A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

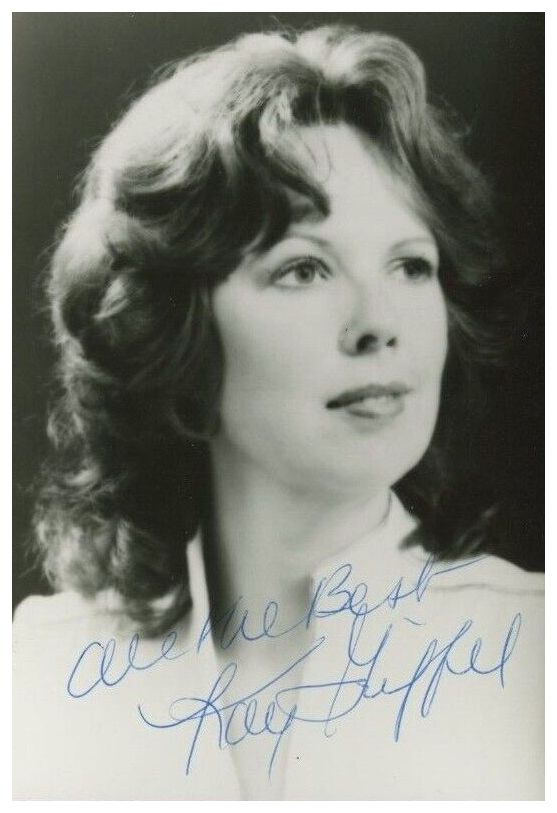

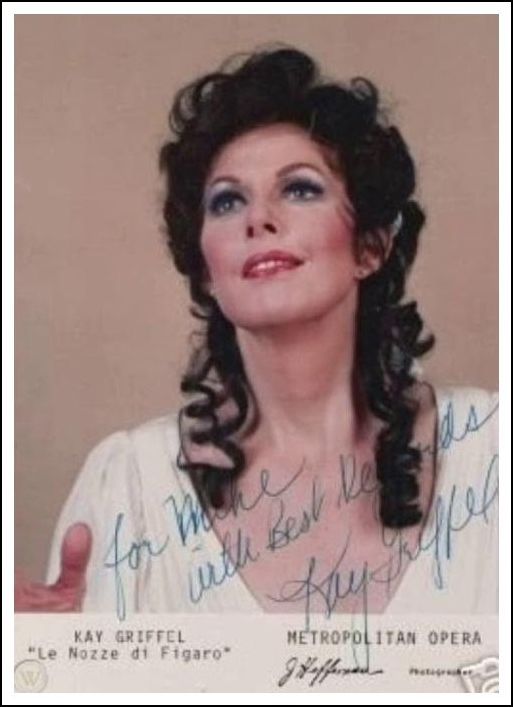

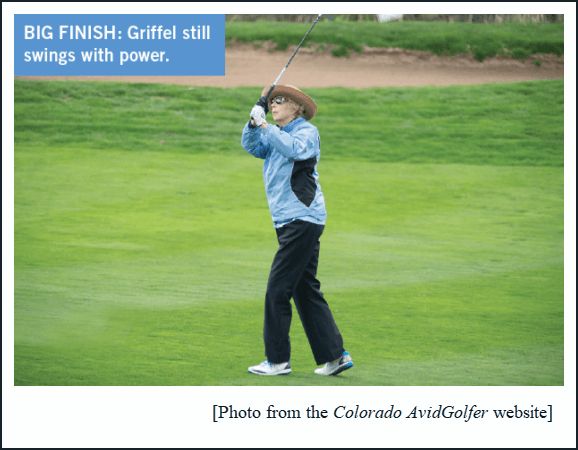

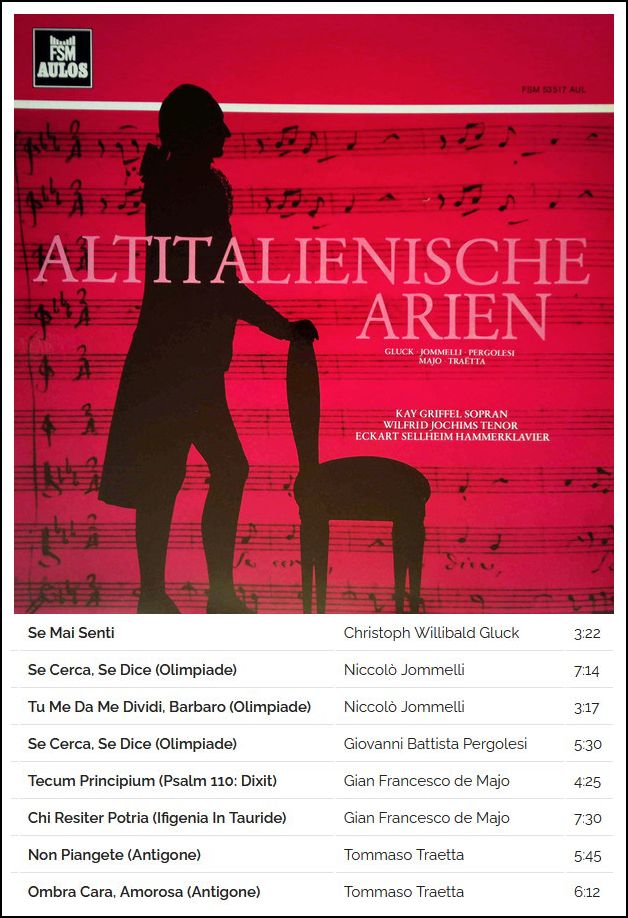

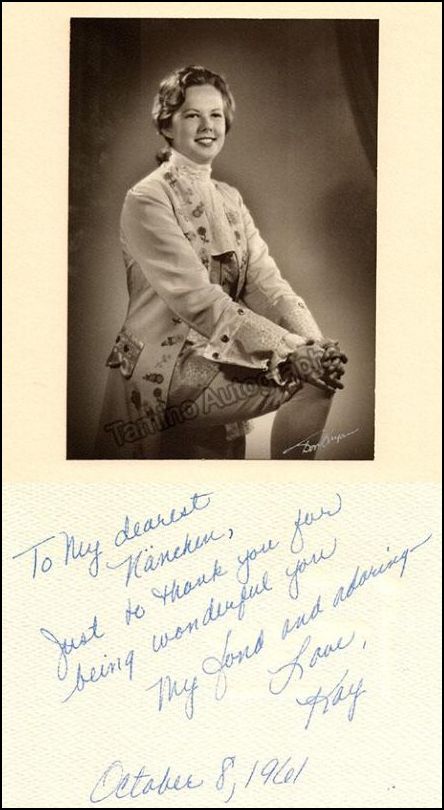

Kay Griffel (born December 26, 1940, in Eldora, Iowa) is an American operatic spinto soprano. After earning a Bachelor of Music from Northwestern University, she pursued further studies with Lotte Lehmann at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara. She received a Fulbright Scholarship and a Rockefeller Foundation Grant. In 1962 she won the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions. She also won a competition sponsored by the National Association of Teachers of Singing. In the mid 1960s she pursued graduate studies at the Musikhochschule Berlin. She also received further instruction from Nadia Boulanger at the Fontainebleau School, and Pierre Bernac in Paris. On November 4, 1960, Griffel made her stage debut at the Lyric Opera of Chicago as Mercédès in Bizet's Carmen with Jean Madeira in the title role, Renata Scotto as Micaëla, Giuseppe di Stefano as Don José, Robert Merrill as Escamillo, and Lovro von Matačić conducting. She also appeared there that season as the Shepherd Boy in Puccini's Tosca, Siegrune in Wagner's Die Walküre, the Little Savoyard in Giordano's Fedora, and Kate Pinkerton in Puccini's Madama Butterfly. In 1963 Griffel then moved to Berlin and was soon given several assignments

