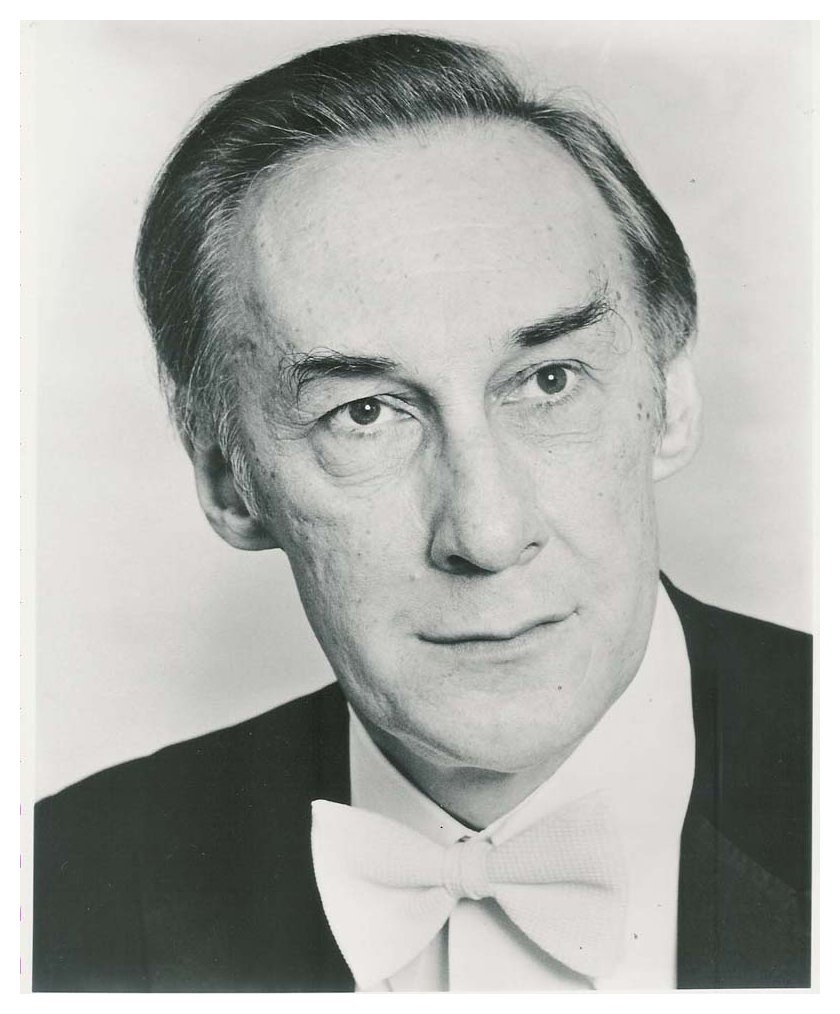

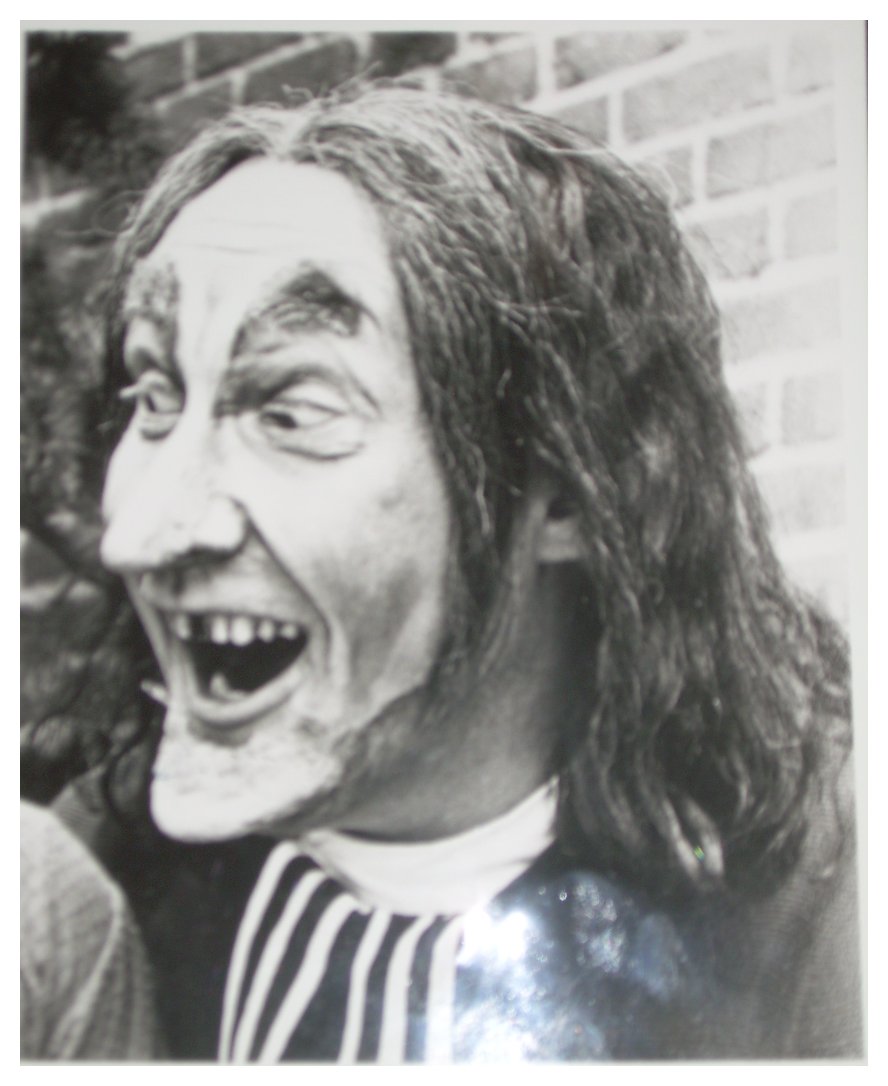

| Arnold Voketaitis was born on

May 11, 1930 in Connecticut. A bass-baritone of Lithuanian descent,

he is a graduate of Quinnipiac University. Before his singing career, Voketaitis

worked as a cars salesman, jazz trumpeter, and a radio announcer. He studied

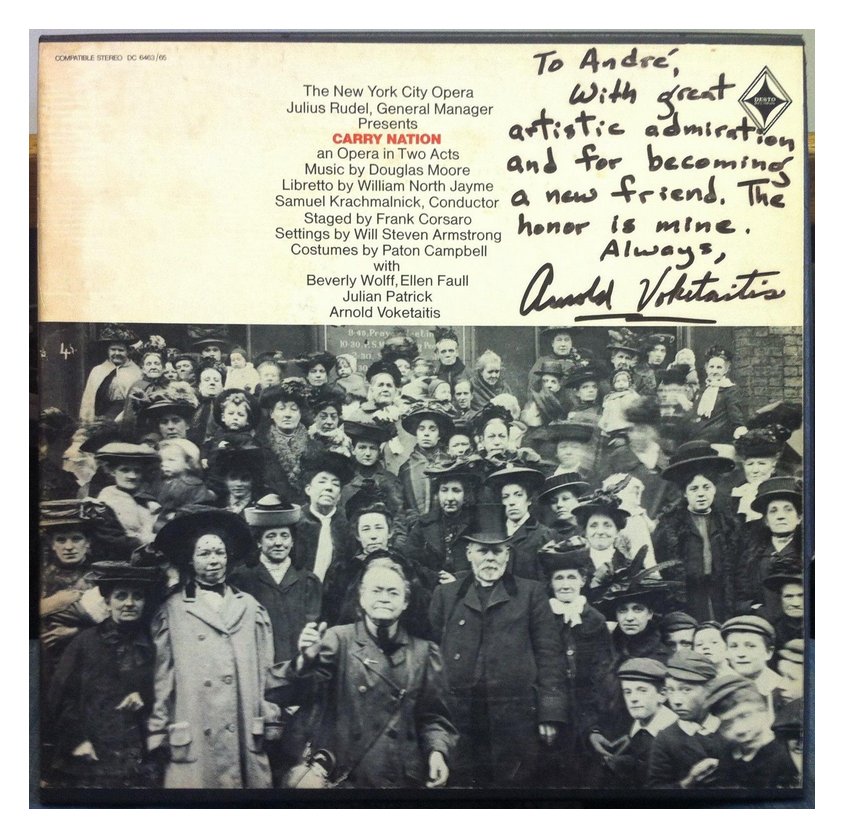

voice under Elda Ercole, Leila Edward and Kurt Saffir in New York City. Voketaitis began his singing career touring as soloist with the United States Army Band ("Pershing's Own") in 1956. With the Army Band, Voketaitis had the opportunity to perform for President Eisenhower at the White House. After winning several singing competitions in 1957 along with a Rockefeller Award, Voketaitis made his professional opera debut as Vanuzzi in Richard Strauss's Die schweigsame Frau at the New York City Opera (NYCO) in 1958. The following year he returned there to portray "The Stage Manager" in the world premiere of Hugo Weisgall's Six Characters in Search of an Author. He remained a regular performer with the NYCO up through 1981, singing such roles as Creon in Igor Stravinsky's Oedipus rex, Olin Blitch in Carlisle Floyd's Susannah, and Theseus in Benjamin Britten's A Midsummer Night's Dream among others. He notably sang the role of the Father in the NYC premiere of Douglas Moore’s Carry Nation in 1968. [Photo of recording below.]

