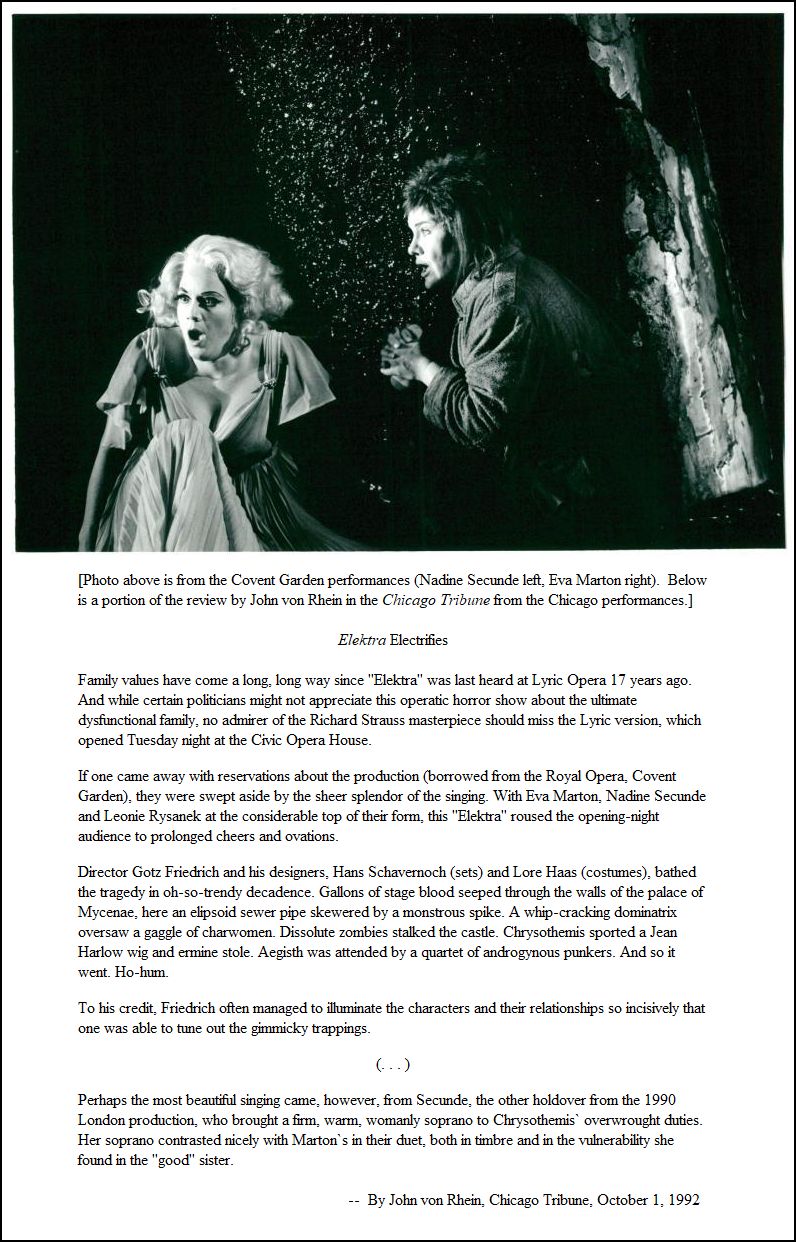

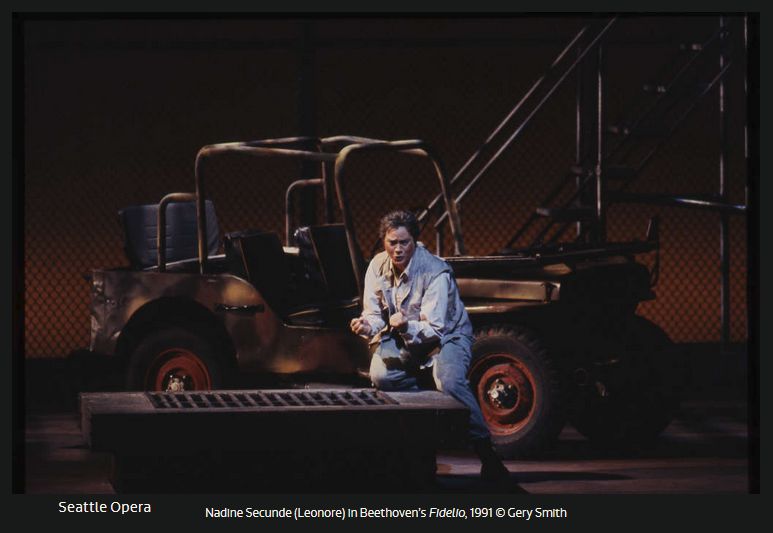

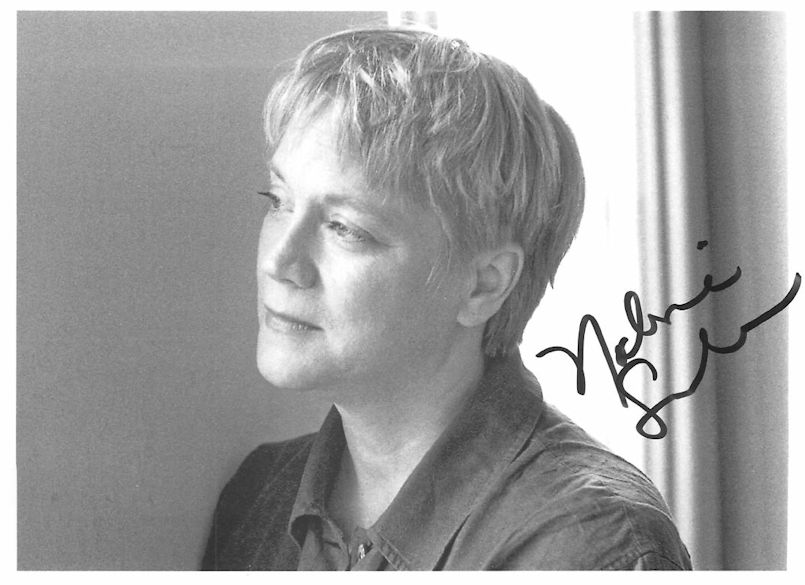

| American soprano Nadine Secunde (born

December 21, 1953 in Independence, near Cleveland, Ohio) studied at

Oberlin Conservatory, at Indiana University with Margaret Harshaw, and

at the Musikhochschule in Stuttgart with a Fulbright Scholarship.

She has become a leading artist in the world's finest opera

houses in the demanding Strauss and Wagner repertoire. Critical acclaim

for her ”glowing, blooming soprano” and her ”brilliant character portrayal”

