|

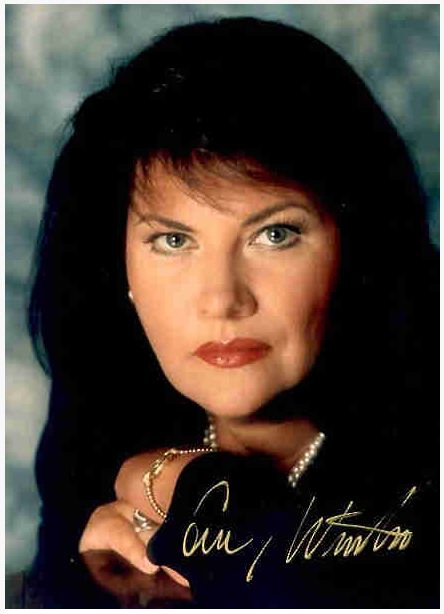

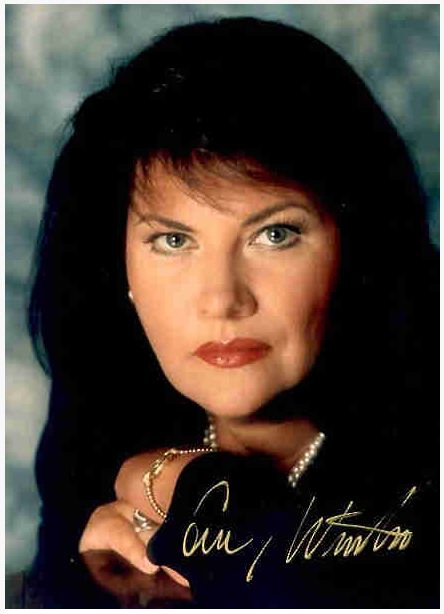

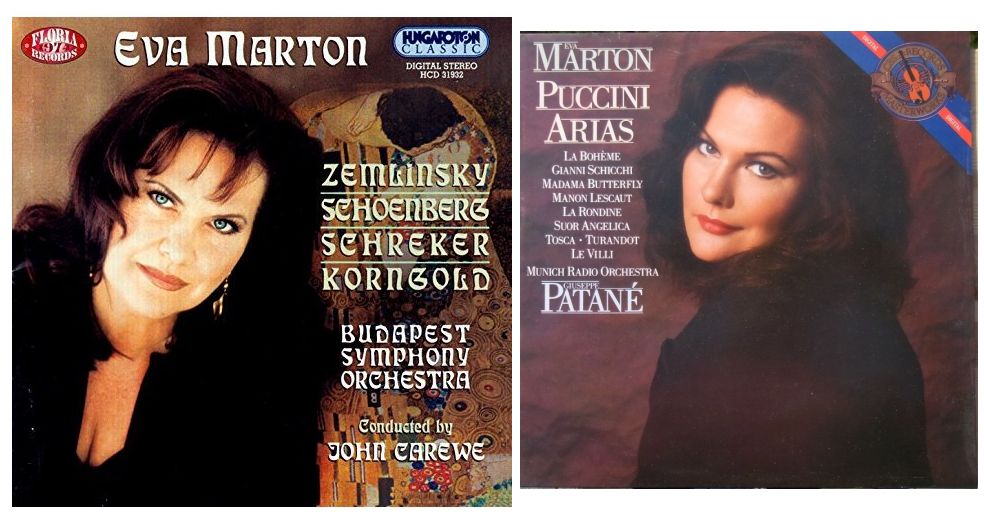

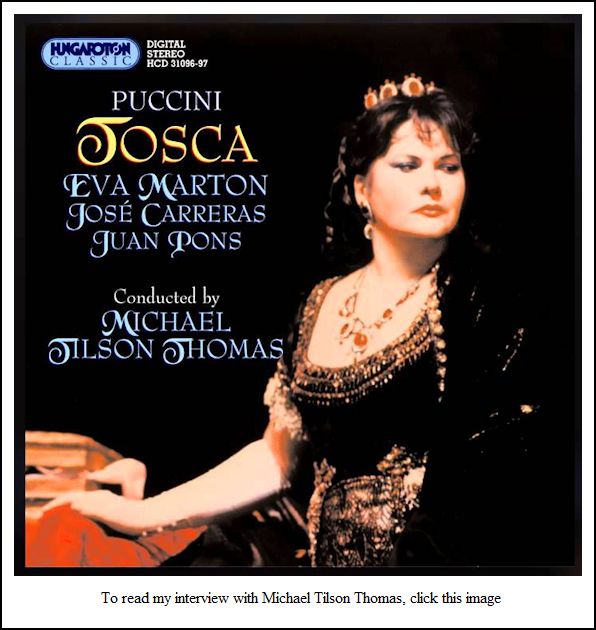

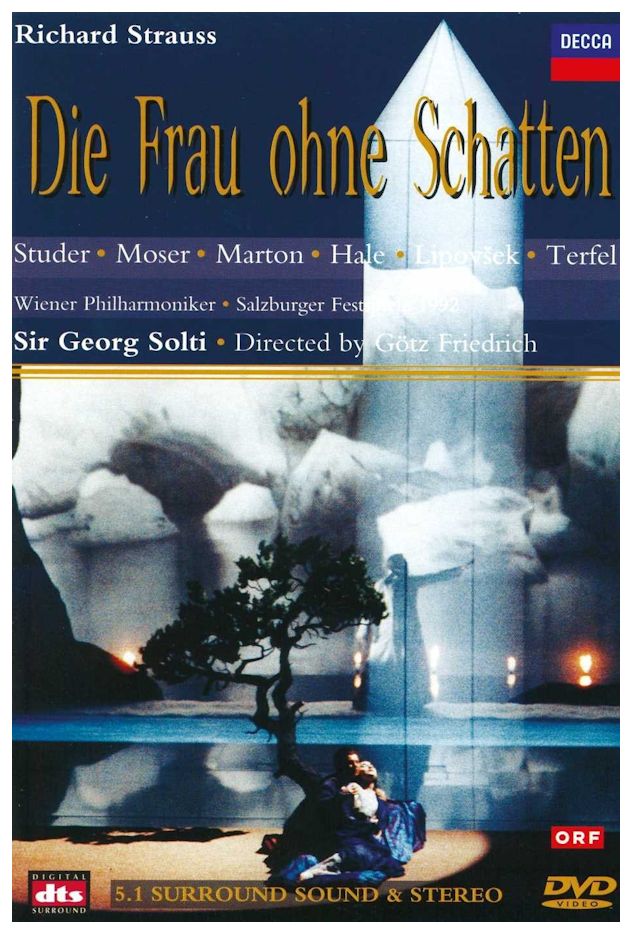

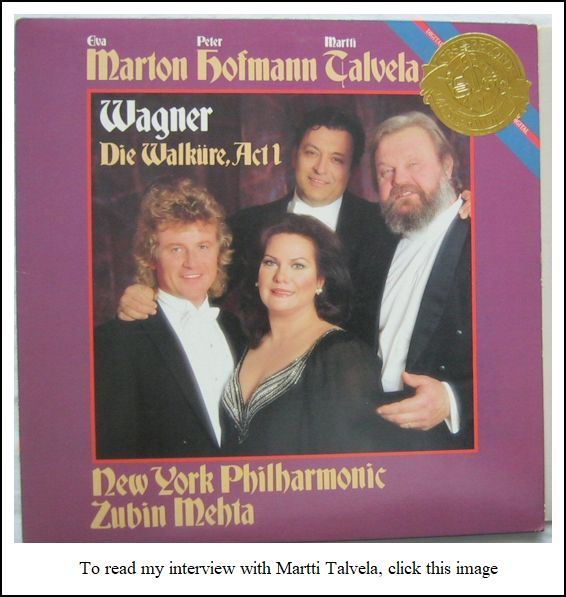

Eva Marton (born in Budapest June 18, 1943) is a Hungarian dramatic soprano, particularly known for her operatic portrayals of Puccini's Turandot and Tosca, and Wagnerian roles. She studied voice at the Franz Liszt Academy. She made her professional debut as Kate Pinkerton in Puccini's Madama Butterfly at Hungary's Margaret Island summer festival. At the Hungarian State Opera, she made her debut as Queen of Shemaka in Rimsky-Korsakov's The Golden Cockerel in 1968. In 1972, she was invited by Christoph von Dohnányi to make her debut as the Countess in The Marriage of Figaro at the Frankfurt Opera. That same year, she sang Matilde in Rossini's William Tell in Florence, conducted by Riccardo Muti. She also returned to Budapest to sing Odabella in Verdi's Attila. In 1973, Marton made her debut at the Vienna State Opera in Puccini's Tosca. In 1977, she sang at the Hamburg State Opera, in the role of the Empress in Strauss's Die Frau ohne Schatten, and made her San Francisco Opera