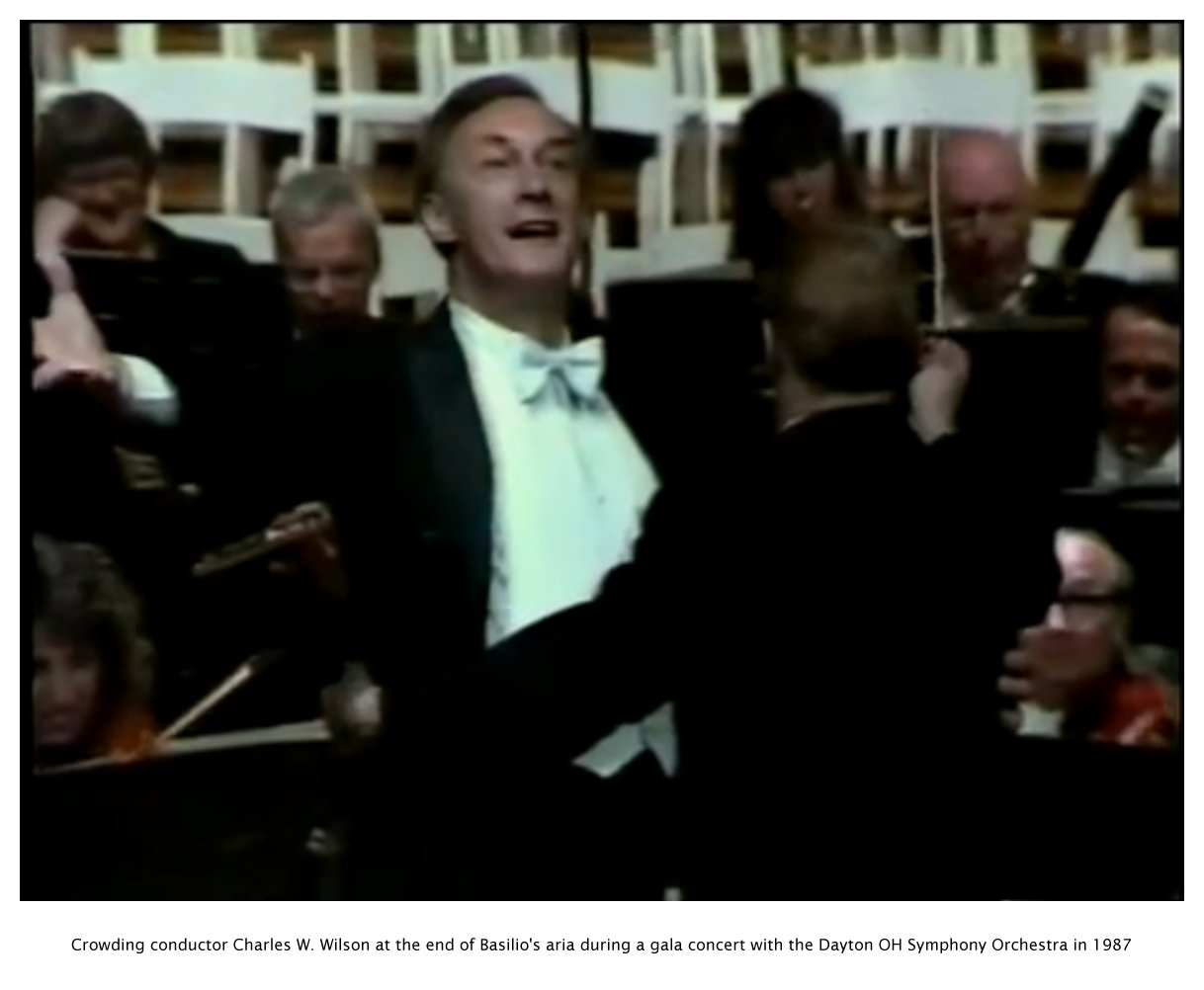

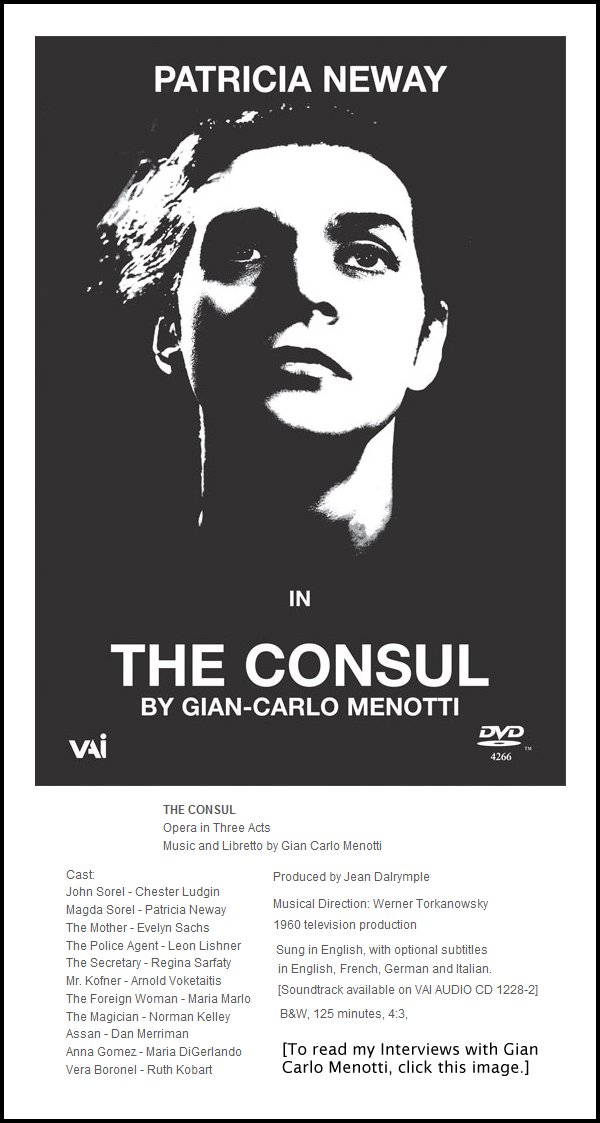

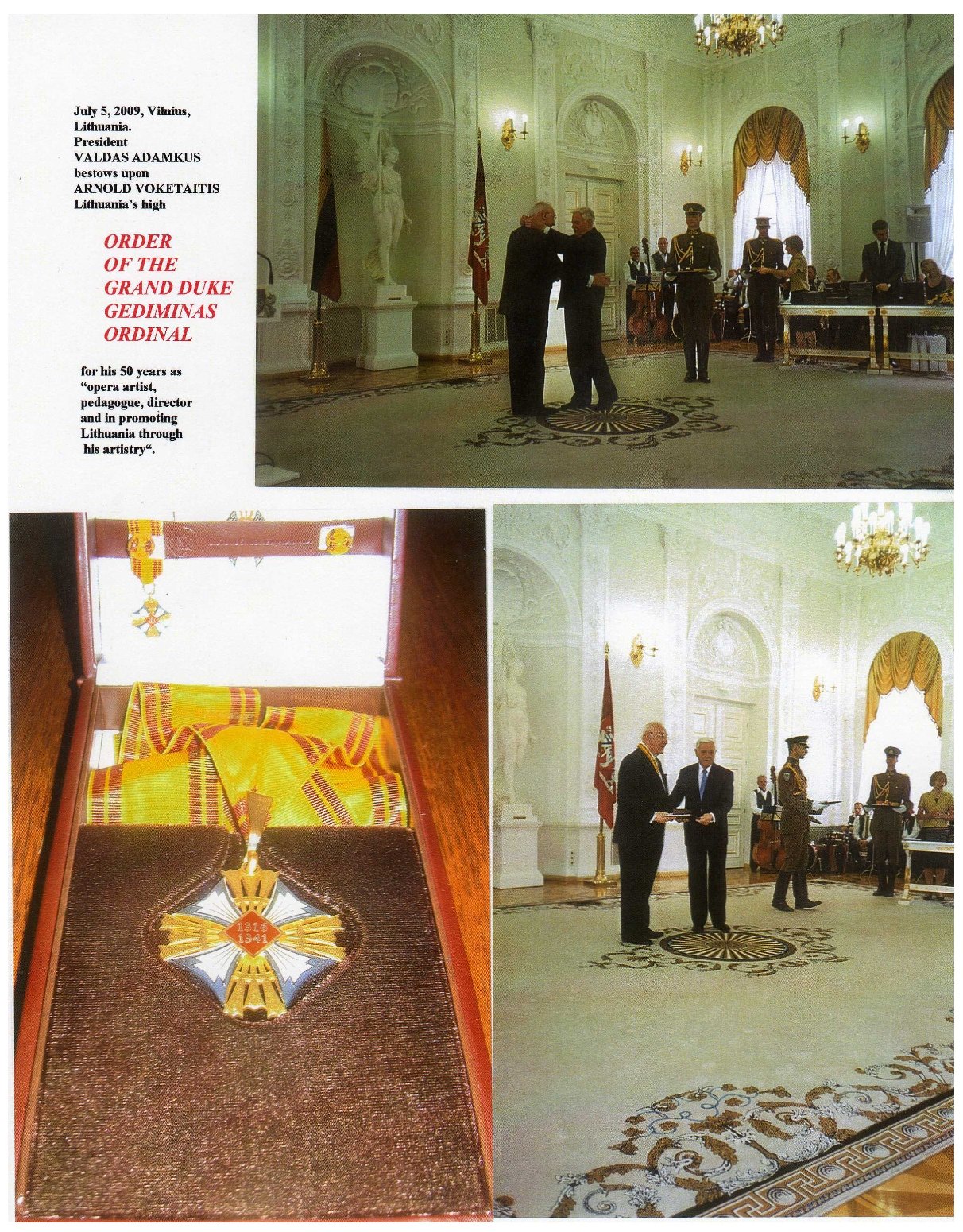

During the 1960s through the 1990s, he appeared as a guest artist at many important opera houses in North America, including the Houston Grand Opera, Milwaukee Opera Theatre, Opéra de Montréal, the Palacio de Bellas Artes, the Pittsburgh Opera, San Antonio Grand Opera Festival, and the Vancouver Opera among others. In 1964 he made his debut with the San Francisco Opera as Mephistophélès in Charles Gounod's Faust. In 1965 he sang Don Magnifico with the Metropolitan Opera National touring company. He sang regularly with the Lyric Opera of Chicago between 1968 and 1989, portraying such roles as Bonze (Le rossignol and Madama Butterfly), Zuniga, Loredano (I due Foscari), the Magistrate (Werther) and Mr. Ratcliffe for the American première of Billy Budd (1970). In 1980, at Mexico's Bellas Artes, he triumphed in the title role of Don Quichotte, repeating it in 1981 in Monterrey. In 1976 Voketaitis portrayed Rev. John Hale in Robert Ward’s The Crucible with the Florentine Opera. In 1989 he returned to Chicago as Abimelech in Camille Saint-Saëns's Samson et Dalila. The following year he sang Basilio in The Barber of Seville at the Miami Opera. He has also performed in concert the solo bass role in the Shostakovich 13th Symphony