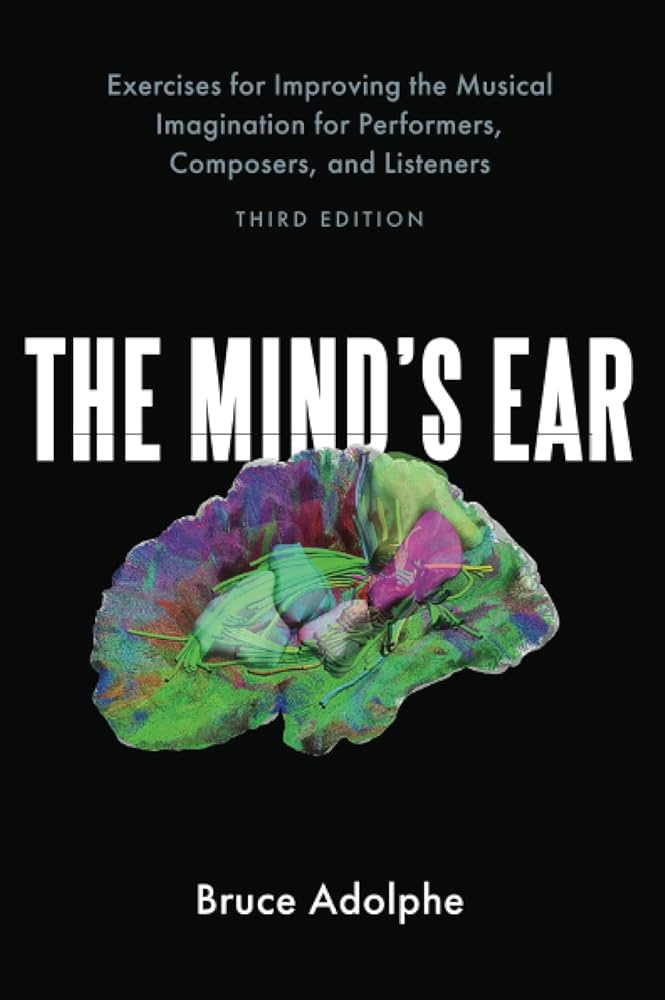

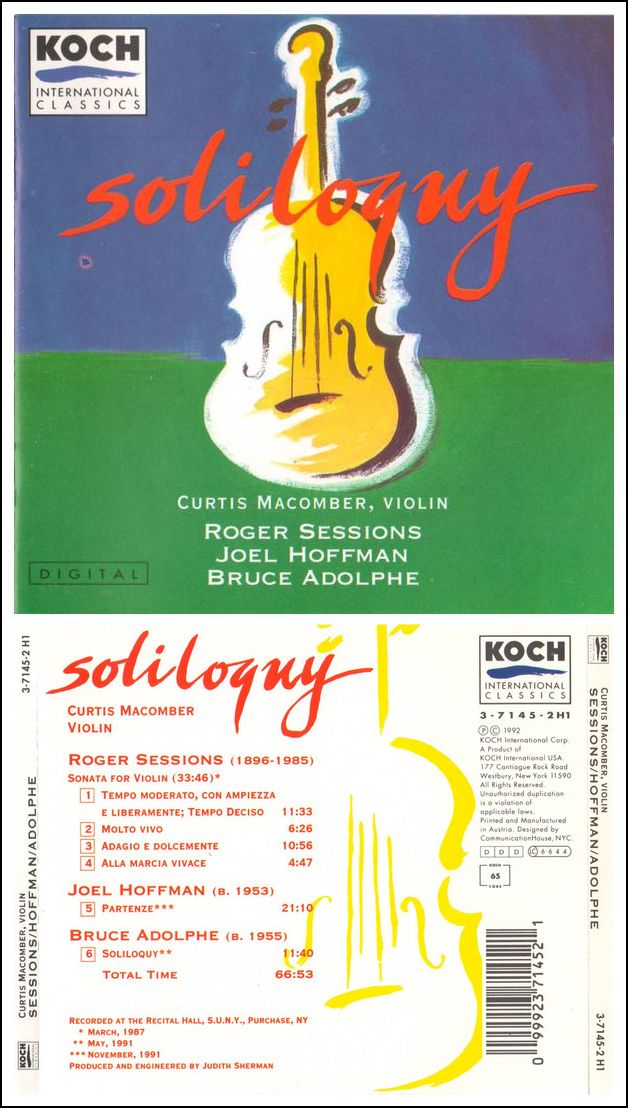

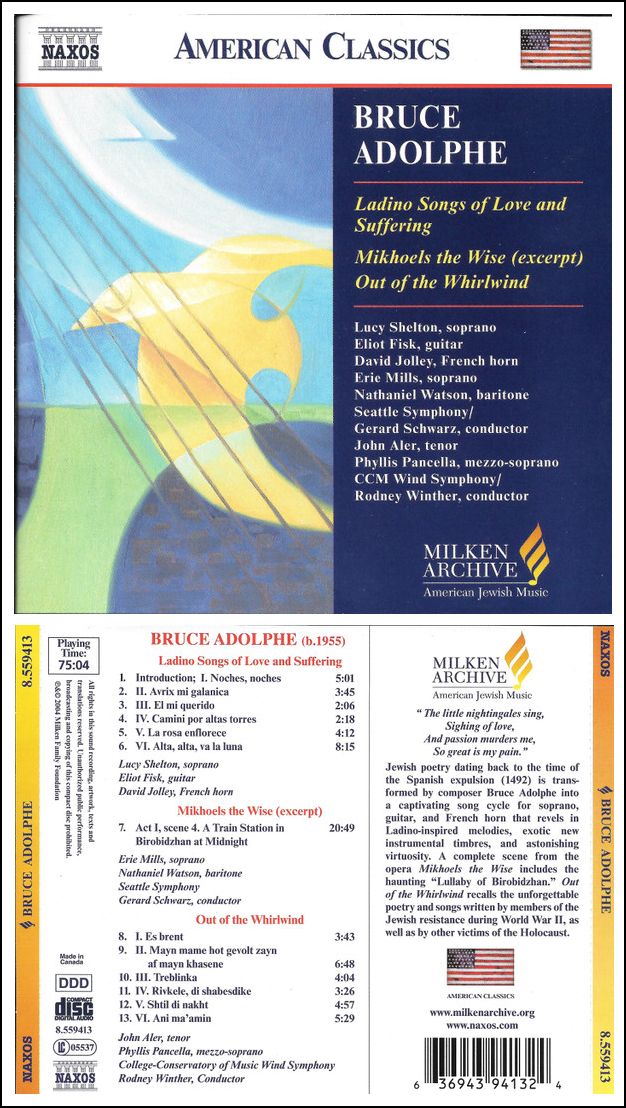

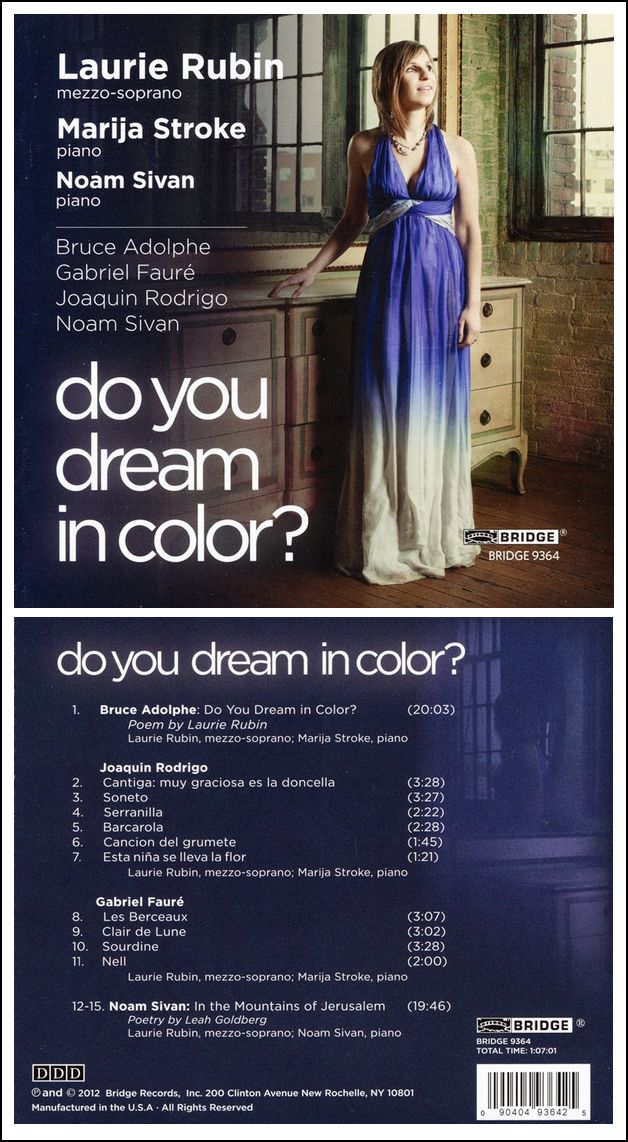

