|

Ross Finney, 90, Composer Of the Modern and Lyrical

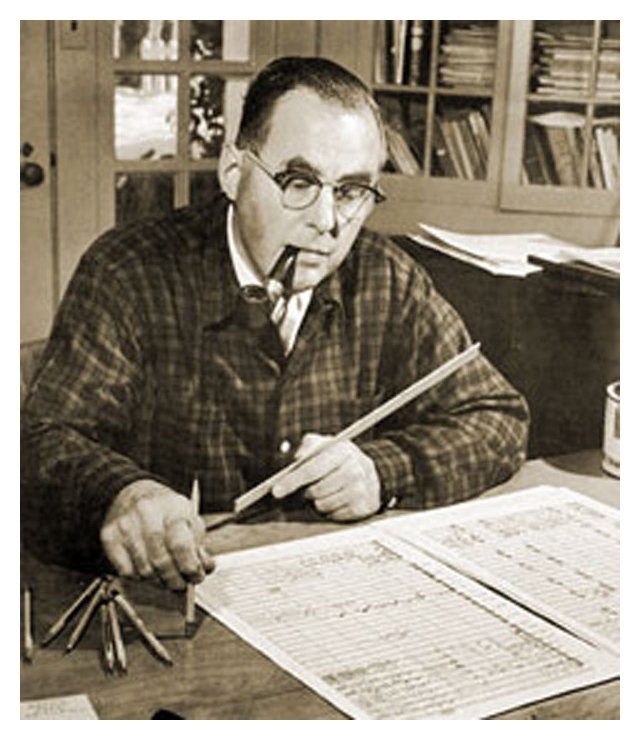

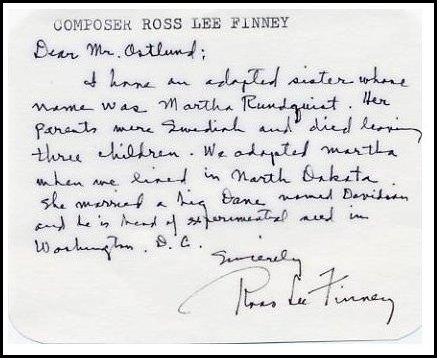

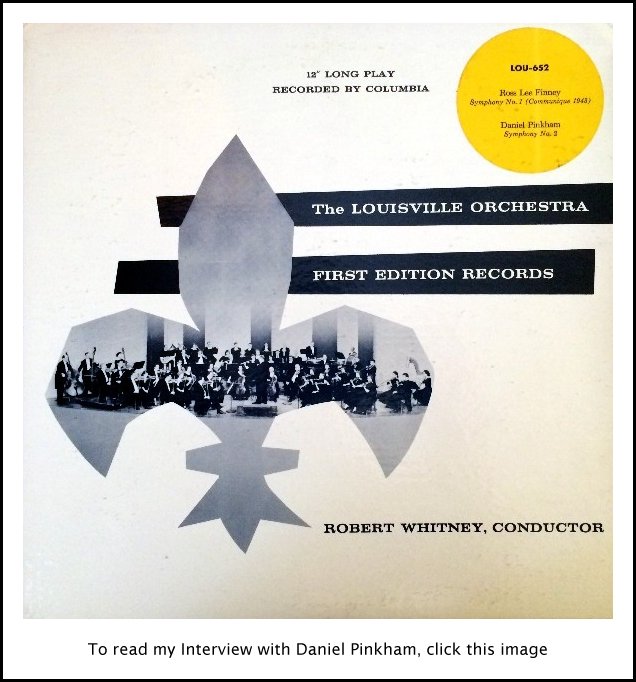

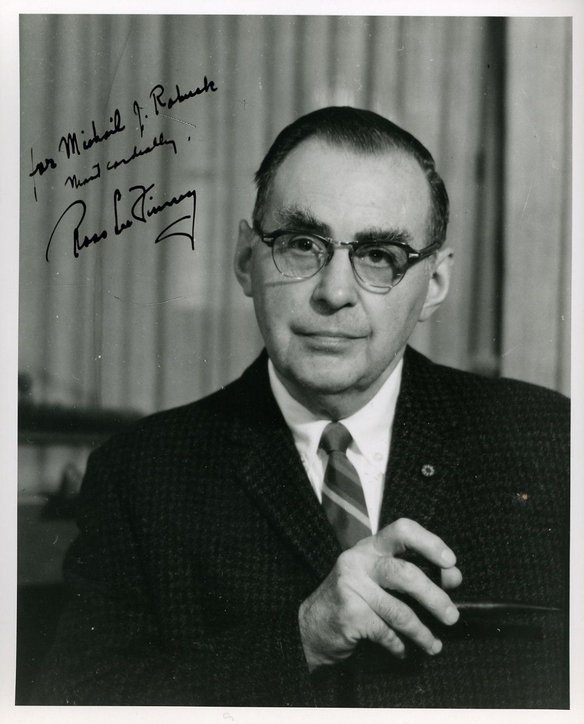

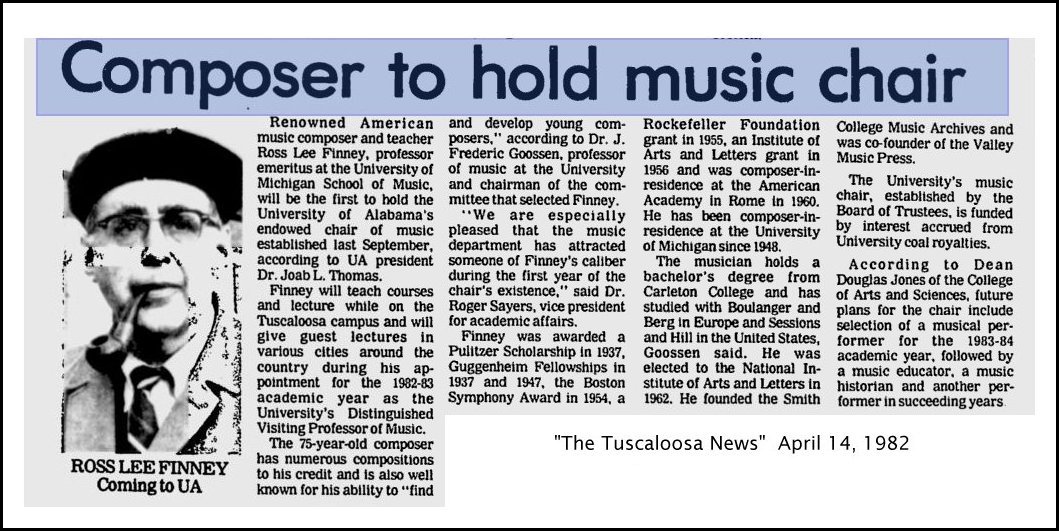

By ALLAN KOZINN Published: The New York Times, February 07, 1997 [Text only, with additions and corrections. Photos from other sources.] Ross Lee Finney, a composer and teacher who was fascinated with the role of memory in both the composition and the understanding of music, died on Tuesday at his home in Carmel, Calif. He was 90. Mr. Finney was a prolific composer whose style evolved considerably in a career lasting nearly seven decades. After studies with Nadia Boulanger in Paris in the late 1920's and Edward Burlingame Hill at Harvard in 1929, and private studies with Alban Berg and Roger Sessions in the 1930's, Mr. Finney composed works in which hints of American folk music rounded off the edges of an abstract international style. He received the 1937 Pulitzer Award for his "First String Quartet." Other awards followed, including two Guggenheim fellowships, the Boston Symphony Award, the Brandeis Medal, and election to both the National Institute of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In the early 1940's, the folk influence was ascendant as Mr. Finney, along with Copland, Barber, Siegmeister and other American composers, created a style that evoked everything from the Midwestern prairies to New England hymns. That style gave way to chromaticism in the late 40's and to a more rigorous 12-tone period that began about 1950. In his 12-tone works, though, he usually maintained connections to both tonality and the structural forms common to tonal music, a combination of influences he called his ''method of complementarity.'' Often, his 12-tone works had a lyricism that made them seem almost neo-Romantic. His interest in the tensions between competing compositional systems used in the same pieces was related to his interest in the relationship between music and memory. In some works -- ''Landscapes Remembered'' (1971), for example -- he toyed with listeners' memories by allowing themes based on folk songs and hymns to fade in and out of perspective. Mr. Finney was born on December 23, 1906, in Wells, Minn., and grew up in North Dakota and later in Minneapolis. He studied piano, cello and guitar and performed in a local orchestra, a trio and a jazz band during his teen-age years.