with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (1979), Minnesota (1980) and Dallas (1985) Symphonies, as well as the solo bass in Beethoven's 9th Symphony with the Pittsburgh Symphony. Other appearances include performing with the New York Philharmonic, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Cleveland Orchestra, Detroit Symphony Orchestra and the San Francisco Symphony among many others, under such conductors as Maxim Shostakovich, Leonard Bernstein, JoAnn Falletta, Leonard Slatkin, James Levine, Leopold Stokowski, and André Previn. Bernstein has said of Voketaitis, "From every point of view - vocal musicianship, intelligence, personal qualities - he is certainly a musical asset." Voketaitis's career has been mostly within North America. Aside from his many Mexico appearances, he has made a few other international appearances, including performing at the Liceu in Spain, the Teatro Nacional de Costa Rica, and the Teresa Carreño Cultural Complex in Venezuela. He has also made several recordings for television and CD, six of which have garnered Grammy Award nominations. He was notably awarded the Man of the Year Award from the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture, the Distinguished Alumni Medal from his alma mater (Quinnipiac University), as well as a Rockefeller Award. In 2009 he was awarded the Commander's Cross of the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas, Lithuania's high cultural medal, in honour of his artistic achievement and support of Lithuanian culture. In academia, he was Visiting Scholar/Artist-in-Residence for Opera and Voice at Auburn University in Alabama, Director of Opera at DePaul University in Chicago, artist faculty at Brevard Music Center, and guest lecturer at Northwestern University. -- Names which are links throughout

this webpage refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD

|

As I was setting up to record our conversation, Voketaitis mused on his

own radio career . . . . . . .

As I was setting up to record our conversation, Voketaitis mused on his

own radio career . . . . . . .

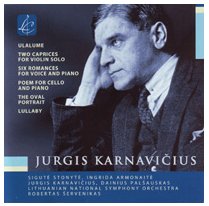

Jurgis Karnavičius (23 April 1884

– 22 December 1941) was a Lithuanian composer of classical music and a forerunner

of the development of Lithuanian operatic works. Karnavičius' son,

also named Jurgis Karnavičius (1912–2001), was a pianist and the long-time

rector of the Lithuanian Academy of Music. His grandson, Jurgis Karnavičius

(born 1957), is a concert pianist. Karnavičius was born in Kaunas, Lithuania, which at the time was a part

of the Russian Empire. After completing his basic education in his homeland,

he began the study of Law in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Karnavičius was born in Kaunas, Lithuania, which at the time was a part