debut in the title role of Verdi's Aïda. In 1978, Marton made her debut at La Scala in Milan as Leonora in Verdi's Il trovatore. She debuted at the Lyric Opera of Chicago in 1979 as Maddalena in Giordano's Andrea Chénier. In 1981, she performed at the Munich Opera Festival in the title role of Die ägyptische Helena by Strauss, Wolfgang Sawallisch conducting. She sang the role of Leonore in Beethoven's Fidelio in 1982 and 1983, both performances conducted by Lorin Maazel. In 1976, she made her Metropolitan Opera debut in New York in the role of Eva in Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. At the Bayreuth Festival she sang both Elisabeth and Venus in Tannhäuser in 1977-1978. Marton later became a frequent interpreter of the role of Brünnhilde in Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen. She performed in the complete Zubin Mehta-led Ring cycle at the Lyric Opera of Chicago in 1996. In 1998, she appeared in a new production of Lohengrin at the Hamburg State Opera, portraying Ortrud. Marton first sang the title role of Puccini's last opera, Turandot,

at the Vienna State Opera in 1983. It became a role with which she has

been closely identified. Since 1983, she has performed the role over

a hundred times including at the Metropolitan Opera, La Scala, Arena di

Verona, San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Washington Opera,

Opera Company of Boston under Sarah Caldwell (in

1983), Barcelona, and Houston Grand Opera. She has also portrayed Turandot

in six television and video productions, including a Vienna State Opera

production directed by Harold

Prince, a Metropolitan Opera production created by Franco Zeffirelli

production and a production designed by David Hockney filmed at the

San Francisco Opera. She also sang the role at the Aurora Opera house

in Gozo, Malta. She has recorded Turandot twice (audio CD), conducted

first by Lorin Maazel and later Roberto Abbado.

See my interviews with Paul Plishka, and Margaret Price Marton received the Persian Golden Lioness Lifetime Achievement Award in operatic music from The World Academy of Arts, Literature and Media - WAALM in 2006.

-- Names which are links in this box and throughout

this webpage refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

Eva Marton at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1979 - Andrea Chénier (Maddalena) with

Domingo, Bruson, Sharon Graham/White, Kuhlmann, Voketaitis, Gordon; Bartoletti, Gobbi, Saamaritani

