|

Described by the New York Times as “one of America’s finest artists and singers,” Frederica von Stade continues to be extolled as one of the music world’s most beloved figures. Known to family, friends, and fans by her nickname “Flicka,” the mezzo-soprano has enriched the world of classical music for four and a half decades.

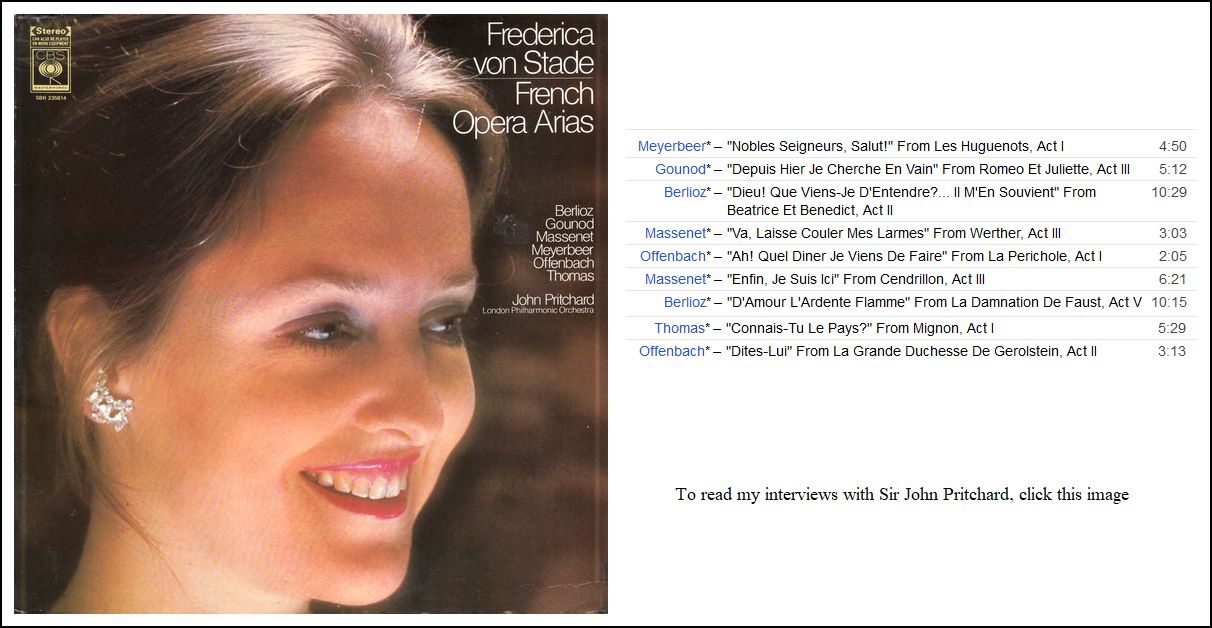

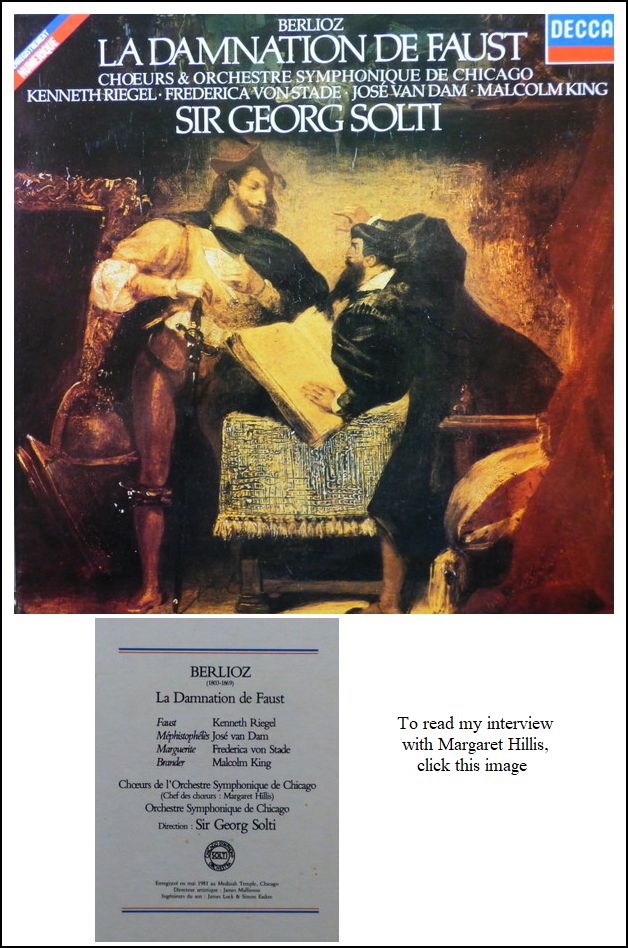

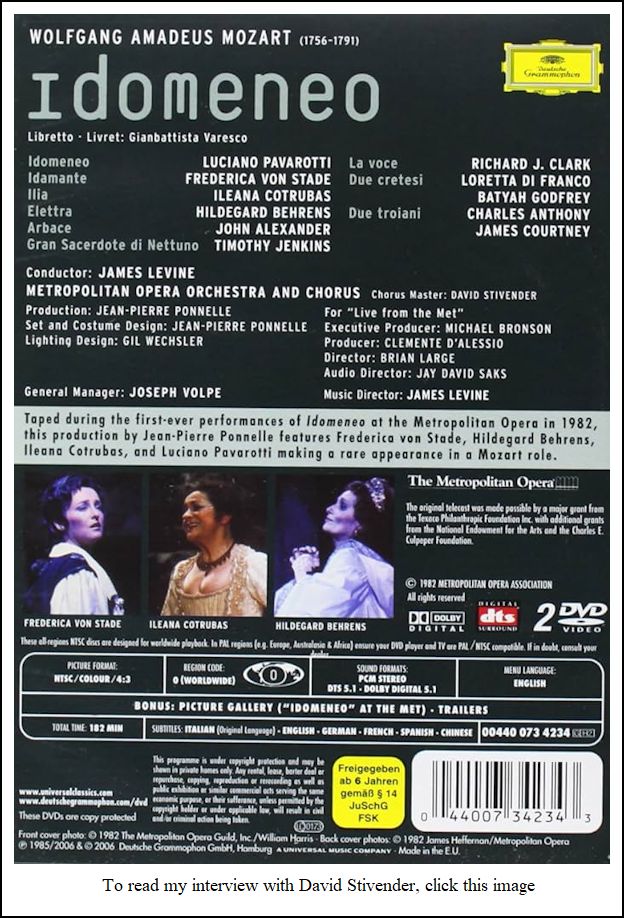

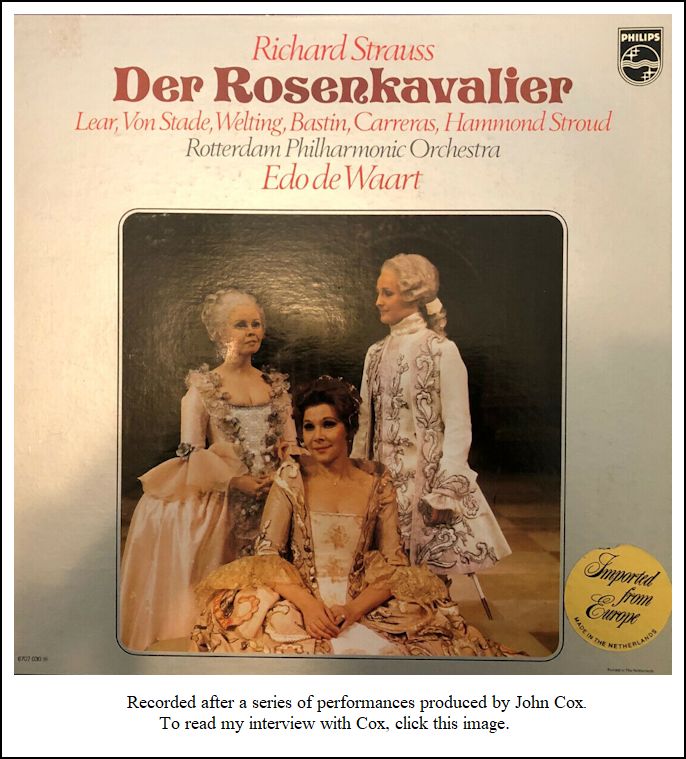

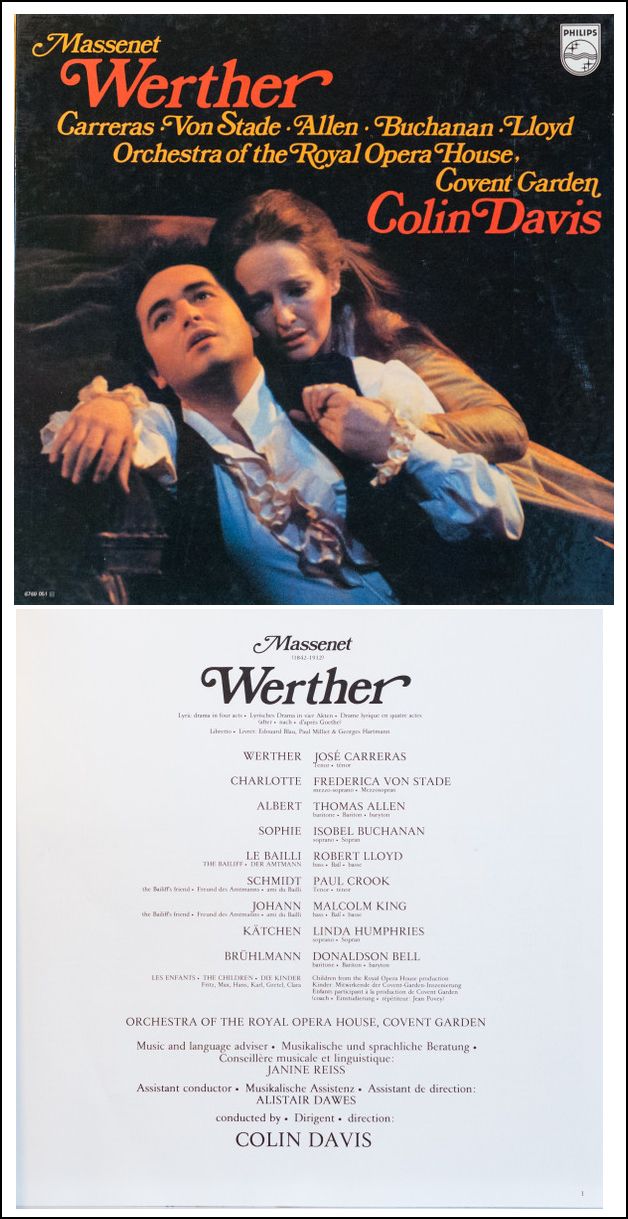

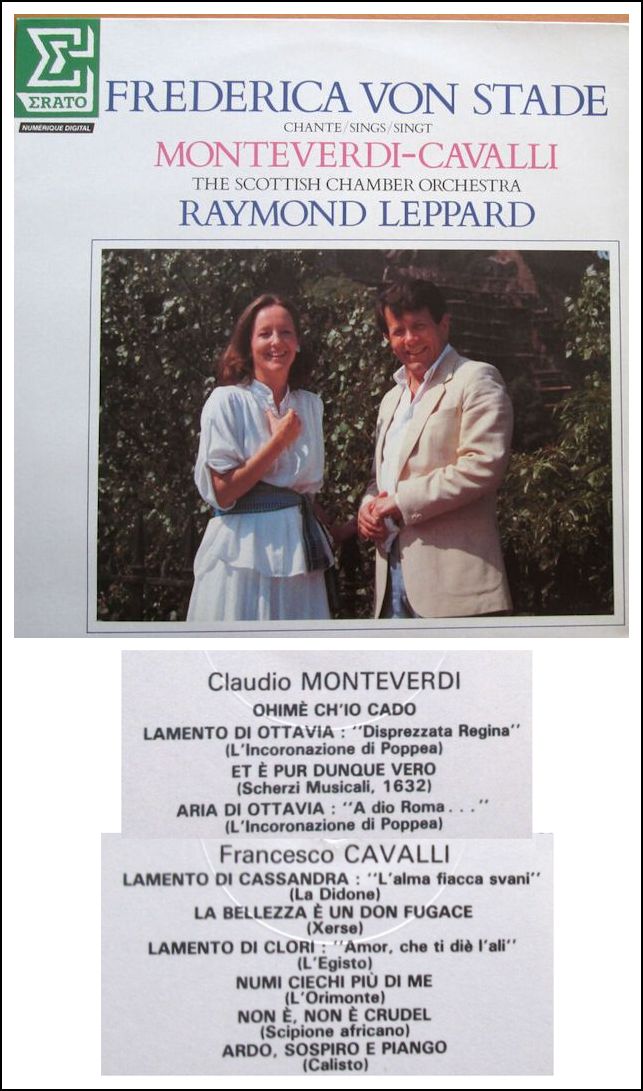

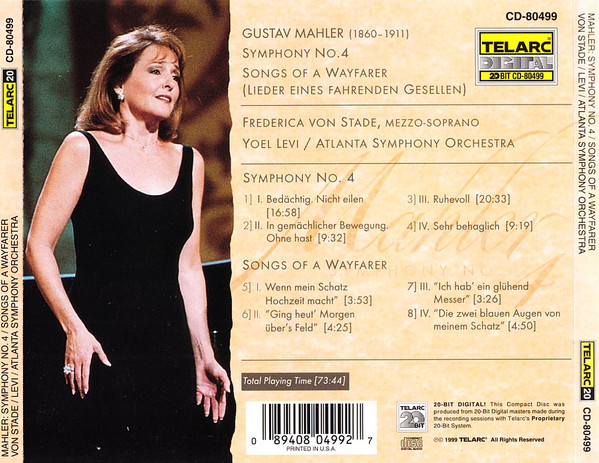

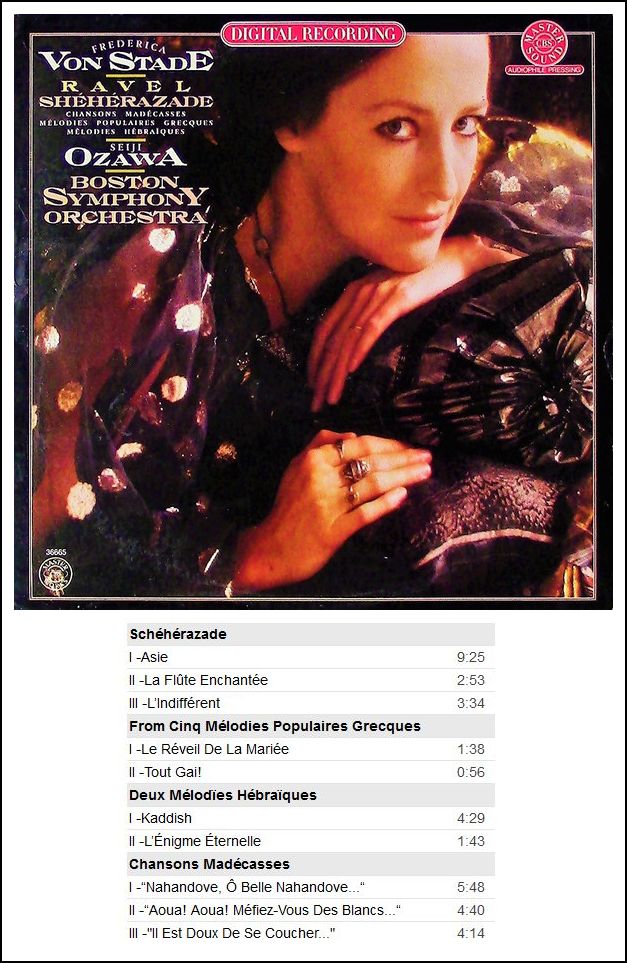

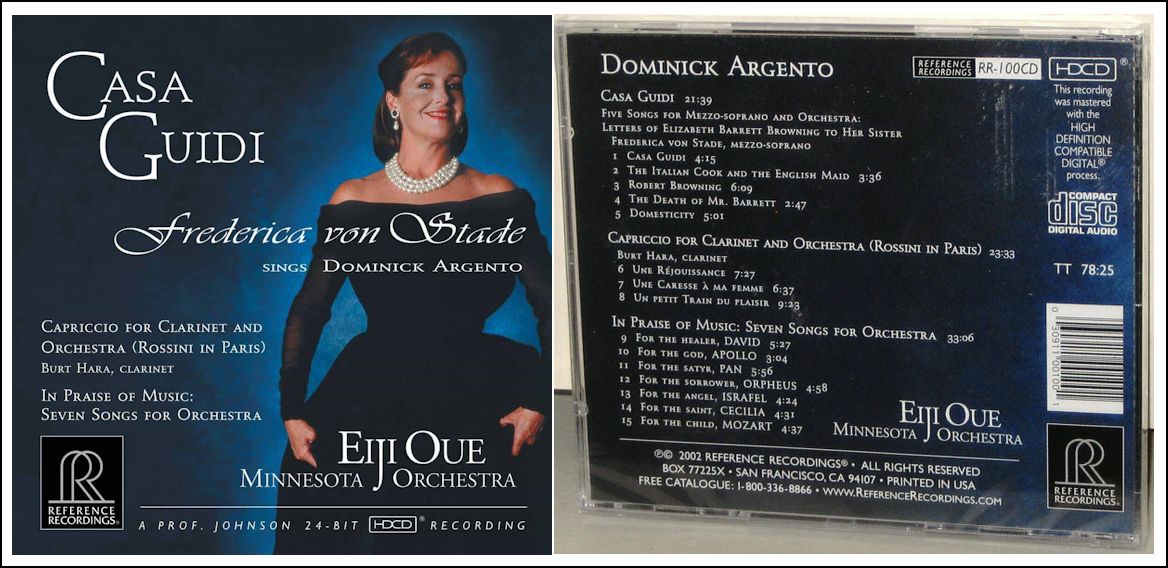