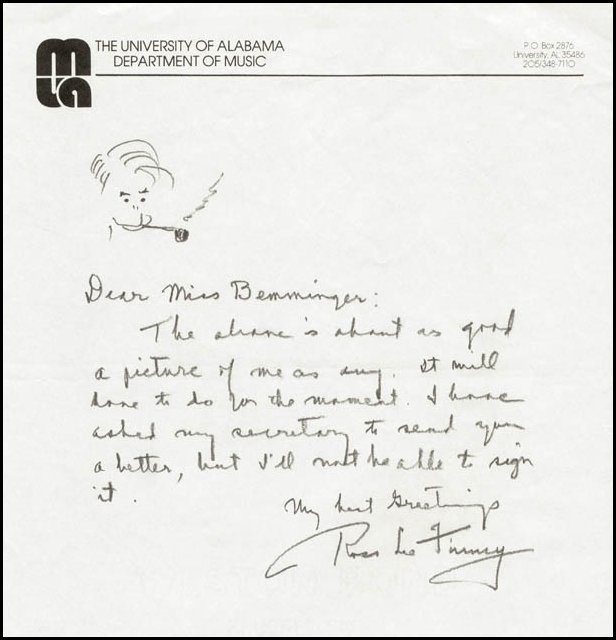

He began his composition studies when he was 12 and continued them at the University of Minnesota and Carleton College in Northfield, Minn. He also taught cello and music history at Carleton. After his return from Paris in 1928, he joined the faculty of Smith College in Northampton, Mass., where he started a series of scholarly publications of Baroque works. He also started the Valley Press, which published works by American composers. In the early 1940's, Mr. Finney taught at Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Mass., and at the Hartt School of Music in Hartford. During World War II, he served with the Office of Strategic Services and was awarded a Purple Heart. In 1949 he joined the faculty of the University of Michigan and remained there as a professor and composer in residence until 1974. His students included several prominent composers, among them Robert Ashley, William Albright, Leslie Bassett, George Crumb and Roger Reynolds. During the 1982-83 academic year, Finney was the Distinguished Visiting Professor of Music at the University of Alabama. [See the news item reproduced at the bottom of this webpage.]

Mr. Finney's works include eight string quartets; four symphonies; numerous chamber works and song cycles; two ballets, ''Heyoka'' (1981) and ''The Joshua Tree'' (1984), and two stage works, ''The Nun's Priest's Tale'' (1965), based on Chaucer, and ''Weep Torn Land'' (1984). There was also an unfinished opera, ''A Computer Marriage.'' A book of his essays, ''Thinking About Music: The Collected Writings of Ross Lee Finney,'' and an autobiography, ''Profile of a Lifetime,'' were both published in 1992. He is survived by two sons, Henry and Ross Jr. |

RLF: I do not know if this obsession with circles

has a deep philosophical root, but naturally there is. The circle is

a very interesting symbol in art. This interest in circles has been

taken over by my student, George Crumb. Probably

when they refer to my philosophical interest they are referring more to my

approach to serialization and twelve-tone technique. I have been very

much influenced by such physicists as Niels Bohr and Robert Oppenheimer in

the attitude or general idea that we cannot derive things from a single viewpoint.

