|

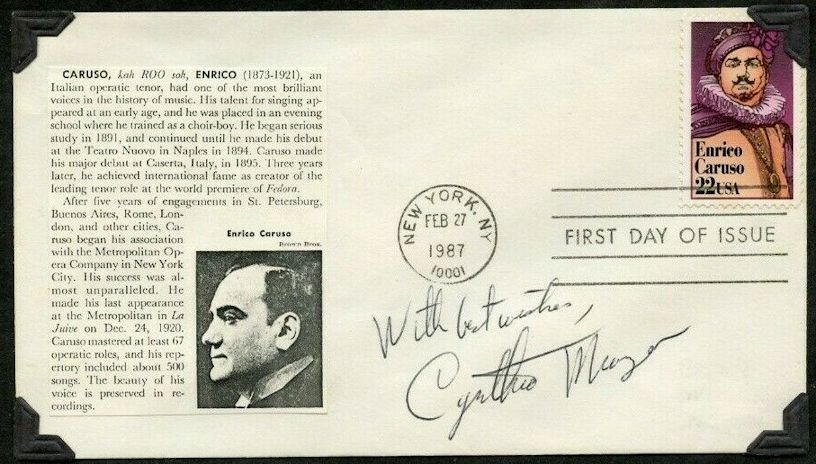

Mezzo-soprano Cynthia Munzer has sung over twenty roles in 223 performances with the Metropolitan Opera, both in New York at the Lincoln Center and on tour in the United States and Japan. Audiences across America have come to know her through the weekly Metropolitan Opera Saturday Broadcasts and over 20 Met Opera recordings with Luciano Pavarotti, Sherill Milnes, Placido Domingo, Joan Sutherland, Monserrat Caballé, Alfredo Kraus, Franco Corelli, Birgit Nilsson and Renata Scotto.

Broadcast

performances have included the Metropolitan Opera Premiere of Alban Berg's

Lulu,

new productions of Bellini's I Puritani

and Verdi's I Vespri Siciliani,

and revivals of Strauss' Salome

and Ariadne auf Naxos,

Gounod's Roméo et

Juliette, Faust,

and Wagner's Die Walküre.

The Metropolitan Opera Gallery of Photos at Lincoln Center displays Ms. Munzer’s

stage photo in its permanent collection. Ms. Munzer has garnered rave reviews as a leading guest artist with over ninety other opera companies and major symphony orchestras. The Dallas Opera, New York City Opera, Washington Opera, L'Opéra de Montréal, Houston Grand Opera, and Florentine Opera have presented Ms. Munzer in diverse roles such as Carmen, Cenerentola, Azucena, Amneris, Dame Quickly, Octavian, Olga, Maddalena, Augusta, and Herodias. The Philadelphia Orchestra, Minnesota Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony, National Symphony, American Symphony, and Hong Kong Philharmonic are among the forty major symphony orchestras with which she has appeared as guest soloist.

Critically acclaimed concert tours with International Artists Inc. to Southeast Asia have resulted in re-engagements with the company in Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, Manila, Jakarta, Penang, Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong.

She

has been hailed in reviews for opera and oratorio performances at the

renowned Wolftrap Festival, Aspen Music Festival, Carmel Bach Festival,

Oregon Bach Festival, Brattleboro Music Festival and the New York Mozart

Bicentennial Celebration. Other highlights of Ms. Munzer's career include

Live

from Lincoln Center broadcasts, vocal concerts at the United Nations,

the world premiere of Gian

Carlo Menotti's Mass,

performances with such masters as Aaron Copland, Leopold Stokowski, James Levine and Zubin Mehta, and a special

9/11 Memorial Tribute CD with other Metropolitan Opera artists. Ms. Munzer is the recipient of the Metropolitan Opera National Council Audition Shared Top Awards presented on the Met stage in New York City, and also a Metropolitan Opera Contract National Winner. Other awards include the Frederick K. Weyerhaeuser Award, Gramma Fisher Foundation Award, Goeran Gentele Award, a Sullivan Foundation Award and Geraldine Farrar Award. She has received keys to the city of Dallas, Texas, and Binghamton, New York, in honor of her artistry.

Born in Clarksburg, West Virginia, Ms. Munzer is a graduate of the University of Kansas. She continued her postgraduate studies with Roy Henderson of the Royal Academy of Music in London, and with former Metropolitan Opera Mezzo Herta Glaz of the Manhattan School of Music in New York City. Currently an Associate Professor Emerita at the Flora L. Thornton School of Music, the University of Southern California, Ms. Munzer has taught and presented master classes in Italy at the Accademia Italiana di Canto in Toscana and the International Lyric Academy, Tuscia Opera Festival in Lazio. She has founded and directed the International Vocal Institute in Hvar, Croatia and co-directed master classes at the Pacific Vocal Institute, part of Bard To Broadway Theatre, Inc. on Vancouver Island, BC. Her students have been winners of the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions, among other competitions, and have appeared in several renowned young artist programs: The Santa Fe Opera, Los Angeles Young Artist Program, Chautauqua Opera, Virginia Opera, and San Diego Opera. Other students have made solo debuts with the Berlin Opera, New York City Opera and the Royal Opera House in London.

Sought after as a master clinician Miss Munzer has within the last several years presented master classes for The Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions in Tucson, AZ, Salt Lake City, UT, St. Paul, MN, Seattle, WA, Vancouver, BC, as well as the Metropolitan Opera Guild Education Series in New York City, the Manhattan School of Music (NYC), The Schubert Club Song Festival in Minneapolis/St. Paul, the National Association of Teachers of Singing Intern Program, NY and Los Angeles and the Spotlight Awards Master Class at The Dorothy Chandler and Disney Hall, LA.

She

has presented celebrity master classes at the Classical Singer Magazine

Convention in New York and Los Angeles. University master classes include

Notre Dame University, Indiana University, Brown University, State University

of New York, Kent State University, and UCLA. Ms. Munzer has expanded

her master classes to several countries and cities: Graz, Austria; Taipei,

Taiwan; Singapore; Hong Kong; Shanghai, China; Paris, France; Hvar, Croatia;

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; Manila, Philippines; Vancouver Island, BC; Monte

Carlo and Viterbo, Italy; Guadalajara, Mexico; and Sydney and Melbourne,

Australia. ==

Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews

elsewhere on my website. BD |

© 1980 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in in the studios of WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago on March 6, 1980. Portions were broadcast on WNIB five days later. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.