has been ratified by tremendous popular success and reengagements by

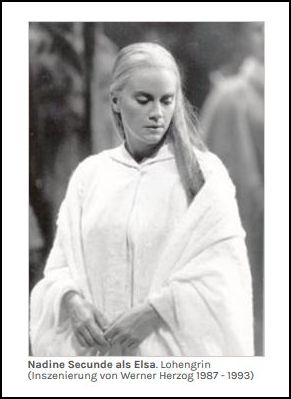

the theaters in which she appears. She made a triumphant debut at the

Bayreuth festival in 1987 as Elsa in a new production of Lohengrin

by the noted German film director Werner Herzog. The following summer

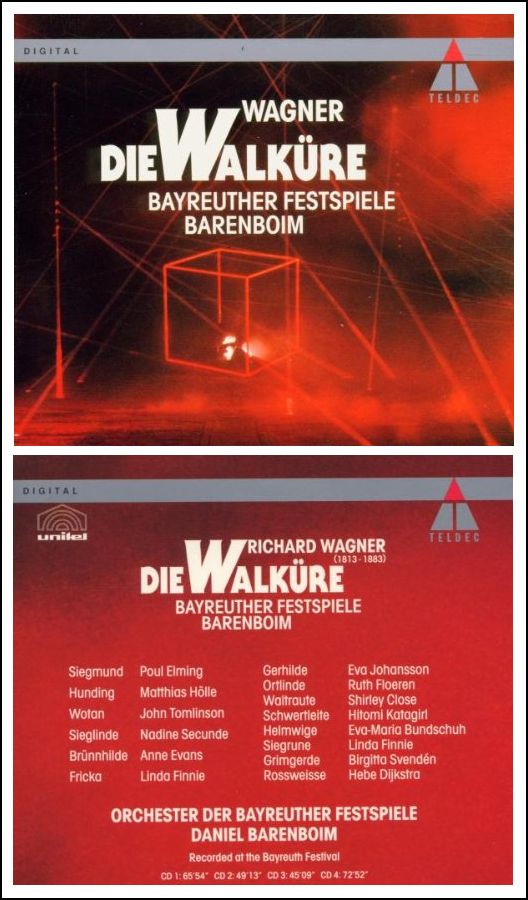

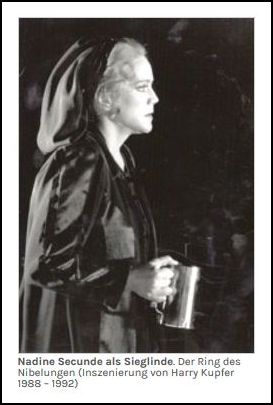

she scored a great personal success at Bayreuth as Sieglinde in Harry

Kupfer's controversial production of Die Walküre conducted

by Daniel Barenboim

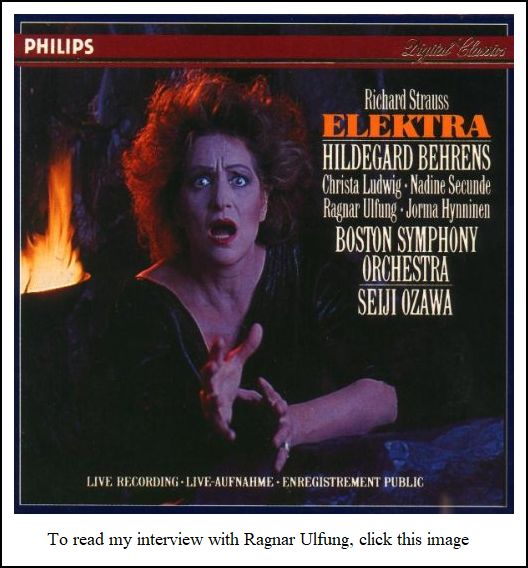

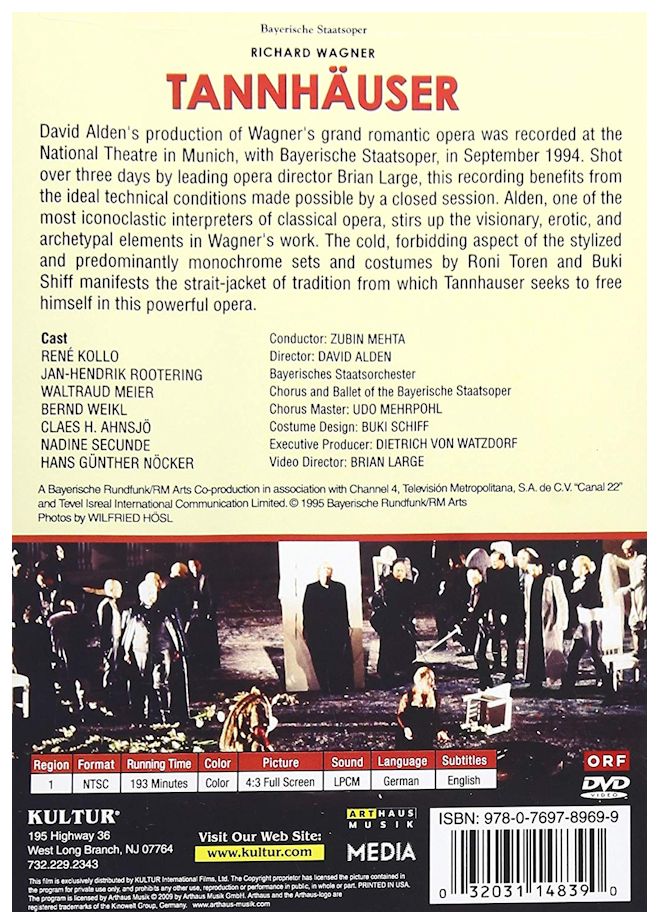

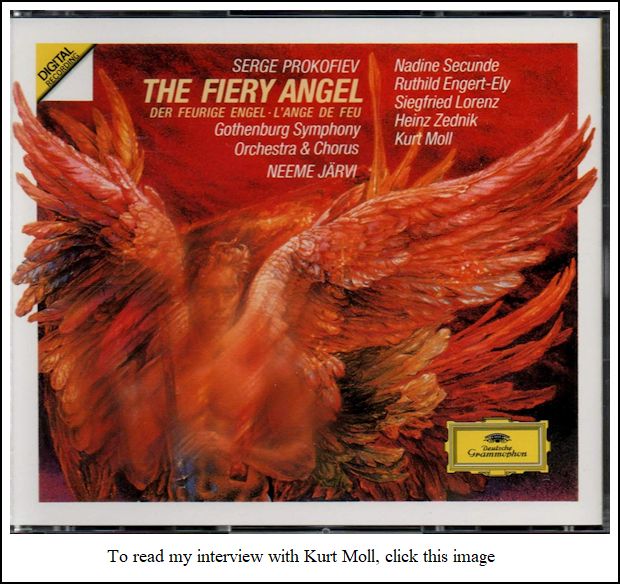

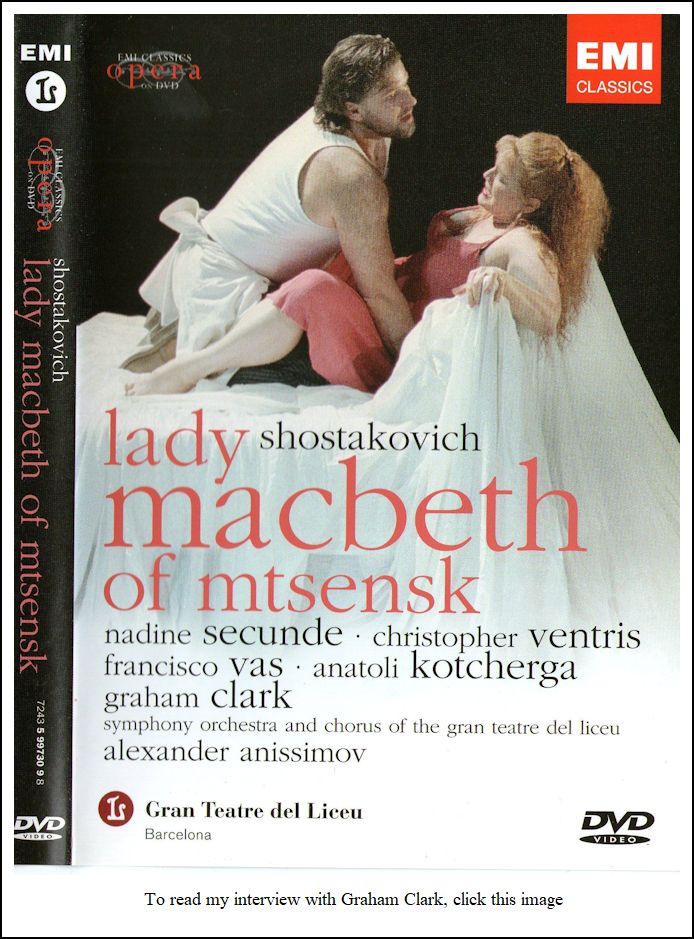

which has been recorded for audio and video. Since her Bayreuth debut she has appeared in many of Europe's great theaters. In Munich she has sung the role of Elisabeth in Tannhäuser conducted by Zubin Mehta. In Hamburg she appeared in the title role of Katya Kabanova and as Isolde; her debut in Vienna was as Sieglinde; there she has also sung Elisabeth in Tannhäuser and Chrysothemis in Elektra. In this role she made her Paris debut with Seiji Ozawa conducting, and in Covent Garden with Sir Georg Solti. Anthony Papano conducted her first Lady Macbeth of Msenk in Brussels, and she was privileged to take part in the world premiere of Venus und Adonis by Hans Werner Henze as The Primadonna, conducted by Markus Stenz. Her American debut took place at the Lyric Opera of Chicago is Peter