Bohr speaks of this as complementarity. The Newton ideas are valid

for certain aspects of physical analysis, but the quantum theory has to be

used for others. In other words, my theory is that the large tonal

scope of music, the macrocosmic quality of music, falls back on the acoustical.

If you want you can use the word ‘tonal’.

I never relate ‘tonal’ to ‘triadic’

any more than to ‘modal’. I

certainly do not mean ‘tonality’

as we now apply it to what we call Classical compositions. Tonality

for me is the magnetism of pitch points in a work, so we write the large form

of the work in those terms. But the microcosmic events, the small elements,

are controlled by other series such as twelve-tone, triadic, or modal, or

what have you.

RLF: I do not know if this obsession with circles

has a deep philosophical root, but naturally there is. The circle is

a very interesting symbol in art. This interest in circles has been

taken over by my student, George Crumb. Probably

when they refer to my philosophical interest they are referring more to my

approach to serialization and twelve-tone technique. I have been very

much influenced by such physicists as Niels Bohr and Robert Oppenheimer in

the attitude or general idea that we cannot derive things from a single viewpoint.

Bohr speaks of this as complementarity. The Newton ideas are valid

for certain aspects of physical analysis, but the quantum theory has to be

used for others. In other words, my theory is that the large tonal

scope of music, the macrocosmic quality of music, falls back on the acoustical.

If you want you can use the word ‘tonal’.

I never relate ‘tonal’ to ‘triadic’

any more than to ‘modal’. I

certainly do not mean ‘tonality’