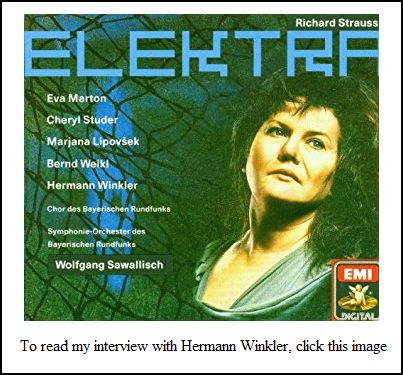

1980 - Lohengrin (Elsa) with Johns, Martin, Roar, Sotin, Monk; Janowski, Oswald (Dir & Des), Schuler (lights - for all productions listed here) [Photo of Marton as Elsa in this production with Johns interview] 1981 - Fidelio (Leonora) with Vickers, Roar, Plishka/Macurdy, Hynes, Hoback, Kavrakos/Del Carlo; Kuhn, Hotter 1982 - Tosca (Tosca) with Luchetti, Wixell/Nimsgern, Kavrakos, Tajo, Andreolli, Cook; Rudel, Gobbi, Pizzi 1984 - Frau ohne Schatten (Empress) with Johns, Nimsgern, Zschau, Dunn, Devlin; Janowski, Corsaro, Chase 1989-90 [Opening Night] - Tosca (Tosca) with Giacomini/Jóhannsson, Nimsgern, Runey, Tajo, Andreolli; Bartoletti, Gobbi/de Tomasi, Pizzi 1991-92 - Turandot (Turandot) with Bartolini, Mazzaria, Kavrakos; Bartoletti, Farlow, Hockney 1992-93 - Elektra (Elektra) with Secunde, Rysanek, Johnson, Busse; Slatkin, Friederich, Schavernoch 1993-94 - Walküre (Brünnhilde) with Morris, Jerusalem, Kiberg, Lipovšek, Hölle; Mehta, Everding, Conklin 1994-95 - Siegfried (Brünnhilde) with Jerusalem, Morris, Clark, Wlaschiha, Maultsby, Halfvarson; Mehta, Everding, Conklin 1995-96 - Götterdämmerung (Brünnhilde) with Jerusalem, Salminen, Lipovšek/Maultsby, Held, Wlaschiha; Mehta, Everding, Conklin Ring Cycle with cast as above, except Elming (Siegmund), Salminen (Hunding) |

BD: Does it disturb your technique to have that extra

blast of orchestra coming right back towards you?

BD: Does it disturb your technique to have that extra

blast of orchestra coming right back towards you?  BD: How do you decide which roles

you will sing, and which you will skip?

BD: How do you decide which roles

you will sing, and which you will skip?  BD: How do the different maestri

affect your performance?

BD: How do the different maestri

affect your performance?  BD: So is it evil turned inwards?

BD: So is it evil turned inwards? EM: It’s a necessary, inexpensive

solution. It’s a much better solution than being home and

listening to a recording. It can be very interesting and you

can really be captured by it, and there is the unexpected in a concert

performance because it will never be the same. When you can listen

to a recording many times, and it’s always the same, but in a live performance,

either in the theater or in the concert, there’s always something new.

There are the vibes that go from the singer to the audience that you

don’t get in the recording. If I should cry and the audience

cries with me, then that’s wonderful, and that’s theater.

EM: It’s a necessary, inexpensive

solution. It’s a much better solution than being home and

listening to a recording. It can be very interesting and you

can really be captured by it, and there is the unexpected in a concert

performance because it will never be the same. When you can listen

to a recording many times, and it’s always the same, but in a live performance,

either in the theater or in the concert, there’s always something new.

There are the vibes that go from the singer to the audience that you

don’t get in the recording. If I should cry and the audience

cries with me, then that’s wonderful, and that’s theater.A little over nine years later, in January of 1992, we met again, this time at her hotel. We had set up the appointment on the phone, and when I arrived she told me, “You have a very good voice! When I heard you on the phone, I thought, as we say in Germany, he is ein Geborener, he is born for this job, to be vocal! The voice is very positive, how you speak.” I thanked her for the lovely compliment, and after a bit more chit-chat, I mentioned that the Chicago area had quite a large group who were originally from Hungary. That is where we pick up the conversation . . . . .

EM: I’ve never met them. They’re

not coming to me. I have just two or three people here around

me. The others don’t seem to be comfortable enough to come

to me. Maybe my name is too big. That’s always my problem.

I lose many friends because of that.

EM: I’ve never met them. They’re

not coming to me. I have just two or three people here around

me. The others don’t seem to be comfortable enough to come

to me. Maybe my name is too big. That’s always my problem.

I lose many friends because of that. BD: Putting more drama into it?

BD: Putting more drama into it? [From a review by Peter G.

