|

*

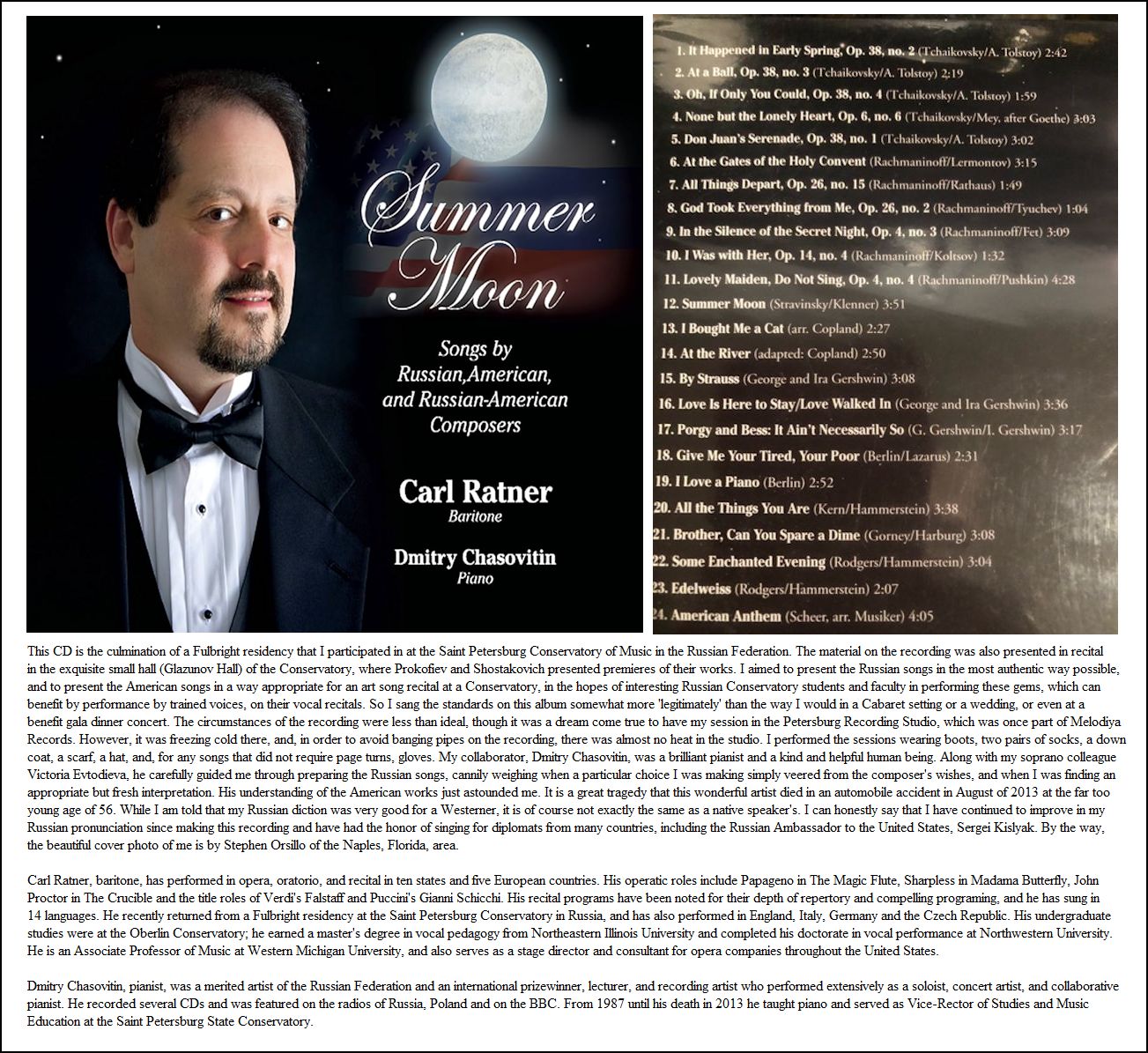

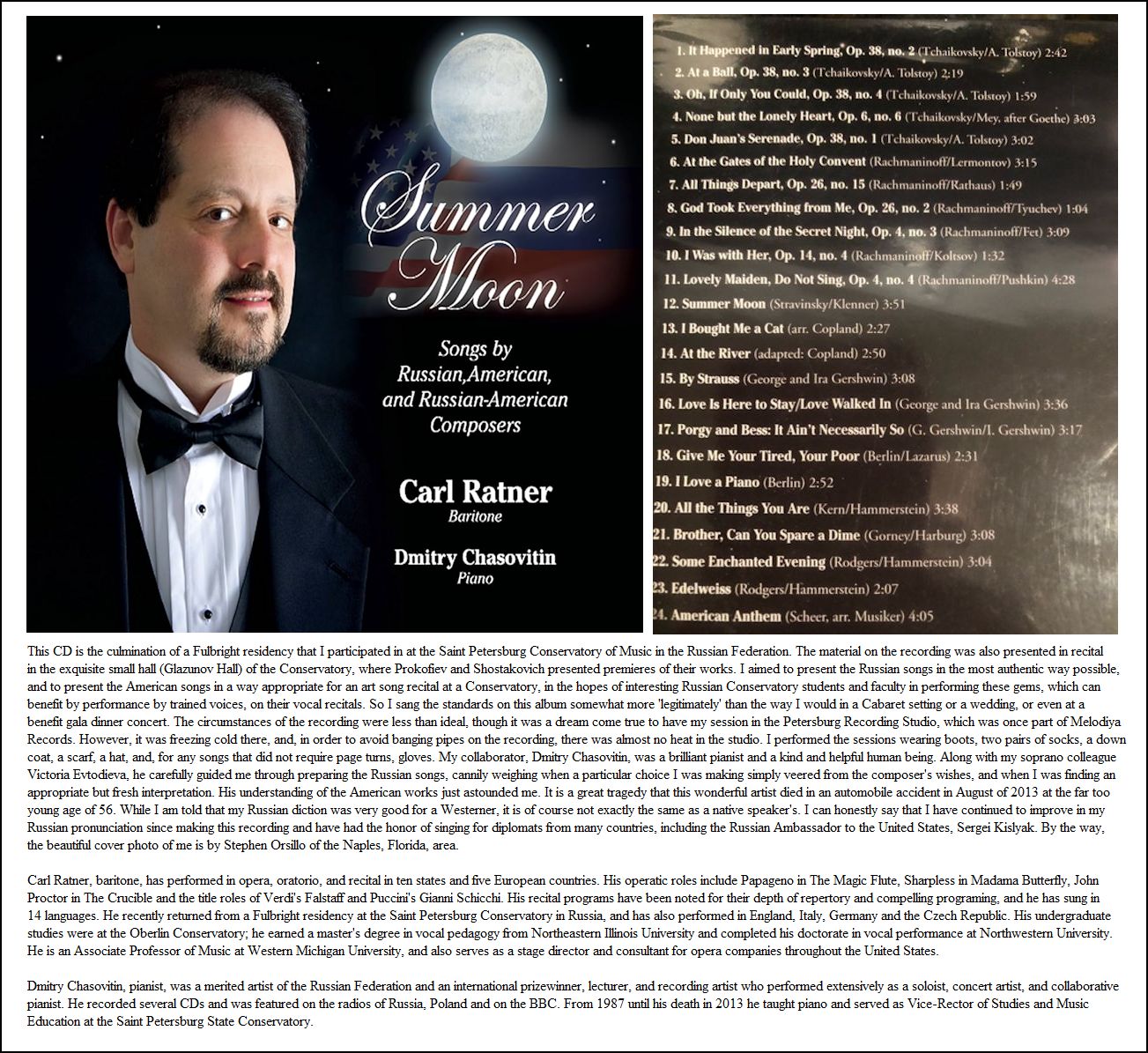

Chamber Opera Chicago's 1st season was Spring, 1983.

I arrived the following Spring.

* In

summer, 1993, Chamber Opera Chicago went 'dark', and Carl Ratner and

I moved directly to Chicago Opera Theater. We were Artistic Administrator

and Resident Conductor during our trial season

with COT, Spring, 1994.

After the success of Beatrice and Benedict and The Ballad

of Baby Doe, we were immediately appointed as Artistic and Music

Directors. [For more about these two productions, see my interviews

with director Marc Verzatt

(and Rapchak), and conductor Ted Taylor (and Ratner).

Also, biographies and photos of Rapchak and Ratner can be found on those

two webpages.] We both left COT in the Spring of 2000.

* During

the Ratner/Rapchak years of Chamber Opera Chicago, we always performed

at the Ruth Page Auditorium EXCEPT for the Spring season of

1988, when the hall was undergoing remodeling to bring the place up to

code. By some lucky break, I happened to walk into the Page theater in

January, '88 to check on something, when the guy at the desk casually

informed me,

"Oh, glad you stopped by. There's something that I've been meaning

to call and discuss with you guys. The city is closing the joint

down for code

violations, so you won't be able to perform here in April." It

was a good thing I walked in that day, and the scramble to save our season

was on. We ended up that year ('88) in the IVANHOE Theater (which

had a

popular liquor store attached, as I recall) for successful productions

of

Traviata and Barber of Seville.

--------------------------------- NOTE-- For the record, Chamber Opera Chicago started up anew under the artistic direction of Barbara Seid. Among other works, they've performed an annual "Amahl and the Night Visitors" at the Athaneum and elsewhere for many years now (since 2005). ==

Names which are links in this box and throughout this webpage refer

to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

Stuart Leitch is a pianist, organist, and teacher active in Michigan

and Chicago. He studied with Arthur Dann at Oberlin College and privately

with John Richardson, Gui Mombaerts, Dmitry Paperno, and Donald

Walker.

