A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Kurt Adler, Conductor Who Led San Francisco Opera,

Dies at 82

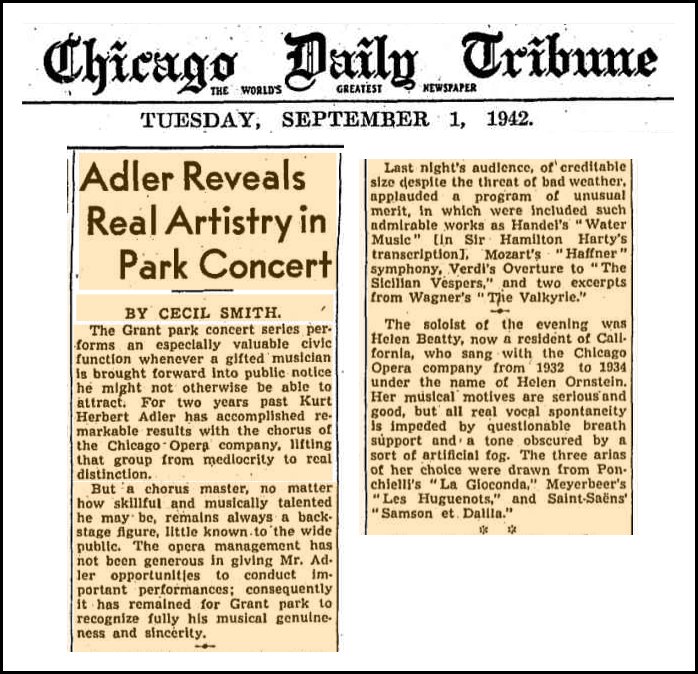

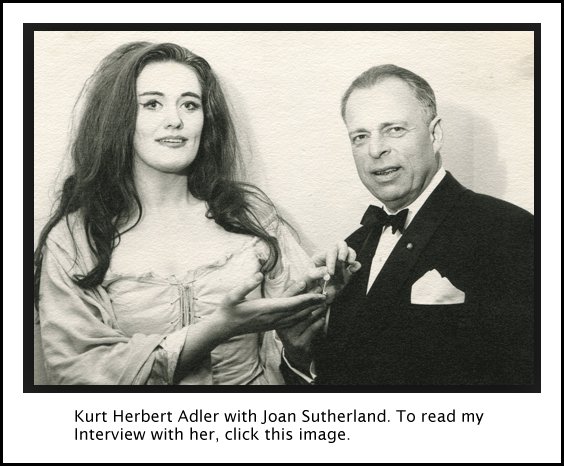

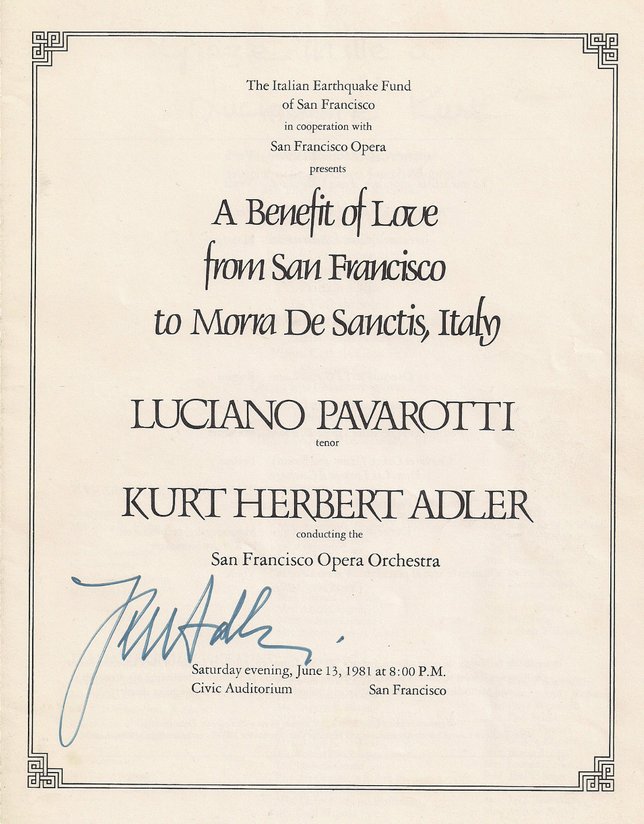

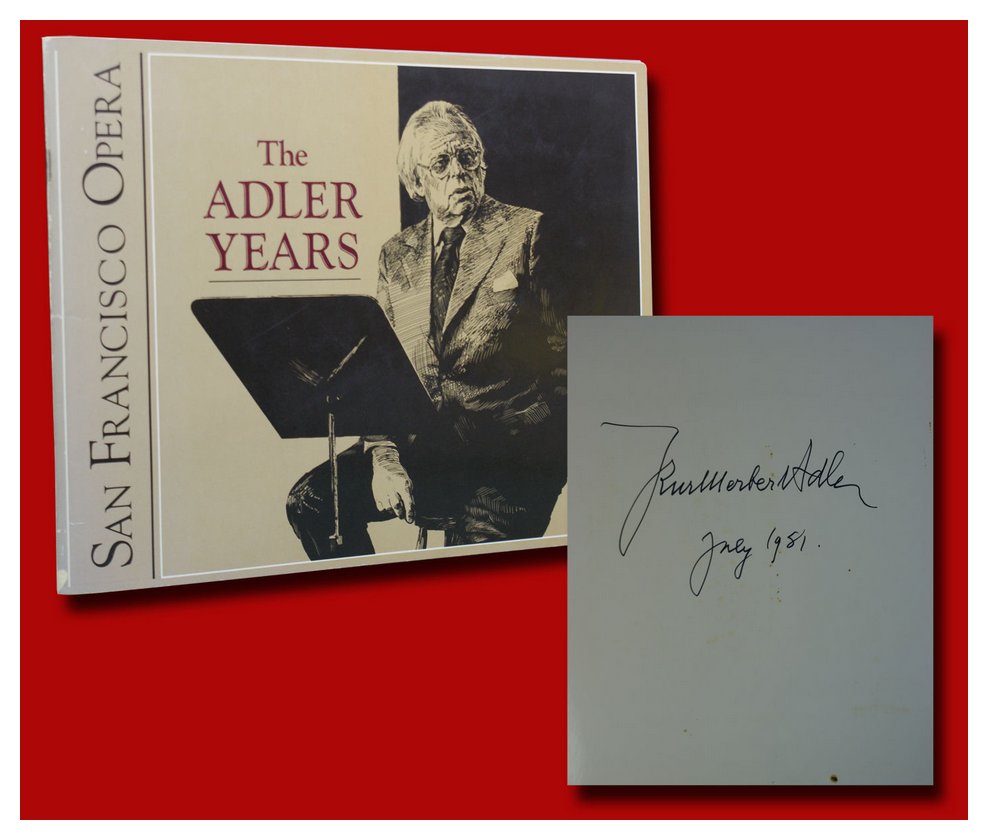

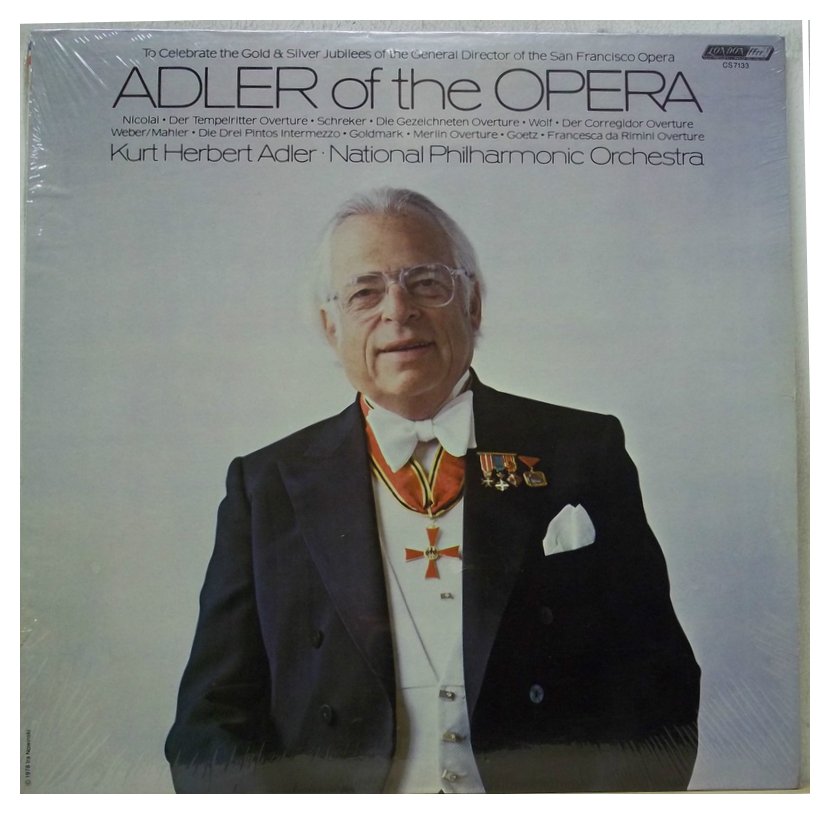

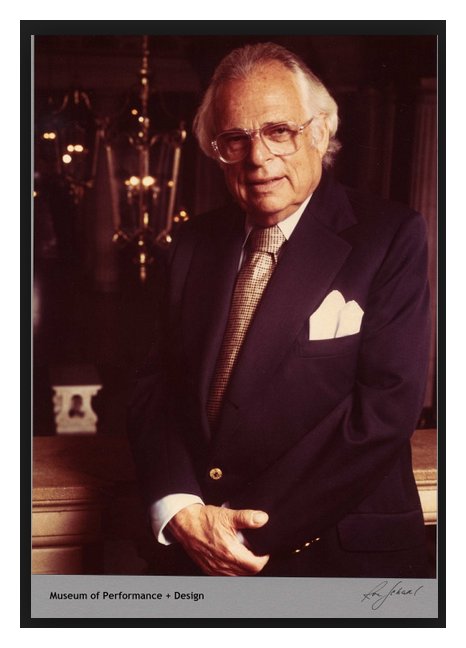

By JOHN ROCKWELL Published: February 11, 1988 in The New York Times [Text only - links added for this website presentation] Kurt Herbert Adler, a Viennese-born conductor who led the San Francisco Opera for 28 years until his retirement in 1981, died of a heart attack Tuesday evening at his home in Ross, Calif., a suburb north of San Francisco. He was 82 years old. Mr. Adler's death followed by only a few hours the announcement that his successor, Terence A. McEwen, would retire because of acute diabetes. During his tenure with the company, Mr. Adler shaped it into one of the leading opera ensembles of the world. The San Francisco Opera was founded in 1923 by Mr. Adler's predecessor, Gaetano Merola, who had a natural predilection for Italian repertory. Mr. Adler brought a different spirit, more oriented toward German repertory, modernism and innovative stage direction. He expanded the repertory, introduced many young singers both European and American, developed summer, apprentice and touring programs and presided over a vast expansion of the season and the budget. An imperious, crusty figure who involved himself with every aspect of the company's operations, Mr. Adler personified opera in San Francisco during the 1950's, 60's and 70's. A brooding bust of the general director, arms crossed and scowling like Beethoven, was installed in the lobby of the War Memorial Opera House long before his retirement. Born in 1905 in Vienna and educated at the academy and