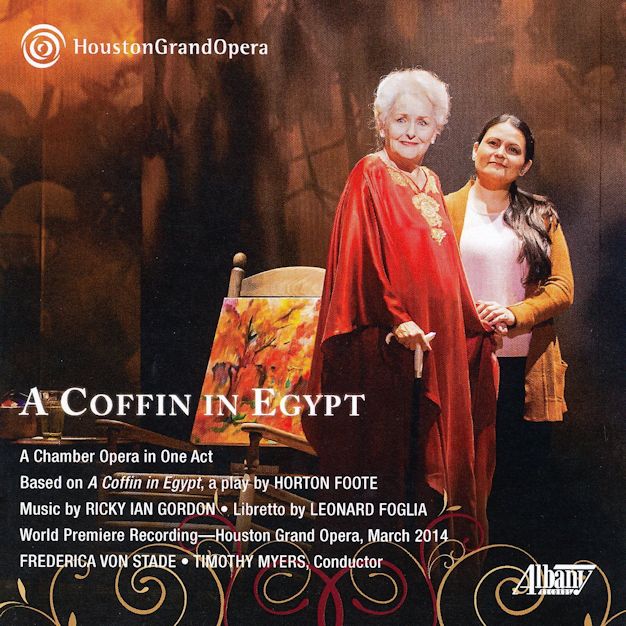

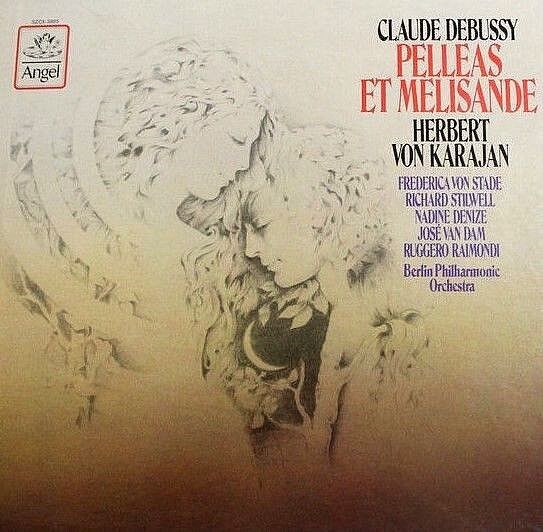

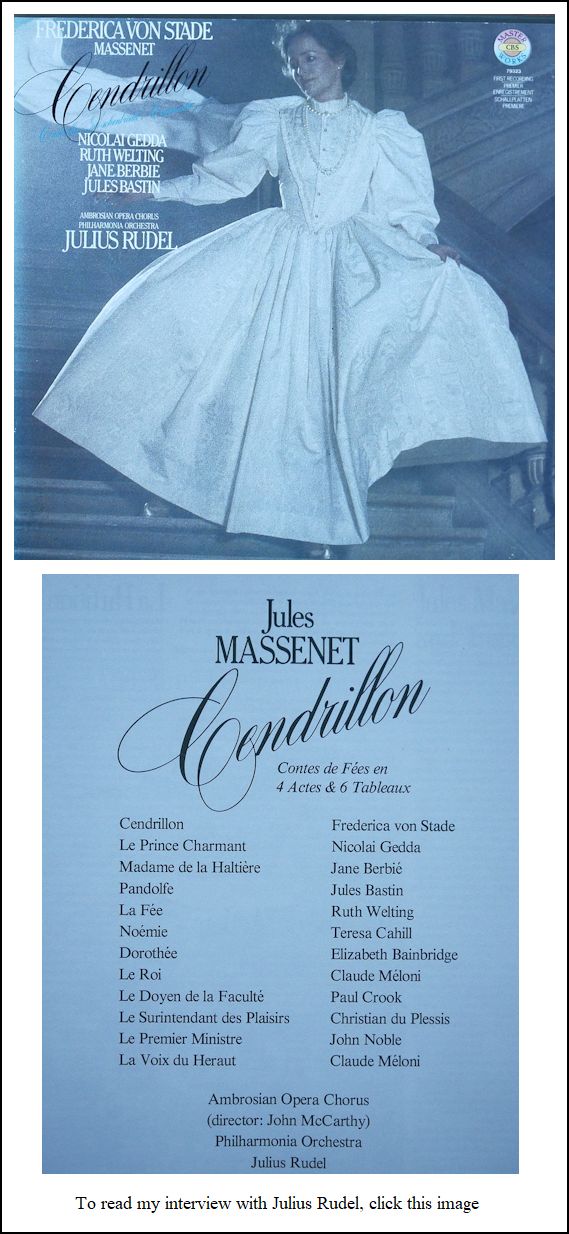

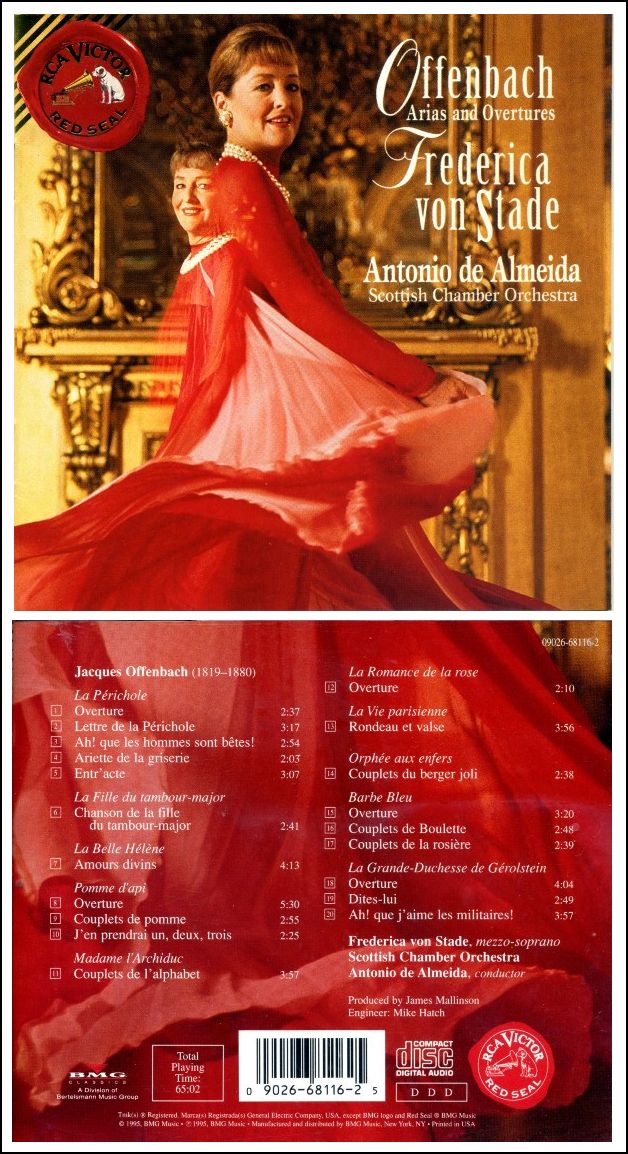

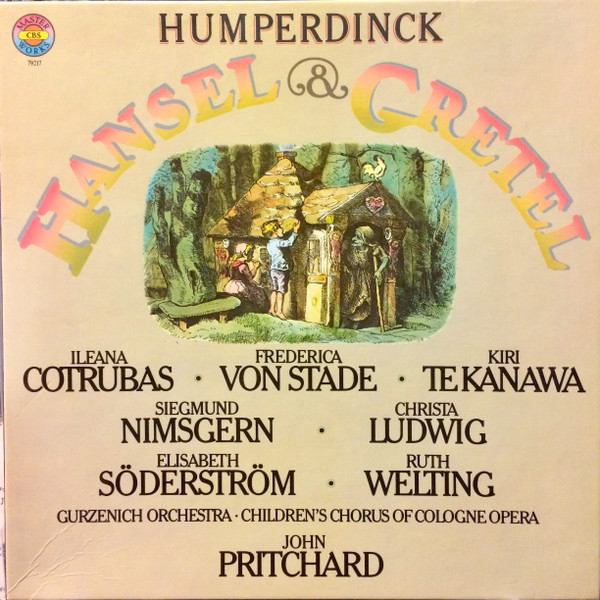

Ms. von Stade’s career has taken her to the stages of the world’s great opera houses and concert halls. She began at the top, when she received a contract from Sir Rudolf Bing during the Metropolitan Opera auditions, and since her debut in 1970 she has sung nearly all of her great roles with that company. In January 2000, the company celebrated the 30th anniversary of her debut with a new production of The Merry Widow specifically for her, and in 1995, as a celebration of her 25th anniversary, the