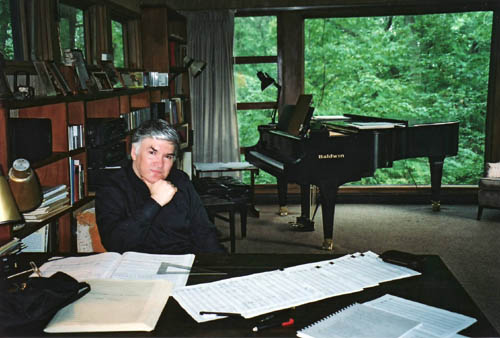

[Photo taken at the Copland House, Peekskill, NY, 2001]

|

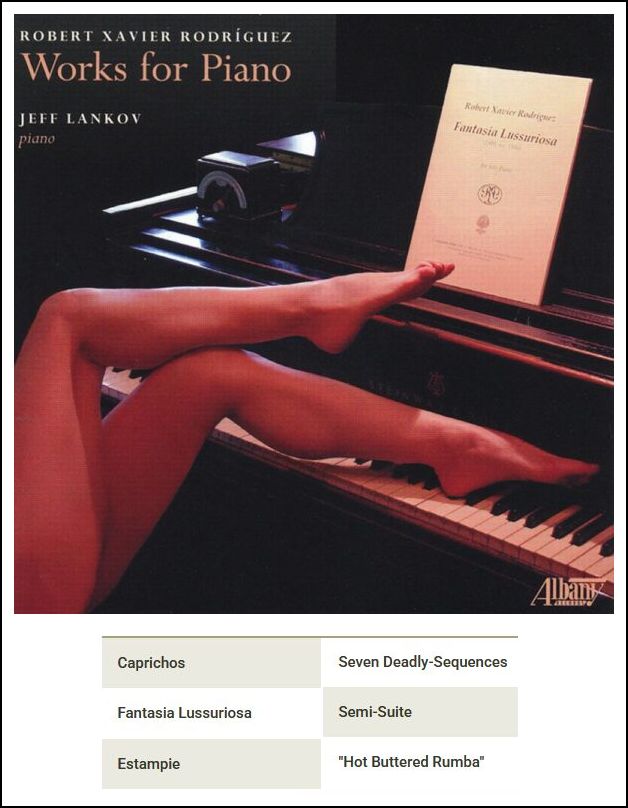

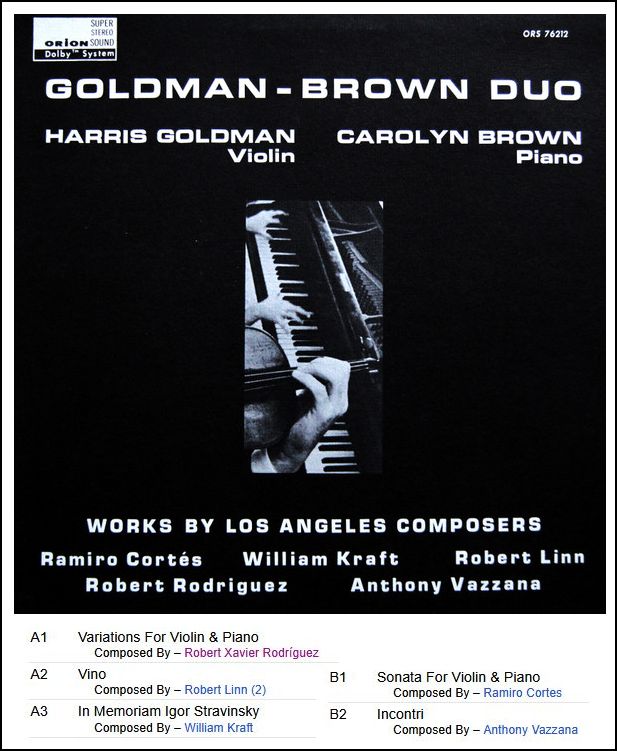

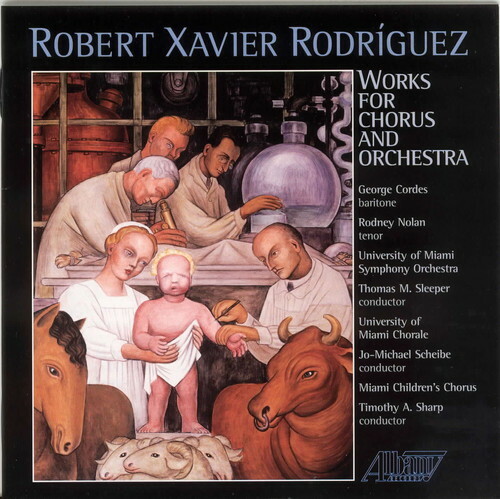

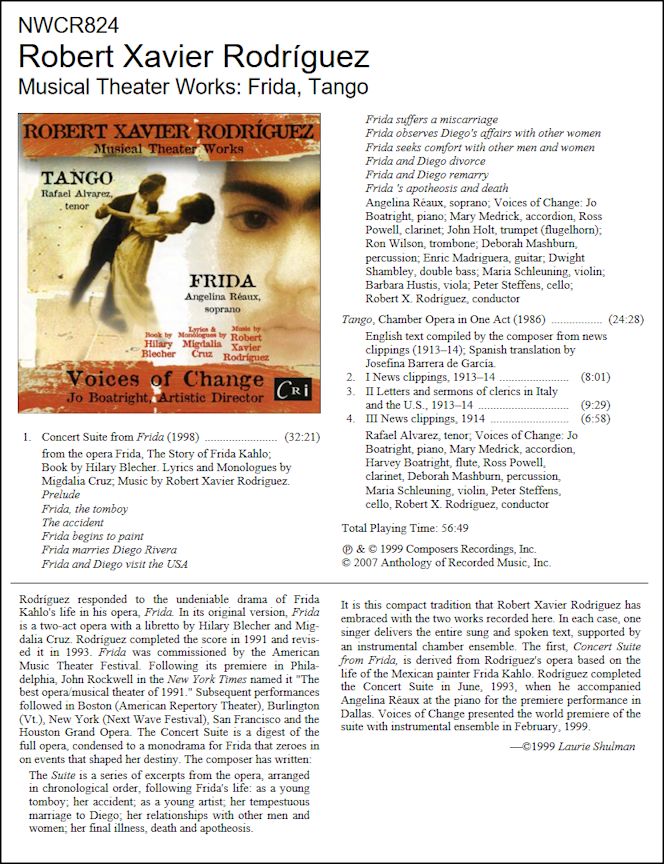

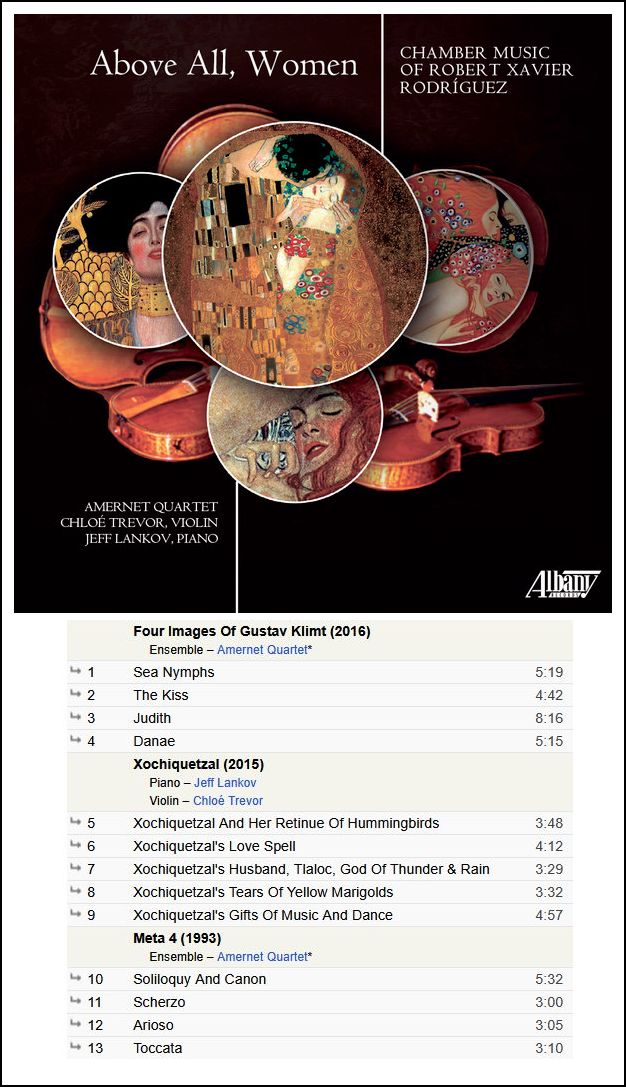

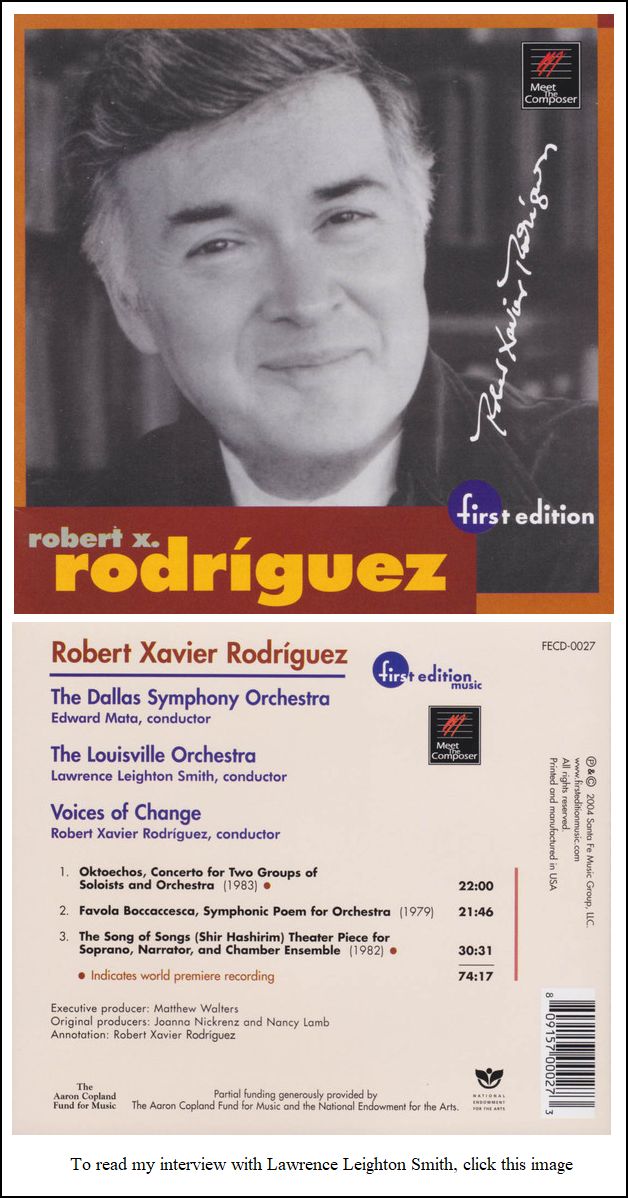

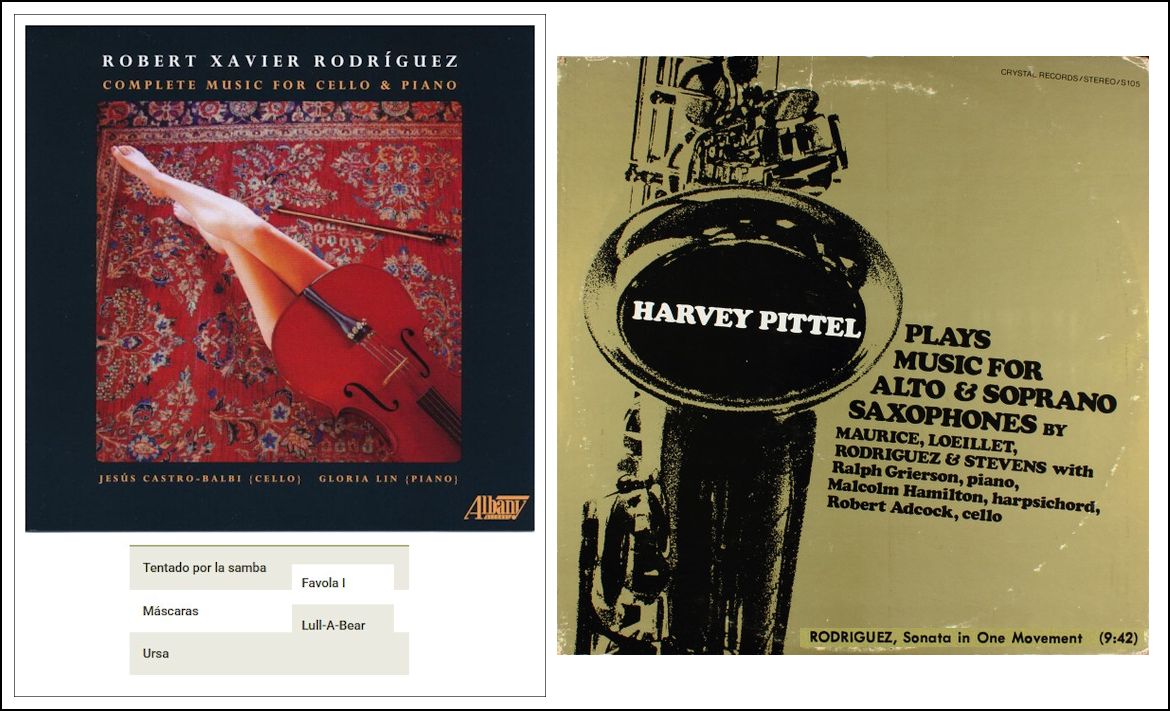

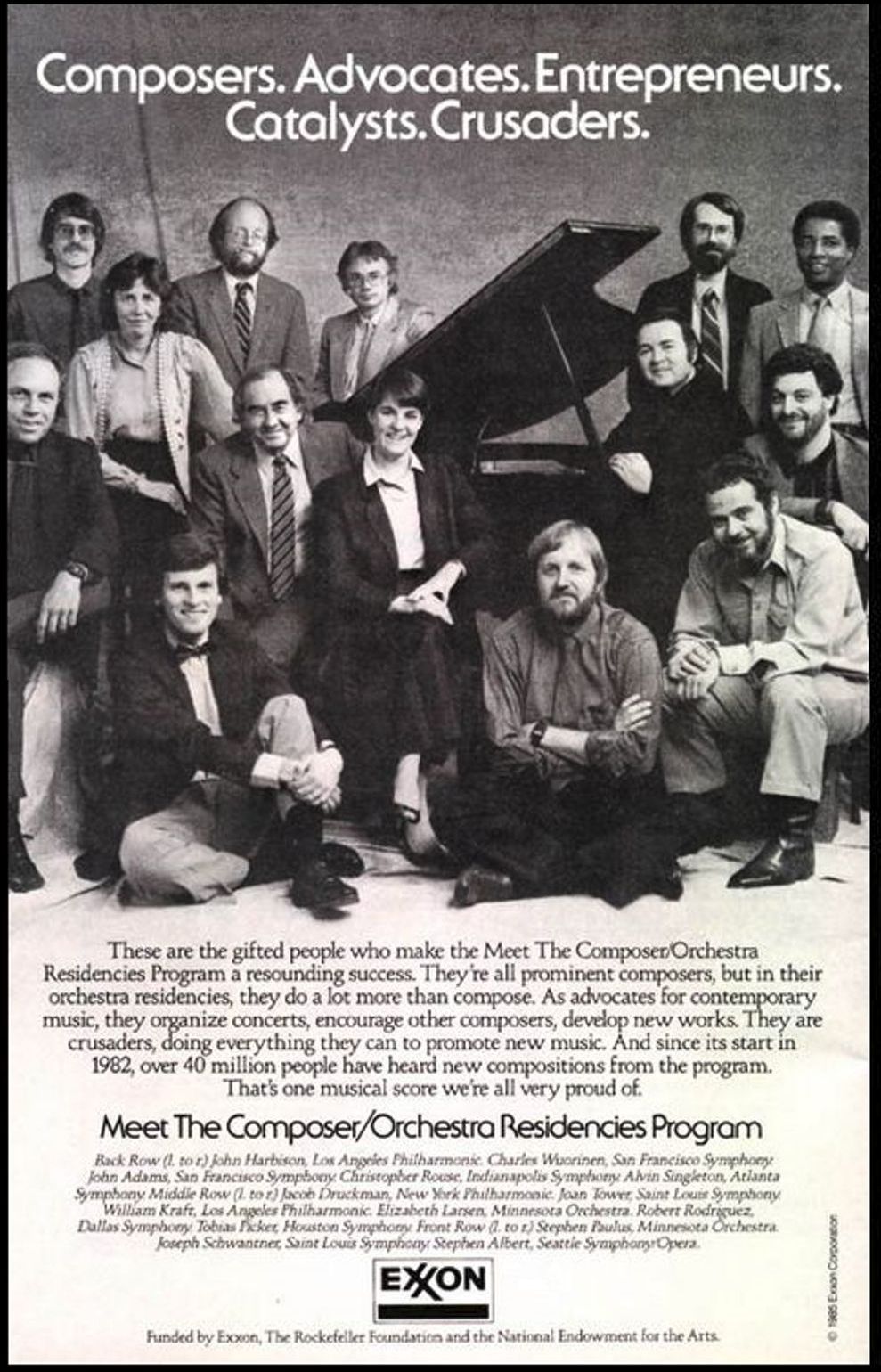

Rodríguez (born June 28, 1946) received his early musical education in San Antonio and in Austin (UT), Los Angeles (USC), Lenox (Tanglewood), Fontainebleau (Conservatoire Américain) and Paris. His teachers have included Nadia Boulanger, Jacob