as we now apply it to what we call Classical compositions. Tonality

for me is the magnetism of pitch points in a work, so we write the large form

of the work in those terms. But the microcosmic events, the small elements,

are controlled by other series such as twelve-tone, triadic, or modal, or

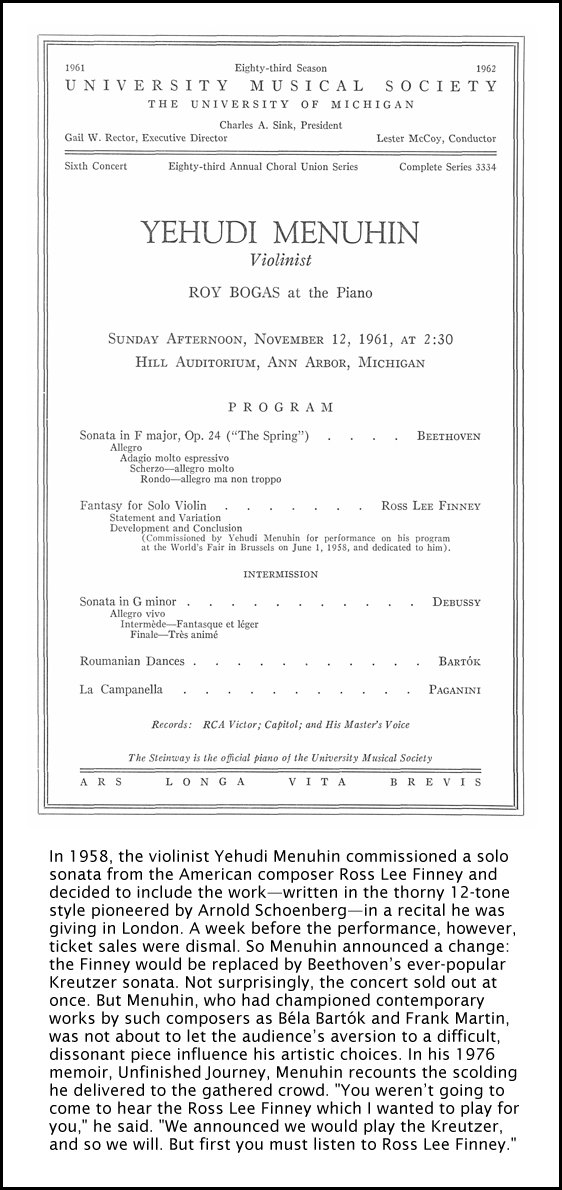

what have you. RLF: That varies. When Menuhin commissioned

my work for a violin work, it was obvious that I had to write that work for

solo violin. It was also obvious Menuhin doesn’t play to

audiences of 20 or 30 people. He plays to audiences of several

thousands. Therefore it had to be a work for violin that would project

in a large auditorium. So right off the bat, as a composer, I was up

against a very specific, pragmatic situation. So from that standpoint

I knew who I was writing it for. Now when it comes to an audience,

I am afraid that I don’t even think there is such a

thing as ‘an audience’.

There are just a lot of people that get together in a room, and these people

respond because they have ears. Therefore I have no way of knowing,

whether these people sitting together are feeling a piece of music in the

same way. Nobody knows. All you can say is they have ears.

Therefore the only contact that I have with the audience is the fact that

I too have ears. So what do I write for? I write for my ears.

I can hardly write for anybody else’s ears.

RLF: That varies. When Menuhin commissioned

my work for a violin work, it was obvious that I had to write that work for

solo violin. It was also obvious Menuhin doesn’t play to

audiences of 20 or 30 people. He plays to audiences of several

thousands. Therefore it had to be a work for violin that would project

in a large auditorium. So right off the bat, as a composer, I was up

against a very specific, pragmatic situation. So from that standpoint

I knew who I was writing it for. Now when it comes to an audience,

I am afraid that I don’t even think there is such a

thing as ‘an audience’.

There are just a lot of people that get together in a room, and these people

respond because they have ears. Therefore I have no way of knowing,

whether these people sitting together are feeling a piece of music in the

same way. Nobody knows. All you can say is they have ears.

Therefore the only contact that I have with the audience is the fact that

I too have ears. So what do I write for? I write for my ears.

I can hardly write for anybody else’s ears.The United States Information Agency (USIA) was established by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in August 1953 and was active until October 1, 1999. One way the USIA fulfilled its mission involved the identification, promotion, and financial support of young, virtuoso American performers as "ambassadors" of international understanding and goodwill. Following the success of a 1982 pilot program that sent pianist Robert Noland to tour France and Germany, USIA director Charles Z. Wick formally launched the Artistic Ambassador Program in April 1983 under the leadership of John Robilette, and named pianist Arthur Greene the second artistic ambassador. The program continued to expand rapidly, and by 1985, eleven pianists had traveled to thirty-eight countries, including the Soviet Union and China. By 1986 and 1987 respectively, the performance programs had also incorporated violin-piano duos and cello-piano duos. Touring efforts continued until the termination of the program in 1989. In addition to its support of performers, the program sought commissioned works from eminent American composers (listed below). This marked one of the first dedicated efforts by the federal government to commission musical works for the purpose of promoting American culture abroad. Between 1983 and 1987, a total of thirteen works were commissioned by the program. * *

* * *

USIA Artistic Ambassador Program musical commissions Published 1973-88. Written in English. About the Book..... This collection consists of works commissioned by the Artistic Ambassador Program and other materials related to the program. It includes holograph manuscripts and sketches, or both, for all thirteen commissioned pieces by the following composers: Ernst Bacon, Norman Dello Joio, Ross Lee Finney, Lukas Foss, Morton Gould, Lee Hoiby, Benjamin Lees, William Mayer, Robert Muczynski, George Perle, George Rochberg, Elie Siegmeister, and Leo Smit. Two additional pieces by Foss and Smit that were commissioned by the USIA before the establishment of the program are also included. In addition, the materials include correspondence, memoranda, performance reviews, brochures, press releases, clippings, biographical materials, and administrative documents. |

RLF: I learned a great deal. I was terribly

wet behind the ears when I went to work with Boulanger. I worked my

way to Europe by playing with a jazz orchestra, and she took me seriously.