of the Russian Empire. After completing his basic education in his homeland,

he began the study of Law in St. Petersburg, Russia.Music had always been his first love, and he began to simultaneously study music theory and composition, and this passion soon superseded his pursuit of a career in the legal profession. His primary instrument was the viola. Eventually he became a professor at the Conservatory of Music in the now renamed city of Leningrad. During this period he began experimenting with his own theories of musical composition and began writing his own works. In 1927, Karnavičius returned to Lithuania, which had only regained its independence as a sovereign nation less than ten years earlier. In addition to teaching at the Conservatory of Music in Kaunas, he opted to play the viola with the orchestra of the State Opera for a number of years. Having a personal desire write a new opera himself, and under the influence of the renewed national pride released by Lithuania's regaining its independence, Karnavičius began to write his first opera, Gražina, which premiered on February 16, 1933. It had incorporated more than forty melodies borrowed from Lithuanian folk songs, and was a popularly acclaimed success. It is considered among the first of the "Lithuanian National Operas." This was followed in 1937 by the opera Radvila Perkūnas, which was about the Lithuanian nobleman, Krzysztof Mikołaj Radziwiłł. |

Jūratė ir Kastytis was composed in the

last years of the composer's life, when he was almost destitute and suffering

from Parkinson's disease. Based on the ancient Lithuanian legend of the love

of a sea sprite for a mortal on the shores of the Baltic, this opera is

related to musical settings of the Lorelei and Undine myths — myths which

have much in common with that used as the basis for this opera. It is within

this context that I will discuss what has become one of the most influential

Lithuanian operas of the century. Although Kazimieras Viktoras Banaitis (1896-1963) composed in different

styles and genres, he is now known principally for the composition of this

opera. He began his musical studies at a private school of music in Kaunas,

1911-14. From 1922-28 he studied composition, piano, and musical pedagogy

at the Conservatory of Leipzig, where he studied, among others, with the

important German composer Sigfried Karg-Elert. After his studies in Germany,

he returned to Lithuania, where he was the director of the Kaunas Conservatory

from 1937-44. Because of the Soviet occupation, he left for Germany in 1944

and then went to the United States in 1949, where he spent the rest of his

life. He lived in Brooklyn, eking out a precarious existence giving private

lessons and working at minor musical positions.

Although Kazimieras Viktoras Banaitis (1896-1963) composed in different

styles and genres, he is now known principally for the composition of this

opera. He began his musical studies at a private school of music in Kaunas,

1911-14. From 1922-28 he studied composition, piano, and musical pedagogy

at the Conservatory of Leipzig, where he studied, among others, with the

important German composer Sigfried Karg-Elert. After his studies in Germany,

he returned to Lithuania, where he was the director of the Kaunas Conservatory

from 1937-44. Because of the Soviet occupation, he left for Germany in 1944

and then went to the United States in 1949, where he spent the rest of his

life. He lived in Brooklyn, eking out a precarious existence giving private

lessons and working at minor musical positions.His music received little attention during his lifetime, even from the large Lithuanian communities living in the United States. Banaitis was not a promoter of his works, preferring to think of composition as a pure task separate from practical affairs. In general, his music is rather conservative, with a clear emphasis on the folkloric. Modality, altered scales and chords — probably an influence from the Impressionists — and quintal harmonies prevail. He wrote a large number of choral arrangements of Lithuanian folk songs as well as chamber compositions. Jūratė ir Kastytis, the work Banaitis considered his masterpiece, is on a larger scale than his other compositions and more fully explores various contemporary devices. It was completed in 1955, though Banaitis spent the next five years refining it. In 1960 it was presented to a special committee who were charged with the publication and performance of this opera. It was premiered by the Lithuanian Opera Company of Chicago on April 29, 1972. -- From an article by Enrique

Alberto Arias, published in Litusnus,

the Lithuanian Quarterly of Journal of Arts and Sciences, Winter, 1966

(Text only - photo added from another source) |

| By Lesley Valdes, Inquirer Music Critic Posted: August 04, 1989 Yuri Temirkanov led the Philadelphia Orchestra in the final concert of the Mann Music Center's season last night with an aplomb that was roundly appreciated by a better-than-usual crowd at the open-air arena. The program, a good and well-executed one, was an audience pleaser, too: Stravinsky's Suite from L'Oiseau de feu (1919 version) and Prokofiev's Ivan the Terrible, Op. 116. Ivan, composed during the war years, 1942-45, to accompany the Sergei Eisenstein film, was heard in its oratorio arrangement by Abram Stasevich. Stasevich conducted the original film production. (...) Among the soloists, mezzo-soprano Claudine Carlson, last heard at the Academy of Music in Berlioz's Damnation of Faust, made a distinctive contribution with her potent and dark-hued voice. Bass-baritone Arnold Voketaitis (in the roles of Ivan, the simpleton and narrator) also held the attention remarkably well, particularly in the sung-speech of the English narration. Voketaitis, who according to program notes began his musical life as a trumpeter, has that instrument's sense of projection; further, he understands the spoken word's need for pauses, tension and tonal variety as well or better than many actors. |

AV: We all like a quick-fix because the advanced

artist doesn’t want to start all over again. In some cases you have

to if there are certain problems within the voice. If the voice is

breaking you have to work on a stronger support aspect, but a lot of my book

is derived from positioning and developing a core. It incorporates what

I have observed while sharing the stage with many, many great artists.