Metropolitan Opera created for her a new production of Pelléas et Mélisande. In addition, Ms. von Stade has appeared with every leading American opera company, including San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and Los Angeles Opera. Her career in Europe has been no less spectacular, with new productions mounted for her at Teatro alla Scala, Royal Opera Covent Garden, the Vienna State Opera, and the Paris Opera. She is invited regularly by the finest conductors, among them Claudio Abbado, Charles Dutoit, James Levine, Kurt Masur, Riccardo Muti, Seiji Ozawa, André Previn, Leonard Slatkin, and Michael Tilson Thomas, to appear in concert with the world’s leading orchestras, including the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, London Symphony Orchestra, Washington’s National Symphony, and the Orchestra of La Scala. With impressive versatility, Ms. von Stade has effortlessly traversed an ever-broadening spectrum of musical styles and dramatic characterizations. A noted bel canto specialist, she excelled as the heroines of Rossini’s La cenerentola and Il barbiere di Siviglia and Bellini’s La sonnambula. She is an unmatched stylist in the French repertoire: a delectable Mignon or Périchole, a regal Marguerite in Berlioz’ La damnation de Faust, and, in one critic’s words, “the Mélisande of one’s dreams.” Her elegant figure and keen imagination have made her the world’s favorite interpreter of the great trouser roles, from Strauss’ Octavian to Mozart’s Sesto, Idamante and – magically, indelibly – Cherubino. Ms. von Stade’s artistry has inspired the revival of neglected works such as Massenet’s Cherubin, Thomas’ Mignon, Rameau’s Dardanus, and Monteverdi’s Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria. Her ability as a singing actress has allowed her to portray wonderful works in operetta and musical theater including the title role in The Merry Widow and Desirée Armfeldt in A Little Night Music. Ms. von Stade enjoys close collaborations with several contemporary composers, including Jake Heggie, Ricky Ian Gordon, and Dominick Argento, among others. She created the role