university, Mr. Adler made his debut as a conductor in 1925 at Max Reinhardt's theater in his native city. He subsequently conducted in opera houses in Germany, Italy and Czechoslovakia, and assisted Arturo Toscanini at the 1936 Salzburg Festival. Emigrating to the United States in 1938, initially for an engagement at the Chicago Opera, he became a United States citizen in 1941. In 1943 he joined the staff of the San Francisco Opera as chorus master, at first commuting from New York. He was appointed artistic director in 1953 and general director in 1956. Following his retirement on Dec. 31, 1981, he was named general director emeritus. When Mr. Adler took over the company in 1953, its season lasted five weeks. At his retirement, it stretched from Labor Day through December, with added spring and summer seasons. Operas given their American premieres during his tenure included Britten's ''Midsummer Night's Dream,'' Richard Strauss's ''Frau Ohne Schatten'' and Poulenc's ''Dialogues of the Carmelites.'' In addition to an unusually wide range of standard and not-so-standard repertory, other novelties included Cherubini's ''Portuguese Inn,'' Honegger's ''Joan of Arc at the Stake,'' Walton's ''Troilus and Cressida,'' Orff's ''Wise Maiden,'' Norman Dello Joio's ''Blood Moon,'' Shostakovich's ''Katerina Ismailova,'' Robert Ward's ''Crucible,'' Douglas Moore's ''Carry Nation,'' Gunther Schuller's ''Visitation,'' Aribert Reimann's ''Lear'' and a triple bill of the Weill-Schuller ''Royal Palace,'' Schoenberg's ''Erwartung'' and the ''Discovery of America'' portion of Milhaud's ''Christopher Columbus.'' More than 300 singers, conductors, directors and designers made their American debuts with the San Francisco Opera under Mr. Adler's auspices. They included Boris Christoff, Geraint Evans, August Everding, Tito Gobbi, Sena Jurinac, Pilar Lorengar, Mario