Sellar's highly acclaimed production of Tannhäuser. Other important engagements have included her Los Angeles debut as Cassandre in Les Troyens, and her San Francisco debut as Chrysothemis, conducted by Christian Thielemann. In Seattle she sang her first Brünnhilde in the 1997 Ring, and her first Marschallin. Since then she has garnered critical acclaim and enormous public reaction in her ”new” repertoire. Her first Bünnhilde in Die Götterdämmerung in Amsterdam is 1999 was greeted with ”an unimaginable outpouring of audience jubilation” Her debut as Elektra in the prestigious ”Leonie Rysenek Memorial Production” in Marseille was a stunning success with audience and critics, leading to new productions scheduled in Tokyo and Amsterdam in 2006. Important orchestral engagements have included her American debut with the Los Angeles Philharmonic under André Previn in Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, which she also sang in Paris with Daniel Barenboim and in Rome with Christian Thielemann. She took part in the Towards the Millenium concert series in London's Royal Festival Hall as the soloist in Berg's Seven Early Songs conducted by Simon Rattle. Her Italian concert debut was a celebrated performance of Britten's War Requiem with Wolfgang Sawallisch. In the spring of 2000 she sang a concert performance of Die Walküre in the recently renovated Teatro Lyceo in Barcelona with Placido Domingo. Miss Secunde made her recording debut as Chrysothemis in a concert performance of Elektra with Hildegard Behrens in the title role. Seiji Ozawa conducted the Boston Symphony in the Philips release. She also recorded the demanding role of Renata in Prokoviev's The Fiery Angel for DGG, with Neeme Järvi conducting the Goteborg Symphony Orchestra, The Turn of the Screw by Benjamin Britten for Naxos, and a complete video recording of Elisabeth in Tannhäuser conducted by Zubin Mehta, with René Kollo and Waltraud Meier. -- From her official website (with slight

corrections and additions)

-- In this box and throughout this webpage, names which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

NS: [Thinks a moment] I don’t

know. There are two points of view on it. It’s certainly

wonderful to hear an idealized performance of a piece with everything

as good as it could be. The only thing that worries me a little bit is

that it may lead our normal public to believe that that’s what they’re

going to hear when they go to the opera, which is – let’s say – both too

much and too little demanded of the cast. Too much in the sense that

we’re regular human beings. People have off-days and on-days. Sometimes

it’s really great, and sometimes it’s maybe less than great. And

too little in the sense that the record gives you no feeling of spontaneity

whatsoever. It’s completely canned. There’s very little

feeling of the drama that comes across, and most of us never give that

stale a performance on stage. So, recordings have been a real blessing

and a real curse for singers everywhere.