of Tina in The Dallas Opera’s world premiere production of Argento’s The Aspern Papers (a work written for her), as well as the role of Madame de Merteuil in Conrad Susa’s Dangerous Liaisons, and Mrs. Patrick De Rocher in Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking, both for San Francisco Opera. Ms. von Stade created the role of Myrtle Bledsoe in the world premiere of Ricky Ian Gordon’s A Coffin in Egypt at Houston Grand Opera [DVD shown farther down on this webpage], a role she later reprised at Opera Philadelphia, The Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills, and with the Chicago Opera Theater. Ms. von Stade will also create the role of Mrs. Edward “Winnie” Flato in the world premiere of Jake Heggie and Terrence McNally’s Great Scott directed by Jack O’Brien, with performances at The Dallas Opera and San Diego Opera. Ms. von Stade’s orchestral repertoire is equally broad, embracing works from the Baroque to those of today’s composers. She has garnered critical and popular acclaim in her vast French repertoire as one of the world’s finest interpreters of Ravel’s Shéhérazade, Berlioz’s Les nuits d’été, and Canteloube’s Les chants d’Auvergne, as well as the orchestrated songs of Debussy and Duparc. She is continually in demand for the symphonic works of the great Austrian and German composers including Mozart and Mahler, as well as the new works of American composers.