It shows the basic element that makes them successful, and what their technique

has given as far as longevity is concerned.

AV: We all like a quick-fix because the advanced

artist doesn’t want to start all over again. In some cases you have

to if there are certain problems within the voice. If the voice is

breaking you have to work on a stronger support aspect, but a lot of my book

is derived from positioning and developing a core. It incorporates what

I have observed while sharing the stage with many, many great artists.

It shows the basic element that makes them successful, and what their technique

has given as far as longevity is concerned.

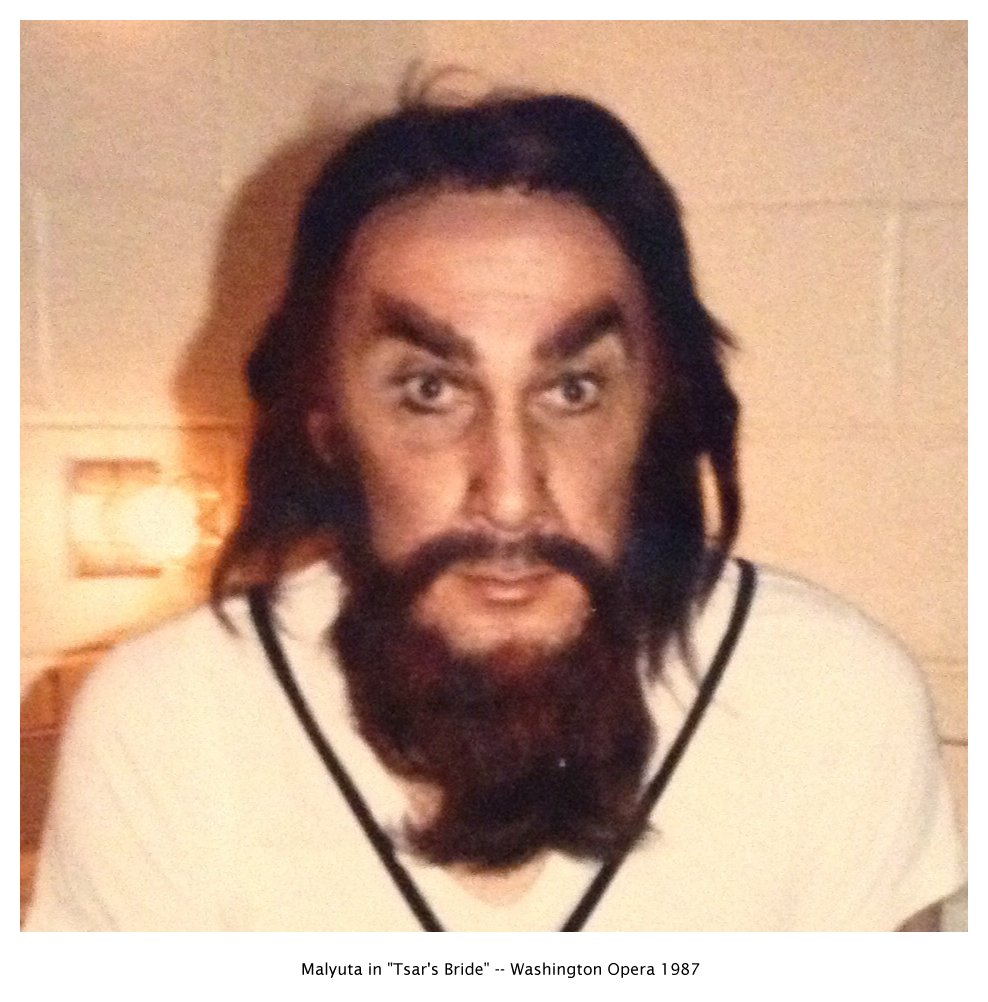

Arnold Voketaitis at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1966 - Magic Flute (Priest) with Häfliger, Watson, Kunz, Mesplé, Ridderbusch; Jochum, Graf Traviata (Dr. Grenvil) with Rinaldi/Maliponte, Kraus, Bruscantini, Zilio; Rossi, Hall 1968 [Opening Night] - Salome (Nazarene) with Weathers, Varnay, Hopf, Nienstedt, Theyard, Charlston; Bartoletti, Puecher Tosca (Sacristan) with Stella, Cioni, Guelfi, Van Ginkel, Lorenzi; Bartoletti, Bolognini Rossignol (The Bonze) with Eda-Pierre, Garaventa, Washington, Dominguez; Fournet, Novaro 1970 [Opening Night] - Rosenkavalier (Notary & Police Commissioner) with Ludwig, Minton, Berry, Brooks, Gutstein, Andreolli, Zilio, Garaventa; Dohnányi, Neugebauer, Schneider-Siemssen Billy Budd (Lt. Ratcliffe) with Uppman, Lewis, Evans; Bartoletti, Anderson, Piper Madama Butterfly (Bonze) with Amedeo, Tagliavini, Trimarchi, Krebill, Andreolli; Quadri, Aoyama, Lee 1972 [Opening Nightr] - Due Foscari (Loredano) with Ricciarelli, Tagliavini, Cappuccili; Bartoletti, De Lullo, Pizzi Traviata (Dr. Grenvol) with Casapietra, Merighi/Tagliavini/Ochman, Bordoni, Zilio; Arena, De Lullo, Pizzi Ballo in Maschera (Tom) with Arroyo, Tagliavini, Milnes, Koszut, Baldani; Dohnányi, Gobbi, Darling Pelléas et Mélisande (Physician) with Pilou, Stilwell, Petri, Ariè, Taillon, Zilio; Fournet, Deiber, Heeley 1973 - Carmen (Zuniga) with Cortez, King, Saccomani, Krilovici/Wells; López-Cobos, Novaro, Zuffi Rosenkavalier (Notary & Police Commissioner) with Ludwig/Dernesch, Berthold, Sotin, Blegen, Gutstein, Andreolli, Zilio, Merighi, Gordon; Leitner, Neugebauer, Schneider-Siemssen 