NS: [Thinks a moment] I don’t

know. There are two points of view on it. It’s certainly

wonderful to hear an idealized performance of a piece with everything

as good as it could be. The only thing that worries me a little bit is

that it may lead our normal public to believe that that’s what they’re

going to hear when they go to the opera, which is – let’s say – both too

much and too little demanded of the cast. Too much in the sense that

we’re regular human beings. People have off-days and on-days. Sometimes

it’s really great, and sometimes it’s maybe less than great. And

too little in the sense that the record gives you no feeling of spontaneity

whatsoever. It’s completely canned. There’s very little

feeling of the drama that comes across, and most of us never give that

stale a performance on stage. So, recordings have been a real blessing

and a real curse for singers everywhere. BD: Did you start out as a German singer, or as an all-round

singer?

BD: Did you start out as a German singer, or as an all-round

singer? NS: I personally would say the technique never ever lets

go. It becomes part of the artistry. In an ideal world, we

would like people not to be aware of what we do. We like to be magicians

and say, “Watch me pull this rabbit out

of the hat,” and they will never know how I do

it. But sometimes it’s just a little bit too hard, and

I have not found it a good thing if you make an audience aware of how

hard it is. If they can really see your concentration, then it has

a negative effect on them. On the other hand, they tend really to

appreciate it. I remember very vividly a master class my teacher

once did. A tenor was singing a really hard aria, and she said, “Why

are you trying to make this look easy? It isn’t!”

People appreciate the effort that you’re giving them. If they

think it’s too easy, they say, “Well, I can

do that!” Let’s take the Prayer in

Tannhäuser, which is one of the most difficult things to sing

in the Wagnerian repertoire, simply because of the intonation. It’s

me against the woodwinds, and they’re sometimes playing in several different

keys... not in this orchestra, but it happens. You’re concentrating

like a laser beam, trying to focus in on exactly what you’re doing, and

people pick that up. It produces a vibration that they appreciate.

NS: I personally would say the technique never ever lets

go. It becomes part of the artistry. In an ideal world, we

would like people not to be aware of what we do. We like to be magicians

and say, “Watch me pull this rabbit out

of the hat,” and they will never know how I do

it. But sometimes it’s just a little bit too hard, and

I have not found it a good thing if you make an audience aware of how

hard it is. If they can really see your concentration, then it has

a negative effect on them. On the other hand, they tend really to

appreciate it. I remember very vividly a master class my teacher

once did. A tenor was singing a really hard aria, and she said, “Why

are you trying to make this look easy? It isn’t!”

People appreciate the effort that you’re giving them. If they

think it’s too easy, they say, “Well, I can

do that!” Let’s take the Prayer in

Tannhäuser, which is one of the most difficult things to sing

in the Wagnerian repertoire, simply because of the intonation. It’s

me against the woodwinds, and they’re sometimes playing in several different

keys... not in this orchestra, but it happens. You’re concentrating

like a laser beam, trying to focus in on exactly what you’re doing, and

people pick that up. It produces a vibration that they appreciate. NS: Yes, almost exclusively.

NS: Yes, almost exclusively. NS: I loved the way she was this summer

because she was great. She was so sexy, and so aggressive at

the same time, which was fascinating for me.

NS: I loved the way she was this summer

because she was great. She was so sexy, and so aggressive at

the same time, which was fascinating for me. BD: You’ve sung in all of these various

houses, and then you get dropped into Bayreuth, with that hood over the

orchestra. How does that change the way you produce the sound,

or the way you hear the sound?

BD: You’ve sung in all of these various

houses, and then you get dropped into Bayreuth, with that hood over the

orchestra. How does that change the way you produce the sound,

or the way you hear the sound? BD: ...or Paris and Paris?

BD: ...or Paris and Paris?  BD: You can separate what’s in your

throat from the rest of you?

BD: You can separate what’s in your

throat from the rest of you?

BD: Some of the ladies that are portrayed on the

stage are the old-fashioned helpless woman who are victims, but you

don’t do too many of those.

BD: Some of the ladies that are portrayed on the

stage are the old-fashioned helpless woman who are victims, but you

don’t do too many of those.© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago, on October 15, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB three days later. This transcription was made in 2018, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.