Stuart Leitch is a pianist, organist, and teacher active in Michigan

and Chicago. He studied with Arthur Dann at Oberlin College and privately

with John Richardson, Gui Mombaerts, Dmitry Paperno, and Donald

Walker. From 1962 to 1965 he was a member of the ONCE group in Ann Arbor, whose concerts featured prominent avant-garde composers and performers from all over the world. Later in New York City he transcribed books of country blues and worked with The Children of Paradise, recording and creating film music. During his long career in Chicago he coached singers and worked with Lyric Opera of Chicago and Chicago Opera Theater. He founded and directed Chamber Opera Chicago, and served as staff accompanist at Northern Illinois University in DeKalb. He is also active as a pianist, with performances in the Dame Myra Hess Memorial Concerts, and solo broadcasts by WFMT-FM. He played and recorded several new works by George Flynn, and has performed twice as a featured pianist with Grand Rapids Ballet. He performs in the annual Schubertiade Chicago, and is artistic advisor of Schubertiade Oak Park at Unity Temple. He also works as a music engraver, editor, and arranger for several composers, refining their music and publishing their scores. Leitch is also the inventor and publisher of Deep Solitaire, a game application for Android phones and tablets. He lives in semiretirement near his family in Grand Rapids and plans to spend the rest of his life deepening his understanding of the musical art, for the glory of God and the refreshment of the human spirit. == Biography (slightly edited) and photo from

the Handel Week Festival website

|

The American tenor, Lawrence Johnson, has degrees in both voice and piano performance. He was an international finalist in the Luciano Pavarotti International Voice Competition in Philadelphia. Other awards include the Wisconsin State NATS Winner, and regional finalist in the Metropolitan Opera Auditions. Lawrence Johnson has sung extensively throughout the Midwest and Southwest, as well as such diverse venues as Munich, Germany and Disneyworld. He has had the privilege of working with such distinguished luminaries as Sherrill Milnes, Mignon Dunn, Martin Katz, Elly Ameling, Geoffrey Parsons, and Tony Randall. He has also accompanied numerous concerts, operas, recitals, and shows. Among his many operatic roles performed, Rodolfo, Werther, and Don José remain his all time favorites. He continues to actively concertize locally and regionally with groups such as the Orchestra of Southern Utah, in oratorio, opera, and recital performances. Lawrence Johnson serves as Associate Professor of Music at Southern Utah University. * * *

* *

Mezzo-soprano Amy Ellen Anderson is a versatile performer whose work in opera, song recital and oratorio has taken her throughout the United States and to Europe and Asia.

Her operatic credits encompass a wide range of roles and musical styles from Baroque performances of La Messagiera in Monteverdi's Orfeo, to standard repertoire including the title role in Carmen, Rosina in the Barber of Seville, Lucretia in the Rape of Lucretia, Charlotte in Werther, and Maddalena in Rigoletto among others. She has appeared in several new operas including Patience and Sarah by Paula Kimper with American Opera Project and Steel Grin by Peter Aglinskas with Chicago Opera Theater. Her musical theater credits include the role of Anna in The King and I. In addition to her interest in opera, Ms. Anderson enjoys performing concert and song repertoire and has worked with American composer William Bolcom in a recital of his music in New York City. She has been a guest artist with the contemporary chamber music group Continuum. She has been featured with the Aldeburgh Festival in England, the Lincoln Center Festival, Opera Delaware, the West Virginia Symphony, Aspen Opera Theatre, Glimmerglass Opera, the Ashlawn-Highland Festival, Waco Opera, the Pacific Music Festival in Japan, Chicago Opera Theater, and Sarasota Opera. She has received the American Opera Society Award, The Union League Club Scholarship, the Farwell Award from the Musician's Club of Women and the Lynne Harvey Award. She is the alto soloist on a Naxos CD of Mozart's Requiem with the St. Clement Choir and Orchestra. Ms. Anderson holds Master of Music and Bachelor of Music degrees from Northwestern University. * * *

* *

Further appearances include Taddeo/L’italiana in Algeri

(Hawaii Opera Theatre), the Vicar/ Albert Herring (Cleveland Opera),

title role/ Rigoletto (Minnesota Opera), Salieri/Rimsky-Korsakov’s

Mozart and Salieri (Fort Wayne Philharmonic), Douphol/La

traviata (with Renée

Fleming at Los Angeles Opera, released on DVD), and Mangus/Sir Michael

Tippett’s The Knot Garden (American premiere). Since 1990-91,

Kraus has sung 24 roles with Lyric Opera of Chicago, including Notary/Der

Rosenkavalier, the Bailiff Werther, Antonio Marriage of Figaro,

and Bartolo Barber of Seville. Kraus is active in the concert hall having made multiple appearances singing Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, Orff’s Carmina Burana, Brahms’s A German Requiem, and Verdi’s Requiem with orchestras throughout the United States. He made his UK debut in recital at Norwich Cathedral. |

© 1989 & 1991 Bruce Duffie

These conversations was recorded in Chicago on August 22, 1989, and April 23, 1991. Portions were broadcast on WNIB a few days after each meeting. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.