She really taught me! People talk about her telling them that they’ve

got to study harmony and counter point, and so forth. Well, she didn’t

discourage that, but she didn’t spend the time doing that. She really

worked with me as a composer, and made me realize that the notes that I decided

to write were important. This ability that she had of taking somebody

from a culture that was very foreign to her and really helping them, was

quite remarkable! You’ve got to realize, too,

that in 1927 my peers there, the students that were working with her, also

had a big impact on me — people like Roy Harris and

Aaron Copland and Walter Piston, and many younger ones that you may not know

of. This group of talented young students had an enormous effect on

me, especially Copland, who made me less embarrassed by the fact that I had

grown up in North Dakota. There was something that Aaron had that was

quite remarkable in encouraging me. So while there are many qualities

that Nadia had that I am sure people have found objectionable, nevertheless

I’ve got to admit that I owe a great debt to her.

I later worked with Alban Berg and Roger Sessions.

RLF: I learned a great deal. I was terribly

wet behind the ears when I went to work with Boulanger. I worked my

way to Europe by playing with a jazz orchestra, and she took me seriously.

She really taught me! People talk about her telling them that they’ve

got to study harmony and counter point, and so forth. Well, she didn’t

discourage that, but she didn’t spend the time doing that. She really

worked with me as a composer, and made me realize that the notes that I decided

to write were important. This ability that she had of taking somebody

from a culture that was very foreign to her and really helping them, was

quite remarkable! You’ve got to realize, too,

that in 1927 my peers there, the students that were working with her, also

had a big impact on me — people like Roy Harris and

Aaron Copland and Walter Piston, and many younger ones that you may not know

of. This group of talented young students had an enormous effect on

me, especially Copland, who made me less embarrassed by the fact that I had

grown up in North Dakota. There was something that Aaron had that was

quite remarkable in encouraging me. So while there are many qualities

that Nadia had that I am sure people have found objectionable, nevertheless

I’ve got to admit that I owe a great debt to her.

I later worked with Alban Berg and Roger Sessions.| The ONCE Group was a collection of

musicians, visual artists, architects, and film-makers who wished to create

an environment in which artists could explore and share techniques and ideas

in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The group was responsible for hosting

the ONCE Festival of New Music in Ann Arbor, Michigan, between 1961 and 1966.

ONCE’s organizers were five composition students of the University of Michigan School of Music composition professor Ross Lee Finney and visiting professor of composition Roberto Gerhard (1896–1970): Robert Ashley, George Cacioppo, Gordon Mumma, Roger Reynolds, and Donald Scavarda. By 1957, all of these composers were residing in Ann Arbor and were becoming acquainted with each other, if they weren't already. "ONCE turned out to be a festival in

which we presented in the best way we possibly could with limited resources

both our own music and the music of others we thought was really important

to be heard. The people who were most interested were [the ONCE composers].

But it certainly was clear––we literally called it ONCE assuming that it

would not happen more than once––when there was such remarkable intensity

in those events, that there was something there that was more than just a

personal interest or need on our parts." —Roger Reynolds

ONCE is a name for a multitude of events that happened in many places and forms throughout the 1960s. What started as the ONCE Festival of Musical Premieres in February and March 1961 turned into the six-year-running ONCE Festival, with many derivatives including the ONCE Group (a theatrical ensemble), ONCE Friends, ONCE AGAIN, and the Ann Arbor Film Festival. Other festivals across America and North America, including New Dimensions in Music in Seattle, New Arts Workshop in Tuscan, Bang Bang Bang Festivals in Richmond, and Isaac Gallery Series in Toronto, modeled themselves after ONCE. |

BD: [Surprised] Oh!?!? [Laughs]

BD: [Surprised] Oh!?!? [Laughs]

This interview was recorded on the telephone on July 5, 1986.

Because the sound on the tape was poor, I spoke quotations from

the interview during programs on WNIB later that year and again in 1991 and

1996. The first portion of the interview was transcribed and published

in SONUS Magazine in the Spring of 2008. The rest was transcribed and

the entire interview was posted on this website in 2015.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.