|

[By way of introduction, the following text

was taken from the artist's website in September, 2023. The CD cover photo

with André Previn

is from another source. Note that links on this webpage refer to my interviews

elsewhere on my website. BD]

------------------

OK, so, now what?

35 years. What?!? The Performance History document and the Discography show plenty of evidence I spent more than 35 years making my living as a singer. Most of those 35 years were spent working at the very highest level of the classical music business: the Metropolitan Opera, the New York Philharmonic, the Chicago Symphony – at Ravinia and on Michigan Avenue, the Salzburg Festival and the Philharmonics of Vienna and Berlin. Those were regular stops every season. I still have a 5,000 Austrian Schilling note in my desk drawer from the days before the Euro. Yes, there were days before the Euro.

There were also life-changing experiences at Opera Theater of St. Louis, the Indianapolis Symphony, the Atlanta Symphony, and Carnegie Hall. I sang at Carnegie Hall a lot. It was all before social media, though, so no one knew. I got to sing a recital at the Supreme Court, by special invitation from Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, and I got to sing with the Vienna Philharmonic at the Vatican for Pope John Paul II’s 80thbirthday, which I thought was just grand.

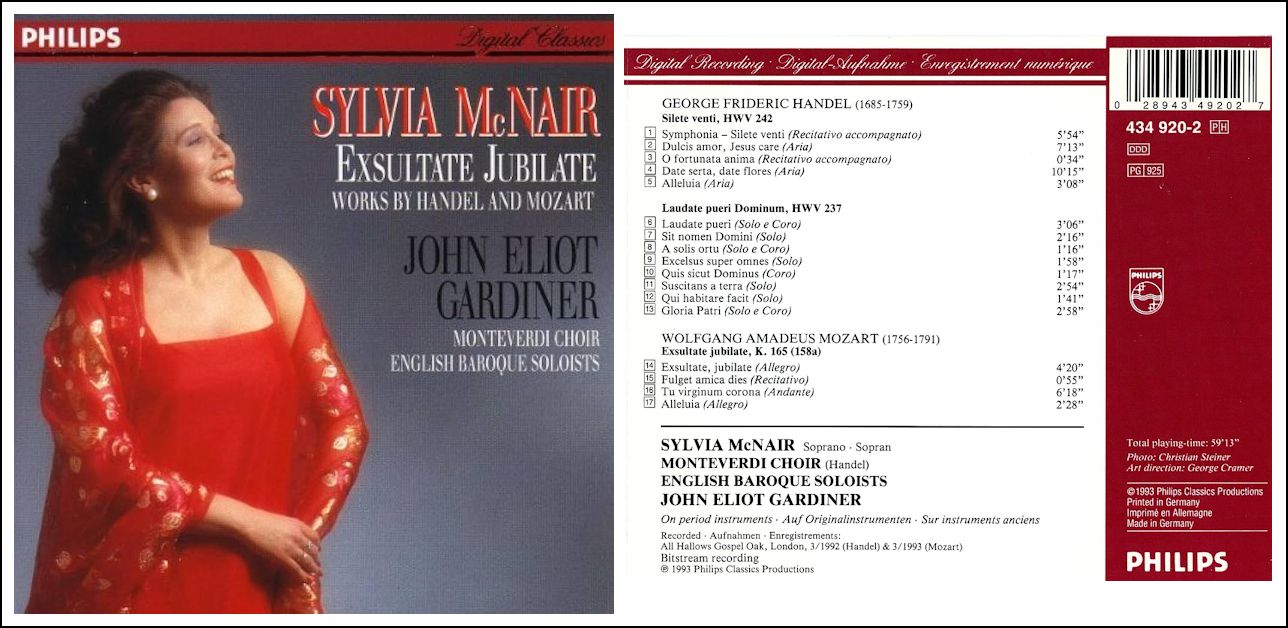

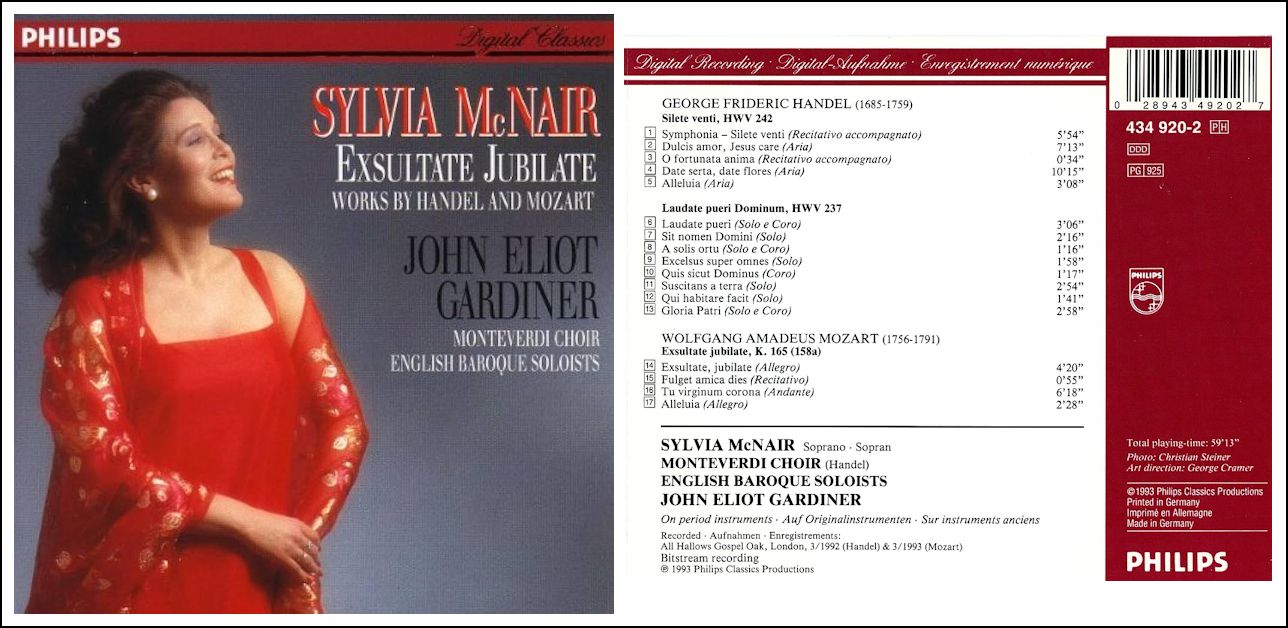

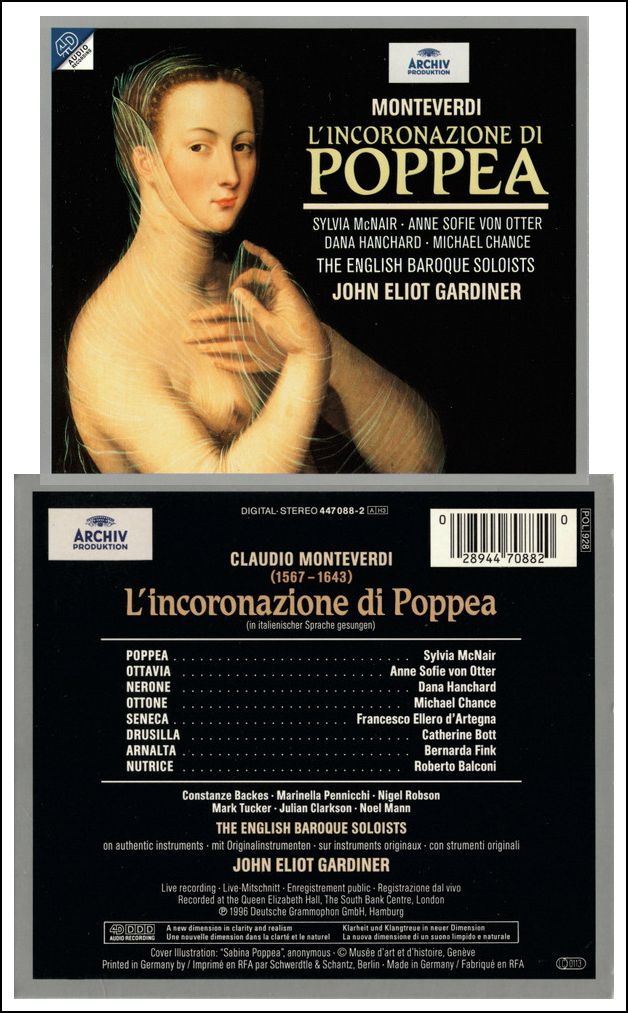

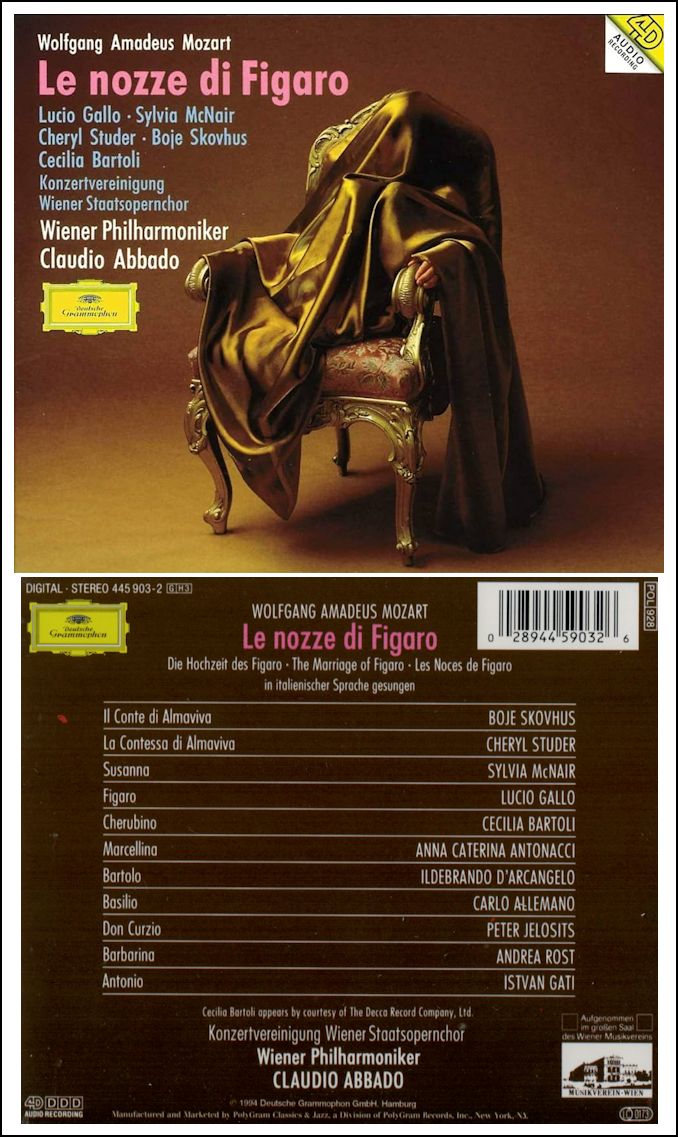

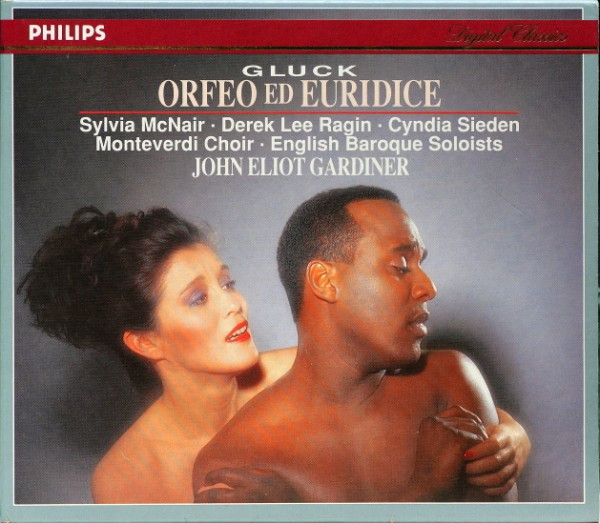

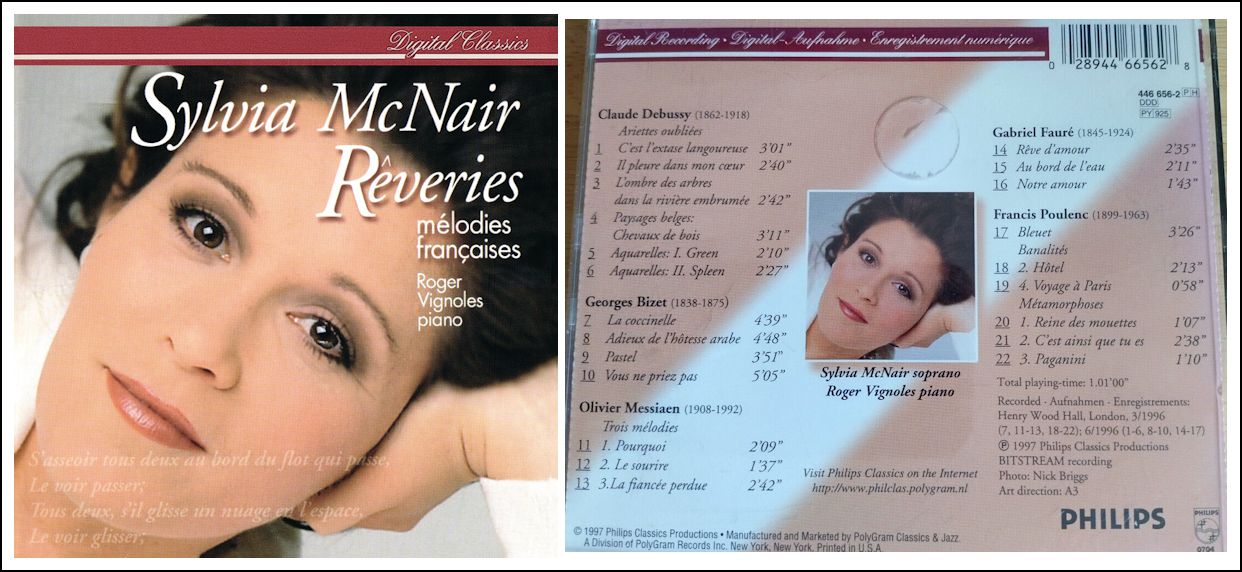

Riding the wave of the CD boom, I made a lot of recordings in the 1980s and ‘90s. Over 70, actually. Works by Bach, Handel, Mozart (lots of Mozart), Beethoven, Brahms