditions just to let people

know that I’m available again.

BD: I hope it all works out well for you.

Madalin: Yes, thank you!

BD: It’s so funny the way this came about...

I was playing your recording, and had jotted a note to get your contact

info, so that I might be able to catch you when you came to town. The

note was sitting on my desk, and all of a sudden I get a call from you!

Madalin: It was just pure chance that I happened

to hear it. Initially I heard the music, and wasn’t sure... I

thought it sounded familiar, and then like a flash I realized it was me!

[Both have a huge laugh] So, it was quite a pleasant surprise

to hear it, and then to be able to have a follow up. I certainly

appreciate you putting that in your program.

BD: When you were doing Stéphano [Romeo and

Juliet of Gounod with Chicago Opera Theater

in 1989, featuring Gregory

Kunde (who had also been a member of the Lyric Opera Center), conducted

by Mark Flint, and staged

by Dominic Missimi],

I wanted to set up an interview, but for some reason, it just didn’t work

out. I remember seeing the performance, which I enjoyed very much,

and then I figured you would be off to another engagement.

Madalin: Yes. Earlier I was with

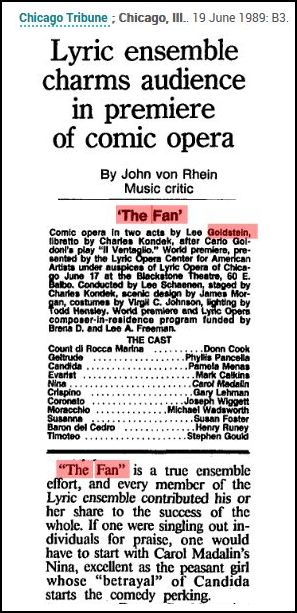

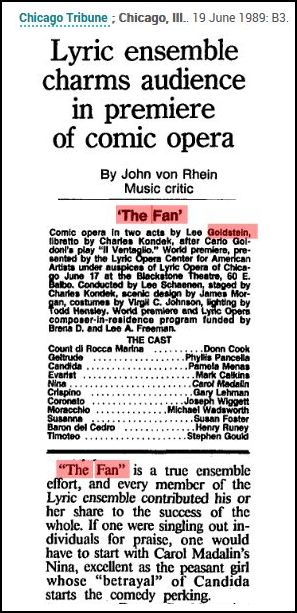

the Lyric Opera Center, and after that they did the world premiere of Lee Goldstein’s

opera The Fan [part of a review is shown at right]. They

needed a lyric mezzo, and they wanted to use me because I was a former

student.

BD: How long had you been in the Lyric Center?

Madalin: I was there for two years, 1981 and

1982. That’s when I first came to Chicago. Then I was gone for

the next three years. I auditioned for Carol Fox [General Director

of Lyric Opera], but by the time I got to Chicago to start the program,

she was gone. My first year was also the first year for Ardis Krainik [who

succeeded Fox].

BD: Where are you from originally?

Madalin: From Michigan, from the Detroit area.

So, I am a Midwest girl. After I had been in Chicago, they

wanted me to come back for The Fan, and it was a wonderful experience

doing that.

BD: I enjoyed that opera very much.

Madalin: It was fun.

BD: It was a great shock when Goldstein died.

Madalin: I was devastated. I was in

Washington covering a role of Tina in The Aspern Papers [by Dominick Argento. The

role was created by Frederica

von Stade, and the 1987 premiere was telecast on PBS. Also in the

cast were Elisabeth

Söderström, Neil Rosenshein, Richard Stilwell, and

Eric Halfvarson.]

Argento was a friend of Lee’s teacher. Lee and I were kind of buddies.

I used to see him on the street occasionally (on Broadway!), and we would

talk. He said he had sent a manuscript, a score, to Lake George, and

they were thinking about it! It was all very exciting for him.

I told him that if he wanted to a make a recording, I’d be happy to do my

role again. When I heard he had passed away, it was such a shock because

he had such talent and wit.

BD: I’m glad that you’re doing some music by living

composers.

Madalin: It’s fun. I did Argento’s Postcard

from Morocco, which is a real challenge, but what a piece! When

I was understudying the role of Tina, that music just really touched me.

There’s just something special about his music and particularly that piece.

BD: Thanks for coming in tonight.

I appreciate it very much.

Madalin: You’re welcome. Thank you for

having me.

© 1994 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on June 30, 1994.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following November.

This transcription was made

in 2025, and posted on this website

at that time. My

thanks to British soprano Una Barry for

her help in preparing this website

presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this

website, click here.

To read my thoughts

on editing these interviews for print,

as well as a few other interesting observations,

click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster

Bruce Duffie was with WNIB,

Classical 97 in

Chicago from 1975 until

its final moment as a classical

station in February of 2001.

His interviews have also appeared

in various magazines and journals since

1980, and he continued his broadcast series

on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited

to visit his website

for more information

about his work, including

selected transcripts of other

interviews, plus a full list of

his guests. He would also like to

call your attention to the photos

and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the

automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send

him E-Mail with

comments,

questions and suggestions.