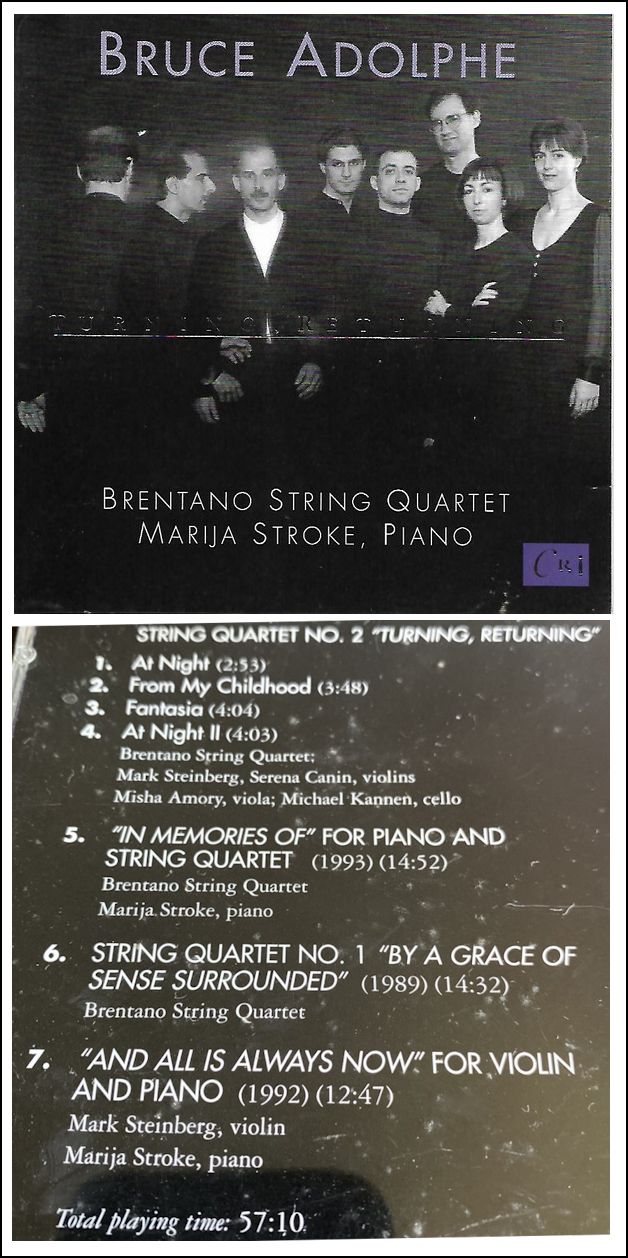

| Bruce Adolphe (born May 31, 1955) is a composer,

music scholar, the author of several books on music, and pianist. He is

currently Resident Lecturer and Director of Family Concerts of the Chamber

Music Society of Lincoln Center, where he has been a key figure since 1992.