and Mahler. I was nominated for the Grammy award five times and won twice! Those two Grammys are on a shelf in my home but you have to hunt for them.

I might also have won a Grand Prix du Disque but I’m not sure. I don’t speak French.

After roaming the classical music world for 20 years, I made a bold – some might say stupid – decision. I chose to walk away from all of it to spend more time singing songs I love from the American Songbook. That would be the Great American Songbook, songs by Gershwin, Porter, Bernstein and Sondheim, which really are Great. I also did musical theater productions, cabaret shows and a few jazz projects. It just felt more authentic, it felt comfortable and I loved it! My standard quote became: “Doing music I love, with people I love, in places I love; for me life does not get any better”.

In 2006, I joined a faculty. As Mrs. Anna (from ‘The King & I’) famously said: “By my students I am taught”. Those words certainly describe my experience as a teacher. To touch the lives of students, or any young person, is to touch the future. I have a lot packed into my head and heart from 35 years of professional experience. Sharing it gives it meaning beyond compare. But, truth to tell, most of the learning was actually done by me.

However, like it or not (and I do both, depending on the day) That Was Then and This Is Now.

Today, I am fully retired and wondering why I waited until my early-60s to do that! I am inventing a retirement career teaching ENL (formerly known as ESL) and adult literacy through a program at my local library called VITAL, Volunteers In Tutoring Adult Learners. I often feel this is the most important work of my life. Helping international folks understand and speak English with more confidence and humor is a great joy!