1975 - Traviata (Dr. Grenvil) with Cotrubas, Kraus, Cappuccilli, Zilio; Bartoletti, De Lullo, Pizzi Marriage of Figaro (Bartolo) with Price, Malfitano, Dean, Stewart, Ewing, Begg, Andreolli; Pritchard, Ponnelle Fidelio (Don Fernando) with Jones/Wagemann, Vickers, Berry, Wise, Crass, Sherman; Ahronovich, Anderson 1976 [Opening Night] - Tales of Hoffmann (Crespel) with Domingo/Johns, Welting, Cortez, Eda-Pierre, Mittelmann, Zilio, Anddreolli, Kuhlmann; Bartoletti, Puecher, Frigerio Ballo in Maschera (Tom) with Ricciarelli, Carrereas, Bruson, Wise, Wolff; López-Cobos, Gobbi, Darling 1977- Peter Grimes (Swallow) with Vickers, Kubiak, Meredith/Evans, Bainbridge, June Anderson (2nd Niece); Bartoletti, Evans, Toms 1978 [Opening Night] Fanciulla del West (Ashby) with Neblett, Cossutta, Mastromei, Andreolli, Kuhlmann; Bartoletti, Prince, Lee Werther (Bailiff) with Minton, Kraus, Nolen; Giovaninetti, Samaritani 1979 - Andrea Chénier (Mathieu) with Marton, Domingo, Bruson, Graham/White, Curry/Graham, Kuhlmann, Gordon; Bartoletti, Gobbi, Samaitani 1980 - Ballo in Maschera (Count Horn [Tom]) with Scotto, Pavarotti, Nucci, Battle, Payne/Dunn; Pritchard, Frisell, Conklin, Tallchief Italian Earthquake Relief Fund Concert with (among others) Buchanan, Howells, Macurdy, Tomowa-Sintow, Troyanos, Winkler 1983 - Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk (Old Convict) with Zschau, Trussel, Negrini; Bartoletti, Ciulei 1984 - Frau ohne Schatten (One-armed Man) with Marton, Johns, Zschau, Nimsgern, Dunn, Devlin, Doss; Janowski, Corsaro, Chase 1989-90 - Rosenkavalier (Police Commissioner) with Tomowa-Sintow, von Otter, Moll, Battle, Patrick, Andreolli, Kraft, Welch; Kout, Decker, Schneider-Siemssen Samson et Dalila (Abimélech) with Domingo, Baltsa, Fondary; Bartoletti, Joël, Schmidt, Schuler, Tallchief At the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

|

© 1986 & 1997 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in Chicago on February 17, 1986 and May 5, 1997. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1986, 1993 and 2000. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at the beginning of 2015. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.