in the mezzo-soprano repertoire at the Deutsche Oper Berlin. She then became

a member of the Bremen Opera and the Mainz Opera. At the later opera house

she began to branch out into leading soprano roles. She continued to perform

on a regular basis at the opera houses in both Karlsruhe and Bremen until

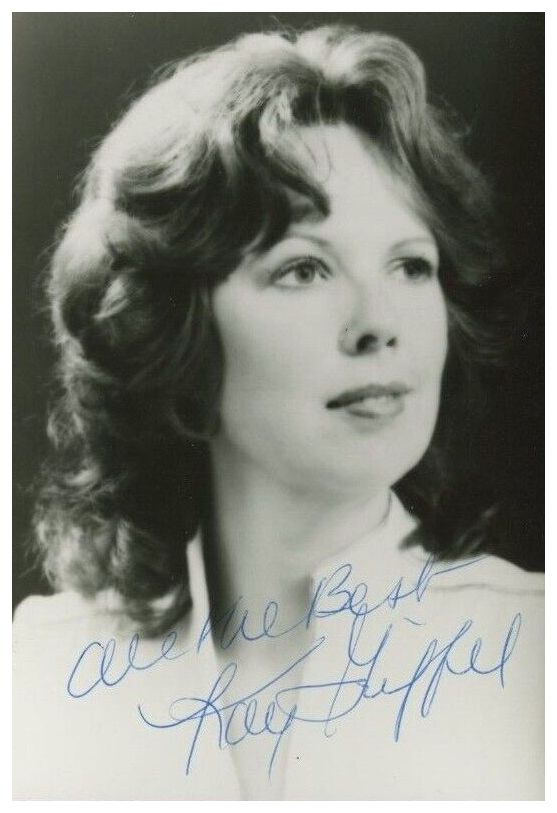

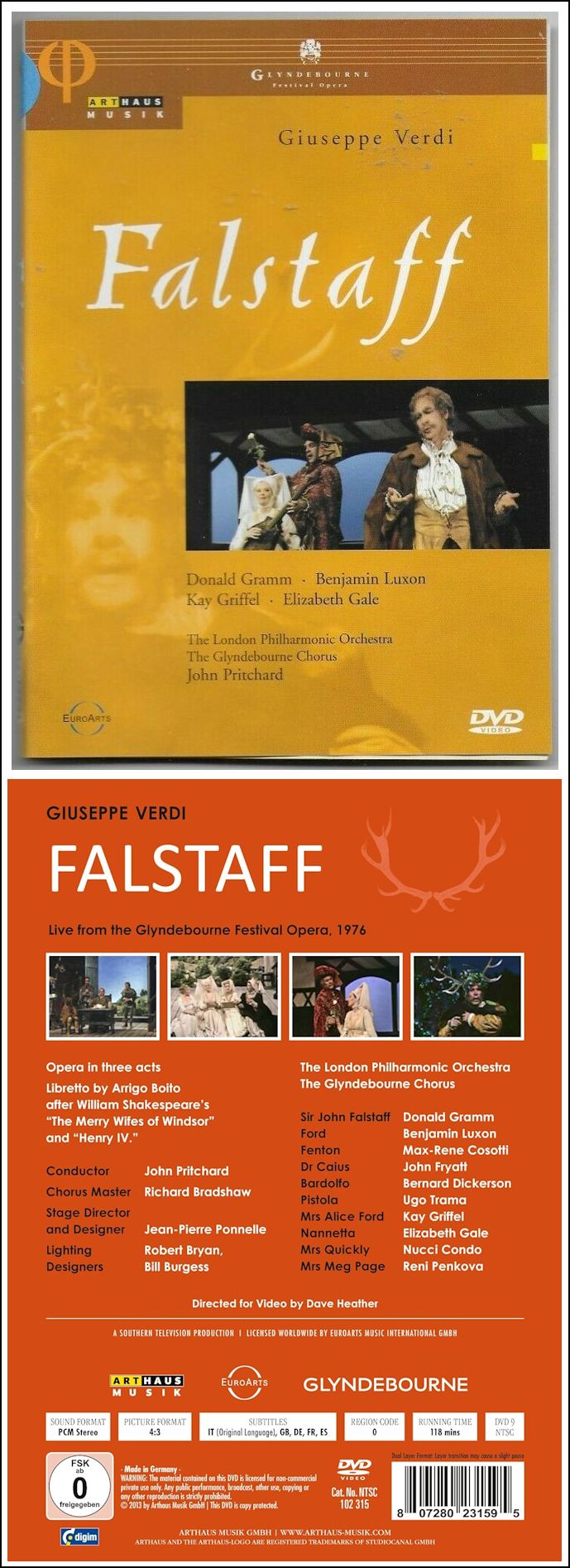

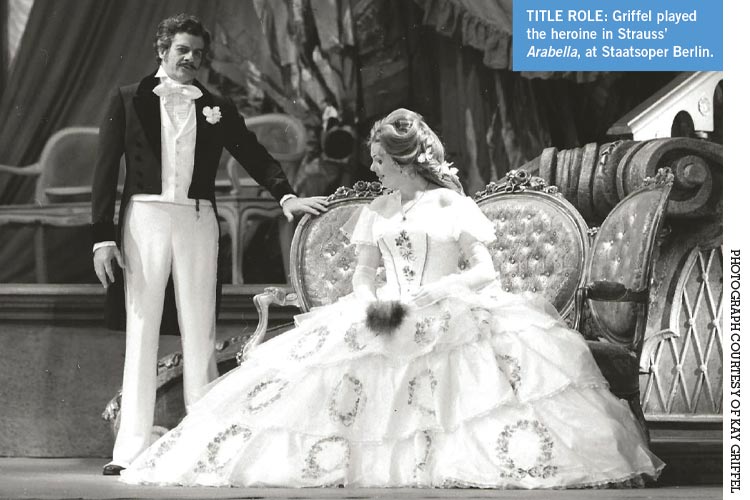

1973, when she became a resident member of the Staedtische Buehnen in Cologne. On August 20, 1973, Griffel made her debut at the Salzburg Festival as Sybille in the world premiere performance of Orff's De temporum fine comedia [recording shown above]. She was soon after engaged in leading roles at the Bavarian State Opera, the Deutsche Oper am Rhein, the Hamburg State Opera, the Liceu, and the Staatsoper Stuttgart. In 1976 she made her debut at the Glyndebourne Festival as Alice Ford in Verdi's Falstaff. In 1977 she toured with the Berlin State Opera to Japan, performing the roles of the Marschallin in Strauss' Der Rosenkavalier, Donna Elvira in Mozart's Don Giovanni, and the Countess Almaviva in Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro. In 1978 she portrayed Eva in Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg at the Teatro Nacional de São Carlos. On November 16, 1982, Griffel made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera as Elettra in Mozart's Idomeneo with Herman Malamood in the title role, Claudia Catania as Idamante, Ileana Cotrubas as Ilia, John Alexander as Arbace, and Jeffrey Tate conducting. She returned to the Met regularly over the next 7 years, portraying Countess Almaviva, Rosalinde in Die Fledermaus, Tatiana in Eugene Onegin, and the title role in Strauss' Arabella. Her final performance with the company was as Mozart's Elettra on March 3, 1989. During her career, Griffel also sang leading roles with the Frankfurt