I've also begun volunteering with the Mobile Food Pantry, part of the Area 10 Agency on Aging's outreach in my community.

Many hours every week, I work for the Refugee Support Network in Bloomington. I'm on the Board and I head-up the Special Friends. Our clients are some of the bravest people I've ever met and it is an honor to work alongside them.

I’m also a classical-music deejay on WFIU, the NPR affiliate at Indiana University. It’s a part-time gig where I work with young, smart, funny people. I’m hoping they make me smart and funny, too. Besides, with them I always have Tech Help. I still sing occasionally for my beloved Causes (please do visit that page of this website) and for ‘friends & family’ events. So far, no one has run to get the hook.

Mahatma Gandhi said, “LIVE as though you’ll die tomorrow. LEARN as though you’ll live forever”. So I continue to attend lectures, take copious notes, and learn as much as I can. Whether it's hearing a NASA scientist talk about the ISS or a pediatrician discussing the Flint, MI, water crisis or learning about the U.S. Constitution so I can half-way explain the First and Second Amendments to my ENL conversation group, I adore learning new things! I’ve also joined a 20-voice ‘a cappella’ choir called Voces Novae where I sing in the No Stress section, also known as Alto II. Let the youngsters worry about high notes, been there, done that …

Other than those retirement career activities, I exercise, do yoga, travel, read, Netflix binge and enjoy my awesome circle of friends! Living the Dream. I’m healthy, I’m comfortable, I’m happy. Who could ask for anything more?

|

Sylvia McNair with Lyric Opera of Chicago

October/November, 1995 - The Ghosts of Versailles [Corigliano] (Rosina) with Hagegård, Dwayne Croft, Wendy White, Greenawald, Clark; Slatkin, Colin Graham, Conklin, Schuler, Tallchief, Palumbo, Dufford * * *

* *

Sylvia McNair with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra At Orchestra Hall October 6, 1990 [Centennial Gala] - Beethoven Symphony #9 (Fourth Movement), with Susanne Mentzer, Gary Lakes, Samuel Ramey; Chicago Symphony Chorus, Margaret Hillis; Sir Georg Solti

To launch the Chicago Symphony Orchestra's

100th season, an all-star

cast of conductors and soloists was assembled for a gala opening concert on October 6, 1990. Left to right, back row: Associate Conductor Kenneth Jean, pianist András Schiff, conductor Lorin Maazel, tenor Gary Lakes, soprano Sylvia McNair, bass Samuel Ramey; middle row: Music Director Designate Daniel Barenboim, Lady Valerie Solti, Music Director Sir Georg Solti, conductor Leonard Slatkin, cellist Yo-Yo Ma; front row: violinist Isaac Stern, cellist/conductor Mstislav Rostropovich, mezzo-soprano Susanne Mentzer, pianist/conductor Murray Perahia. October 20, 21, 22, 25, 1994 - Mozart aria K. 369, and Mahler Symphony #4 conducted by Michiyoshi Inoue December 31, 1996 - Works by Bernstein, Gershwin, Herbert, Kern, Loewe, Rodger, and Johann Strauss, Jr, conducted by David Alan Miller January 16, 17, 18, 21, 1997 - Mahler Symphony #2 [Resurrection], wth Markella Hatziano, conducted by Bernard Haitink December 31, 1998 - Works by Gershwin and Johann Strauss, Jr., conducted by David Alan Miller At the Ravinia Festival July 4, 2003 - Works by Gershwin, conducted by David Alan Miller July 23, 2011 - Works by Gershwin, with Brian Stokes Mitchell, conducted by David Alan Miller July 26, 2015 - Works by Hamlisch, with Maria Friedman and Jeremy Hays, conducted by David Alan Miller August 26, 2016 - Works by Porter, with Kela Blackhurst and Ryan VanDenBoom, conducted by David Alan Miller August 13, 2017 - Works by Gershwin, with Leslie Kritzer and Ryan VanDenBoom, conducted by Emil de Cou |

© 1995 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 19, 1995. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1998. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.