Del Monaco, Birgit Nilsson, Jean-Pierre Ponnelle, Leontyne Price, Margaret Price, Mstislav Rostropovich, Leonie Rysanek, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Giulietta Simionato, Georg Solti and Renata Tebaldi. Although he was primarily an administrator during his years as director of the San Francisco company, Mr. Adler also conducted occasionally. He continued to guest-conduct periodically after 1981, in San Francisco and elsewhere, and taught at San Francisco State University. His awards and honors included the Star of Solidarity from Italy, the Officer's Cross of West Germany and the Great Order of Merit of Austria. Mr. Adler is survived by his wife, Nancy; two daughters, Kristin Krueger of Clayton, Calif., and Sabrina, of Ross; two sons, Ronald, of Munich, West Germany, and Roman, of Ross, and two grandchildren. -- Note: Links throughout this

page refer to my Interviews elsewhere on this website. BD

|

Now back to Kurt Herbert Adler. He was born in Vienna and educated

at the Musikakademie and the university there, making his debut at the age

of twenty conducting the Max Reinhardt Theater. He rose through the

ranks, and, like so many others who were being persecuted in Europe at that

time, he came to the US in 1938. First in Chicago, then in San Francisco,

he left his mark on many productions, and made the company of the City on

the Bay his own.

Now back to Kurt Herbert Adler. He was born in Vienna and educated

at the Musikakademie and the university there, making his debut at the age

of twenty conducting the Max Reinhardt Theater. He rose through the

ranks, and, like so many others who were being persecuted in Europe at that

time, he came to the US in 1938. First in Chicago, then in San Francisco,

he left his mark on many productions, and made the company of the City on

the Bay his own.