Opera, the Grand Théâtre de Bordeaux, the Houston Grand Opera, the Los Angeles Opera, La Monnaie, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, the Opera Company of Boston, Opera Ireland, the Royal Opera, London, the Staatsoper Hannover, the Teatro Comunale di Bologna, the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma, Theater Bonn, the Théâtre du Capitole, and the Welsh National Opera among others. Some of the other roles she performed on stage were Chrysothemis in Strauss' Elektra, Cleopatra in Handel's Giulio Cesare, Desdemona in Verdi's Otello, Elisabetta in Verdi's Don Carlos, Euridice in Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice, Fiordiligi in Mozart's Così fan tutte, Marguerite in Gounod's Faust, Micaëla in Bizet's Carmen, Mimì in Puccini's La bohème, Romilda in Handel's Serse, and the title roles in Strauss' Ariadne auf Naxos and Puccini's Manon Lescaut. Griffel is a former professor of voice at the University of Michigan,

and has taught masterclasses at several universities and conservatories

in the United States. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

|

The Great Caruso is a 1951 biographical film produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and starring Mario Lanza as famous operatic tenor Enrico Caruso. The movie was directed by Richard Thorpe and produced by Joe Pasternak with Jesse L. Lasky as associate producer. The screenplay, by Sonya Levien and William Ludwig, was suggested by the biography Enrico Caruso His Life and Death by Dorothy Caruso, the tenor's widow. The original music was composed and arranged by Johnny Green and the cinematography by Joseph Ruttenberg. Costume design was by Helen Rose and Gile Steele. The film is a highly fictionalized biography of the life of Caruso. [Vis-à-vis the movie poster shown below-right, see my interviews with Dorothy Kirsten, Jarmila Novotna, and Blanche Thebom.]