Druckman, Bruno Maderna and Elliott Carter. Rodríguez first gained international recognition in 1971, when he was awarded the Prix de Composition Musicale Prince Pierre de Monaco by Prince Rainier and Princess Grace at the Palais Princier in Monte Carlo. Other honors include the Prix Lili Boulanger, a Guggenheim Fellowship, awards from ASCAP and the Rockefeller Foundation, five NEA grants and the Goddard Lieberson Award from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. Rodríguez has served as Composer-in-Residence with the San Antonio Symphony and the Dallas Symphony. He currently holds the Endowed Chair of University Professor at The University of Texas at Dallas, where he is Director of the Musica Nova ensemble. He is active as a guest lecturer and conductor. Rodríguez’ music has been performed by conductors such as Sir Neville Marriner, Antal Dorati, Eduardo Mata, James DePreist, Sir Raymond Leppard, Keith Lockhart and Leonard Slatkin. His work has received over 2000 professional orchestral and operatic performances in recent seasons by such organizations as the Vienna Schauspielhaus, The National Opera of Mexico, New York City Opera, Brooklyn Academy of Music, American Repertory Theater, American Music Theater Festival (now Prince Music Theater), Dallas Opera, Houston Grand Opera, Pennsylvania Opera Theater, Michigan Opera Theatre, Orlando Opera, The Aspen Music Festival, The Bowdoin Festival, The Juilliard Focus and Summergarden Series, The Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Mexico City Philharmonic, Toronto Radio Orchestra, American Composers Orchestra, The Baltimore, Dallas, Houston, San Antonio, Knoxville, Indianapolis, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Milwaukee, Boston and Chicago Symphonies, The Los Angeles Philharmonic, National Symphony, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, Louisville Orchestra and Cleveland Orchestra. Rodríguez' chamber works have been performed in London, Paris, Dijon, Monte Carlo, Berlin, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Edinburgh, The Hague and other musical centers. His music is published exclusively by G. Schirmer and is recorded on the Newport, Crystal, Orion, Gasparo, Pro Arte, ACA, Urtext, CRI (Grammy nomination), First Edition, Schott, Naxos and Albany labels. == Text of biography from the composer’s official

website [with correction]

== Names which are links in this box (and below) refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 19, 1998. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year; on WNUR in 2011, and 2014; and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2011. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.