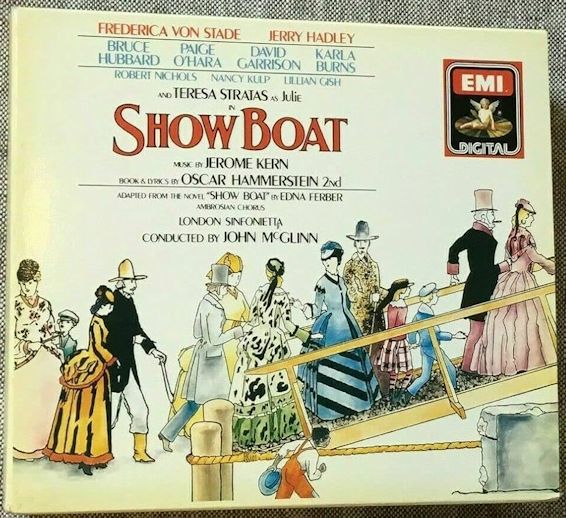

Unparalleled in her artistry as a recitalist, Ms. von Stade combines her expressive vocalism and exceptional musicianship with a rare gift for communication, enriching audiences throughout the world. Here, too, her repertoire encompasses a rich variety, from the classical style of Mozart and Haydn to Broadway; from Italian “Arie antiche” to the songs of contemporary composers who compose especially for her. She has made over seventy recordings with every major label, including

complete operas, aria albums, symphonic works, solo recital programs,

and popular crossover albums. Her recordings have garnered six Grammy

nominations, two Grand Prix du Disc awards, the Deutsche Schallplattenpreis,

Italy’s Premio della Critica Discografica, and “Best of the Year” citations

by Stereo Review and Opera

News. She has enjoyed the distinction of holding simultaneously

the first and second places on national sales charts for Angel/EMI’s Show

Boat and Telarc’s The

Sound of Music. Ms. von Stade appears regularly on television, through numerous PBS and other broadcasts. In 2002 she was seen on national television in a concert with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir as part of the opening ceremonies of the Salt Lake City Winter Olympic Games. In 2001 she participated in the opening of Philadelphia’s Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts performing in a concert together with Sir Elton John, Andre Watts, and the Philadelphia Orchestra. Other highlights of recent television appearances include a gala concert with the San Francisco Symphony to open the 1998-99 season at New York’s Carnegie Hall, and a “Live from Lincoln Center” television event opening the 1999 season of the Mostly Mozart Festival, both broadcast throughout North America. She can be seen in “Live from the Met” performances as Cherubino, Hansel, and Idamante, and through PBS broadcasts of her celebration of the art of American song with Thomas Hampson, Marilyn Horne, Dawn Upshaw and Jerry Hadley in a program at New York’s Town Hall titled “I Hear America Singing,” as well as a program with Tyne Daly which included arias, art songs and popular crossover material. Also seen on PBS were a holiday special, “Christmas with Flicka,” shot on location in Salzburg, “A Carnegie Hall Christmas” with Kathleen Battle, and an evening of operatic and musical theater selections with Samuel Ramey and Jerry Hadley titled “Flicka and Friends.” Her recent portrayals in Dangerous Liaisons and The Aspern Papers were broadcast throughout North America. She can also be seen in the Unitel film of the classic Jean-Pierre Ponnelle production of La cenerentola [shown at the bottom of this webpage.] Ms. von Stade is the holder of honorary doctorates from Yale University, Boston University, the San Francisco Conservatory of Music (which holds a Frederica von Stade Distinguished Chair in Voice), the Georgetown University School of Medicine, and her alma mater, the Mannes School of Music. In 1998 Ms. von Stade was awarded France’s highest honor in the arts when she was appointed as an officer of L’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, and in 1983 she was honored with an award given at The White House by President Reagan in recognition of her significant contribution to the arts == Biography is from the IMG Artists website.

Photos are from another source.

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

© 1987 & 1994 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in Chicago on November 19, 1987, and November 10, 1994. Portions were broadcast on WNIB 1992, 1995, and 2000. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.