Nearly 40 years after its release, Caruso's son, Enrico Caruso Jr. reminisced that, "Vocally and musically The Great Caruso is a thrilling motion picture, and it has helped many young people discover opera and even become singers themselves." He added that, "I can think of no other tenor, before or since Mario Lanza, who could have risen with comparable success to the challenge of playing Caruso in a screen biography." The film has also been cited by tenors José Carreras, Plácido Domingo and Luciano Pavarotti as having been an inspiration for them when they were growing up and aspiring to become singers. The Great Caruso record album (though not an actual film soundtrack) was issued by RCA Victor on the LP, 45 and 78 RPM formats. The album featured eight popular tenor opera arias (four of which were heard in the film) sung by Lanza, accompanied by Constantine Callinicos conducting the RCA Victor Orchestra. The album sold 100,000 copies before the film premiered and later became the first operatic LP to sell one million copies. After its original 1951 release, the album remained continuously available on LP until the late 1980s and was reissued on compact disc by RCA Victor in 1989. |

| With heavy hearts, Des Moines Metro Opera

shares the loss of our beloved Founder and Artistic Director Emeritus,

Robert L. Larsen. He passed away peacefully in Indianola on Sunday, March

21, 2021. Our hearts go out to his family, friends and former students at

this time of immense sorrow. Visionary conductor and stage director Robert Larsen was born in Walnut, Iowa, in 1934. Against the backdrop of that rural Iowa community, he developed an unlikely interest in opera. Early in his career, he declined an offer from the Metropolitan Opera in order to remain in his home state to share his love for music and theatre with his fellow Iowans. Dr. Larsen believed that quality performances of great music should not exist exclusively in America’s largest cities, but could belong to everyone. With that in mind, in March of 1973 and with little time to spare, he selected opera titles, hired singers, formed a board of directors and raised $22,000 to launch Des Moines Metro Opera just a few months later on June 22, 1973. That first season, professional singers worked alongside his students to create something out of nothing via sheer determination and loyalty to their beloved leader. Larsen served as Conductor and Stage Director for every one of the nearly 120 productions for the Company’s first 38 seasons – an unparalleled accomplishment in American music. He worked and collaborated with more than a thousand singers, orchestra musicians, designers, technicians, and he motivated colleagues to reach the peak of their own capabilities. Today as the company he founded approaches its 50th Anniversary Season, he remained immensely proud of its next generation and the Company's continued success following his retirement in 2009.  His love of Iowa and great music was boundless. Nothing delighted

him more than great singing and marvelous young voices. His passion

for music-making inspired all those who had the opportunity to

work alongside him including artists, colleagues, students and members

of the community. He instilled in them the same awe and wonder that

surrounded his earliest memories of music and the joys of his life. The

strength of his vision to bring quality opera performances to Iowa brought

thousands of people to this magnificent art form, forever changing the

lives of so many. He will live on in our hearts forever.