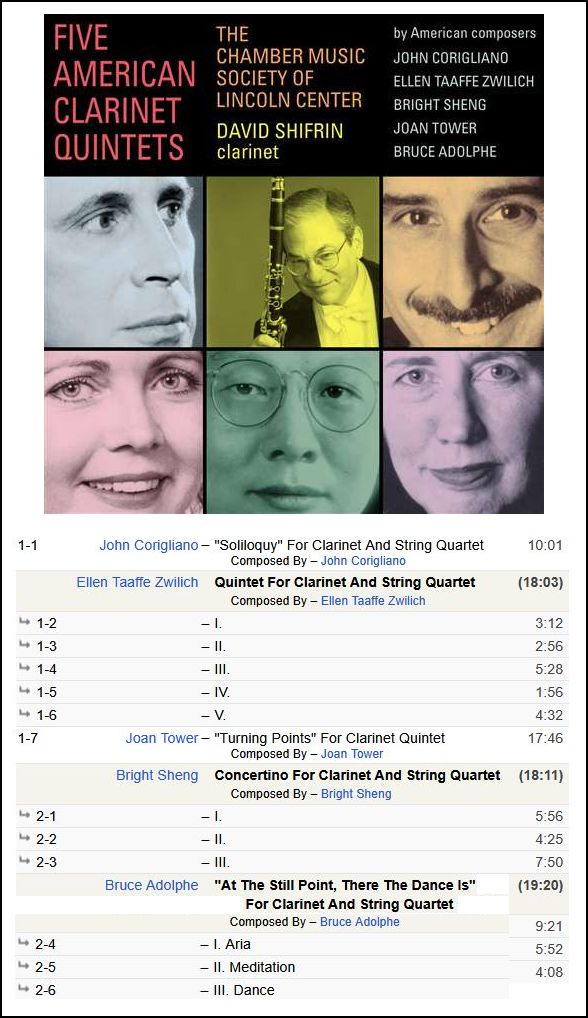

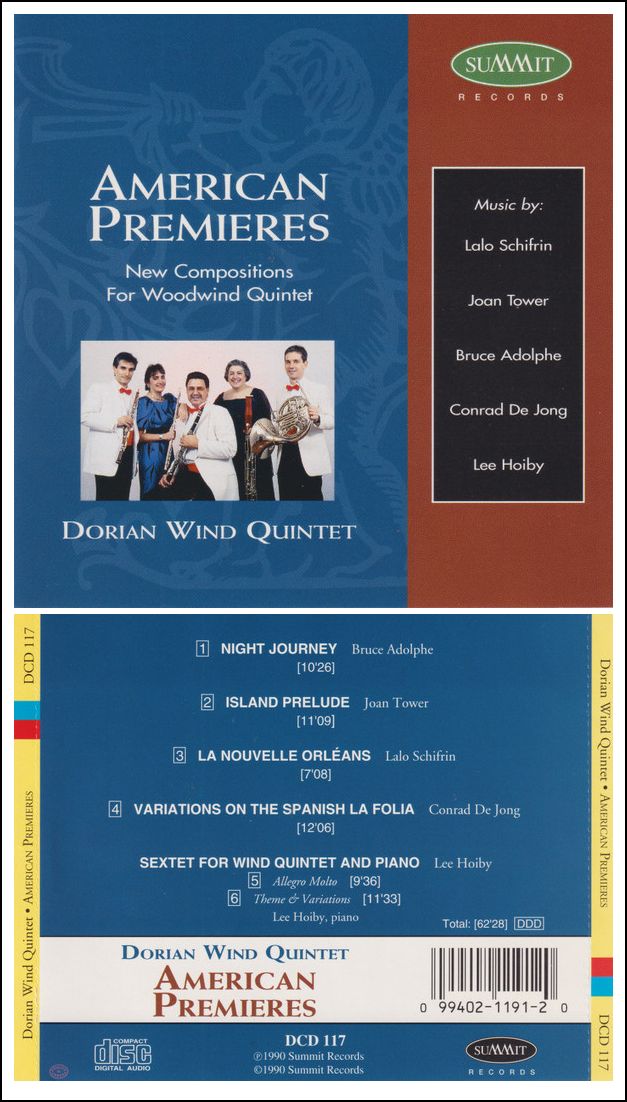

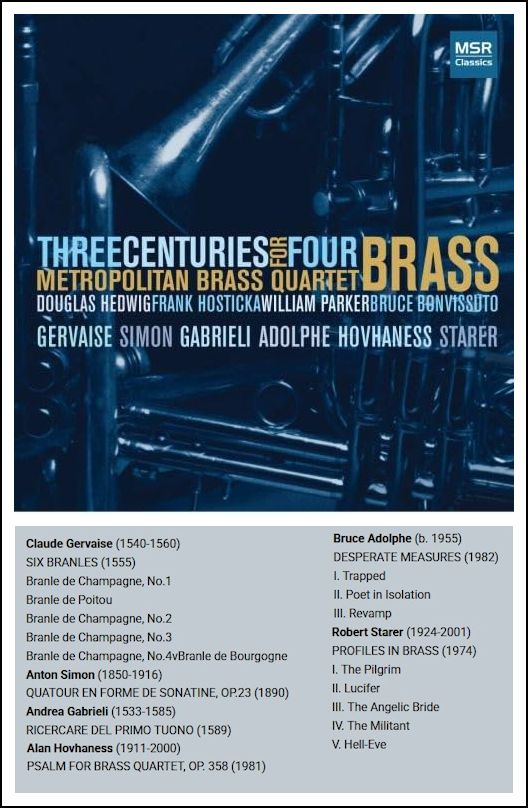

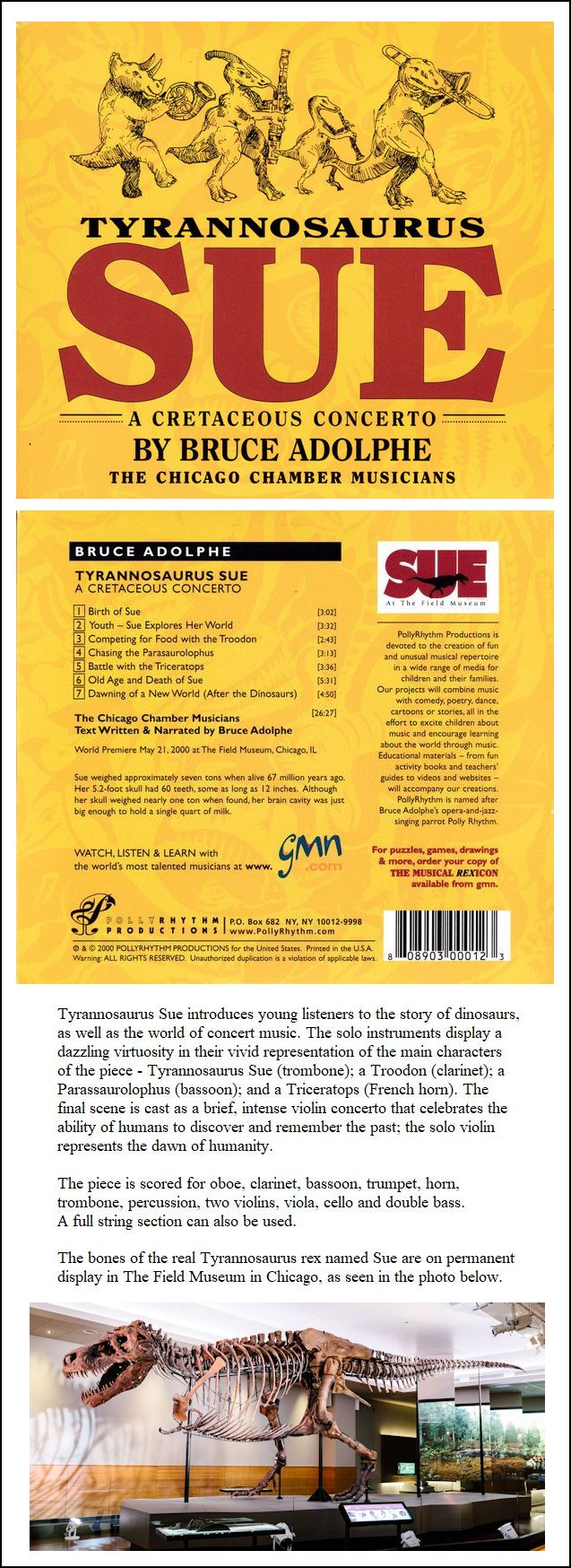

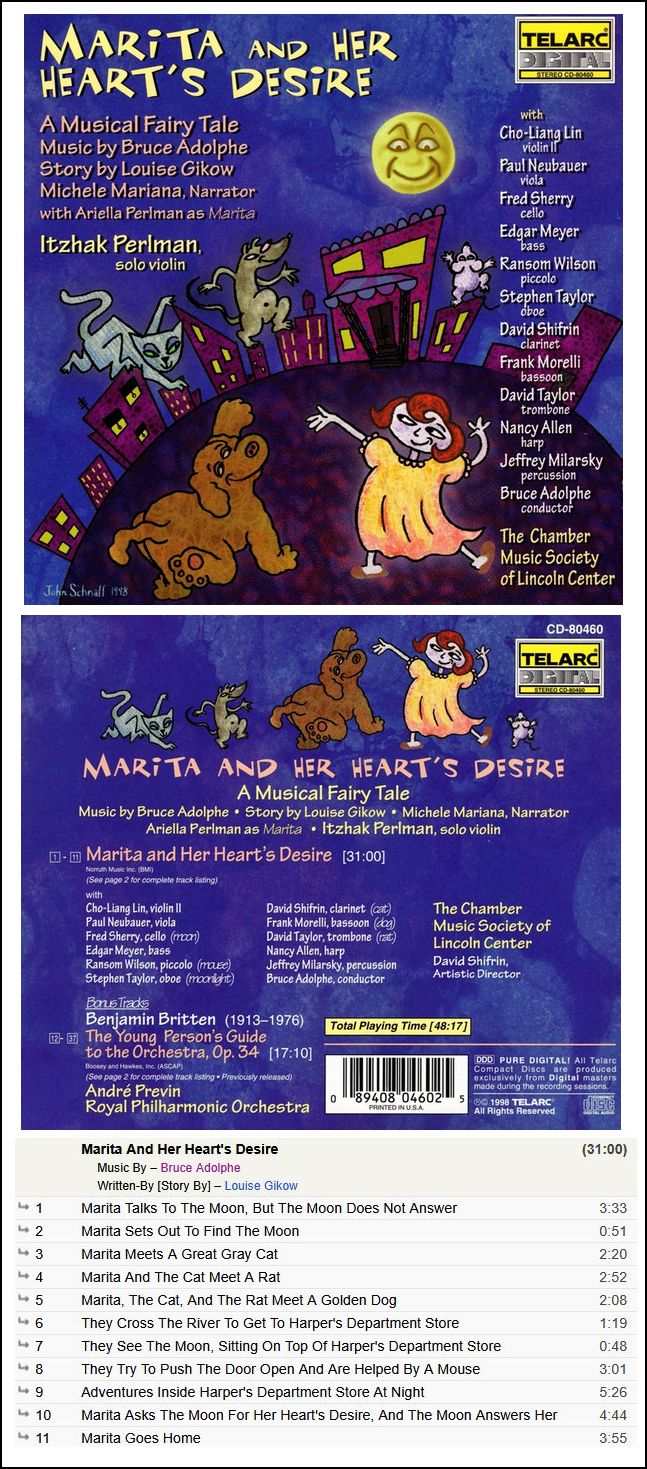

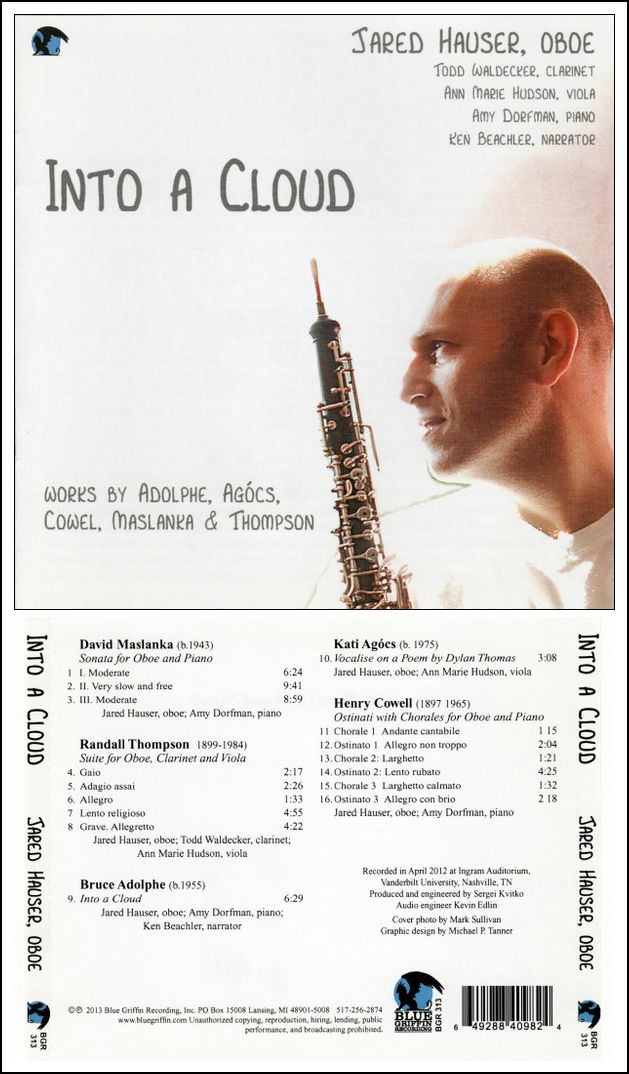

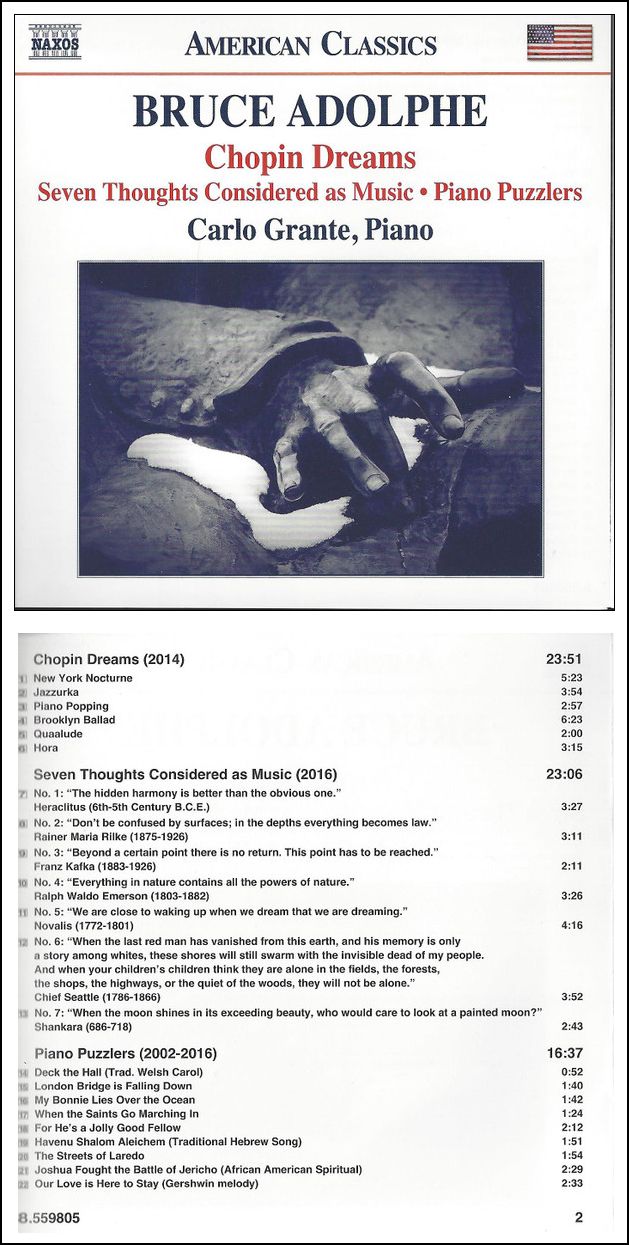

He earned a Bachelor of Music and a Master's of Music from Juilliard in 1976. Adolphe has composed music for Yo-Yo Ma, Itzhak Perlman, Joshua Bell, Daniel Hope, Carlo Grante, Sylvia McNair, the Beaux Arts Trio, the Brentano String Quartet, the Miami Quartet, the National Symphony Orchestra, the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, the Chicago Chamber Musicians, the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, and