Davis in New York Magazine of the Nathaniel Merrill production

of Frau ohne Schatten at the Met, which opened October 12, 1981,

conducted by Erich

Leinsdorf, and was dedicated to the memory of Karl Böhm.]The surprise of the evening was Eva Marton

as the Empress. Her stratospheric role has been the property of the

indestructible Leonie Rysanek for the past quarter century, but Marton

gave no one cause to regret the substitution. In contrast to the Dyer's

Wife, the dignified Empress expresses her agonizing dilemma in purely

vocal terms, a tortured lyricism at a pitch of fevered intensity. It

is essentially a stand-and-deliver role, and while Marton's measured

singing may have seemed a trifle placid compared to Rysanek's whiplash

phrasing, the Hungarian soprano unflinchingly rose to every challenge,

often with thrilling results. She hurled forth one ravishingly beautiful

note after another with incomparable power, security, and total sheen,

capping it all with a stunning high D-flat in her dream sequence. At

the end, Nilsson received the respect due an old favorite, but Marton

was greeted with the tumultuous approval of an audience that had unexpectedly

discovered a star. |

BD: Who will be singing the Kaiser? [It would

be Thomas Moser.]

BD: Who will be singing the Kaiser? [It would

be Thomas Moser.]

BD: He was just here a few weeks ago with the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra.

BD: He was just here a few weeks ago with the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra. EM: The first time I did Brünnhilde

was in ’84 in San Francisco. It was a Nikolaus Lehnhoff production,

and Edo de Waart was the conductor. It was a very, very new old-fashioned

Ring. We played it very, very modern on the stage.

The stage was beautiful, with the old tradition going with the new tradition

in another way. I think that it’s the real opera theater.

I sang the first time in Siegfried. I couldn’t do Die

Walküre, and I thought maybe it would be better if they not think

how about the Siegfried wakes up with a new woman, not what she was

in Die Walküre. The next year I did Götterdämmerung

and Siegfried together. Lehnhoff was more of a father to

me in both. He took my hand and he led me over the difficulties.

It’s very interesting just to learn, step by step, about Brünnhilde

more and more. It’s a work that is living, about what is left

of life. It’s just a good base, and I didn’t do so many performances.

I waited always for big opera houses and big things. I did Die

Walküre in Ghent, and then I waited. I had a possibility

to do it, but life is sometimes very strange. You have a contract,

you have everything ready, but then it comes to nothing. So, I didn’t

do Brünnhilde again. But now, here in Chicago, I will be

in a new production, a new idea as a new life has begun again. Let

me see what will happen here. I think we will go on in a very modern

way. What I did as Brünnhilde was for me a big experiment.

I remember, in ’85 I wrote to my girlfriend in San Francisco, “Now

I know what is life! I can die in every moment, and every year

now.” Now it is ’92, and I don’t like to

die! [Both laugh] I know I can experiment with what to do with

this Brünnhilde.

EM: The first time I did Brünnhilde

was in ’84 in San Francisco. It was a Nikolaus Lehnhoff production,

and Edo de Waart was the conductor. It was a very, very new old-fashioned

Ring. We played it very, very modern on the stage.

The stage was beautiful, with the old tradition going with the new tradition

in another way. I think that it’s the real opera theater.

I sang the first time in Siegfried. I couldn’t do Die

Walküre, and I thought maybe it would be better if they not think

how about the Siegfried wakes up with a new woman, not what she was

in Die Walküre. The next year I did Götterdämmerung

and Siegfried together. Lehnhoff was more of a father to

me in both. He took my hand and he led me over the difficulties.

It’s very interesting just to learn, step by step, about Brünnhilde

more and more. It’s a work that is living, about what is left

of life. It’s just a good base, and I didn’t do so many performances.

I waited always for big opera houses and big things. I did Die

Walküre in Ghent, and then I waited. I had a possibility

to do it, but life is sometimes very strange. You have a contract,

you have everything ready, but then it comes to nothing. So, I didn’t

do Brünnhilde again. But now, here in Chicago, I will be

in a new production, a new idea as a new life has begun again. Let

me see what will happen here. I think we will go on in a very modern

way. What I did as Brünnhilde was for me a big experiment.

I remember, in ’85 I wrote to my girlfriend in San Francisco, “Now

I know what is life! I can die in every moment, and every year

now.” Now it is ’92, and I don’t like to

die! [Both laugh] I know I can experiment with what to do with

this Brünnhilde.

© 1982 & 1992 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in Chicago on October 28, 1982, and January 23, 1992. The first interview was transcribed and published in Wagner News in November, 1984. Portions of the second interview were broadcast on WNIB in 1992, 1993, 1996, 1998, and 1999. This transcription was made in 2018, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.