His love of Iowa and great music was boundless. Nothing delighted

him more than great singing and marvelous young voices. His passion

for music-making inspired all those who had the opportunity to

work alongside him including artists, colleagues, students and members

of the community. He instilled in them the same awe and wonder that

surrounded his earliest memories of music and the joys of his life. The

strength of his vision to bring quality opera performances to Iowa brought

thousands of people to this magnificent art form, forever changing the

lives of so many. He will live on in our hearts forever.* * *

* *

Robert L. Larsen, Founder and Artistic Director Emeritus of Des Moines Metro Opera and Professor Emeritus of Music at Simpson College, has died. Dr. Larsen passed away peacefully in Indianola on Sunday, March 21, 2021. The announcement was made by DMMO General and Artistic Director Michael Egel. Known in music circles as the “Wizard of Iowa,” Dr. Larsen achieved widespread acclaim by almost single-handedly founding an annual summer opera festival amidst the Midwestern cornfields and guiding the organization to national prominence. Robert LeRoy Larsen was born into a farming family just outside the tiny town of Walnut, Iowa, on November 28, 1934. By age ten he was immersed in rigorous piano instruction and had become obsessed with the Saturday afternoon radio broadcasts from the Metropolitan Opera. The young musician entered Simpson College to study piano with Sven Lekberg. He subsequently attended the University of Michigan for graduate study, returned to join the music faculty at Simpson, and completed his doctorate in opera coaching and conducting at the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University. His piano studies were with Sven Lekberg, Joseph Brinkman, Rudolph Ganz and Walter Bricht. He worked as a conductor with Tibor Kozma and Wolfgang Vacano and with Boris Goldovsky in stage direction. Along the way, he received what might have been considered an irresistible offer to join the conducting staff of the Met. Larsen, however, had a different ambition – a resolve to bring professionally produced opera to a middle-American audience who had limited opportunity to experience the art form. Larsen’s first efforts resulted in Des Moines Civic Opera, which mounted two productions before he conceded the experience taught him “everything about how not to organize a company and board.” Then in 1973 he struck operatic gold with the formation of Des Moines Metro Opera with his co-founder and friend Douglas Duncan, utilizing the summer festival format and intimate performance space within Blank Performing Arts Center at Simpson College. Larsen perceptively realized he would need to strategically augment a repertory of accessible standards to cultivate developing audiences with more unusual fare that would potentially attract the attention of national audiences. His first season included Puccini’s La Rondine (a virtual rarity at that time), Benjamin Britten’s Albert Herring, and a double bill of Menotti’s The Medium paired with the North American premiere of Arthur Benjamin’s Prima Donna. His later seasons brought the world premiere of Lee Hoiby’s The Tempest and a rare American mounting of Weber’s Der Freischütz. The formula worked. Opera News magazine showed up that first year, followed by Opera Now and a host of major market newspapers, all of which helped to establish DMMO as one of America’s leading regional performing arts entities. The company’s subscription base quickly came to represent 40 states, most Iowa counties and several countries. Larsen mounted some 120 productions in 37 seasons, functioning as both conductor and stage director. This dual role resulted in an unusually cohesive fusion of musical and dramatic values. Although his command over a vast range of repertory was formidable, he displayed particular affinity for American works at a time when many companies were ignoring them. Floyd’s Of Mice and Men and Susannah as well as Blitzstein’s Regina, the major works of Menotti and three near-definitive mountings of Robert Ward’s The Crucible were highlights of his stewardship. He never shied from controversy and even presented nudity onstage in Richard Strauss’ Salome. A roguish humor evidenced itself on Independence Day performances when Larsen would conduct the national anthem using a blazing sparkler as a baton. Dr. Larsen served as Chair of the Department of Music at Simpson for 33 years, where he taught from 1957 until 2017. A consummate educator, he began an undergraduate opera program there, taught pianists, and lectured extensively on music history and theory, notably in a specialty course on Medieval and Renaissance literature. He coached and accompanied vocalists and founded a beloved chorus of Madrigal singers, whose concerts, European tours, and Christmas dinner performances became college and Midwestern traditions. Music lovers and artists frequently gathered at his Indianola home for DMMO and college events, and to marvel at his remarkable collection of European antiques (some of which found their way onto the DMMO stage as props) and a basement styled à la La Bohème’s Café Momus. Larsen was a remarkable solo and collaborative pianist, and he was well known for his collaborative performances with students, faculty and major performing artists including bass-baritone Simon Estes. Whether as professor or impresario, he nurtured the careers of countless musicians, many of whom enjoy international careers. He was selected as a recipient of the first Governor’s Award in Music in 1973 and the 1990 Iowa Arts Award presented by the Iowa Arts Council.

“Robert’s sense of awe and wonder for great works of music and art knew no bounds,” Michael Egel reflects. “His fierce passion for and devotion to sharing that love with colleagues, students and audiences through teaching and performing led thousands of people to this magnificent art form, forever changing the lives of so many. We are all forever in his debt. Nothing will ever quite be the same.” That passion remained with Larsen after his retirement and on to the end. During a celebratory gathering in DMMO’s lobby following the 2017 season, Larsen was seen to pull himself from his wheelchair to greet a young singer who had enjoyed a considerable success with the company that year. “Isn’t he a find?” Larsen enthused, his eyes sparkling once the singer had moved on. “Extraordinary voice. It’s so wonderful to encounter new voices like that.” Robert Larsen is survived by two nephews: Richard Healy (Maria Louisa Magcalas) of Seal Beach, CA, and Gary Healy of Oakland, CA; a great-nephew: Nathan Healy; as well as numerous friends in Indianola. He was preceded in death by his parents G. Dewey (1962) and Maine Larsen (1996), his sister Dorothy Healy (1972) and brother-in-law Early Healy (2015). Visitations will be held on Friday, March 26, from 3-8pm at the Overton Funeral Home in Indianola and on Saturday, March 27, from 9:00-10:30am at the First Presbyterian Church in Walnut, IA. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, no public graveside service is planned. When it is safe to do so, Des Moines Metro Opera will host a Memorial Concert for all to pay their respects and celebrate Larsen’s extraordinary life. Further details will be available at a later date. In lieu of flowers, memorial contributions may be directed to the Robert L. Larsen Scenic Fund at the Des Moines Metro Opera Foundation. == The text of the two items in this box are

an appreciation from the Des Moines Metro Opera, followed by the full obituary

(with photos added).

|

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on March 16, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1989. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.