many other performers and organizations. In 2009, an evening of Adolphe's chamber music was presented at The Kennedy Center. Adolphe is also known for his compositions for young listeners. These works are created primarily for The Learning Maestros, Adolphe's education company, which he co-founded with Julian Fifer, an impresario best known as founder and executive director of the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra. His compositions for young listeners are often interdisciplinary, combining music with science, literature, history, visual arts, and current events. Many more details of his output are available on his official website. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

The American choral conductor, Amy Kaiser, was a Fulbright

Fellow at Oxford University. She holds a degree in musicology from

Columbia University. A graduate of Smith College, she was awarded the

Smith College Medal for outstanding professional achievement.

The American choral conductor, Amy Kaiser, was a Fulbright

Fellow at Oxford University. She holds a degree in musicology from

Columbia University. A graduate of Smith College, she was awarded the

Smith College Medal for outstanding professional achievement.Director of the St. Louis Symphony Chorus since 1995, Amy Kaiser is one of the country’s leading choral directors. She has conducted the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra in George Frideric Handel’s Messiah, Schubert’s Mass in E flat, Antonio Vivaldi’s Gloria, and sacred works by Haydn and W.A. Mozart, as well as Young People’s Concerts. Guest conductor for the Berkshire Choral Festival in Massachusetts, Santa Fe and at Canterbury Cathedral and Music Director of the Dessoff Choirs in New York for 12 seasons (1983-1995), she led many performances of major works at Lincoln Center. Other conducting engagements include Chicago’s Grant Park Music Festival, Peter Schickele’s PDQ Bach with the New Jersey Symphony, and more than 50 performances with the Metropolitan Opera Guild. Principal Conductor of the New York Chamber Symphony’s School Concert Series for seven seasons, Amy Kaiser also led Jewish Operas and many programs for the 92nd Street Y’s acclaimed Schubertiade. She has prepared choruses for the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Ravinia Festival, Mostly Mozart Festival, and Opera Orchestra of New York. Amy Kaiser is a regular pre-concert speaker for the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra and presents popular classes for the Symphony Lecture Series and Opera Theatre of St. Louis. A former faculty member at Manhattan School of Music and The Mannes College of Music. |

© 1990 & 2000 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in Chicago on August 9, 1990, and May 17. 2000. Portions were broadcast on WNIB 1995 and in 2000. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.